SEDE VACANTE 1417

July 4, 1415 — November 11, 1417

Deposition of Popes

The Council of Constance [ above ] opened on November 5, 1414. Its goals were: to reform the Church, and to end the Great Schism. It was Sigismund, King of the Romans, who induced Pope John XXIII to summon the Council. Pope John had made it his business to destroy King Ladislaus of Naples, who had been the protector of Pope Gregory XII, but it was Ladislaus who drove John out of Rome and into the hands of King Sigismund (See Finke, Acta, 88-107).

By a decree of February 7, 1415, the Fathers of the Council of Constance changed the method by which votes were being cast. Up to that point, each member of the Council cast his vote in each Session—a practice which gave continuous numerical superiority to the Italians and gave John XXIII every expectation of being able to manage the Council to his satisfaction. But the new method of voting was to be by "nations", which considerably reduced the power of the Italians. Pope John XXIII was deposed by the Council of Constance on May 29, 1415 (Gieseler IV, p. 297 n. 9). Gregory XII resigned on July 4, 1415, and was appointed Cardinal Bishop of Porto and Legate of the Marches by the Council (Gieseler IV, p. 298 n.10). The Spanish governments renounced the last surviving Antipope, "Benedict XIII" (Pedro de Luna, elected unanimously by the Avignon cardinals in 1394), on January 6, 1416 (Gieseler IV, 298 n. 11). This Benedict died in 1423. The Council of Constance itself dissolved on April 22, 1418.

Two weeks after the death of the former Pope Gregory XII (Cardinal Angelo Correr, Bishop of Porto) at Recanati near Ancona, on October 18, 1417, Cardinal Pietro Stefaneschi also died (Panvinio, Epitome, p. 294). Born in the Trastevere, he was a Cardinal of the Roman Obedience, appointed by Innocent VII (Cosimo Gentile de' Migliorati) on June 12, 1405 (Cardella II, 330-332). He was assigned the Deaconry of S. Angelo in Pescheria. Stefaneschi participated in the election of Pope Gregory XII (Angelo Correr) in 1406, and was made his Vicar in Rome when the Pope was forced to leave the city because of the behavior of Paolo Orsini (Gregorovius VI. 2, p. 590). But he attended the Council of Pisa, which deposed both Benedict XIII (Pedro de Luna) of the Avignon Obedience and Pope Gregory XII of the Roman Obedience on June 5, 1409. Cardinal Stefaneschi then participated in the election of the Antipope Alexander V (Pietro Philarghi). Under "Pope Alexander", he opted for the Deaconry of S. Cosma e Damiano. In May of 1410 he participated in the election of "Pope John XXIII" (Baldassare Cossa). And he was Vicar of Rome again, as well as for the Patrimony and Umbria, for "John XXIII", and again with the Deaconry of S. Angelo.. He did not, however, attend the election that took place at the Council of Constance in November, 1417. He had died on the last day of October, 1417, during the Sede Vacante, and was buried in S. Maria in Trastevere. The hexametrical inscription on his monument reads (Forcella Inscrizione II, p. 342, no. 1048. The text given by A. Ciaconius, Vitæ, et res gestæ Pontificvm Romanorum et S. R. E. Cardinalivm II, 724), and followed by Salvador Miranda, is defective, as can be seen in the reproduction below):

CVI SVA PRO MERITIS RADIANTEM FRONTE GALERVM

CARDINEVM TRIBVIT VIRTVS ETATE VIRENTI

ASPICE CVM LACRIMIS LECTOR QVO MARMORE CLAVSVM

IMPIA MORS RAPVIT FORMAM NATVRA NITENTEM

ANGELICAM DEDERAT SAPIENS ET DOCTVS IN OMNI

PREFVIT ELOQVIO TITVLVM CVI SANCTE DEDISTI

ANGELE PETRVS ERAM NOMEN STATE LINEA PRIMA

DE STEPHANESCIS MATERNO CARDINE NATVS

FVLSIT AB HANIBALE TAM LONGI TRAMITI EVO

OSSA TERIT TELLVS ANIME STET GLORIA CELO.

+ OBIT ANNO.DNI .M.CCCC.XVII.MENSIS.OCTVBER A DI

VLTIMO . MAGISTER PAVLVS FECIT HOC OPVS.

The Electors

The composition of the electoral body of the Conclave of 1417 was unique. Andreas von Regensburg (p. 140 Leidinger) states:

...reductis tribus obedienciis in unam, ut premissum est, decretum est a concilio ut ad eleccionem futuri summi pontificis ad cetum cardinalium, qui numero erant 23, de nacionibus, que numero erant 5, scilicet italica, gallicana, germanica, anglicana et hyspanica, iungerentur viri docti experti et a nacionibus electi numero 30, hoc est de qualibet nacione numero 6, qui unacum cardinalibus haberent auctoritatem tocius concilii eligendi papam....

The same information is provided by Pope Martin V (Odo Colonna) himself in his electoral manifesto, Summus Omnium Creator , December 3, 1417 (Rymer, Foedera 9, 523-524; 535-537; Lenfant II, 185-187):

Quibus, triginta numero, per ipsas nationes electis, et per idem Sacrum Concilium praefatis Cardinalibus cum praedicta potestate adjunctis, die lunae, octava Novembris proximo praeterita ciricter horam quartam post meridiem, in Illius Nomine, qui perpetua mundum ratione gubernat, Cardinales numero viginti tres et adjuncti, hujusmodi cooperante Spiritus Sancti gratia, decretum et ordinatum ad hoc conclave, libertate atque securitate celeberrima ab extra custodia munitissimum, ad pacem praefatae Ecclesiae aspirantes, intrarunt.

The electoral body included twenty-three out of thirty-four persons who might be called a Cardinal, whether appointed by a Pope or an Antipope. To these were added six prelates from each of the five "nations" into which the Council was organized: Germany, Spain. England, France, and Italy. There were, therefore, fifty-three voting members at the Election. (Eubel Hierarchia Catholica I second edition, p. 34, note 7; Baronius-Theiner 27, p. 460, from the Acta of the Council). J. D. Mansi (Sacrorum Conciliorum 27, columns 1169-1170) gives the text of the Conciliar Decree "Decretum de electoribus Romani Pontificis", issued at the 41st session of the Council on Monday, November 8, 1417, which contains the complete list of Cardinals and of the 'nations'. A list of the Cardinals who took part in the Council of Constance is given in Hermann von der Hardt (Tomus 5, pars 2, cols. 11-12; Tomus 6, pars 2, cols. 21-22). A list of the Electors is given by Onuphrio Panvinio (Epitome, 287-290). Baluzius (Miscellaneorum Liber Sepltimus, 90-97) prints a treatise called "Narratio de forma et modo electionis factae de Domino nostro Papa Martino V. in Concilio Constantiense", in which is contained (pp. 91-92) a list of the electors. Von der Hardt prints several lists of the electors in Volume IV, Pars XII (columns 1471-1474; 1479-1480). Fifteen cardinals were Italian, seven were French, one was Spanish.

A list of the English adjuncti electores is given by Thomas Walsingham, monk of St. Albans, in his Historia Anglicana (Volume II ed. H. T. Riley, p. 319): "unde de Anglia ingressi sunt Conclave Episcopi Londiniensis, Bathoniensis, Norwicensis, Lichefeld, Abbas Eboracum et Magister Thomas de Poltone, Decanus Eboracum." See also, Von den Hardt IV, 15-17. King Henry V had announced on July 20, 1416 [Rymer, Foedera 9, pp. 370-371], that he had appointed Nicholas (Bubwyth) of Bath and Wells and Robert (Hallum) of Salisbury as his ambassadors to the General Council; they were to be associated with Richard (Clifford) of London, John (Catterick) of Coventry & Lichfield, John (Wakering) of Norwich, as well as Thomas Polton, Dean of York, William Abbot of Bury and John Prior of Worcester. Bishop John Wakering had already been given permission on July 6, to travel versus partes transmarinas pro diversis causis et negotiis, utilitatem et commodum Regis et Regni Regis tangentibus [Rymer, Foedera 9, p. 369]. It is clear that the English representatives at Constance were the choices of the King of England. These arrangements were made while Emperor Sigismund was still in England, negotiating the treaty of Canterbury. In January, 1416, King Henry also sent a special agent to observe the proceedings in Constance, Magister Robert Appilton, a cleric of York [Rymer, Foedera 9, 342].

The list of the electors for Hispania is given by Geronimo Zurita (p. 131): "Por el de Aragon, fue eligido el Maestro Felipe Malla, muy famoso Dotor en la sagrada Teologia: y por el Rey de Castilla, dõ Diego de Añaya, Obispo de Quenca, q(ue) era uno de sus Embaxadores: y por el Rey de Portugal, el Dotor Blasco Hernandez: y por el Rey de Navarra, el Obispo de Ax: y por que avian de ser seis de cada nacion, el nombrameiento de los otros dos se remitio a los votos de la misma nacion: y mediate juramento cada uno dio su voto al mas digno; y fuero nõbrados el Obispo de Badajoz, y Gonçalo Garcia de Sta Maria, que era Castellano de nacion, comi dicho es, y muy famoso Letrado, y uno de los Embaxadores del Rey de Aragon."

- Joannes de Bronhiaco (Jean Allarmet de Brogny), Savoyard, Suburbicarian Bishop of Ostia and Velletri, Dean of the Sacred College of Cardinals. Vice-Chancellor (a cardinal of Clement VII). (died 1426) [Cardella II, 355-359]. "Vivariensis"

- Angelo d'Anna de Sommariva, OCam., Suburbicarian Bishop of Palestrina (a cardinal of Urban VI) [Eubel I, 25] (died July 21, 1428).

- Petrus Fernandi de Frigidis (Pedro Fernández de Frías), Spanish, Suburbicarian Bishop of Sabina (a cardinal of Clement VII) [Cardella II, 359-360; Eubel I, 29]. Archpriest of the Vatican Basilica (1411-1420) [A. Andreucci, De vicariis Basilicarum Urbis editio altera (Romae 1854), 67; L. Martorelli, Storia del clero vaticano, p. 220]. "Oxomensis" (died September 19, 1420).

- Giordano Orsini, Suburbicarian Bishop of Albano (a cardinal of Innocent VII) (died May 29, 1438) [Eubel I, 26).

- Antonio Corarrio, Venetian, Suburbicarian Bishop of Porto e Santa Rufina, Sub-Dean of the Sacred College of Cardinals (a cardinal of Gregory XII). Nephew of Gregory XII [Cardella II, 339-341]. "The Cardinal of Bologna"

- Francesco Lando, a Venetian, Cardinal Priest of S. Croce in Gerusalemme (a cardinal of John XXIII) (died December 26, 1427) [Eubel I, 32].

- Giovanni Dominici, OP, Florentine, Cardinal Priest of S. Sisto (a cardinal of Gregory XII, and his Legate at the Council), Bishop of Ragusa. Major Penitentarius [Cardella II, 336-339; Eubel I, 31; P. Mandonnet, HJb 21 (1900), 388-402].

- Antonio Panciera, Cardinal Priest of S. Susanna (a cardinal of John XXIII), Patriarch of Aquileia (died July 3, 1431) [Eubel I, 32].

- Gabriel Condulmer, Venetian, Cardinal Priest of S. Clemente (a cardinal of Gregory XII), Bishop of Siena [Cardella II, 341-342]. Nephew of Gregory XII. "Senensis"

- Branda Castiglione, of Milan, Cardinal Priest of S. Clemente (a cardinal of John XXIII). Bishop of Piacenza. "Placentinus"

- Angelo Barbarigo, Venetian, Cardinal Priest of Ss. Marcellino e Pietro (a cardinal of Gregory XII). Bishop of Verona [Cardella II, 345-347] Nephew of Gregory XII.

- Petrus de Alliaco (Pierre d'Ailly), Cardinal Priest of S. Crisogono (a cardinal of John XXIII). Bishop of Cambrai (1396-1412). "Cameracensis" (died August 9, 1420) [Eubel I, 33] He was a Doctor of Theology and former almoner of King Charles VI of France (Jean Juvénal des Ursins, Histoire de Charles VI, p. 398 [ed. Michaud & Poujoulat])

- Tommaso Brancaccio, Neapolitan, Cardinal Priest of Ss. Giovanni e Paolo (a cardinal of John XXIII) Bishop of Tricarico (1405-1411; 1419-1427).

- Alamanno Adimari, a Florentine, Cardinal Priest of S. Eusebio (a cardinal of John XXIII) Archbishop of Pisa [Eubel I, 32] (died September 17, 1422). "Pisanus"

- Antonio de Challant, Savoyard, Cardinal Priest of S.Cecilia (a cardinal of Benedict XIII) [Eubel I, 30] (died September 4, 1418). Read the Bull of Martin V, closing the Council of Constance. [Cardella II, 352-353; Eubel I, 30] Former Chancellor of the Count of Savoy. In 1413 he had been Apostolic Legate of John XXIII in England [Twemlow, Calendar of Papal Registers 6 (1904) p. 175-181 (May 15, 1413)].

- Guillaume Fillastre (aged 69), of Le Mans, Cardinal Priest of S. Marco (a cardinal of John XXIII). "Philasterius" "Cenomanensis". Former Dean of Reims. (He died on Nuvember 6, 1428, at the age of 80, according to his tombstone in S. Crisogono: Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma 2 (1878), p. 170 no. 490).

- Simon de Cramaud, Cardinal Priest of S. Lorenzo in Lucina (a cardinal of John XXIII).

- Pierre de Foix, OFM, Cardinal Priest of S. Stefano al Monte Celio (a cardinal of John XXIII). [Eubel I, 33] (died December 13, 1464).

- Ludovico de Flisco (Fieschi), of Genoa, Cardinal Deacon of S. Adriano (a cardinal of Urban VI) [Eubel I, 25]. Legate of John XXIII (Cossa) in Bologna (1412-1413) [See: Frati, Archivio storico italiano 41 (1908) 144-151]. (died April 3, 1423).

- Rinaldo Brancaccio, Neapolitan, Cardinal Deacon of Ss. Vito e Modesto (a cardinal of Urban VI). Archpriest of the Liberian Basilica (after 1412).

- Oddone Colonna, Romanus, Protonotary Apostolic. Cardinal Deacon of S. Giorgio in Velabro (a cardinal of Innocent VII). Archpriest of the Lateran Basilica. Auditor of the Rota (Boniface IX). Legate in Umbria.

- Amedeo de Saluzzo, a Lombard, Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria Nuova (a cardinal of Clement VII).

- Lucido de' Conti, Romanus, Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Cosmedin (a cardinal of John XXIII).

GERMANIA

- Johannes von Walenrode, Archbishop of Riga (1393-1418). Bishop of Liège (1418-1419) [Eubel I, 302, 421]

- Nicolaus Tramba, Archbishop of Gniezno (1412-1422) [Eubel I, 265].

- Simon de Dominis, Bishop of Tragir (or Traú) (1403-1423) [Eubel I, 490].

- Lambert de Stipite, OClun., Prior of Belcheia, Diocese of Liège, Decretorum Doctor.

- Nicolaus von Dinkelsbühl, Canon of Cathedral of St. Stephen in Vienna. Sacrae Paginae Doctor.

- Conrad von Susato, Praepositus of St. Cyriach in Neuhausen, Worms. Sacrae Paginae Doctor.

ITALIA

- Bartolomeo de la Capra, Archbishop of Milan (1414-1433) [Eubel I, 333; Ughelli-Colet Italia Sacra 4, pp. 254-255].

- Francesco Carosius (Scondito), Bishop of Melfi (1412-1418) [Eubel I, 335; Ughelli-Colet Italia Sacra 1, p. 937].

- Enrico Scarampi, Bishop of Belluno e Feltre (1404-1440?) Nuncio of Gregory XII to Venice [Eubel I, 133; II, 103; Ughelli-Colet Italia Sacra 5, pp. 163-164]. Private secretary (a secretis) of the Emperor Sigismund.

- Giacomo del Camplo (Turco), Bishop-elect of Penne ed Atri (1415-1419), utroque iuris doctor, Bishop of Spoleto (1419-1424), Bishop of Carpentras (1424-1425) {Eubel I, 168, 395, 461; Ughelli-Colet Italia Sacra 1, p. 1149].

- Leonardo Dati, OP, Florentine, Master General of the Order of Preachers (Dominicans) (1414-1425), former Inquisitor of Bologna. He had been named Provinical of the Roman Province by Alexander V and Vicar-General of the Order by John XXIII [Massimiliano Pavan (ed.), Dizionario biografico degli italiani, vol. 33: 40–44; D. Mortier, Histoire des Maîtres généraux IV, 85-114].

- Pandulfo Malatesta, Archdeacon of Bologna (Younger brother of Carlo Malatesta, Orator of Gregory XII at Constance? John XXIII [Cossa] had once been Archdeacon of Bologna).

ANGLIA

- Richard Clifford, Bishop of London, 1407-1421 (consecrated at St. Paul's by Archbishop Thomas Arundel in 1401: Stubbs, 84; Brady I, 6-7) (died August 20, 1421).

- Nicholas Bub(be)wyth, Bishop of Bath and Wells (consecrated by Archbishop Arundel in 1406: Stubbs, 84; Brady I, 34-35; died 1424) [Eubel I, 130]. See: S. H. Cassan, Lives of the Bishops of Bath and Wells (London 1829) pp. 205-212.

- John Catterick, Bishop of Conventry & Litchfield (consecrated at Bologna by John XXIII, 1415: Stubbs, 85; Brady I, 26). Licentiate in Canon Law. As Archdeacon of Surrey in 1411, he had been an ambassador of King Henry IV in Picardy [Rymer Foedera 8, p. 680, 682], and then in France [Rymer Foedera 8, p. 695 (July 1, 1411)]. He was one of the commissioners sent to arrange a marriage between the Prince of Wales and a daughter of the Duke of Burgundy [Rymer Foedera 8, p. 699 (September 1, 1411)]. On February 12, 1412, he was granted the right by John XXIII to make a Will [Twemlow, Calendar of Entries in the Papal the Papal Registers relating to Great Britain and Ireland VII (London 1906), p. 306]. He was made Bishop of St. Davids in 1414 [Stubbs, Registrum sacrum anglicanum (second edition 1897), 85; Eubel I, 336]. On the problems that arose in his promotions, see Twemlow. p. 473 (February 13, 1415). Later he was briefly Bishop of Exeter (1419–died December 28) [Eubel I, 208, 243]. (President of the 'English Nation')

- John Wakering, Bishop of Norwich, 1416–April 9, 1425 (consecrated at St. Paul's, London by Archbishop Henry Chicheley: Stubbs, 85) [Eubel I, 371].

- Thomas Spofforth, OSB, Abbot of St. Mary's Monastery, York. On March 3, 1415, at Constanz, Pope John XXIII granted him the privilege of choosing whatever confessor he wished, who would have the powers to dispense him even from censures reserved to the pope [Twemlow, Calendar of Entries in the Papal the Papal Registers relating to Great Britain and Ireland 6, p. 499]. He was later Bishop of Hereford (1421-1448) [William Page, A History of the County of York Volume III (1974), 107-112; John Le Neve, Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae I (Oxford 1854), 465; J. A. Twemlow, Calendar of Entries in the Papal the Papal Registers relating to Great Britain and Ireland VII (London 1906), 58]. He had been an ambassador of Henry, Archbishop of York, to the Council of Pisa [Twemlow, Calendar of Papal Registers 6 (1904) p. 192 (January 10, 1411)].

- Thomas Polton, Dean of York (1416-1420), Protonotarius Apostolicus , Procurator of Henry V at the Roman Curia [Rymer 9, 447], Doctor Decretorum [Ulrich v. Richenthal, p. 186 ed. Buck]. He had previously been Archdeacon of Taunton in the Diocese of Wells [Twemlow, Calendar of Papal Registers 6 (1904), p. 173 (October 25, 1411); p. 287 (September 9, 1411)]. On his doings in 1412-1414 see Twemlow 6, p. 411 (March 23, 1414). On September 22, 1414, he was granted the Canonry of Strensale in the Cathedral of York [Twemlow 6, p. 474]. He was later Bishop of Hereford (1420-1422), Chichester (1422-1426), and then Worcester (1426–died August 23, 1433, at the Council of Basel) [Le Neve, Fasti I, 245, 464; Fasti III, 124. Brady I, 47; cf. Finke, Forschungen 224].

GALLIA

- Jean de Rochetaillée, Patriarch of Constantinople (1412-1423), Archbishop of Rouen (1423-1426) (later Cardinal Priest of San Lorenzo in Lucina, 1426-March 24, 1437) [Eubel I, 34, 207, 426].

- Guillaume de Boisratier, Archbishop of Bourges (1409-1421) doctor utriusque iuris (Bologna) Former private secretary of Charles VI of France, and former Chancellor of John, Duke of Burgundy. He carried out several legations for the King of France, including an effort in November, 1412, to arrange a peace with King Henry of England, and another in 1415. He was Chancellor of the Duchy of Bourges. In 1416 he was executor of the Testament of John, Duke of Burgundy [Eubel I, 139; Gallia christiana 2, pp. 85-87].

- Jacques de Gelu, Archbishop of Tours (1414-1426), Archbishop of Embrun (1427) [Eubel I, 233, 503] (Baronius-Theiner 27, p. 460 n., quotes the Archbishop's own words: "...in Octobri fui ego Jacobus archiepiscopus per nationem Gallicanam Concilii Constantiensis electus pro eligendo papam, una cum caeteris aliarum nationum et DD. cardinalibus..."

- Jean des Bertrandis, Bishop of Geneva (1408-1418), Archbishop of Tarentaise (1418-1432) [Eubel I, 261, 473].

- Robert de Chaudesolles, OSBClun., Abbot of Cluny (1416-1423). As Prior of Sauxillanges he had represented the previous Abbot of Cluny Raymond de Cadoène (1400-1416) at the Council of Pisa.

- Gauthier Crassi, Prior of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem of Rhodes. Doctor Decretorum [Hardt IV.xii, p. 1473].

HISPANIA (Aragon, Castile, Portugal)

- Diego de Anaya y Maldonado [Didacus Conchensis], Bishop of Cuenca (1407-1417), Bishop of Seville (1418-after 1427-his successor mentioned in 1431) [Eubel I, 201, 278; II, 165]

- Nicolás Divitis, OP, Bishop of Aquae Augustae (Dax) (1412-before 1423) courtier of Benedict XIII, Nuncio of Charles, King of Navarre, to the Council of Constance [Eubel I, 197].

- Juan de Villalón [Joannes Pacensis], Bishop of Badajoz (1415-1418) [M. Risco, España sagrada Tomo XXXVI (Madrid 1787), 51-54].

- Felipe de Medalia, Magister, Archidiaconus Penetensis in Ecclesia Barchionensi (Barcelona).

- Gonzalo Garsía [Gudisalvus Grasiae], Archdeacon of Burgos, Decretorum Doctor.

- Pedro Velasco, Doctor in utroque iure.

- Baldassare Cossa, ex-Cardinal Deacon of S. Eustachio (the deposed Boniface IX). Imprisoned by order of the Council. He was released on orders of King Sigismund, at the request of the new pope Martin V, in early 1418. Martin restored his cardinalate to him.

- Ludovicus de Barro (Louis de Bar), French, Cardinal Priest of SS. XII Apostoli (a cardinal of Benedict XIII) [Cardella II, 354-355; Eubel I, 30] (died June 23, 1430). Ciacconius insists that he was present, another of his multitudinous mistakes.

- Juan Martínez de Murillo, O.Cist., Cardinal Priest of S. Lorenzo in Damaso (a cardinal of Benedict XIII) [Eubel I, 30]

- Carlos Jordán de Urriés y Pérez Salanova, Cardinal Deacon of S. Giorgio in Velabro (a cardinal of Benedict XIII)

- Alfonso Carrillo de Albornoz, Cardinal Deacon of S. Eustachio, (a cardinal of Benedict XIII)

- Pedro Fonseca, Cardinal Deacon of S. Angelo in Pescheria, (a cardinal of Benedict XIII). He died in 1422, and was buried in the Vatican Basilica [Muentz and Frotheringham, Archivio della Società romana di storia patria 6 (1883), 68 and n. 2].

- Philip Repington, CRSA, Cardinal Priest of Ss. Nereo ed Achilleo, Bishop of Lincoln, England, (a cardinal of Gregory XII) [According to Eubel I, 31, he did not accept the Cardinalate] (died 1434)

- Pietro Morosini, Venetian, Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Cosmedin, (a cardinal of Gregory XII) [Cardella II, 350-351; Eubel I, 32] (died August 11, 1424).

- Johannes Dominici, Cardinal Priest of S. Sisto (created on May 9, 1406, by Gregory XII of the Roman Obedience), sent to Hungary and Poland as Legate of Gregory XII, commissioned on January 8, 1409 [Twemlow VI, p. 99; Eubel I, 31 n. 5]. He died on June 6 or 10, 1419 at Buda.

- Guglielmo Carbone, Cardinal Priest of S. Balbina, (a cardinal of John XXIII)

- Giacomo Isolani, Cardinal Deacon of S. Eustachio, (a cardinal of John XXIII) [He was in Rome, as John XXIII's Legate].

The case of Benedict XIII

Neither did the Antipope Pedro de Luna, ex-Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Cosmedin (the deposed Antipope Benedict XIII, living at Peñiscola in Spain) attend the election of a new pope. None of his cardinals who were still living still adhered to his cause (See Eubel I, p. 29 note 6). Nonetheless, an effort was made to bring him around to the thinking of the Fathers of the Council of Constance and procure his resignation or renunciation. A personal effort to achieve unity was made by King Sigismund (who set out for Spain on July 19, 1415) and King Ferdinand of Aragon, who left his sick-bed in order to accompany King Sigismund to Peñiscola (Andreas von Regensburg, Chronica, p. 140; see also, von der Hardt II, 484 ff.):

Item reductis duabus obedienciis in unam, sicut supra dictum est, restabat adhuc obediencia Benedicti XIII. Qui Benedictus spretis salutaribus monitis et requisicionibus et precipue regis Romanorum Sigismundi et orthodoxi regis Ferdinandi Arragonie, sub cuius dominio erat, ad quem Sigismundus rex cum ceteris oratoribus concilii Constanciensis per longa laboriosaque itinera venit invenitque eum in egritudine gravissima morti proximum. Qui tamen Fernandus rex contra valitudinem medicorumque consilia, ut ipse tanto dei et ecclesie negocio non deesset, se mari cum magno vite periculo committere non expavit, ut et ipse personaliter unacum rege Sigismundo ipsum Benedictum in Perpiniano requireret, ut, secundum quod promiserat et iuramento firmaverat, per suam cessionem de papatu pacem ecclesie daret. Dum ipse Benedictus a facie regum a Perpiniano fugeret eosque audire recusaret, obediencia sibi a predicto rege Ferdnando ceterisque regibus et principibus subtrahitur et concilio Constanciensi, quod erat de duabus obedienciis, ut predictum est, unitur. Ipse autem Benedictus citatur et non comparens canonice dampnatur et de papatu eicitur.

As far as Benedict personally was concerned, the Kings failed completely. Benedict even refused to meet with them face-to-face. His episcopal adherents, however, were another matter, and there Sigismund and Ferdinand succeeded. By the Treaty of Narbonne December 13, 1415 [Creighton I, 364-365], it was agreed that Benedict's former adherents would summon a council to meet at Constance, and at the same time the Fathers at Constance would summon Benedict's prelates to their Council at Constance. Once united, they would deal with Benedict. On October 15, 1416, Aragon, Castile and Portugal were recognized as the fifth 'nation' at the Council. Benedict was cited again to appear before the Council of Constance, and, failing to do so, was canonically deposed (July 26, 1417). "Benedict XIII" died on May 23, 1423.

Preliminaries

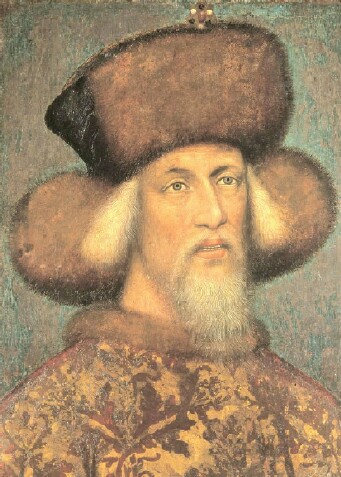

On May 3, 1416, Sigismund, King of the Romans [ left ], set off for England, intent on reaching an agreement with King Henry V. Henry, who had beaten the French at the Battle of Agincourt on October 25, 1415, was an attractive prospect for an alliance for King Sigismund, who had few allies himself; it also had attractions for Henry, who was eager to consolidate his gains against the French in every quarter. The result was the Treaty of Canterbury on August 15, 1416—an alliance against the French and agreement to take the field against them (Rymer, Foedera IX, 377; Lenz, 88-97; Caro, 33-48). Sigismund returned to Constance on January 27, 1417.

On May 3, 1416, Sigismund, King of the Romans [ left ], set off for England, intent on reaching an agreement with King Henry V. Henry, who had beaten the French at the Battle of Agincourt on October 25, 1415, was an attractive prospect for an alliance for King Sigismund, who had few allies himself; it also had attractions for Henry, who was eager to consolidate his gains against the French in every quarter. The result was the Treaty of Canterbury on August 15, 1416—an alliance against the French and agreement to take the field against them (Rymer, Foedera IX, 377; Lenz, 88-97; Caro, 33-48). Sigismund returned to Constance on January 27, 1417.

On July 8, 1417, King Henry V of England ordered the English delegates who were participating in the Council of Constance to adhere to his previous instructions to vote according to his determinations and not their own individual choices (Rymer, Foedera Volume IX, p. 472):

Rex Venerabilibus in Christo Patribus R(ichard Clifford) Londiniensi, N(icholas Babwyth) Bathoniensi et Wellensi, R(obert Hallum) Sarum, J(ohn Catterick) Coventrensi et Lichfeldensi, et J(ohn Wakering) Norwicensi, Episcopis, salutem. Quia, ex insinuatione vestra, credibiliter informamur quod diversi Ligeorum nostrorum in Curia et in Concilio Constanciensi existentes, certa proseque intendunt et nituntur contra nostram intentionem, determinationi et instructioni per nos vobis datis, obedire renuentes et recusantes. Volumus et decernimus quod omnes et singuli ligei nostri in Curia et Concilio praedictis existentes et ad eadem exnunc accessuri (cujuscumque status, gradus, seu conditionis existant) vobis, in praebendo auxilium et consilium, in omnibus sint obedientes et vestris sententiis se conforment, non faciendo consilia aut congregationes particulares cum aliis nationibus vobis inconsultis....

The English delegates, therefore, operated under the "unit rule", as loyal vassals, voting together as the King commanded (in cooperation with King SIgismund against the French), not as they wished. Of the five bishops to whom King Henry's letter was addressed, Hallum of Salisbury died on September 4, 1417 (Eubel I, 435; cf. Rymer 9, 487-488). The other four bishops were elected Adjuncti Electores in the English 'nation'.

Cardinal Francesco Zabarella, the Cardinal Deacon of SS. Cosma e Damiano since 1411 (creation of John XXIII), died at Constanz on September 26, 1417. He had been Archdeacon and Canon of York, Canon and Prebend of Andesakyre in the Church of Lichfield; and Canon of Lincoln [Twemlow, Calendar of Papal Registers VI, 365 (July 14, 1412)].

In October, the Bishop of Winchester Henry Beaufort, uncle of King Henry V, arrived in Constance, as a pilgrim on his way to Jerusalem. His intention is specifically mentioned by King Henry himself in the passport he granted his uncle (July 21, 1417: Rymer 9, 469; and cf. 491). Beaufort had resigned the Chancellorship of England, for the second time, on July 23 (Rymer 9, 472). On the 4th and 5th of September he was at Bruges (Radford, 73). Soon the English delegates at Constance heard that he was in Ulm, and they persuaded the Cardinals to invite him to Constance to discuss matters having to do with the reformation of the Church. The invitation was carried to Ulm by John Catterick, Bishop of Conventry & Litchfield, the President of the English 'nation', who had ample time for discussion as he escorted Beaufort to Constance. Though Beaufort had meetings with King Sigismund and three cardinals, and with the Cardinals and the delegates of the 'nations', little was accomplished—at least according to Fillastre (Finke, Forschungen, p. 227). He does take note, however, of the gossip that was making the rounds in Constance:

Post adventum illius episcopi Vinctoniensis orta est magna suspicio in animis multorum et eciam rumor inter plures, quod ille episcopus Vinctoniensis fingeret se ire in Jherusalem et non vellet ire, quoniam tempus hyemis non patitur navigacionem, nullique aut pauci in hyeme incipiunt navigare, maxime ad tam remotas partes. Et quod per regem Romanorum et Anglicos commentatum et compositum sit, quod ita fingeret et veniret ad concilium, ut esset papa et ad hoc fiebat per medium ejus ista concordia, ut acquireret graciam et laudem in concilo. Aliqui eciam magni prelati per mediatores fuerunt requisiti, ut in hoc consentirent et juvarent. Alique cardinales nitebantur, quod collegium sepe mitteret cardinales ad visitandum eum, alii dicebant non decere fieri. Et ex hiis orta est eciam suspicio.

Was Bishop Beaufort actually campaigning to become pope? The French had their suspicions, but they were paranoid about everything English at the time (See Creighton I, 379 and n. 1). There is also the statement, reported by the literary collector and several times Chancellor of Oxford University Thomas Gascoigne (p. 155), "et quando fuit electus in papam [Martinus VI] alius bonus doctor de Francia electus fuisset, nisi fraus et labor episcopi tunc Wintoniensis, Henrici Beuford, impedivisset". The idea that Beaufort was in Constance to frustrate French designs on the papacy (rather than to advance his own) certainly seems plausible, but this statement, too, may represent French suspicions. And which was this nearly successful French candidate? Jean des Bertrandis, Bishop of Geneva? Unlikely. Or was Beaufort perhaps in the neighborhood of Constance to ensure that the instructions of King Henry issued in July were being obeyed, and to convey the King's most recent (and most secret) commands to the English delegates? (See Radford, 77-80; Creighton I, 392-393). One finds it hard to disagree with the rumor mongers that a winter journey on pilgrimage to the Holy Land by a person like Henry Beaufort was most unlikely. The pilgrimage, in fact, was never carried out.

On October 3, 1417, Cardinal Peter de Alliaco (d'Ailly), the leader of the French party, published a treatise, de modo et forma eligendi Papam (von der Hardt I, 477). On November 1, 1417, he presented draft Canones reformandi Ecclesiam (von der Hardt I, viii, 409-433).

Negotiations on the Voting Procedure

On Monday October 11, according to Filastre's daybook (Finke, "Zwei Tagebucher," 67; Forschungen, p. 228-231), and on the following days the Cardinals and each of the nations elected representatives—eight Cardinals and eight others— to attend a meeting to work out the method of election of a new pope. The meetings took place in a hall in the Convent of the Dominicans. The Committee met on Thursday, October 14, and both the Italians and French expressed agreement on using a simple ballot system. It was a proposition that been circulating, of course, for five or six months already. The Germans, however, loudly objected, pointing out the great numerical disparity between the Italians and the French, on the one hand, and the Germans and English on the other. Cardinal Fillastre objected as well, on the grounds that the system proposed did not treat the College of Cardinals as a College, but as single individuals. The College, he insisted, had the right de jure to elect the pope. Under the system favored by the Italians and the French, it would be possible to elect a pope without the vote of a single cardinal. On Sunday, October 17, the English, proposed that, since they and the Germans had no cardinals at all, if they were each given a vote in the College of Cardinals, they would be agreeable to an election by the College of Cardinals. On Monday the 18th, the Cardinals and the Italians declined to accept the English-German proposal. But on Thursday, October 21, the Spanish delegates, after four days of discussion, agreed. Two of Pope Gregory's cardinals, Antonio Correr ("Bononiensis") and Gabriel Condulmaro ("Senensis") attempted to join in the discussions, but were refused by Cardinal Giovanni Dominici ("Ragusinus") with some harsh words, and were referred to the full Council. On Friday, October 22, Cardinal d' Ailly proposed the method that was similar to what was finally adopted, having each body (Cardinals and the five nations) vote separately, and requiring a two-thirds majority among the Cardinals and a two-thirds majority in each of the the nations. This was immediately opposed by Cardinal Alamanno Adimari of Pisa, who pointed out that only three of the bodies could have the power to hold up the entire election (which could be done by only three persons in each of three nations). The Archbishop of Tours, Jacques de Gelu, who was the leader of the French faction, took the criticism of the French plan badly. Cardinal Fillastre attempted to calm both sides, assuring all that no slight was intended, but going on to observe that in his view the plan did put the twenty-three cardinals at a disadvantage, since it would take eight cardinals to prevent a two-thirds vote. On Saturday, the German faction agreed to the French proposal, in order to prevent (according to Fillastre) the Italian faction from controlling the election from sheer numbers and influence.

On Tuesday the 26th the Spanish representatives joined the Germans in agreeing to the French plan. The cardinals, however, the greater part of whom were Italian, were still holding out They were aware that none of the 'nations' except the Italian wanted an Italian pope, and likewise that the dissentions between one nation and another precluded any possibility of arriving at an agreement on a candidate. The French were aware not only of these considerations, but they had another issue, "propter suspiciones tractatuum, qui fiebant occulte, et requisiciones consensus aliquorum pro episcopo Vinctoniensi Anglico [Beaufort]" (Finke, "Zwei Tagebucher," 70; Forschungen 231). But finally, on October 27, they gave way, saying that they would consent if all of the nations also consented. Finally, on October 28, the agreement was ratified.

On October 30, a committee of twelve was appointed to make preparations for the holding of the Conclave: two Cardinals and two members of each of the 'nations'. They met at the Dominican Convent, and inter alia chose a site for the Conclave—which was not the Episcopal Palace, where the Council of Constance had its headquarters (Fillastre, in Finke, Forschungen, 231-232):

erat autem conclavis locus magna valde domus communis civitatis sita super lacum et nulli domui contigua, in qua erant merces rerum omnium; habens tria magna atria, in ferius per terram, quod remansit civibus plenum mercibus, medium et superius. Et illa duo fuerunt pro conclavi, in quibus facte sunt LVI cellae. Erant enim LIII electores et tres servabantur pro absentibus.

The building which was chosen was the famous Kaufhaus (now called the 'Konzil'), erected in 1388 on the waterfront of the Lake (Ulrich v. Richenthal, pp. 119-120 and 122 ed. Buck). The large hall in which the Conclave met measures 52 yards by 35 yards.

On November 4, King Sigismund returned to Constance from Switzerland. Two Cardinals, Antonio Corarrio and Gabriel Condulmer (both nephews of Gregory XII), approached him immediately with complaints, that, in the election of adjuncti electores, no one from the adherence of Gregory XII had been elected. (Fillastre, in Finke, Forschungen, p. 232). The King immediately convoked a meeting of three cardinals and the Presidents and delegates of the 'nations' and demanded an explanation. They replied that, when the votes were taken, it was without reference to obediences, and, although several members of the obedience of Gregory XII were nominated, none of them received the required majority to be elected. There were, in fact, only four Gregorian cardinals at the Conclave, three of them Venetians and nephews of the late Pope.

A list of the Custodians of the Conclave, appointed by the Cardinals and by each nation, is given in the "Narratio de forma et modo electionis" (Baluzius, 92).

Conclave: A Cardinal's Account

Cardinal Guillaume Fillastre's daybook describes the opening of the Conclave on Monday, November 8, 1417, shortly before sunset (Finke, Forschungen, p. 232-233; "Zwei Taschenbücher", 73-76; cf. Rymer, 523):

Die lune predicta VIII novembris domini cardinales et ceteri electores intraverunt conclave, paulo ante solis occasum. Quod conclave erat majus, pulcrius et propicius ac celebrius quam, ut arbitror, umquam fuerit. Habebat enim LVI cellas, quarum tres pro absentibus servabantur, satis amplas, habente qualibet camerulam, retro lectum satis amplum. Sed erant in duobus atriis alto et basso sub eodem tecto et omnes celle decenter ornate. Multique ibi lecius et quietius steterunt quam in propriis domibus.

On Tuesday, November 9, the Mass was celebrated by the Bishop of Ostia, in the conclave chapel, which had never been used for such a purpose before ("Relatio de papae Martini V electione," in Palacky, p. 665). Filastre notes that the Cardinals and the adjuncti electores did nothing else that day but decide the electoral process, deciding on a written ballot, which would be deposited openly in everyone's sight in an urn . A lengthy discussion took place as to the uncertainties of what would happen with so many electors and with the votes divided up into six parts (the Cardinals and five 'nations' ).

On Wednesday, November 10, in the morning, Mass was heard, and then the electors proceeded to the scrutiny. After the votes had been deposited in the urn, the Cardinal Amadeo de Saluzzo, the primus diaconus, took the ballots from the urn one by one and read the vote and the name of the voter. Each voter acknowledged that it was his ballot and that the vote was correct. When the votes were tallied, no person had two-thirds of the Cardinals, or two-thirds of the 'nationes'. One candidate had three 'nations', another one 'nation'. On that day there was no accessio, and the ballots were burnt. After lunch, the electors did not return to electoral business. The ballots themselves had no fixed form. Fillastre notes that one elector would write: "Ego talis nomino et eligo in Romanum et summum pontificem talem, et in casu quo non erit, nomino et eligo talem." Others were more straightforward: "Ego talis nomino et eligo illum et illum et illum."

On Thursday, November 11, the Feast of St. Martin, the Mass was celebrated by Cardinal Antonio Panciera, the Patriarch of Aquileia (Zurita, 131). In the scrutiny, Cardinal Allarmet (Bishop of Ostia) had received eleven votes of the Cardinals, three from Gallia, five from Hispania, and one from Germania. Cardinal Corrario (the Cardinal of Venice) had ten Cardinalatial votes, two from Italia, three from Gallia, and one from Hispania. Cardinal de Saluzzo had twelve votes from the Cardinals, two from Italia, three from Gallia, one from Germania, and five from Hispania. Cardinal Colonna had eight Cardinalatial votes, four from Italia, one from Gallia, three from Germania, two from Hispania, and six from Anglia. Eight other cardinals received votes. Jean des Bertrands (Bishop of Geneva, an elector in Gallia) had several votes, and several other names were mentioned. It should be noted that, as required by King Henry V, the English bishops were voting together as a group.

Then came the accessio. Cardinal Adimari (Archbishop of Pisa) as spokesman for twenty votes, announced their accession to Cardinal Colonna. A written vote was demanded. When the accessio was counted, Cardinal Colonna had seven more Cardinals (a total of 15) and sufficient additions from the Adjuncti Electores to give him four of the 'nationes'. He was one Cardinalatial vote short of election to the Papacy. Cardinal Fillastre and Cardinal Pierre de Foix, who had not acceeded to anyone, were speaking to each other and were unwilling to accede (invicem loquebantur et timebant accedere). Finally Cardinal de Foix announced, "ad consumacionem hujus operis et unionis ecclesie accedimus nos duo ad dominum cardinalem de Columpna." (Fillastre, 234). It was around 10:00 a.m. (according to Colonna himself: Rymer, 523-524, 536). The vote was made unanimous. Cardinal Colonna, now Martin V, was around fifty years old.

Since he was not in Holy Orders, he was immediately ordained deacon on Friday, November 12, ordained a priest on Saturday the 13th, and on Sunday the 14th consecrated bishop. All of these ceremonies were performed by Cardinal Joannes de Bronhiaco (Jean Allarmet de Brogny), Bishop of Ostia. At his first pontifical Mass, Pope Martin was attended by 140 mitred prelates, according to Thomas Walsingham.

Conclave: An English Version

According to the Historia Anglicana (Volume II ed. H. T. Riley, p. 320) which goes under the name of Thomas Walsingham, there were initially several candidates who received votes: Henry Beaufort (Bishop of Winchester), Richard Clifford (Bishop of London), and Cardinal Pierre d'Ailly (Bishop of Cambrai), but nothing was accomplished on the first or second days:

Die vero Sancti Martini, primo mane, Episcopus Londoniensis venit, et inter omnes Cardinales protulit ista verba: "Ego, Ricardus Episcopus Londoniensis, accedo ad Dominum meum, Cardinalem de Columna." Audito praesenti sermone, repente cuncti praesentes, per Dei gratiam, in eandem consensere personam. Et illico exuerunt eum vestibus suis omnibus, et novis eum revestierunt, ac super altare posuerunt, et deosculati sunt manus ejus et pedes.

Thus, the Historia Anglicana allows Richard Clifford to assume the role that, according to Cardinal Fillastre, was performed by Cardinal Adimari of Pisa. Moreover, if the six English Adjuncti Electores were voting in unity as instructed by King Henry (and which seems to be the case in Cardinal Fillastre's version of events), Richard Clifford would have been precluded from announcing his accedo for Cardinal Colonna. But if his accessio were an historical fact, then the English were not voting as a group, since he would originally have voted for someone else besides Colonna, and his accessio would only have brought a two-thirds majority in his own 'nation'. There is no other source that names Bishop Beaufort or Bishop Clifford as the recipients of any attention on the part of the electors, though Fillastre's remark that Jean des Bertrands (Bishop of Geneva) received several votes even though not a Cardinal, and that there were several others as well, might leave room for Beaufort and Clifford to have been named. If one accepts the proposition that the Cardinals as a group were trying to preserve their own influence—and that seems undeniable—then the English must surely have realized that the Cardinals would never vote to elect a non-Cardinal. Neither the English Adjuncti Electores nor the majority of Cardinals would ever vote for a Frenchman (and the prospect of a return to Avignon), and particularly not for Pierre d' Ailly, whose views on reform and on the position of the Papacy in the Church as a whole were unacceptable. There was no German cardinal at all, and the one Spanish cardinal, Petrus Fernandi de Frigidis, had little prestige; the Spanish had only recently joined the Council of Constance. If the English vote were to be effective, it would have to be for an Italian, and one who would be willing and able to restore the Papacy to its home in the City of Rome. Only Oddone Colonna fit the qualifications. It is impossible, therefore, to prefer an English monastic chronicle to the eyewitness report of Cardinal Fillastre. The details in the English chronicle may well be attributed to national pride.

Conclave: An anonymous version

A manuscript in the archives at Königsberg (Strehlke, in SRP III, 373 n. 4; Creighton II, 364-365) provides yet another account of the Conclave of November, 1417:

Die lune proxime ante festum sancti Martini [November 8] domini cardinales in numero XXIII et de qualibet nacione huius concilii sex prelati aut doctores notabiles in numero XXX intraverunt conclave, et sequenti die videlicet die Martis [November 9] procurati fuerunt omnes eukaristie sacramento. Die Mercurii [November 10] primam electionem fecerunt, quamvis ad effectum et eleccionis finem non pertingerent. Ipso die beati Martini [November 11], sicut singulis diebus factum fuit, fiebant processiones per totam hanc civitatem tam per prelatos huius concilii quam per omnem clerum et religiosos huius civitatis, quamvis (?) cum magna devocione illa die quam aliis. Et dum processio erat prope domum conclavis, facta fuit stacio et statim pueri cantantes alcius quo poterant incipiebant ympnum "Veni Creator Spiritus". Quod audientes domini electores existentes in conclavi magna devocione preventi eciam usque ad lacrimas ceciderunt in facies suas adorantes pro celeri expedicione eleccionis sue viventem in secula seculorum. Tandem ab oracione surgentes ad eligendum more et hora solitis processerunt et compertum fuit dominum meum prefatum XXIII voces habuisse et nullum alium inter electos tot voces habere. Surrexit igitur quidam de dominis cardinalibus exhortans totum cetum dominorum electorum sub hiis verbis vel eorum consimilibus: "Reverendissimi patres! Hic reverendissimus pater, qui omnes alios electos in multis excedit vocibus, quantus sit nacione, quia princeps Romanus, quantusve vita, sciencia et moribus, omnibus vobis adeo notum est, quod ulteriori non egeat declaracione, nec videtur, quod sibi similis in toto cetu huius sacri concilii valeat reperiri. Si ergo placet, omnes in ipsius electionem aspiremus." Et sic domini cardinales primo demum de omnibus nacionibus concorditer et nemine discrepante in ipsum sua vota direxerunt, ita quod ab omnibus instinctu sancti spiritus creditur fere electus.

Mandell Creighton (II, 364) observes that " the writer calls Oddo Colonna ‘dominum meum‘, which might indicate that he was one of Cardinal Colonna's household, and so perhaps an Italian." This inference is no more likely than assuming that an Englishman is a member of a nobleman's household if he addresses the nobleman as ‘Milord'‘. A Pope, once elected, was the lord of all Christendom. The Anonymous says that Colonna had 23 votes (Fillastre makes it 24), and that no one else had as many votes. If Fillastre's count is to be believed, the Anonymous does not tell the whole story: Cardinal de Saluzzo had 23 votes, Joannes de Bronhiaco had 20, and Cardinal Corrario had 16. If one looks only at the cardinalatial votes, Colonna came fourth, after the other three. And, though he did have all six English votes, the sentiment among the 'nations' was by no means clear. It surely took more than some child sopranos singing a Veni Creator outside the Conclave building to sway the voters. In fact the processions and singing were nothing extraordinary. They happened on every day of the Conclave, during every Conclave. Moreover, the speech by an unnamed cardinal, as reported by the Anonymous, might well be the announcement of Cardinal Adimari announcing the accession of twenty votes (many of them probably Italian and German) to Cardinal Colonna, but the Anonymous knows nothing of this. His unnamed cardinal's pietistic speech, without logic or argument, makes no sense.

Coronation of Martin V

Pope Martin V was crowned in Constance, in ceremonies that took place in the Courtyard of the Episcopal Palace (where the Pope had taken up residence) and in the Cathedral of Constance on November 21, 1417, (Lenfant II, 175; 189-193) As he himself stated (Rymer 9, 536);

Ac deinde celeberimis sacrisque, undecimo Kal. Decembris proximo praeteriti, in Constanciensi Ecclesia, juxta ritum praefatae Ecclesiae, cum astantium exultatione permaxima, celebratis sollenniis, cardinalibus ipsis, necnon carissimo in Christo filio nostro Sigismundo Romanorum et Hungariae Rege, illustri regalibus infulis insignito, prelatis, principibus, ducibus, cleri, nobilium et populi multitudine astantibus copiose, ad omnium Creatoris laudem et gloriam, pacem ac unionem praefatae Ecclesiae Orthodoxae, Fidei incrementa, gregisque commissi quietudinem et salutem, nostrae coronationis insignia cardinales ipsi, humillime per nos suscepta, sollenniter peregerunt.

Ulrich von Richental (pp. 125-126 ed. Buck) provides a detailed narration of the event (in German). Other details are provided by Gebhard Dacher (Hardt IV, 1488-1491).

The Historia Anglicana of Thomas Walsingham provides an account of the subsequent ceremonies (pp. 320-321):

Sequenti Dominica, Dominus Papa fecit mane diluculo solemnem processionem, transiens per australem partem ecclesiae versus occidentalem, ubi constitutus fuit quidam clericus, habens canabum et stuppam, te combussit ea, dicens: 'Ecce! pater sancte, sic transit gloria mundi.' Posthaec, eidem die fuit factuam quasi quoddam solarium pro coronatione Papae, in altitudine habens viginti pedes. Prior Sancti Johannis de Klerkenwelle tenuit diadema Papae in officio coronationis. Ipso die, post prandium, Papa equitavit per medium civitatis Constantiae, quem sequebantur in equis omnes Episcopi mitrati et Abbates. Equus Papae phaleratus cum rubeo eskarleto, equi vero cunctorum Episcoporum phalerati fuere candido panno bissino. Et Imperator in hac equitatione tenuit frenum Papae. Cum autem pervenisset Papa ad locum fori, illic obviavere sibi omnes Judaei civitatis, qui porrexerunt sibi, sicut mos est, caeremonias ac legem suam; quas acceptas Papa projecit post tercum suum, dicens: 'Recedant vetera, nova sunt omnia.'

On May 2, 1418, Pope Martin V entered into a Concordat with the German nation (as he did with England and with France), and among the provisions were regulations concerning cardinals (von der Hardt I, pars xxiv, 1056-1086; cf. Gieseler Compendium IV, 302):

Statuimus, ut deinceps numerus Cardinalium Sanctae Romanae Ecclesiae adeo sit moderatus, quod non sit gravis Ecclesiae. Qui de omnibus partibus Christianitatis proportionaliter, quantum fieri poterit, assumantur: Ut notitia causarum et negotiorum in Ecclesia emergentium facilius haberi possit, et aequalitas regionum in honoribus Ecclesiasticis observetur, sic tamen, quod numerum XXIV. non excedant. Nisi pro honore nationum quae Cardinalem non habent, unus vel duo pro semel de consilio et assensu Cardinalium assumendi viderentur. Sint autem viri in scientia, moribus et rerum experientia excellentes, Doctores in Theologia aut in jure Canonico vel civili, praeter admodum paucos qui de stirpe Regia vel Ducalis aut magni Principis oriundi existant, in quibus competens literatura sufficiat; non fratres aut nepotes ex fratre vel sorore alicuius Cardinalis viventis; nec de uno ordine mendicantium ultra unum; non corpore vitiati, nec alicuius criminis vel infamiae nota respersi. Nec fiat eorum electio per auricularia vota solum modo: sed etiam cum consilio Cardinalium collegialiter sicut in promotione Episcoporum fieri consuevit. Qui modus etiam observetur quando aliquis ex Cardinalibus in Episcopum assumetur.

This list of concessions was a reflection, in part, of numerous criticisms of the traditional system of appointing cardinals, for example those of Cardinal Zabarella (von der Hardt I, pars ix, 515-516) and of Cardinal de Alliaco (von der Hardt I, viii, 416-417). Pope Martin's concordat was, nonetheless, a good deal less than the Fathers of the Council had hoped for or expected.

Pope Martin departed from Constance on May 20, 1418 (Andreas von Regensburg, "Concilium provinciale," p. 287)

Anno domini 1418, pontificatus anno primo sanctissimi patris nostri Martini pape V., quo idem feria 6 ante festum S. Urbani de civitate et concilio Constanciensi, in quo electus fuerat in die S. Martini episcopi, se transtulit versus Ytaliam...

He spent three months in Geneva, and then travelled to Milan, where he consecrated the new cathedral. From there he went to Mantua, where he spent five months. He stayed in Florence, at Santa Maria Nova, from February 1419, until September 1420 ("De Martino V," in Muratori, 857, 862).

.jpg)