SEDE VACANTE

Antonio Cardinal Barberini

|

AG SEDE VACA | NTE MDCLV Shield with the Coat of Arms of Antonio Cardinal Barberini, Camerlengo of the Holy Roman Church, surmounted by Cardinal's hat with six tassels on each side; crossed keys above, the Ombrellone over all. |

|

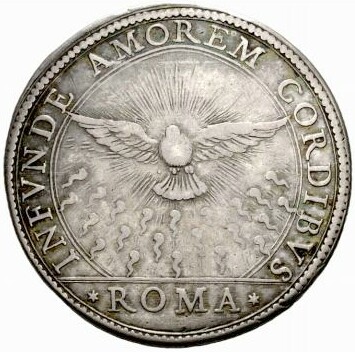

INFVNDE AMOREM CORDIBVS (in exergue:) *ROMA* The Holy Spirit, surrounded by rays and tongues of fire (Pentecost).

|

The Camerlengo

ANTONIO CARDINAL BARBERINI, iuniore (1607-1671), was the son of Carlo Barberini and Costanza Magalotti. He was the nephew of Pope Urban VIII (Maffeo Barberini, 1623-1644), of the Capuchin Antonio Card. Barberini, seniore, (1624), and of Lorenzo Card. Magalotti. His brother Francesco became Cardinal on the election of their uncle to the papacy, and his brother Taddeo became Prince of Palestrina and Prefect of Rome. He was the cousin of Francesco Maria Cardinal Machiavelli (who became cardinal in 1641), and uncle of Carlo Cardinal Barberini (1653). He was Grand Prior in Rome of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem.

The accession of his uncle brought Antonio Barberini and his brothers many positions of power, wealth and influence. He became Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Aquiro in 1627, and Camerlengo of the Holy Roman Church on July 28, 1638, a position which he held until his death on August 3, 1671. In that capacity he managed papal property during the Conclaves of 1644, 1655, 1667 and 1669-1670. He was Abbot Commendatory of the Abbey of Nonantola (1632-1671). The authoritarianism, arrogance and greed of the family ("Quod non fecerunt Barbari, fecerunt Barberini.") brought a strong reaction on the death of Urban VIII. In 1645 Antonio and Taddeo fled to Paris (where Urban VIII had once been ambassador), and remained in exile at the Court of Louis XIV (under the patronage of the Sicilian Giulio Card. Mazzarini) until 1653; he became Grand Almoner of France and a member of the Order of the Holy Spirit. In 1657 he was nominated Archbishop of Rheims, a choice which was approved by Pope Alexander VII. He became Cardinal Bishop of Palestrina in 1661. He died in Rome on August 3, 1671.

The Governor of Rome, named by the Cardinals at the beginning of the Sede Vacante, was Msgr. Giulio Rospigliosi, Archbishop of Tarsus, recently Nuncio in Spain (July 14, 1644—January 1653). He became Cardinal of S. Sisto in 1657, and was Secretary of State of Alexander VII (Chigi) from 1655 to 1667. He was elected Pope Clement IX on June 20, 1667, and died on December 9, 1669.

The Secretary of the Sacred College of Cardinals was Count Federico Ubaldini [Bullarium Romanum Turin edition 16, no. cxxxix, p. 219].

The Ceremoniere were

Carolus Vincentius Carcarasius

Fulvius Servantius

Petrus Antonius della Pedacchia

Christophorus Faccialieta

Death of the Pope

Pope Innocent X (Pamphilj) died on January 7, 1655, at the Palazzo Quirinale. He had been ill since August [Pallavicini, Della vita di Alessandro VII, Lib.II capo xiii, p. 207-208; Novaes, pp. 53-55]; the Diaries of Fulvio Servantio, papal Master of Ceremonies, quoted by Gauchat (Hierarchia Catholica IV, p. 27 n.4), states: Innocentius Papa X, qui iam per aliquot dies valde aegrotaverat et doloribus affectus erat, summa pietate, et ea resignatione qua potuit, praesentis vitae peregrinationi finem imposuit. The expected death of the Pope caused most people of consequence to be gathered in Rome in good time, including most of the cardinals. More than fifty attended the Congregation on January 8, the morning after the Pope's death.

During the last year of the pope's life, according to the commonly retailed story (as in Leti and Trollope; even Ranke was taken in), his sister-in-law Olimpia Maidalchini scarcely ever left his side, completely controlling access to the Pope and to the money she could make and power she could wield through him. In the last weeks of his life, it was said, she would lock him in his room once a week while she removed money and other valuables from the Papal Palace to her own palace. Even with his death she did not flee the inevitable retribution, believing that she could produce a friendly result in the conclave through the exercise of influence and money. She had many to fear, foremost among them Giovanni Battista Cardinal Pallotta, the Dominican Cardinal Vincenzo Maculani, and Domenico Cardinal Cecchini. Her chosen agent is said to have been Cardinal Barberini, though she worked through a number of people, creature of Innocent X, who came to be called her Flying Squadron (Squadron Volante). Cardinal Pallavicini names them (Ranke, p. 36n.): Cardinals Lorenzo Imperiale, Luigi Omodei, Giberto Borromeo, Benedetto Odescalchi, Carlo Pio di Savoia, Ottavio Aquaviva, Pietro Ottoboni, Francesco Albizzi, Carlo Gualtiero, and Decio Azzolino. The dead pope she left to his own fate, not even providing him a proper coffin for his lying-in-state. Or so it is said, with malicious glee. The Protestant T.A. Trollope adopts this nonsense—derived in part from Gregorio Leti—and passes it on to the gullible nineteenth and twentieth centuries, stating that the body of the pope was completely abandoned for three days. The facts, at least for the last two weeks and the period of the Sede Vacante, thoroughly discredit this ridiculous story.

On the night of December 26/27, Pope Innocent was so ill that the doctors formed the conclusion that the Pope was dying. The news was broken to the patient on the 27th by Cardinal Azzolino and the Theatine priest, Father Lolli. Innocent had Prince and Princess Pamphili summoned, and he gave his benediction to his nephew, neice and their children. He also called for Father Gianpaolo Oliva, SJ. Princess Giustiniani and his own sister, who was a nun in a convent in Rome, as well as Donna Olimpia Maidalchini, his sister-in-law, appeared and tried to offer consolation, but, seeing that there was nothing that they could do, they retired. On their departure the Pope had a conversation with his two favorite cardinals, Fulvio Chigi and Decio Azzolino [Priorato, Historia del Ministerio del Cardinale Giulio Mazarino, 406-409].

On Sunday night the Pope had a little rest, but his condition showed no improvement. On Monday it was decided to put a guard on the Monte di Pieta and to transfer to the Castel S. Angelo those who were in prison for major crimes [Priorato, 414].

Fulvio Servantio notes in his Diaries [Gattico I, 459] that, as Pope Innocent felt death approaching, he received the Viaticum on Monday, December 28, 1644, and expressed a desire to speak with his Cardinals. The Pope was in residence at the Quirinale Palace at the time [V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma IX, p. 275, no. 559]. Prince Camillo Pamphili sent his familiares to announce to all the cardinals that hope for the survival the Pope was diminished, and that the Cardinals should assemble at 19:00 hours. Thirty-nine Cardinals appeared; some were prevented by illness, and others were far from Rome on business. Those who appeared were provided seats in the Hall of the S. Officio. The Cardinal Dean, de'Medici, was ill with gout, and had to be carried as far as the chamber of the Consistory in a carrying chair, and from there he was moved in a wheel chair. When the Pope was informed that the Cardinals had assembled, he summoned them into his presence. The Cardinals gathered around his bed, and the Pope made a farewell speech, to which Cardinal de'Medici made reply, expressing his regrets and begging the Pope for his blessing. Various cardinals individually expressed the wish that the Pope would create new cardinals, but the Pope replied that he had summoned the cardinals only to beg pardon for his errors and to exhort them to elect a successor better than him. Cardinal Carlo de Medici replied that they were well satisfied with him, and they would do as he asked in the Conclave. Seeing Cardinal Sforza near his bed, he asked him to note how the glory of a Pope comes to its end [Priorato, Historia del Ministerio del Cardinale Giulio Mazarino, 410-411]. The Pope withdrew his hand from under the sheets, and made the sign of the Cross in blessing, saying, Deus pro sua pietate Vobis benedicat, et mentem aperiat, ut dignam facere possitis electionem, pro ut confido. He thereupon dismissed them, and after they had departed he blessed his familiares as well.

The Forty-hours devotion was ordered for all the churches, to pray for the recovery of the Pope.

On Friday, January 1, Mass was celebrated in the Pope's sickroom, and he kissed the Gospel and the Pax as usual (as the Master of Ceremonies, Fulvio Servantio, who was in constant attendance, carefully notes). The same was done on, Wednesday, January 6, and the Pope received Holy Communion and Extreme Unction. Next day, Thursday, January 7, around 14:00 hours (that is to say, in the night between January 6 and January 7), assisted by the Penitentiaries of St. Peter's and Cardinal Fabio Chigi, the Secretary of State, in the presence of Bishop Ranuzio Scotti, the Prefect of the Sacred Palace (Maggiordomo) since 1643 [Gauchat, Hierarchia catholica IV, p. 124 and n. 5], and the Pope's Sacristan, Msgr. Taddeo Altini, as well as his familiar attendants, he died. He was eighty years and eight months old. His Confessor had been father Gianpaolo Oliva, SJ., future vicar General and General of the Society of Jesus [Pallavicini, Della vita di Alessandro VII, Lib.II capo xiii, p. 210; Novaes X, 55]. The Master of Ceremonies, Msgr. Franciscus Pheobeus, formally announced to the Cardinal Chamberlain S.R.E., Cardinal Antonio Barberini, that the Pope was dead, and thereafter the same to the Dean of the Sacred College of Cardinals, Cardinal de'Medici. The Commander of the Swiss Guard, as soon as the Pope was dead, presented himself and a guard at the palace of Cardinal Barberini and escorted him to the Quirinale. The Cardinal was admitted, along with the officials of the Apostolic Camera. He knelt in prayer, rose, blessed the corpse with holy water, and performed the Recognition (Rogito) of the deceased—the equivalent of preparing and signing the death certificate. He received the Fisherman's Ring from the Pope's Praefectus cubiculi, Msgr. Constanzo Centumflorenus, and appointed members of the Apostolic Chamber to take custody of the Palace. Cardinal de'Medici then called on the three nephews of the Pope, Prince Pamphili, Prince Ludovisi, and Prince Giustiniani, who were waiting together in another room.

After the Cardinal Camerlengo's departure, the body of the pope was turned over to the surgeon; his body was opened, washed, and prepared in the usual fashion (praecordia removed, and enbalmed). The surgeon, Nicolo Larchi, performed the autopsy, removing some seven fiaschi of accumulated water from the body, and a foglietta in the head that weighed fifteen libri. The lungs were found to be attached to the liver. In the gall bladder were found two stones, weighing a total of six ounces.

He was then dressed in papal vestments, including mozzetta and biretta, by the Auxiliantes Camerae, after which the body was exposed for view in the chamber next to the Gregorian Hall, while the Penitentiarii sang the Office for the Dead. At the second hour of the night following his death, January 7, the corpse was carried from the Quirinal Palace to the Vatican, under the direction of Msgr. Servantio. The body was placed on a catafalque in the Sistine Chapel, and dressed by the Penitentiarii of St. Peter's in pontifical vestments. The vestments which the body wore from the Quirinal were given to the Reverend Sacristan. Msgr. Phoebeus arranged with the Cardinal Camerlengo the first of the Congregations, to be held later in the day on the 7th of January at 21:00 hours. On orders of the Cardinal Camerlengo, Msgr. Phoebeus sent a message to the Capitol to have the bell rung, signifying the death of the pope.

The Cardinals

A list of the Cardinals and their dapiferi (butlers) is given in a motu proprio of Alexander VII of August 19, 1656 [Bullarium Romanum Turin edition 16, no. cxxxviii, pp. 209-211], and another list of Cardinals and their conclavists in another motu proprio of the same date [Bullarium Romanum Turin edition 16, no. cxxxix, pp. 218-222]. Conclave in quo Fabius Chisius, nunc dictus Alexander VII. summus Pontifex creatus est, at pp. 180-187, provides a contemporary list. A list is given in P. Gauchat (editor), Hierarchia catholica Volumen Quartum (Monasterii 1935), p. 32. [A slip in Gauchat's entry for Cardinal Francesco Peretti de Montalto (p. 25 no. 53) has him dying in Rome on May 3, 1653; in note 3, however, it is clear that the date should be May 3, 1655, and that Cardinal Peretti Montalto was alive and present at the Conclave of 1655, as the two motu proprio indicate]. Salvador Miranda makes a similar mistake: he has Peretti die in 1655, but entombed in 1653. See also: Ciconius-Olduin IV, p. 715-716 [where they correctly list cardinal Peretti Montalto as in attendance]. Strangely Petruccelli, Histoire diplomatique des conclaves III (Paris 1865), p. 158, says that sixty-nine cardinals entered Conclave on January 18, 1655. Sixty-nine is the total number of cardinals; four came late; three did not come at all.

- Carlo de' Medici (aged 59) [Florentinus], Bishop of Ostia and Velletri, Dean of the Sacred College of Cardinals. A cardinal since 1615 Brother of the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Ferdinand I. Uncle of the Grand Duke of Tuscany Ferdinand II (1621-1670). (died 1666) Agent of the Spanish government inside the Conclave, during which he was in contact with the Spanish Ambassador in Rome, Terranova, and with Incontri, the Ambassador of Modena.

- Francesco Barberini (aged 57) [Romanus], Bishop of Porto and Santa Rufina, sub-Dean of the Sacred College of Cardinals. Later Bishop of Ostia e Velletri (1666-1679) (died 1679) Brother of Cardinal Antonio. Nephew of Urban VIII. Protector of England. Prefect of the SC of the Universal and Roman Inquisition (1633-1679) S.R.E. Vice-Chancellor. [Bullarium Romanum Turin edition 16, no. cxxxix, pp. 217]

- Bernardino Spada (aged 60) [Faenza, not related to the Genoese Spada], Bishop of Sabina. Later Bishop of Palestrina (1655-1661). Legate in Bologna. Former nuncio in France, but not a friend of the Barberini. Protector of the Cistercians, Premonstratensians, Minimi, and the Capuchins. He was a patron and friend of Guido Reni and Guercino.[Cardella 6, 54-55]. He died on November 10, 1661, and was buried in S. Maria in Vallicella [V. Forcella Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma 4, p. 162, no. 392].

- Giulio Cesare Sacchetti (aged 68) [Florentinus], Bishop of Frascati (1652-1655). Later Bishop of Sabina (1655-1663) (died 1663) Bishop of Gravina (1623-1626). Former Nuncio in Spain for Urban VIII (1624-1626). Made Cardinal Priest of S. Susanna by Urban VIII in 1626. Bishop of Fano (1626-1635). Excluded by Spain in the Conclave of 1644. The Venetian Ambassador in Rome, Giovanni Giustinian, however, considered him "di somma bontà, e di grande intelligenza nel maneggio di affari politici e legali, nei quali usa singolar desterità, è acclamato dai buoni, ma all'incontro prova la disavventura della sua continuata esclusione dagli Spagnuoli, dal Gran duca, non meno che da quei cardinali che nel passaio conclave gli fecero ostacolo...." [Barozzi & Berchet (edd.) Relazioni... Serie III-Italia. Relazioni di Roma II (Venezia 1878), p. 155 (December 2, 1651)]

- Marzio Ginetti (aged 68) [Velitrae], A loyal creature of the Barberini. Sent to Germany by Urban VIII to attempt to end the Thirty Years War—at which he failed. Legate of Ferrara. Vicar of Innocent X for the City of Rome, Bishop of Albano. Later Bishop of Sabina (1663-1666), and then Bishop of Porto e Santa Rufina (1666-1671) (died 1671).

- Aloysius (Luigi) Capponi (aged 73), title of S. Lorenzo in Lucina (1629–1659). Archbishop of Ravenna (1621–1645). Bibliothecarius S. R. E. (1649–1659) (died 1659).

- Ernest Adalbert von Harrach (aged 56), Cardinal Priest of S. Prassede (1644-1667) . Archbishop of Prague (1623-1667). Representative of the Emperor Ferdinand III in the Conclave.

- Antonio Barberini, iuniore (aged 47), Cardinal Priest of Sma. Trinità al Monte Pincio. (died 1671) Camerarius S. R. E. Nephew of Urban VIII. His conclavist, Abbe Giovanni Antonio Costa, was a correspondent of Cardinal Mazarin.

- Girolamo Colonna (aged 50) [Romanus], son of Don Filippo, sixth Principe e Duca di Paliano, Gran Connestabile del Regno di Napoli, fourth Duca di Tagliacozzo, Conte di Ceccano, Marchese di Cave, Signore di Genazzano, etc., and Lucrezia Tomacelli. Cardinal Priest of S. Maria in Trastevere. (died 1666). Archpriest of the Lateran Basilica.

- Giovanni Battista Maria Pallotta (aged 61) [Piacenza], Cardinal Priest of S. Pietro in Vincoli (1652-1659). [Caldarola, Diocese of Camerino, Picenum], Cardinal Priest in the title of S. Silvestri in Capite (1631–1652). Nephew of Cardinal Giovanni Evangelista Palotta. Governor of Rome (1628). Nuncio in Vienna (1628–1630). Legate in Ferrara (1631-1634). Co-protector of the Holy House of Loreto (1644-1652). (died 1668).

- Francesco Maria Brancaccio (aged 62) [Neapolitanus], Cardinal Priest of SS. XII Apostoli (1634-1663). Doctor of Theology (Naples, 1620). Formerly Bishop of Capaccio in the Kingdom of Naples (1627–1635). When a servant of his killed a soldier, he was cited to the court of the Viceroy of Naples, but not wanting to acknowledge civil jurisdiction, he fled to Rome. Despite demands for his readmission to his diocese, the Viceroy refused and demanded his replacement. Instead the Pope made him a cardinal, and in 1638 made him Bishop of Viterbo and Toscanella (1638–1670). His career culminated in his being named Cardinal Bishop of Porto e Santa Rufina (1671–1675). (died 1675).

- Alessandro Bichi (aged 59), Cardinal Priest of S. Sabina . Bishop of Carpentras (1630-1657). (died 1657). A loyal agent of the French.

- Ulderico Carpegna (aged 59), Cardinal Priest of S. Anastasia. Former Bishop of Gubbio (1630-1638) and then of Todi (1638-1643). Later Cardinal Bishop of Albano, then Frascati, then Porto (died 1679).

- Marco Antonio Franciotti (aged 63) [Lucca], Cardinal Priest of S. Maria della Pace. Former Bishop of Lucca (1637-1645). (died 1666)

- Stefano Ducati Durazzo (aged 60), Cardinal Priest of S. Lorenzo in Panisperna . Archbishop of Genoa (1635-1664). in which see he was residentiary . (died 1667). Officially of the Imperial faction, but in fact favorable to France.

- Ascanio Filomarino (aged 72) [Naples], Cardinal Priest of S. Maria in Ara Coeli, Archbishop of Naples (1641-1666). (died 1666).

- Marco Antonio Bragadin (aged 64) [Venetus], Cardinal Priest of S. Marco. Former Bishop of Crema (1629-1633), then of Ceneda (1633-1639), then of Vicenza (1639-1655). He died in Rome in his palace at S. Marco on March 28, 1658, at the age of 67 [V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiesa di Roma IV, p. 356, no. 846; Gauchat p. 24 n. 6].

- Pier Donato Cesi, iuniore (aged 72) [Romanus], Cardinal Priest of S. Marcello (died 1656).

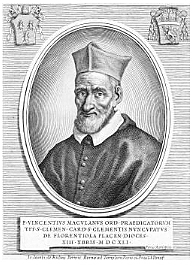

- Vincenzo Maculano, OP (aged 65) [Fiorenzola, Diocese of Piacenza, Duchy of Tuscany], Cardinal Priest in the titulus of S. Clemente (1642–1667). He took the habit at the Convent of the Dominicans at Pavia; his baptismal name had been Gasparo. He was educated at the Dominican Convent in Bologna, and became Inquisitor for Pavia and then for Genoa (November, 1627–December, 1629) [Siri, p. 645; Catalano De magistro sacrii palatii apostolici (Roma 1751) 161]. In 1629 he was named Procurator General of the Dominicans at the Roman Curia, and when the Minister General, Fra Nicolas Rodolphe, set out on his visit to France, he left Maculano in charge as Vicar General [A. Touron, Histoire des hommes illustres de l' Ordre de S. Dominique V (Paris 1749), 296-313; 449-458; at p. 450].

Maculano was named Comissary of the Holy Office by Urban VIII (Barberini) in 1632, a post he held until 1649. In that capacity he presided over the examinations of Galileo in 1633, which were held in Maculano's chambers in the Palace of the Inquisition [Karl von Gebler, Galileo and the Roman Curia (London 1879), 201]; the duties were shared with Fr. Carlo Sinceri, Fiscal Procurator of the Holy Office [Domenico Berti, Il processo originale di Galileo (Roma 1876), p. 82]. Maculano personally delivered the report on the First Examination (April 12, 1633), which he discussed with Pope Urban and some cardinals on April 27 [Gebler, 213 (letter of Maculano to Cardinal Francesco Barberini, April 28, 1633)]. The second examination was on April 30, and the third on May 10—at which Maculano again presided [Berti, 94]. It was also Fra Vincenzo who, on April 30, 1633, on orders of Urban VIII, granted permission to Galileo to reside in the Tuscan Embassy rather than in accommodations of the Inquisition [Berti, 93]. On June 16, Pope Urban met with the cardinals of the Inquisition and demanded that Galileo be interrogated on "intent"—which could involve torture [Berti, 118]. On June 21, Galileo was interrogated on intent by Fr. Maculano [Berti, 119]. On June 22, he appeared before the Cardinal Inquisitors at the Minerva, and was condemned; the Cardinals who were present were:Gasparo Borgia, S.Croce in Gerusalemmethree of the Cardinals, however, did not sign the condemnation: Francesco Barberino, Borgia, and Zacchia. [Gebler, 348-351; Berti, 149; S. Pagano (editor), I documenti del Processo di Galileo Galilei (Vatican 1984)]. On July 2, 1633, it was Fra Vincenzo who personally notified Galileo, in the name of Pope Urban VIII, that he could leave Rome, travel to Siena, and turn himself over to the Archbishop of Siena, to be placed under house arrest [Antonio Favaro, Galileo e l' Inquisizione (Firenze 1907), 103; Gebler, 248].

Fra Felice Centino, O.Min.Conv., S. Anastasia

Guido Bentivoglio, S. Maria del Popolo

Desiderio Scaglio, S. Carlo

Fra Antonio Barberino, O. Min. Cap., S. Onofrio

Laudivio Zacchia, S. Pietro in vincoli

Berlinguero Gessi, S. Agostino

Fabrizio Verospi, S. Lorenzo in Panisperna

Francesco Barberino, S. Lorenzo in Damaso

Marzio Ginetti, S. Maria Nuova

In 1638, Urban sent Maculano to Malta, where he gave demonstration of his scientific skills by designing improvements in several fortresses. He presented his plans to the Grand Master of the Knights of Malta on September 28, 1638 [W. Porter, A History of the Fortress of Malta (Malta 1858), p. 144, 148; the impression is given that he was engaged in surveying, not constructing (as some would think)]. This expedition to Malta took place, of course, before he was named Master of the Sacred Palaces or cardinal. He also performed some restoration work on the Castel S. Angelo and the walls of the City [medals dated An. XX (1643), with the inscription ADDITIS•VRBI•PROPVGNACVULIS: Bonnani, p. 585, no. 22; Spink 1064; Nibby, p. 375 (under Innocent X, 1645)]. The date of Maculano's activity on the walls can be placed in 1643-1644 under Urban VIII, after he had been named a cardinal. The date can be gathered from records of the Apostolic Camera and from the diary of Giacinto Gigli [C. Quarenghi, Le Mura de Roma (Roma 1880), 179-187].

In 1638, Urban sent Maculano to Malta, where he gave demonstration of his scientific skills by designing improvements in several fortresses. He presented his plans to the Grand Master of the Knights of Malta on September 28, 1638 [W. Porter, A History of the Fortress of Malta (Malta 1858), p. 144, 148; the impression is given that he was engaged in surveying, not constructing (as some would think)]. This expedition to Malta took place, of course, before he was named Master of the Sacred Palaces or cardinal. He also performed some restoration work on the Castel S. Angelo and the walls of the City [medals dated An. XX (1643), with the inscription ADDITIS•VRBI•PROPVGNACVULIS: Bonnani, p. 585, no. 22; Spink 1064; Nibby, p. 375 (under Innocent X, 1645)]. The date of Maculano's activity on the walls can be placed in 1643-1644 under Urban VIII, after he had been named a cardinal. The date can be gathered from records of the Apostolic Camera and from the diary of Giacinto Gigli [C. Quarenghi, Le Mura de Roma (Roma 1880), 179-187].

In 1639, Urban promoted Maculano to the post of Maestro dei sacri palazzi (1639-1641), in sucession to Fr. Nicolas Riccardi (1629-1639) (who had also been involved in the Galileo case, as the person who licensed the printing of the Dialogue). Riccardi's cousin, Catarina Riccardi Niccolini, was wife of the Tuscan Ambassador in Rome, Francesco Niccolini [Catalano, De magistro sacrii palatii apostolici (Roma 1751), 158-163]. On December 16, 1641, Maculano was created Cardinal. He was briefly Archbishop of Benevento (1642-1643), though he resigned the See. He was considered papabile in the Conclave of 1644, and it is said that a powerful cardinal of one of the Courts gave him the exclusion, on the grounds that he was an enemy of Cardinal Mazarin [Touron, 454]. He advised Pope Innocent X (1644-1655) to send his sister-in-law, Olimpia Maidalchini, away from the Papal Court—advice which was ignored, though it may have brought him some respect from the more serious cardinals. It is said that Donna Olimpia returned his negative opinion of her at the next Conclave, that of 1655, and worked to destroy his chances for the Papal Throne. Maculano himself, it is said, supported Cardinal Chigi in that election. A very unfavorable character portrait of him at the time is given by Gregorio Leti in Il Cardinalismo [Parte seconda (1668), pp. 291-292]: la lingua di questo Cardinale e mordace in eccesso. e sfodra bene spesso punture molto pungenti, havendosi totalmente dissobligato i Chigi con la libertà del suo parlare, contro i quali parla al presente, che non sono più regnanti con molta franchigia. Egli però stima ciò una gran virtù, dando ad intendere di farlo non già per malignità, ma per zelo, mostrando d'haver la natura nemica delle corruttele del Secolo, non che della Corte, che però non contento di censurare gli altrui vitii, ne' privati congressi, cerca di sermoneggiar negli Oratori publici, pigliandosi non picciolo gusto d'ostentar questa sua tale eloquenza naturale, maravigliandosi tutti, che non essendo egli senza la sua parte di difetti, che si dia à censurare senza riguardo di persona quelli degli altri.... One must, however, consider the source of the portrait. Leti was an apostate, a Protestant, and a French propagandizer. Despite Alexander VII's wish that all cardinals of religious orders should wear the same costume as the other cardinals, Maculano clung to the Dominican habit. He died on February 15, 1667, at the age of 88, and was buried at the Dominican church of Santa Sabina on the Aventine [A. Touron, Histoire des hommes illustres de l'Ordre de S. Dominique (Paris 1748), 449-458]. - Francesco Peretti Montalto (aged 58/60) [Romanus], son of Michele Peretti, Prince of Venafro, and Margarita Savelli, and nephew of Cardinal Alessandro Montalto. He was a great nephew of Sixtus V. Cardinal Priest of S. Girolamo dei Schiavoni/Croati. In 1650 he was appointed, on the nomination of the King of Spain, Archbishop of Monreale in Sicily; his successor was appointed in October of 1656. In 1654 he consecrated Federico Borommeo Patriarch of Alexandria. Peretti died May 3, 1655 (not 1653); he was buried in the Sistine Chapel of S. Maria Maggiore on May 7 [Cardella VII, 22; R. Pirro, Sicilia sacra I (1733), p. 478]. Supporter of Naples (where most of his estates were), and of Spain. Retz, however, had some hope of detaching him and bringing him to vote in favor of Chigi.

- Cesare Facchinetti (aged 46) [Bononiensis], Cardinal Priest of SS. Quattro Coronati. Titular Archbishop of Tamiathis (Damietta) (1639-1672), Bishop of Senigallia (1643-1655), later Bishop of Spoleto (1655-1672). Then Bishop of Palestrina (1672-1679), and then Bishop of Porto. Ended his career as Bishop of Ostia (1680-1683) (died 1683).

- Girolamo Grimaldi (aged 59) [Genoa], Cardinal Priest of S. Eusebio. He had been papal Nuncio in France (1641-1643) He became Archbishop of Aix in August, 1655, after the Conclave (died 1685). Cardinal de Retz alleges that he hated Mazarin and Mazarin returned the favor.

- Carlo Rossetti (aged 40) [Ferrara], Cardinal Priest of S. Silvestro in Capite (1654-1672). Previously Cardinal Priest of S. Maria in Via (1643-1644), and of C. Cesareo (1644-1653). Titular Archbishop of Tarsus (1641-1643), Bishop of Faenza (1643-1676). Cardinal Bishop of Frascati in 1676, then Porto e Santa Rufina (1680-1681). (died 1681). He had been papal Nuncio in England in the 1630s-1640s. . Partisan of the Spanish in the Conclave of 1644.

- Francesco Angelo Rapaccioli (aged 46) [diocese of Narni], Cardinal Priest of S. Cecilia (1650-1657). Bishop of Terni (1646-1656). (died 1657).

- Francesco Adriano Ceva (aged 75), of the Marchesi de Ceva [Mondovi, Piedmont]. He began his career as Secretary to Cardinal Maffeo Barberini when he was Nuncio in France (1604-1607). He was Cardinal Barberini's conclavist in the Conclave of 1623. Canon of the Lateran Basilica (1623). Secretary of Memorials. Maestro di Camera. Nuncio Extraordinary to Louis XIII (1632-1634). Utriusque signaturae Referendarius. Secretarius a secretis of Urban VIII. Cardinal Priest in the titulus of S. Prisca (1643–1655). He died in Rome on October 12, 1655, at the age of 75, and was buried in the Oratory of S. Venanzio in the Lateran Baptistry [V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma VIII, p. 62, no. 164; p. 72, no. 193].

- Angelo Giori (aged 68), Cardinal Priest of Ss. Quirico e Giulitta (died 1662).

- Juan de Lugo, SJ. (aged 71), Cardinal Priest of S. Balbina (died 1660). Died in 1660, at the age of 77. Buried in the Gesu [V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma 10, p. 477 no. 787]

- Domenico Cecchini (aged 65) [Romanus], Cardinal Priest of S. Sisto. Pro-Datary (died 1656).

- Niccolò Albergati-Ludovisi (aged 46) [Bononiensis], Cardinal Priest of S. Maria degli Angeli (S.Maria ad Thermas) (1646-1666), on the petition of Prince Ludovisi, nephew of Gregory XV, a fellow Bolognese (and last of his House), whose follower Albergati was. Referendary of the Two Signatures. Former Archbishop of Bologna (1645-1651). Major Penitentiary (1650-1687). Cardinal Bishop of Ostia – Velletri (1683-1687) (died 1687). He was friendly to the Spanish, considering that much of his income derived from benefices in the Kingdom of Naples.

- Pier Luigi Carafa (aged 73) [Naples], Cardinal Priest of S. Martino ai Monti Referendarius utriusque signaturae. Bishop of Tricarico (1624-1645), consecrated at Rome by Cardinal Cosimo de Torres; he resigned in favor of his homonymous nephew. Nuncio in Germany and Flanders at Liège. His promotion to a cardinalate was opposed by the Colonna. Prefect of the SC of the Clergy (died during the Conclave, on February 15, 1655).

- Alderano Cibo [Genoa], son of the Prince of Massa Carrara. Majordomo of the Apostolic Palace for Innocent X (from 1644). Cardinal Priest of S. Pudenziana (1645-1668), then S. Prassede (1668-1677), then S. Lorenzo in Lucina (1677-1679) then Bishop of Palestrina, then Porto, then Ostia (died July 22, 1700). An imperialist, but well thought of by the French King.

- Fabrizio Savelli (aged 47) [Romanus], son of Prince Savelli, Imperial Ambassador to the Holy See. A professional soldier, he was General of the papal army against the Grand Duke of Tuscany in the War of Castro. The right of the head of the Savelli family to be Custodian of the Conclave (Marshal of the Conclave) in 1655 was usurped by Prince Taddeo Barberini. Cardinal Priest of S. Agostino (August 10, 1647–February 26, 1659). Archbishop of Salerno (from 1642). (died 1659)

- Francesco Cherubini (aged 69) [Picenum], Domestic Prelate and Auditor, Canon of Basilica of S. Peter. Referendary utriusque signorum (Grace and Justice). Cardinal Priest of S. Giovanni a Porta Latina (died 1656) .

- Camillo Astalli (aged 35), Cardinal Priest of S. Pietro in Montorio (died 1663). had a Spanish pension [Petruccelli III, p. 153]

- Jean-François-Paul de Gondi de Retz [French], On the nomination of King Louis XIV, Cardinal Priest without titulus, assigned S. Maria sopra Minerva after the Conclave on May 14, 1655. Archbishop of Paris (1654-1662) (died 1679). Nephew of the Bishop of Paris. He was in flight from France because of the part he played in the Fronde, having escaped from prison in Nantes; he was in debt to the Duke of Tuscany for 4000 crowns, for making it possible for him to reach Rome [Oeuvres du Cardinal de Retz V, p. 5]. At Florence, he had been assisted by Cardinals Gian Carlo de' Medici and his brother, Leopoldo de' Medici. [Memoirs of Retz pp 90-184, esp. 181]. At Siena he stayed with Prince Mathias, third son of Cosimo II [Oeuvres du Cardinal de Retz V, 5]. He arrived in Rome on November 30, 1654, and was given his red hat at a Secret Consistory held by Pope Innocent X on December 7, 1654 [Gauchat, Hierarchia catholica IV, p. 30 nn. 2,3,4]. In December of 1654, Mazarin was sending Hughes de Lionne to Rome to engage in proceedings against Retz; the Procureur General, Nicolas Fouquet, was already at work on the case [Lettres de Mazarin, VI (Paris 1890) pp. 410-412]. The Cardinals of the French faction were under orders from the King to have nothing to do with Retz. He was being courted, however, by the Duke of Terranova on behalf of the Spanish and by Cardinal Harrach on behalf of the Emperor. He finally joined himself with the Flying Squadron. Mazarin was informed of Retz's contacts with the Spanish and the Medici faction [Lettres de Mazarin VI, 435 (February 12, 1655)]. Retz was secretly given copies of Lionne's correspondence, received and sent, by a doctor named Lot [Oeuvres du Cardinal de Retz V, p. 78 n. 4].

- Fabio Chigi (56) [Siena-Rome], Cardinal Priest of S. Maria del Popolo. Vice-Legate of Ferrara, Inquisitor of Malta, Nuncio to Cologne (1639-1651). Bishop of Nardo (1652). Bishop of Imola (1652-1655). Secretary of State of Innocent X. Iuris utroque Doctor.

- Giovanni Girolamo Lomellini (aged 45) [Genoa], Commisary General of the papal armies; Governor of the City of Rome; Treasurer General S.R.E. under Innocent X, Cardinal Priest of S. Onofrio. Legate in Bologna and Ferrara, continued in the post by Alexander VII for three years.. (died 1659).

- Aloysius (Luigi) Omodei (aged 47) [Milan], son of Marchese Carlo Omodei. Cardinal Priest of Ss. Bonifacio ed Alessio (died 1685) .Magister in utroque iure (Perugia).

- Pietro Vito Ottoboni (aged 44) [Venetus], Cardinal Priest of S. Salvatore in Lauro. Bishop of Brescia (1654-1664) (died as Pope Alexander VIII in 1691). The autograph of his diary, from January 9, 1643, to August 12, 1655, survives in the Vatican Library, in Codex Ottobonianus 1073 [V. Forcella, Catalogo dei manoscritti relativi alla storia di Roma II (Roma 1880), pp. 47 no. 98].

- Giacomo Corradi (aged 52) [Ferrara], Auditor of the Rota under Urban VIII. Cardinal Priest of S. Maria in Traspontina, Bishop of Iesi (1653; he was succeeded by Cardinal Alderano Cibo on April 24, 1656). Became Datary of Alexander VII on April 10, 1655 (died 1666)

- Lorenzo Imperiali (aged 43) [Genoa], Cardinal Priest of S. Crisogono (1654-1673). Made a Cleric of the Apostolic Camera by Urban VIII. Vice-Legae of Bologna. Commisary General of the Armies in the Apostolic Camera. Concluded the War of Castro for Innocent X, and was rewarded with the Governorship of Rome and the office of Vice-Chamberlain of the Apostolic Camera (1653-1654). He was named a cardinal in pectore by Innocent X on February 19, 1652. The governorship terminated when the appointment to the cardinalate was announced in March, 1654. Alexander VII made him Legate in Ferrara (1657), and then Governor of Rome for a second time (1660-1662). He was named Legate of the Marches of Picenum (1662). Clement IX made him Protector of the Augustinians (OESA). He died at the age of 61 on September 21, 1673, and was buried in S. Agostino [V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma V, p. 97 no. 292].

- Giberto Borromeo (aged 39), Cardinal Priest of Ss. Giovanni e Paolo. (died 1672).

- Marcello Publicola Santacroce (aged 35) [Romanus], son of Marchese Valerio Santacroce. At the request of King Casimir of Poland, he was named Cardinal Priest of S. Stefano al Monte Celio by Innocent X. Bishop of Tivoli (1652-1674). (died December 19. 1674).

- Baccio Aldobrandini (aged 41) {Florentinus], Cardinal Priest of S. Agnese fuori le mura. (died 1665).

- Giovanni Battista Spada (aged 57) [Lucca, not of the Genoese Spada], Cardinal Priest of S. Susanna Former Prefect of Rome (1635-1643). Legate in Ferrara (from 1654). (died 1675). Firmly in the French camp [Lettres de Mazarin, VI (Paris 1890) p. 448 (March 22, 1655)]. Nephew of Cardinal Bernardino Spada.

- Prospero Caffarelli (aged 57), Cardinal Priest of S. Callisto . (died 1675).

- Francesco Albizzi (aged 61) [Cesena], Cardinal Priest of S. Maria in Via. Practicing lawyer in Cesena. Married Violante Martinelli, and had several children. After her death he migrated to Rome and practiced law there. He was appointed Auditor of the Nunciature in Naples, then Auditor of the Nunciature in Spain. Urban VIII appointed him Assessor of the Holy Office on July 18, 1635. Assistant to Cardinal Ginetti when he was sent as Legatus a latere to Germany. Secretary of the Congregation dealing with Irish affairs. Third secretary of the Congregation dealing with Jansenism. He was created cardinal in the Consistory of March 2, 1654. He served on the SC of the Holy Roman Inquisition, the SC of the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, and the SC de Propaganda fide. He enjoyed pensions both from France (from 1656) and from Spain. He was closely connected with Mazarin [Bildt, Christine de Suède, 40-42]. A member of the Flying Squadron, along with Acquaviva, Ottoboni, Odescalchi, and Azzolini. He wrote a treatise against the claimed right of the exclusiva [L. Wahrmund, Beiträge zur Geschichte des Exclusionsrechtes (1890) 9-17], which produced a number of pamphlets in reply. Cardella (Memorie dei cardinali VII, 110] says, fu uomo di gran testa, di giudizio penetrante, acuto ne' consigli, ma troppo libero nel parlare, e di un naturale collerico anzicheno. He died in Rome on October 5, 1684, at the age of 90, and was buried in S. Maria Transpontina [Gauchat, p. 31, n.3].

- Ottavio Acquaviva d'Aragona, iuniore (aged 45), Cardinal-Priest of S. Bartolomeo all’Isola. Legate in Romandiola. (died 1674).

- Giangiacomo Teodoro Trivulzio (aged 58) [Milan], Prince of Musocco, son of Carlo Emmanuele Trivulzio, Conte di Melzi; he was the fifth cardinal in his family. He had previously been married, with a son and two daughters. Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Via Lata (1653-1655). Became Cardinal Priest of S. Maria del Popolo in 1655. Prior diaconum. (died 1656)

- Giulio Gabrielli (aged 51), Cardinal Deacon of S. Agata alla Suburra, later Cardinal Priest of S. Prisca, Santa Prassede, and S. Lorenzo in Lucina; Bishop of Sabina in 1668. (died 1677).

- Virginio Orsini (aged 40) [Romanus], son of Don Ferdinando, fourth Duca di Bracciano, Prince of the Holy Roman Empire, Signore di Trevignano, etc., Prince Assistant at the Papal Throne, Grande di Spagna di prima classe, Nobile Romano, Patrizio Napoletano, Patrizio Veneto; third Duca di San Gemini, second Principe di Scandriggia e Conte di Nerola, first Duca di Nerola; and Donna Giustiniana Orsini,daughter and heiress of Don Giovanni Antonio Orsini, first Principe di Scandriglia, second Duca di San Gemini e Conte di Nerola and Donna Costanza Savelli dei Duchi di Castel Gandolfo. Prince Virginio was Cardinal Deacon of S. Eustachio (1653-1656), later Cardinal Priest of S. Prassede, then Cardinal Bishop of Albano, then Cardinal Bishop of Frascati (died 1676). Protector of the Armenians and (later) of the Kingdom of Poland.

- Rinaldo d'Este (aged 37) [Modena], son of Elizabeth of Savoy. Cardinal Deacon of S. Nicola in Carcere (died 1672) . Brother of Francesco I, Duke of Modena, who was engaged in negotiations with the French on his own behalf. An enemy of the Barberini since their war over Parma. But when the Spanish offended him by not sharing their councils, he went over to the French, and became their Cardinal Protector and a defender of the Barberini. In its turn, this offended Pope Innocent, and d'Este had to withdraw from Rome for a time.

- Vincenzo Costaguti (aged 43) [Genoa], Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Cosmedin. Gossip had it that he was made a cardinal (July 13, 1643) so that his position in the Apostolic Camera could be sold by Pope Urban VIII, who needed money for his war against the Barberini. Urban had also borrowed money from his family [Bargrave, 59].

- Stefano Donghi (aged 47) [Genoa], Legate in Lombardy and Legate in Ferrara (under Urban VIII). Cardinal Deacon of S. Giorgio in Velabro. He had studied at Bologna but completed his work at Salamanca. Protonotary Apostolic de numero participantium. President of the Apostolic Camera. Bishop of Ajaccio (1651-1655). A supporter of the Spanish interest. Died in Rome of an acute fever on November 26, 1669, and buried in the Gesù.

- Paolo Emilio Rondinini (aged 38) [Romanus], nephew of Cardinal Laudivio Zacchia (d. 1637). Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Aquiro, Bishop of Assisi (1653-1668) [Ughelli-Colet Italia sacra 1, 484]. (died 1668). [both papal documents give his praenomen as Petrus, not Paolo]

- Gian Carlo de' Medici (43), Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria Nuova (1645-1656) [the papal grants of Conclave privileges both assign him S. Maria Nuova]; but sometimes wrongly assigned to S. Maria ad Martyres, or S. Maria in Cosmedin; promoted on the recommendation of the Grand Duke of Tuscany, his brother, and Cardinal Carlo de' Medici, his uncle. . He was a soldier essentially, rather than an ecclesiastic. A supporter of the Emperor, and a supporter of the House of Barberini. Said to have been avaricious and a womanizer (died 1663).

- Federico Sforza (aged 51) [Romanus], son of Don Alessandro Sforza 1572-1631), Conte di Segni, Signore di Valmontone e Lugnano, first Duca di Segni, second Marchese di Proceno, Signore di Onano, twelfth Conte di Santa Fiora, Marchese di Varzi e Castell’Arquato e Conte di Cotignola; and Donna Eleonora Orsini, daughter of Don Paolo Giordano, first Duca di Bracciano and of Isabella de’ Medici Principessa di Toscana. Federico Sforza was Protonotary Apostolic from April, 1621; Vicelegate in Avignon from May 23, 1627. He succeeded Cardinal Antonio Barberini as pro-Vice-Chamberlain S.R.E. Cardinal Deacon of SS. Vito, Modesto e Crescenzia (1646-1656), and subsequently Cardinal Priest of S. Pietro in Vincoli (November 1661) [Gauchat, Hierarchia catholica IV, p. 48]. He was Bishop of Rimini from 1646-1656 [Gauchat, p. 95]. In 1675 he became Bishop of Tivoli. (died 1676) He was ill-disposed toward any of Cardinal Mazarin's schemes, allegedly because Mazarin had rejected him when he was proposed as Nuncio to France [Le Conclave d' Alexandre VII, p. 10].

- Benedetto Odescalchi (aged 43) [Como], Started his career as Cleric of the Apostolic Camera under the patronage of the Barberini. Cardinal Deacon of SS. Cosma e Damiano (1645-1659). Bishop of Novara (1650-1656). Later (1659) Cardinal Priest of S. Onofrio (1659-1676). Bishop of Rome (1676-1689). (died 1689)

- Cristoforo Vidman (aged 36) [Venetus], of the family of the Counts of Ortemberg. Cardinal Deacon of SS. Nereo ed Achilleo (1647-1657); Cardinal Priest of SS. Nereo ed Achilleo (1657-1658); later Cardinal Priest of S. Marco (1658-1660). He began his career in the Curia by purchasing a post as Cleric of the Apostolic Camera. He was promoted to Auditor of the Chamber. He and his brother purchased Venetian nobility. It was on the motion of the Serene Republic that he was created cardinal, at the age of 32, by Innocent X, on October 7, 1647. In 1654 he was appointed Legate in Urbino. He died on September 28, 1660, at the age of 45, and was buried in Rome in S. Marco [V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiesa di Roma IV, p. 357, no. 847].

- Lorenzo Raggi (aged 40) [Genoa], nephew of Cardinal Ottaviano Raggi. Made a cleric of the Apostolic Camera on the same day that his uncle was promoted cardinal, December 16, 1641. After only eighteen months, Lorenzo was named pro-Treasurer-General. He also acted as pro-Camerlengo while Cardinal Barberini was in exile in France. Cardinal Deacon of S. Angelo in Pescheria (died 1687 as Cardinal Bishop of Palestrina).

- Francesco Maidalchini (aged 33) [Viterbo], Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Portico (died 1700). Nephew of Pope Innocent X.

- Friedrich von Hessen-Darmstadt, O.S.Io.Hieros.(aged 37), son of the Landgrave of Hesse and Magdalena of Brandenburg. Born a Lutheran, he converted to Catholicism at Padua in 1634 at the age of 18. On the nomination of Emperor Ferdinand III, because of his military and courtly skills, he was created Cardinal Deacon without deaconry in 1652. He was given S. Maria in Aquiro after the Conclave, on May 31, 1655. {Eggs, Purpura docta VI, p. 422, says that it was S. Maria Nova]

- Carlo Barberini (aged 24) , Cardinal Deacon of S. Cesareo in Palatio (died 1704). Nephew of Cardinal Francesco and Cardinal Antonio. Former Prefect of Rome.

- Carlo Pio di Savoia (aged 32) [Ferrara], Treasurer General of the Apostolic Camera. Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Domnica (died 1689, as Cardinal Bishop of Sabina).

- Carlo Gualterio (aged 41) [Orvieto], Cardinal Deacon of S. Pancrazio. Bishop of Fermo. (died 1673).

- Decio Azzolino (aged 31) [Fermo, Picenum], a protege of Cardinal Giovanni Panziroli, whom he accompanied when he was Nuncio to Spain under Urban VIII (1642-1644), and who later became Secretary of State (1644–1651). Azzolini was Secretary of Briefs to Princes and Secretary of the College of Cardinals under Innocent X [Gauchat, Hierarchia catholica 4, p. 31 n. 6]. It was he (or so it is alleged) who ferreted out the spy (Cardinal Astalli) who had betrayed Innocent X's policies to the Spanish government [Bargrave, p. 67-68; but this is one of Gregorio Leti's fantasies: see Cardella 7, 118]. Cardinal Deacon of S. Adriano al Foro (March 2, 1654; died 1689).

- Baltasar Moscoso y Sandoval (aged 66) [Hispanus], son of Don Lope de Moscoso Ossorio, 6th Conde de Altamira; and Doña Leonor de Sandoval y Roxas (daughter of the 4th Marques de Denia); Cardinal Baltasar's uncle was Cardinal Bernardo de Roxas y Sandoval, Archbishop of Toledo (1599-1618). Bachelor of Canon Law (Salamanca, 1610); Doctor of Canon Law (Siguenza, 1615). Dean of Toledo (1614). He was created cardinal by Pope Paul V in the Consistory of December 2, 1615, at the request of the King of Spain. He was ordained a priest on February 27, 1616, by Francisco Suarez, Bishop of Medauro. Cardinal Priest of S. Croce in Gerusalemme (1630–1665). Bishop of Jaén (1619–1646), consecrated by Fernando de Azebedo, Archbishop of Burgos (1613-1630). [Gauchat, p. 13 no. 36]. Archbishop of Toledo (1646-1665). (Gauchat, p. 13 no. 36; p. 339). John Bargrave, Pope Alexander VII and the College of Cardinals, states (p. 14) that he never came to any conclave. [Fray Antonio de Jesus Maria, O.Carm., D. Baltasar de Moscoso y Sandoval, Presbytero Cardenal (Madrid 1680)] (died September 17, 1665)

- Alfonso de la Cueva-Benavides y Mendoza-Carrillo [Hispanus], Bishop of Palestrina and bishop of Málaga.

- Jules Mazarin (aged 55) [Picenum], Cardinal Priest sine titulo. First Minister of Louis XIV of France. (died 1661)

Preliminaries

On January 8, the Cardinals met in Congregation at 15:00 hours in the Aula Paramenti of the Vatican Palace, with the Cardinal Dean presiding. The Secretary of the College of Cardinals, Msgr. Ubaldini, read the Bull of Julius II Cum tam divino against simony. Each cardinal swore individually, as Msgr. Phoebeus repeated the words, to observe the terms of the bull. Msgr. Ubaldini then read the bull of Pius IV In eligendis Ecclesiarum Praelatis, to which the Cardinals each swore adherence. Msgr. Servantio, since Msgr. Ubaldini was becoming tired, then read the Bull of Urban VIII and the bull of Gregory XV, and an additional oath was extracted. The Cardinal Camerlengo, Cardinal Antonio Barberini, then produced the Fisherman's Ring which was ceremonially defaced. Next the election of Prince Camillo Pamphili, nephew of the late pope, as Captain General of the S.R.E. took place, with 50 favorable votes; only the Orsini dissented. When the next matter, the confirmation of the Governor of the City of Rome, Dom. Arimberti, was put to the vote, he was not confirmed, and a new Governor had to be elected. Msgr. Giulio Rospigliosi, Archbishop of Tarsus, was elected with 51 favorable votes. Monsignor Bressa was elected Governor of the Conclave. Three cardinals—Paleotti, Cybo, and Orsini—were elected to survey the Vatican Palace as a possible site for the Conclave. After the meeting concluded, the Cardinals proceeded to the Sistine Chapel, and the transfer of the body of Pope Innocent to St. Peter's Basilica took place; the body was received by Msgr. Giovanni Battista Scandarola (Scannaroli), Bishop of Sidon, and placed on view in the Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament. Cardinal Barberini caused a stir by appointing Giovanni Rinaldo Monaldeschi as Captain of the Senate and People of Rome, since he was an adherent of the French party. The Spanish, naturally, were infuriated, since he was in a position to facilitate the movements of French troops in central Italy [Priorato, 420-421].

On January 9, thirty-nine cardinals participated in the ceremonies in St. Peter's. Afterwards, the cardinals assembled in the Sacristy of the Basilica for their Congregation under the presidency of Cardinal de'Medici, and received the Conservatori of the City of Rome. On January 10, the Congregation elected Father Nicolaus Zucchi, SJ, as confessor of the Conclave. The doctors and surgeon were also appointed. Cardinals Borromeo and Pio were appointed to supervise the arrangements for the Conclave. Later in the day, the body of the Pope was placed in its coffins, in the presence of Cardinals Ludovisi, Chigi, Omodeo, Ottoboni, Santacroce, Aldobrandini, Vidman, Raggi, Pio and Gualtieri, Princes Pamphili, Ludovisi and Giustiniani, and the Master of Ceremonies Fulvio Servantio. The Congregation received the Orator of the King of Spain, Don Diego Tagliavia d'Aragona, Duca di Terranova [Pallavicini, Libro secondo, p. 227]. He offered Spain's aid for a free election, for which his king would exert all his strength and even shed his blood (There must have been some smiles, and not a few smirks).

Meanwhile, plans were being laid elsewhere. Cardinal Retz revealed in his Memoirs [Oeuvres du Cardinal de Retz V, pp. 21-23; Memoirs of the Cardinal de Retz, p. 191] that he had joined the 'Flying Squadron', having been excluded by the French from their faction and friendship, on orders of King Louis XIV. The 'flying squadron' had been named by the Spanish Ambassador Terranova [Bildt, Christine de Suède, p. 41]. The members of this group met during the Novendiales at S. Maria in Transpontina, with Cardinal Azzolino taking the lead. They examined every possibility, and agreed to work to get Cardinal Chigi elected pope. In their analysis, the problem was Cardinal Antonio Barberini, who could supply many of the necessary votes, but who was apparently committed to the candidacy of Cardinal Sacchetti.

Those of the squadron who had in view the making cardinal Chigi pope, thought that the only way to engage cardinal Barberini to serve him was to oblige him to do it out of a principle of gratitude, by using truly and sincerely their utmost efforts to bring Sachetti to the chair, because they foresaw that all their endeavours would come to nothing, or would serve at least only to unite them to cardinal Barberini in so intimate a manner that nothing could hinder him afterwards from concurring with what they desired. This was the whole mystery of a conclave that hath furnished all those who have been pleased to give us the history of it, with a thousand impertinencies....

"We are persuaded that Chigi is the candidate of of the greatest merit that is in the college, and we are no less persuaded that we cannot make him pope but by doing our utmost in favour of Sacchetti. The worst that can happen, is, our succeeding in bringing Sacchetti to the chair, which, indeed, would not be a very good choice, but not the worst that we could make. In all appearance we shall not succeed in it, in which case we shall bring Barberini to give his vote and interest to Chigi, as well out of gratitude as to keep us all attached to him. We shall bring over to Chigi the factions of Spain and of Medicis, for fear that we should at lst carry it in favour of Sacchetti, and the faction of France likewise, when they find it impossible for them to hinder it."

The squadron agreed unanimously on that course of action. According to Priorato, the Squadrone was composed of Cardinals Lomellino, Homodei, Ottobono, Imperiale, Borromeo, Albizzi, Aquaviva, Donghi, Rondanini, Pio, Gualtieri and Azzolino.

The French faction was comprised of Cardinal Rinaldo d'Este, Antonio Barberini, Alessandro Bichi, and Girolamo Grimaldi. Two other cardinals—Virginio Orsini and Jean Francois Gondi de Retz—were in disgrace with Louis XIV, and were not allowed to caucus with the French faction. Retz joined the Squadrone. Louis XIV often behaved contrary to his own best interests when it came to popes and cardinals and conclaves. Mazarin was pursuing his own private grudges.

The Spanish faction included the two Tuscan cardinals (Carlo de' Medici and Gian-Carlo de' Medici), Ernest Adalbert von Harrach, Girolamo Colonna, Pier Donato Cesi, Francesco Peretti Montaltoi, Juan de Lugo, Fabrizio Savelli, Giangiacomo Trivulzio, Federico Sforza, Friedrich von Hessen-Darmstadt, and Niccolò Albergati-Ludovisi.

On Thursday, January 14, (Novendiales VI) the Orator of the Duke of Tuscany was received by the Cardinals in Congregation; he presented letters from Duke Fernando, which were read to the Cardinals by the Secretary of the College. Then the Orator of Bologna, Marcus Antonius Rainucci, was received. The Cardinals then voted to add a third conclavist for each cardinal, and they drew lots for room assignments. On January 15 (Novendiales VII), the Cardinals met again in the Sacristy of S. Peter's after the Requiem Mass, and appointed Cardinals Ginetti and Ottoboni to vett the conclavists. The list of names of the Masters of Ceremonies was also approved. On January 16 (Novendiales VIII), the Congregation took place again in the Sacristy, and Cardinal Colonna, the Protector of Germany, presented letters from the Emperor. The Emperor offered his aid for a free election, for which he would exert all his strength; it is not recorded that he offered to shed his blood. The Orator of Venice was also received. Following him, the Roman barons appeared. Next day, January 17 (Novendiales IX), after the Requiem Mass, the Funeral Sermon was preached by Count Federico Ubaldini, Secretary of the Sacred College. At the Congregation following the ceremonies, in the Sacristy of S. Peter's, fifty-four cardinals were in attendance. Cardinal d'Este spoke in the name of the King of France. He was followed by the representative of the Duke of Parma, who was followed by Cardinal Orsini, the Protector of Poland, in the name of the King.

The Conclave: The Opening and the first Month

Even before the opening, there were already twenty-six papabili being touted, each of whom had serious points against him [Petruccelli, 148]. Cardinal Bernardino Spada, for example, was showing an unusual energy diring the Sede Vacante, this despite his frequent poor health. He was a person of considerable intellectual gifts, and had been a Cardinal of influence in the reign of the late Pope Innocent X, and had been Nuncio in France (1623-1627), and then Legate in Bologna (1627-1631). The Venetian Ambassador in Rome, Giovanni Giustinian, in his relazione of December 2, 1651, had said of him [Barozzi & Berchet (edd.) Relazioni... Serie III-Italia. Relazioni di Roma II (Venezia 1878), p. 148, 155]:

Spada invecchiato ancor esso nel governo, e molto versato negli affari politici, è un repertorio, sopra cui ricerca Sua Santita le informazioni; gode il bene che il Papa ricorra ad udire la sua opinione nelle occorrenze piu gravi, ma di rato quello di seguitarla, e tanto faceva a suggestione di Panzirolo, non meno che per non accrescergli la stima appresso il mondo ed il collegio, essendo creduto da S. B. quel cardinale propenso anch' esso alla Francia.... l' età di lui [60], le contraposizioni degli Spagnuoli, et altri riguardi non lo redondo considerabile nel futuro conclave.

Gregorio Leti [Histoire des conclaves II, 530-531] alleges that Spada was particularly opposed by Lomellini, Imperiali, and Albizzi, who were jealous of Spada's reputation. And Spada was no friend of Rapaccioli, who was a figure of importance in the "Flying Squadron". Leti also observes that Princes do not like capable Popes, and Cardinals fear one who might wish to govern alone, without giving them any part in the Ministry. The Spanish were also against him.

An anonymous discourse on the three papabili in the Conclave of 1655 [Vincenzo Forcella, Catalogo dei manoscritti relativi alla storia di Roma I (Roma 1879), p. 186, no.581 (Vat. Lat. 8193)] names Carpegna, Maculano and Cecchini as the three cardinals in question.

A lengthy Conclave was likely, and in fact it lasted eighty days and more than 150 scrutinies.

The Opening ceremonies took place on Monday, January 18, the Feast of the Chair of St. Peter in Rome, with the Mass of the Holy Spirit, celebrated by Cardinal Francesco Barberini, the Vice-Dean of the Sacred College. Tthe Dean, Cardinal Carlo de' Medici, was disabled by gout and could not stand or walk. Forty-nine cardinals participated in the Mass. The sermon for the Election of a Pope was preached by Father Giacomo Rospigliosi, doctor in utroque iure (Salamanca), the nephew of Giulio Rospigliosi, titular Archbishop of Tarsus (later Pope Clement IX, who made Giacomo a cardinal). Sixty-two cardinals entered conclave on that day; four others arrived by the 7th of February. Pier Luigi Cardinal Carafa died during the conclave, on February 15. Amazingly, only three cardinals were not present, among them Jules Cardinal Mazarin, the French First Minister. The Spanish Ambassador, the Duque de Infantado, took the opportunity of giving a speech to the College of Cardinals, but he imprudently indicated Spanish support in favor of Cardinal Sacchetti. This infuriated Cardinal Giancarlo de' Medici, who thought that the Florentines and the Spanish were in agreement in opposition to Sacchetti.

The Conclave was not enclosed, however, until the next day, since the necessary construction work had not yet been completed [Priorato, 423-424], and so no scrutiny took place on January 19.

On Wednesday, January 20, in the Sistine Chapel, the Scrutators selected by lot were Francesco Barberini, Ludovisi, and Azzolini; the Revisers were Rapaccioli, Antonio Barberini and de Retz. Carlo de Medici received 2 votes and two Accessits; Francesco Barberini 5 and 5 Accessits; Sacchetti received 10 at the scrutiny and 10 at the Accessit; Ginetti had one at the scrutiny and one at the Accessit; Capponi 3 and 1; Carafa 13 and 8; Chigi 11 and 7; Corradi 3 and 4. Palotta, San Clemente [Maculani], Fachinetti, Grimaldi, Rapaccioli, Giorio, Cecchini, Cherubini, Imperiale, Caffarelli and Albici each received two votes and one Accessit. In the afternoon, the results were similar.

On Thursday, January 21, Sacchetti had twenty-two votes, with scrutiny and accessit combined, an increase of two from the day before. Carafa and Chigi had similar numbers. Nonetheless, that was a far distance from the number of 42 needed at the moment to achieve a canonical election. The afternoon ballot was practically the same [Histoire des conclaves II, p. 497]. On that day, Cardinal Ascanio Filomarino of Naples entered the Conclave [Priorato, 424] . The Histoire des conclaves (p. 497) reports a story that on some day or another (it was January 23) Cardinal Francesco Barberini received thirty-one votes, a great leap from the ten votes he had received three days earlier. On that day, Cardinal Carlo Medici wrote in a letter that his supporters had deliberately voted for Barberini. It was for a laugh. Barberini consoled himself: "Je ne pensais pas sortir pape d'ici, mais j'espère bien y rester si longtemps que j'en sortirai doyen." His supporters, however, did not enjoy the joke. But Medici revealed to Terranova what was really going on; Barberini was being tested as leader of his faction, and the Spanish faction was engaged in a strategy trying to detach "the old guys" from him. Embarassing Barberini weaked his influence [Petruccelli III, 164].

Hughes de Lionne, the French Ambassador Extraordinary, arrived in Rome on January 22, 1655, three days after the Conclave had been enclosed [Valfrey, 205]. He did not have the opportunity, therefore, of making formal courtesy calls on each of the Cardinals, nor was he able to speak confidentially and at length with any of the Cardinals who might support the French candidates. He therefore prepared a speech, with the intention of delivering it somehow in the presence of the members of the Sacred College. His text survives among his papers. He sent the draft, which was quite intemperate, to Cardinal d'Este and the other friends of France inside the Conclave for comment. Major revisions and considerable sweetening was required, but in any case the speech was never delivered orally [Valfrey, 210-214]. In order to communicate with the inside, he could not speak confidentially or write directly to the Cardinals, nor they to him; but there were ways, and Lionne found a willing agent in Melchisedech Thèvenot, a Parisian priest, who was a Conclavist for Cardinal Antonio Barberini. Lionne even got Cardinal Barberini to pretend to be ill and to demand a third conclavist, which was granted. The third man was a Roman priest named Francesco Buti, and he became Lionne's second go-between. Officially, on January 24, he requested an audience with the College of Cardinals, which was granted for the next day.

On January 25, Hugues de Lionne appeared at the Entrance to the Conclave, after the morning scrutiny, as had been arranged. He was met by the three Heads of the Orders (Senior Cardinal Bishop Spada, Senior Cardinal Priest Copponi, Senior Cardinal Deacon Trivulzio) and the Camerlengo Barberini at the Entrance, and they listed to what he had to say through the window. He presented his letters from King Louis XIV to the Cardinals, and related what was in his Instructions. He left a written copy of the speech he would have liked to have delivered, which was accepted by Cardinal Spada and handed over to the Secretary of the Sacred College, Archbishop Rospigliosi. Spada gave a speech in generalities, and Lionne genuflected and departed. On the same day, after lunch (around 20:00 hours), Cardinal Durazzo, Archbishop of Genoa, arrived at the Entrance to the Conclave, was received by the three Heads of the Orders and a number of other cardinals, and was escorted to the Sistine Chapel, where he swore his oaths to observe the Conclave bulls [Fulvio Servantio, Master of Ceremonies, Diaries, in Gattico I, 356].

On January 26, Cardinal Carpegna had his day in the scrutiny. He was the recipient of 28 votes by the time the Accessio was completed. Donna Olimpia must have had fits, since practically no cardinal was more hostile to her interests. Cardinal Spada is said (by Leti, anyway) to have escaped from the Conclave in the afternoon in order to wait on Donna Olimpia (pretending illness: Leti, Biography of Donna Olimpia, 71); he returned with orders to get rid of Carpegna. After lunch (around 21:00 hours), the Cardinals assembled in the Aula Regia and proceeded to the Entrance to the Conclave. As in the case of the Ambassador of France, the Heads of the Orders and the Camerlengo gave audience to the Ambassador of the Emperor, Marcantonio Colonna, Constable of the King of Naples. He presented his letters and gave a speech, to which Cardinal Spada made a brief reply. His letters were opened and read to the Cardinals. In the afternoon scrutiny there were not votes for Cardinal Carpegna, but 27 votes for "Nemini" (No-one, a null vote) [Jauret, 195-196]. What can be said with confidence is that there was continual communication between the Conclave and the Palazzo Pamphili in the Piazza Navona, and, even if Cardinals did not run back and forth, messages certainly did. Donna Olimpia's fear of Cardinal Carpegna is not in question.

On January 27, Cardinal Friedrich von Hesse-Darmstadt entered the Conclave.

On February 7, Cardinal Harrach of Prague arrived from Vienna. He had been sent by the Emperor Ferdinand III to bolster the Hapsburg interests against the French. As he was entering the Conclave he was accompanied by the Spanish Ambassador Terranova, who told Harrach that he had the order of His Catholic Majesty to exclude Sacchetti, and requested that he pass this information on to members of his faction, especially Borromeo and Homodei [Histoire des conclaves II, pp. 499-500]. Hughes de Lionne reported the event immediately, in a letter of February 9, 1665 [Chevalier, no. 1, pp. 63-65]. It was, of course, the worst possible development for the chances of the French candidate. He remarks, however, that there were negative repercussions for the Spanish among the Milanese and the Neapolitans. The number of votes needed for a canonical election had now risen to 44.

On February 15, Cardinal Carafa died. The body was opened by the surgeon, enbalmed, dressed, and laid in state in the Capella Paolina, with a crucifix in his hands laying on his chest. When the Cardinals assembled for the afternoon scrutiny, they first went to the Capella Paolina, and performed the ceremony of Absolution. They then returned to the Sistine Chapel and conducted the afternoon scrutiny. In the evening, the Cardinals assembled again and escorted the body of Cardinal Carafa to the Entrance to the Conclave, where it was passed outside.

On Holy Saturday, Cardinal Gabrielli, who was ill, was removed from the Conclave [Fulvio Servantio, Diaries, in Gattico I, p. 358].

The Parties

Forty-four votes were needed to elect. In dispatches to the Duke of Savoy (March 15 and 22, 1655), Carrette de Bagnasco reported [Petruccelli III, p. 150] that there were six factions among the cardinals: the French group, the Spanish group, the Barbarini faction (with about 18-20 votes at the beginning), the Zealots, the Flying Squadron, and the "faction of God". The 'Faction of God" was composed of the younger cardinals created by Innocent X, those who had not found their way to the 'Squadrone Volante', or to some other group. In other words, they were "wild cards".

According to Pallavicino (214), there were four factions. One, the largest, was led by Cardinal Barberini, the Camerlengo; the cardinals created by his uncle, Urban VIII, mostly adhered to his group. The Spanish interest was led by the Protector of Spain at the Papal Court, Carlo Cardinal de' Medici, the uncle of the Grand Duke of Tuscany Ferdinand II (1621-1670), and Dean of the Sacred College. Medici wrote to the Grand Duke that he was consulting with the Spanish Ambassador, Terranova, as well as with Colonna, Cesi, Montalto (Francesco Peretti), Lugo, Trivulzio, Sforza and Gian Carlo de'Medici. The small French faction was led by Rinaldo Cardinal d'Este, the brother of the Duke of Modena (who was feuding with the Camerlengo Barberini). In  the fourth group were the cardinals created by the deceased pope Innocent (He had created forty cardinals in all; only six had died by the opening of the conclave, though some were associated as 'the Flying Squadron'). The rest were, in fact, without a natural leader, since his nephew Cardinal Pamphili had resigned in 1647 in order to marry Olympia Aldobrandini, Princess of Rossano; and Cardinal Astalli, his adopted nephew, had been disgraced and dis-adopted. These last were inclined to support Fabio Cardinal Chigi, the Secretary of State of Innocent X, who had been the principal papal negotiator at the Peace of Westphalia (in Münster) in 1648 (who was supported by about 18 votes [Novaes, p. 71]).

the fourth group were the cardinals created by the deceased pope Innocent (He had created forty cardinals in all; only six had died by the opening of the conclave, though some were associated as 'the Flying Squadron'). The rest were, in fact, without a natural leader, since his nephew Cardinal Pamphili had resigned in 1647 in order to marry Olympia Aldobrandini, Princess of Rossano; and Cardinal Astalli, his adopted nephew, had been disgraced and dis-adopted. These last were inclined to support Fabio Cardinal Chigi, the Secretary of State of Innocent X, who had been the principal papal negotiator at the Peace of Westphalia (in Münster) in 1648 (who was supported by about 18 votes [Novaes, p. 71]).

Ironically, Chigi's successes at bringing about a peace had been contrary to the designs of Cardinal Mazarin [portrait at left], who was thus unfriendly to Chigi's candidacy (Hanotaux, Recueil, 13):

Quant au cardinal Chigi, il est besoin d'y procéder avec plus de circonspection pur l'exclusion du pontificat, et l'on n'y sauroit apporter trop de soin ni d'application par ce qu' étant créature d' Urbain VIII pour ce qui est de la prélature et d Innocent X à l'egard du cardinalat, il pourroit facilement être favorisé de plusieurs de l'une et l'autre faction, et d'ailleurs il a cet avantage qu' ayant été longtemps hors de Rome, il n' est pas connu en cette cour-là qui, jugeant d'ordinaire par les apparences, le croit peut-être un fort digne sujet sur le fondement de l' emploi qu' il avoit à Munster, quoique cela même nous l' ait fait connoitre plus clairement pour le plus incapable du régime de l' Église universelle qu l' on pourroit choisir. Le Roi ne sauroit donc approuver ni consentir en façon quelconque que le cardinal Chigi soit pape . . .

In fact, as early as 1651, Louis XIV had given instructions that, in a future conclave, two cardinals were to be excluded, Antonio Barberini and Fulvio Chigi [Valfrey,196-199], though Barberini had spent the intervening years trying to patch up his relations with the King and Mazarin. Chigi's prospects were blighted by Mazarin's disfavor, but he had the support of the Spanish Ambassador in Rome. Mazarin, for his part, looked most favorably upon Cardinal Sacchetti, then Cardinal Altieri, then Cardinal Maculani; and he sent Hughes de Lionne as his Ambassador Extraordinary to make sure that the French interest at the Conclave (Bichi, D'Este, Grimaldi and Orsini) understood the King's will. Lionne arrived two days after the Conclave had begun. Though Cardinal Giulio Cesare Sacchetti had been formally vetoed (the esclusiva) by the Spanish Government in the Conclave of 1644, he was still, at the age of 68, a person of great interest (soggeto) in 1655. In the early voting this French favorite regularly drew some thirty to thirty-five votes, about half of the Sacred College, and his strength continued down until mid-March—though he seemed unable to attract the additional support which would make him pope. Mockingly, Cesi called him "Cardinal Thirty-Three". The Spanish were, of course, absolutely against him, as the Duke de Terranova said and then wrote to Cardinal Acquaviva on February 11; the rejection came directly from the King of Spain, Philip IV, and was not a gesture to please the Grand Duke of Tuscany [Petruccelli III, 161]. Sacchetti was still opposed, of course, by the Medici interest and by the Imperialists, despite the fact that the Grand Duke had been offered the title of King of Tuscany independently both by Sacchetti and by Barberini in exchange for his support [Petruccelli III, p. 160 and n. 2]..

Francesco Cardinal Rappacioli, Bishop of Terni, was also a soggetto, but he was young, at only 46, sickly, and opposed by the French interest (in the view of Cardinal Mazarin, at least). Since he was being promoted by Cardinal Facchinetti, Mazarin was sure that he was being supported by the Spanish [letter to Lionne, February 12, 1665, no. cclxxxi]. Mazarin, of course, new very few of the cardinals well, and relied on others to present him with information, on which he based his evaluations; his evaluations were partly based on personal pique, and partly on what was (in his view) good for France. The result were some peculiar antipathies which caused him to fasten on certain cardinals who just did not merit his concern. Cardinal Spada carried an exclusiva to be applied against Rappacioli on behalf of France—which in the event was never used.

The Grand Duke of Tuscany was playing a double game. He wanted to appear to be an accommodating friend to the Spanish king, but he knew that the new pope would be an Italian, and Francesco I was more interested in what the attitude of that new pope would be toward Tuscany than what policy he would pursue with regard to Spain. His duchy was about to be invaded by the Milanese. One person that the Grand Duke did not favor was Cardinal Sacchetti [Petruccelli III, p. 156]. His ambassador in Madrid, Incontri, kept him informed of Spanish thinking, which was conveyed to him by Don Luis de Haro, the King's secretary, who even read Incontri the instructions to be sent to Terranova in Rome. At the same time Don Luis was quite aware (as Haro wrote to the Duke of Terranova) that the Spanish were aware that the Duke of Tuscany was looking out for his own interests [Petruccelli III, 151]. Among other moves, he supported Retz and Grimaldi, since they were in opposition to Sacchetti and would draw votes away from him.

Conclave: Sacchetti's Bombshell

Finally, on February 13, 1655, Cardinal Sacchetti wrote a letter to Mazarin, in a gesture which Valfrey [p. 223] calls "un résolution, que l'on peut qualifier d' héroïque." His purpose was to induce Mazarin to withdraw the threat of a French Veto against Chigi. Sacchetti, the French candidate, had himself been the subject of a veto in the Conclave of 1644. In fact, Sacchetti was attempting to resign his candidacy for the papacy. Lionne considered the letter so important that he had it sent by special messenger on February 15 to Paris. On the same day he had a conversation with Cardinal d' Este at the Entrance to the Conclave (Rota), which he immediately reported to the Comte de Brienne, the King's secretary [Valfrey, p. 224]:

[Cardinal d'Este] me parla... de Chigi, m'avouant que c' était celui dont il pourrait se promettre le plus pour les avantages de sa maison, et ajoutant que c'était le plus grand malheur pour les affaires du roi que ce cardinal se fut brouillé avec la France, parce que, sans cet intérêt et sans les ordres qu'on a de 'exclure, lui, cardinal d'Este avait pu servir tellement avec le parti indépendant qu'il s'en ferait faire chef, et ne rendre pas la faction de France moins considerable dans ce conclave que celle des Espagnols et du cardinal Barberini. Il me sonda ensuite pour découvrir ssi je n'avais point de pouvoir secret en faveur dudit Chigi, et, en tout cas, si je voudrais écrire pour le faire venir. Mais je lui déclarai que nous n'avions nulle liberté en ce fait-ci, et que les raisons qui avaient obligé à cette résolution étaient si puissantes que je n'oserais écrire un seul mot pour obtenir le moindre relâchement. Il me repartit à cela que le péril néanmoins était grand et considérable.

Indeed, as d'Este admitted, the election of Chigi would bring the greatest advantages to his family, and it was consequently difficult for Cardinal d'Este to serve as leader of the French faction. He attempted to ascertain whether Lionne might have some secret instruction in favor of Chigi, and whether he might write to obtain one. Lionne admitted that there were none, and that he did not dare to write to ask. In fact, none of the parties was in control of the Conclave, and anything might happen. The danger for the French was indeed acute. In the meantime, the balloting continued, and the Spanish and Barberini continued to intrigue.

On March 4, Mazarin dispatched a personal letter to Lionne [Lettres VI, cclxxxviii, pp. 444-446]. The message, and the King's (una lettere ostensibile), reached Rome on March 16, and the next day Lionne informed the French cardinals of the purport of the King's dispatch; the threat of the exclusion of Chigi had been revoked [Valfrey, p. 228]:

Par la dépêche que m'a apportée de la cour, du 4 mars, le courrier Acacciaferro, le roi m'ordonne de faire savoir à Mgr le cardinal d'Este, protecteur de ses affaires, et à Mgr le cardinal Antoine [Barberini], grand aumônier de France, que Sa Majesté ayant considéré l'état présent des affaires du conclave et fait d'ailleurs grande réflexion sur ce que lesdits seigneurs cardinaux, en divers temps, et d'autres personnes encore, ont représenté à Sa Majesté, du mérite, probité et rectitude des intentions de M. le cardinal Chigi et, qu'étant élevé au pontificat, il y aurait tout sujet de s'en promettre que l' Église de Dieu in serait bien régie, et qu'aimant la justice au point qu'il fait, la France en recvrait toutes sortes de bons traitements et de grâces, comme d'un véritable père commun, sadite Majesté révoque les ordres qu'elle avait ci-devant donnés à MMgrs les cardinaux de son parti de faire l'exclusion audit seigneur cardinal Chigi, et désire que non seulement ils concourent à son élection, mais qu'ils la procurent, en cas que l'on perde à la fin toute espérance de faire réussir celle de Mgr le cardinal Sacchetti, dont ils devront poursuivre de tout leur pouvoir l'exaltation, sans s'en départir, pour quelque cause ou prétexte que ce puisse être, tant que Mgr le cardinal Barberini et le parti indépendant demeureront fermes et constants en la pratique dudit seigneur cardinal Sacchetti et croiront pouvoir en surmonter les obstacles, par patience et par industrie.

One must note that, even though the French had withdrawn their opposition to Chigi, they were still committed to Cardinal Sacchetti, so long as there was a possibility that he might be elected. It remained to be seen what would happen to the candidacy of Sacchetti, before attention could be given to the prospects of Chigi.

At some point in the Conclave, though it is not possible to say when, an incident took place, involving a Manifesto by Cardinal Albizzi. The Histoire des Conclaves puts it in these terms [II, 501-502]: