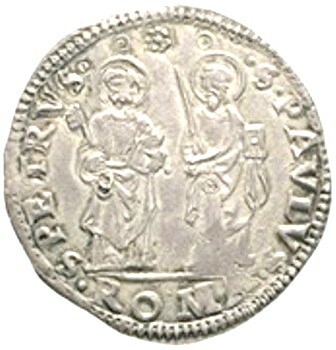

SEDE VACANTE 1521-1522

December 1, 1521 — January 9, 1522

|

AG

|

|

|

Francesco Armellino de' Medici

(July 13, 1470- 1527) was born at Perugia (or in Fossato in the Diocese of Nocera) in 1469 or 1470, the son parents who were "peu honorables" His paternal name may have been Pantalassi, and Armellino his mother's. His father enriched himself by.borrowing large sums from his creditors and then fleeing them. The son moved to Rome and became a solicitor. Julius II made him his secretary, as well as secretary of the College of Cardinals. Because of the son's cleverness along the same lines as his father, Francesco became useful to Leo X, who was perpetually in need of new ways to raise funds. Leo adopted him into his family, and made him a cardinal on July 1, 1517. He was authorized by the Pope to buy the office of Camerlengo from Cardinal Innocenzo Cibò, Pope Innocent VIII's nephew (who had been granted the post by Leo X on August 7, 1521), which he succeded in doing on September 13, 1521 (Pastor History of the Popes Volume 8, p. 98; Luigi Gradenigo, the Venetian Ambassador, in Relazioni, 71; Paris de Grassis, in Hoffmann, 468-469). He was appointed Legate to Umbria and to the Marches, and was made superintendant of finances. But under Adrian VI he was attacked in consistory by Cardinal Pompeo Colonna for his avarice and his huge fortune. Nonetheless he was protected by Cardinal Giuliano de' Medici. When Medici became Pope Clement VII in 1523, his career again prospered; he was preferred to the see of Taranto in 1525 and in 1526 was named pro-Vice-Chancellor of the Holy Roman Church. He lost everything in the Sack of Rome in May of 1527, sought refuge with Clement VII in the Castel Sant' Angelo, and died there. Since he left no will, the pope inherited what was left of his property investments.

The Dean of the College of Cardinals in 1521 was Cardinal Bernardino López de Carvajal (1455-December 16, 1523), the nemesis of Martin Luther. He was named Cardinal Bishop of Ostia and Velletri on July 24, 1521. He had sworn his oath as Cardinal Bishop of Ostia as negotiated between him and Leo X on August 8, with the assistance of Paris de Grassis (in Hoffmann, pp. 470-472).

The Governor of Rome was the Archbishop of Naples, Vincenzio Carafa. He was made a Cardinal by Pope Clement VII [Sanuto, 242].

The Marquis of Mantua was confirmed as Gonfalonier of the Church [Sanuto 32, 272]. He had been appointed by Leo X on July 3, 1521 [Sanuto 31, 13].

The Master of Ceremonies was Biagio Martinelli da Cesena, assisted by D(ominus) Hippolito Morbiolo [G. Constant, "Les maîtres de cérémonies du XVI siècle," Mélanges d' Archéologie et d' Histoire 23 (1903), p. 181 n. 4; Gattico, Acta selecta ceremonialia I (Rome 1753) 318-320]

Death of Pope Leo X

Pope Leo X (Medici) had been ill since October of 1521, probably with malaria. On November 23, the news arrived that the combined papal and Imperial forces, which had been fighting the French and the Venetians in Lombardy and Venezia during the Summer and Fall of 1521, had finall captured Milan [Sanuto 32, 187]. The Cardinal de' Medici, the principal minister of his cousin the Pope, leading the Papal forces had participated in the campaign and had entered Milan on the 21st. The policy of the Medici had always opposed the Venetians, and this was a moment of great pleasure. The French, who were allied with the Venetians, were equally disconcerted. François I had claims on the Duchy of Milan, which he would pursue to his own great cost at the Battle of Pavia in 1525. According to the Venetian ambassador, Gradenigo, however, Pope Leo had a fever on Monday, 25th of November. Nonetheless he returned to Rome from his suburban Villa Manliana (Magliano) that day to be able to participating in the celebrations [Bartholomeo Angilelli, Orator of Bologna, in Sanuto, 239].

He was met by some twenty cardinals, and participated in some festivities in the city, culminating in a grand banquet. That evening there were celebrations in the houses of every cardinal, except Trivulzio, Fieschi, and Pisano—the leading members of the French faction in the College of Cardinals [Sanuto, 204]. Cardinal Thomas Wolsey's Roman agent, John Clerk, wrote to his master on the morning of December 2, alleging (on the authority of Cardinal Campeggio, or so he says) that the Pope had already been dead for eight days [Ellis, 280-281]:

... this mornyng the Cardynall Campegius ded send me word that the Popes Holynes was departyed owt off thys present lyff, God rest his sowell, viij days past: what tyme tydings came off the wynnyng of Mylan his Holynes was forth a sportyng, att a place off his awn callyd Manilian vj. myles owt of Rome, and the selff same day comyng whom to Rome tooke colld: and the next day feel in a fever, whiche was his dethe. At his comyng whome from Manliano, I mett his Holynes, and my thought I never sawe hym mor losty.

However, Pope Leo died on Sunday, December 1, 1521, aged 46, as Paris de Grassis noted in his ceremonial diary (Diario di Leone X, p. 88; Favroni, 227-238):

Die Dominica, quae fuit prima Decembris, horae prope VII, mortuus est Papa Leo Decimus, quin aliquis praevidisset casum suum, nam medici ipsum dicebant leviter aegrotare ex catarrho concepta in Villa Manliana. Parides media nocte ivit in cubiculum mortui papae; et invenit eum mortuum et iam frigidum, quasi nigrum ex catarrho, licet aliqui dixerunt ex veneno. Mane omnes cardinales qui erant in urbe numero vigintinovem venerunt ad palatium... aperto cadavere papae, inventum est cor maculatum et splenae partem corrosam et lienis similiter partem vitiosam, quam tum chiurgi tum phisici viderunt cum stupore, admirati dixerunt pro certo illum fuisse toxicatum . . . .

Paolo Giovio, vita Leonis X (Book IV) speaks more extensively of the pope's death and the charge of poisoning [Vita di Leone X, p. 247-248 ed. Domenici]:

Tantae victoriae nuntio accepto pontifex, cum in Manliana villa esset, incredibili laetitia est affectus; nam eo triduo literae de Helvetiorum ambigua fide acceptae, animum incerta et ancipiti spe victoriae suspensum solicitis cogitationibus excruciarant. Nec multo post, priusquam coenaret, obriguit, sensimque exorta est febris a quodam miti tepore longe lenissima, sed quae ei suprema extitit; ob id sequente die in Urbem est revectus, iam certius ac plenius erumpente morbo; pessimumque omen imminentis mortis in ipso cubiculi limine accepit in quo constiterat architectus ligneam offerens sepulchri effigiem, quod tum insigni marmoris caelatura Henrico regi in Britannia parabatur. Sed ea febris, quod ex intervallis lacesseret, a medicis adulantibus aut iudicio deceptis, aliquamdiu neglecta, adeo vehementer demum incubuit ut pene priusquam morbus dignosci posset et fatalis hora sentiretur, turbata ratione sit ereptus; paucis tamen ante horis quam e vita migraret, supplex, iunctis elatisque manibus atque oculis in coelum pie coniectis, Deo gratias egit, constantissime professus, sed vel funestum morbi exitum aequo pacatoque animo laturum, post quam Parmam Placentiamque sine vulnere recuperatas, honestissima de superbo hoste parta victoria, conspiceret. Vixit annis quadraginta septem, imperavit octo totidemque mensibus et diebus undeviginti.

Fuere qui existimarent eum indito poculis veneno fuisse sublatum; nam cor eius atri livoris maculas ostendit et lien prodigiosae tenuitatis est repertus. quasi peculiaris et occulta veneni potestas totum id visceris exedisset. Ob id coniectus est in carcerem Barnabos Malaspina minister a poculis, non obscuro indicio, quod Leonem, pridie quam decumberet, in coena post haustum vini calicem, statim obducta et tristi fronte ab eo quaesivisse constabat undenam sibi adeo amarum et insuave vinum propinasset. Adauxit quoque patrati sceleris suspicionem, quod ipse sub auroram, quum septima noctis hora pontifex expirasset, specie venandi cum canibus Vaticanam portam exivisset, adeo ut a praetorianis uti fugitivus caperetur, his scilicet admirantibus dissolutum hominis ingenium, qui intempestivas absque ullo pudore quaereret voluptates, quum tota aula extincto beneficentissimo domino in lachrymis et luctu versaretur.

The rumor of poisoning is also reported by Girolamo Bonfio in a letter to his barber on December 5, a copy of which found its way to Senator Marino Sanuto in the offices of the Venetian government [Sanuto, 233-234]. A more measured opinion, and one with some considerable likelihood of truth, was presented to the Signoria of Bologna by Bartolomeo Angilelli, reminding them that the pope suffered from a fistula which was the despair of his doctors, and that he appeared to be suffering from intermittent fevers which assailed him each evening (Sanuto, 239-40). An official examination of the pope's cupbearer, who was accused of administering poison, absolved the man and concluded that the pope did not die of poison but of catarrh [Paris de Grassis, in Hoffmann, p. 480-481]. Both the Orsini and the Colonna were in arms and the city of Rome was closed down tightly. All the banks were closed. [Sanuto, 239]. Cardinal Armellini, nonetheless, found his way to the Florentine bankers, who provided a loan for the pope's funeral, since the Apostolic Chamber was empty and heavily in debt.

On Monday, December 9 [Burmann's Conclave narrative, p. 146, incorrectly puts this on the 11th], the Cardinals assembled in the Vatican Palace, where they elected as Captain of the City Constantine Comnenus, Doke of Achaia and Macedonia; they also elected, as Governor of the City of Rome, the Archbishop of Naples, Vincenzo Carafa. The Burmann Conclave narrative correctly states that Cardinals de' Medici, Cornaro, Passerini and Cibo were not present at the meeting; Medici and Cornaro were still on the road. .After the Congregation, the body of the late Pope was carried to the Basilica of St. Peter in solemn procession. The official funeral took place [Sanuto, 236] and the first of the novendiales masses was held in the Sistine Chapel of the Basilica, the Dean of the Sacred College presiding. There the bull of Julius II against simony was read by Blasius, the Secretary of the Sacred College. Twenty-eight cardinals were present. Cardinal Alessandro Cesarini, former papal protonotary, was appointed to make the necessary preparations for holding the conclave. [Paris de' Grassis, in Hoffmann, 482-483]. The Novendiales would conclude on the 18th, and therefore the Conclave was scheduled to begin on the 19th [Sanuto, 239]..

On Tuesday, the 10th, Cardinal Cornaro arived from Venice, and on the 11th five more. Two more arrived on the 12th.

The Cardinals

There were forty-eight cardinals at the time of the pope's death. Cardinal Ferrero (Ivrea) was detained at Pavia, but finally arrived in time for the Conclave [Bergenroth, pp. 385-386 no. 371]; three other French cardinals did not even attempt the perilous journey. A full list of living cardinals is provided in Sanuto (pp. 326-329), but it includes Adriano Gouffier de Boissay who died on November 8, 1517; and Jacobus de Croy, who died on January 6, 1521—giving a total of 50 cardinals (the correct number is 48). Another list is preserved in the Archives at Simancas, copied from the Papal Archives by Johannes Berzosa at the command of King Philip II of Spain; it is highly inaccurate. for example, listing Grimani, Soderini, Bonifacio Ferrero, and Gonzaga as absent [Bergenroth, no. 375, pp. 388-390]. Another list of the cardinals who were present in Curia at the death of Leo X is given in the Conclave narrative of Conrad Burmann [pp. 144-146], but it is inaccurate; it lists both Medici and Cornar as present. Medici was in Milan, and Cornar was in Venice (enjoying the election of his father as Doge of Venice); even as a list of living cardinals it is incomplete, with only fourty-four names in total.

- Bernardino de Carvajal (aged 57) [Spanish], Suburbicarian Bishop of Ostia and Velletri, Dean of the Sacred College (Senatus princeps, in the words of Paolo Giovio, Decano del colegio, according to Bernardo Rutha in Luzio, p. 390), once Cardinal Priest of Santa Croce in Gerusalemme (1495-1507) The only remaining schismatic cardinal of Pisa (1511); he was reinstated by Leo X on December 13, 1515.

- Domenico Grimani (aged 60), Suburbicarian Bishop of Porto e Santa Rufina (died August 27, 1523) Administrator of Urbino (1514-1523). His cardinalate had been purchased from Alexander VI in 1493 by his father, Antonio Grimani, for the sum of 30,000 ducats [Norwich, History of Venice, p. 436]. Antonio Grimani was elected Doge of Venice on July 6, 1521, at the age of 87. Cardinal Grimani arrived in Rome from Venice on December 14, 1521.

- Francesco Soderini (aged 68) [Florence], Volaterranus, Suburbicarian Bishop of Palestrina

- Alessandro Farnese (aged 53) [Roman], Suburbicarian Bishop of Frascati, Bishop of Parma (1509-1534). Bishop of Rome (1534-1549). He had not been ordained priest until 1519; he had a mistress (up to 1513), three sons and a daughter.

- Niccolò Fieschi (aged ca. 65) [Genoa], Suburbicarian Bishop of Sabina

- Antonio Ciocchi del Monte (aged ca. 59) [Arezzo], son of Fabiano Ciocchi, a Consistorial Advocate. Suburbicarian Bishop of Albano since July 21, 1521; formerly Cardinal Priest of Santa Prassede (1514-1521), and S. Vitale (1511-1514), Bishop of Pavia (1511-1521), Archbishop of Siponto (1506-1513), Bishop of Città di Castello (Tifernum) (1503-1506), Auditor of the Rota, It was he who recommended to Julius II the strategy of convening the Lateran Council as an antidote to the schismatic Council of Pisa [Eggs, Purpura Docta Supplementum, p. 258].

- Pietro Accolti (aged 66) [Florentinus], Cardinal Priest of S. Eusebio, former Professor of Law at Pisa "Cardinal of Ancona" Bishop of Ancona (1505-1514); he resigned the see in favor of his nephew Francesco Accolti. On November 6, 1521, he wrote to M. Robertet, French Secretary of State and Royal Treasurer, asking him to obtain King Francis' permission for Accolti to resign the Bishopric of Arras in favor of his nephew Benedetto [Molini, Documenti di storia italiana I, no. LXVII, pp. 130-131]; he did not resign until 1523, and was not succeeded by his nephew [Eubel III, p. 122].

- Achille de Grassis (65) [Bologna], Bononiensis, Cardinal Priest of S. Maria in Trastevere. Bishop of Bologna (1511-1523).

- Matthias Schiner [Schinner or Scheiner] (aged 56) [Mühlbach, Switzerland, not Sion], Cardinal Priest of S. Pudenziana. Sedunensis. Formerly Canon of Valeria in the Diocese of Sion, Dean of Valeria, Bishop of Sion (1499-1522) in succession to his uncle. He brought the Swiss over to the side of Julius II in his war against the French, being hostile to King Louis XII ever since the rebuff of a petition for a benefice from the monarch; Schiner even led an army across the Alps to Verona [Gallia christiana 12, 752-754; Eubel III, p. 295]. He held the administration of the Diocese of Novara in February and March of 1513; and likewise of Catarro. [See Eubel III, p. 260 n.]. In 1521 he alienated his own Swiss people by supporting the Emperor against the King of France. He was with the Imperial army in Lombardy in the Summer and Fall of 1521, leading troops and actively engaging in the fighting, especially around Brescia and Bergamo. He left for Rome on Tuesday afternoon, December 3 [Marino Sanuto Diaria 32, p. 227]. During the Novendiales he spoke in one of the Congregations in favor of the election of Cardinal de' Medici [Sanuto, 284, a letter of Alviso Gradenigo, the Venetian Orator, of December 21, 1521]. He died in Rome on September 30/October 1, 1522, under suspicion of being poisoned (according to Paolo Giovio).

- Lorenzo Pucci (aged 63) [Florence], Cardinal Priest of SS. Quattuor Coronati, Professor of Law at Pisa, Datary of Julius II and Leo X, Major Poenitentiarius 1520-1529. He died in 1531, and was buried at the Minerva [V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma I, p. 441, no. 1710].

- Giulio de' Medici (aged 43), Cardinal Priest of S. Lorenzo in Damaso, Cardinal Vice-Chancellor of the Holy Roman Church, Cousin of Leo X (died 1534) His conclavist was Girolamo Aleander, former Vatican Librarian and future Cardinal (Paquier, L' humanisme 297-298). Bishop of Florence (1513-1523) and Archbishop of Narbonne (1515-1524), formerly Bishop of Embrun (1510-1513). On June 4, 1521, it was reported by Juan Manuel, Imperial Ambassador in Rome, that the Pope had given Cardinal de' Medici the administration of the Bishopric of Worcester, which had just fallen vacant [Bergenroth, p. 354, no. 340; Le Neve, Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae III, 62]. The Venetians received news on July 7, 1521 that the Emperor had given Medici the bishopric of Toledo, which the Pope approved [Sanuto 31, p. 10 and p. 13]. Medici received a pension of 10,000 ducats a year from the bishopric of Toledo, granted in 1522 [Duke of Sessa to Charles V (February 24, 1524): Bergenroth, no. 621, p. 605]. The Emperor and the Pope had just formed a new alliance in June, and the Venetians were frightened by Imperial successes. On October 10, it was reported at Venice that Medici, Legate in Bologna, was with the papal army only ten miles from Cremona [Sanuto 32, 15]. On November 16, he was on the banks of the Ada, with the Marchese of Mantua and the Marchese of Pescara. On November 19, Imperial forces captured Milan, and thereafter Lodi, Parma, Pavia, and Piacenza [Sanuto 32, 175; and see the Marchese of Mantua's letter to his mother, in Sanuto, 183-185]. Cardinal Medici himself was in Milan on the 19th and was joined by Cardinal Schiner [Sanuto 32, 162 and 187] Medici was still in Milan as Papal Legate and as governor of Milan in place of Duke Francesco Sforza, who supported the French [Sanuto 32, 190] when the Pope died. He was not in Rome for the official Novendiales.

- Giovanni Piccolomini (aged 46), [Senensis], Cardinal Priest of S. Balbina, Archbishop of Siena (1503-1529). (died 1537)

- Giovanni Dominico de Cupis (aged 28), Tranensis, Cardinal Priest of S. Giovanni a Porta Latina, Bishop of Trani (1517-1551) (died 1553). Earlier he had been Canon of the Vatican Basilica. Secretary of Julius II. Secretary of Leo X

- Raffaele Petrucci (aged 47) [Senensis], Cardinal-Priest of S. Susanna (died December 11, 1522). Bishop of Grosseto

- Andrea della Valle (aged 56), Cardinal Priest of S. Agnese in Agone (died 1534).Bishop of Mileto (1508-1523), Bishop of Cotrona (1496-1508 and 1522-1524).

- Bonifacio Ferrer(i)o (aged 45) [Vercelli in Piedmont], Cardinal Priest of SS. Nereus and Achilles, Bishoip of Ivrea (a village between Vercelli and Aosta) (died 1543) Iporegiensis. The Imperial Ambassador, Juan Manuel, sent someone to meet him, with a safe-passage [Bergenroth, p. 384 no. 369; p. 386 no. 371]. He arrived in Rome and entered the Conclave by December 28 [Letter of the Imperial Ambassador, Juan Manuel, December 28, 1521: Bergenroth, p. 386; and p. 390]

- Giovanni Battista Pallavicini (aged 41) [Genoa], Cardinal Priest of S. Apollinaris, nephew of Cardinal Antoniotto Pallavicini. Bishop of Cavaillon (1507-1524) [Gallia christiana 1, 953-954]. Previously Canon of Cumae (died 1524) Doctor of Law, Padua

- Scaramuzzia Trivulzio (aged ca. 56) [Mediolanensis], Cardinal Priest of S. Ciriaco in Thermis (1517-1527). Doctor in utroque iure (Pavia). Former Bishop of Como (1508-1518). Comensis Professor of Civil and Canon Law at Perugia. Councillor of State of Louis XII of France. He defended Julius II against the schismatic council of Pisa. Protector of France before the Holy See. Administrator of Piacenza (1519-1525) [Ughelli-Colet II, 234]. Administrator of the diocese of Vienne (1527). He died in Rome on August 3, 1527 [Eubel III, p. 15 no. 17].

- Pompeo Colonna (aged 42) [Romanus], grandson of Antonio Colonna, son of Girolamo Colonna (d. 1482) and Vittoria Conti, nephew of Prospero Colonna. Cardinal Priest of SS. XII Apostoli. Abbot of Subiaco (1508-1532), Bishop of Reate (1508-1520). Administrator of the diocese of Potenza (January, 1521-1526), Archbishop of Monreale (1530-1532) (died 1532)

- Dominico Giacobazzi (aged 77) [Romanus], Cardinal Priest of S. Clemente and of S. Lorenzo in Panisperna in commendam. Doctor of Canon Law. Made a Consistorial Advocate by Innocent VIII in 1485. In 1490 (or 1493), Innocent made him Auditor of the Sacred Roman Rota; he eventually became Dean. Canon of the Vatican Basilica (1503). Appointed Bishop of Lucera (Nocera) (1509-1517) by Julius II. President of the Roman Arch-Gymnasium. Vicar of Rome [L. Cardella Memorie de' Cardinali IV, p. 28]. Created Cardinal Priest of S. Lorenzo in Panisperna by Leo X on July 1, 1517. [C. Cartharius, Advocatorum Sacrii Consistorii Syllabus (Roma 1656) lx-lxi] (He died in 1528)

- Lorenzo Campeggio (aged 47) [Bologna], Cardinal Priest of S. Anastasia (died 1539) Bishop of Feltre, and Count Palatine. Doctor in Canon and in Civil Law, Padua and Bologna

- Ferdinando Ponzetti (aged 77) [Neapolitanus, but of Florentine origin], Cardinal Priest of S. Pancrazio, Former Treasurer of the Apostolic Camera.. Bishop of Molfetta (1517-1518). Later Bishop of Grosseto (1522-1527). He died in 1527. Molfetta

- Francesco Armellini de' Medici (aged 51) [Perugia], Cardinal Priest of S. Callisto (died 1527, in the Castel S. Angelo) Cardinal Camerlengo. Former Secretary of Julius II and Secretary of the Sacred College of Cardinals.

-

Tommaso de Vio, OP, Cajetanus (aged 52) [Gaeta], Cardinal Priest of S. Sisto (1517-1534) Bishop of Gaeta (1519-1534). Former Master General of the Order of Preachers (Dominicans). Appointed by the Duke of Milan to teach theology at Pavia. In 1499 and 1500 he taught at Mantua and Milan. He had been brought to Rome by Cardinal Oliviero Carafa and was given a chair at the Roman Archiginnasio. On May 30, 1501, he was elected Procurator General, and appointed Prefect of Studies in the Apostolic Palaces for the next seven years. Pope Julius II then appointed him Vicar General of the Dominicans on the death of the Superior General in August, 1507, until the next Chapter, which met in June, 1508. At that Chapter he was elected Superior General of the Order. He worked with Julius II to end the threatened schism of the Conciliabulum of Pisa in November, 1511. He sent three Dominican doctors to argue the Pope's case, and he himself published a defense of papal authority. He held General Chapters of the Order at Geneva in 1513 and at Naples in 1515. He was still Superior General when named a cardinal in June, 1517. On April 13, 1518, he was appointed Legatus a latere to the Emperor Maximilian and to the King of Denmark, in place of Cardinal Farnese, who was unable to carry out the mission due to illness [Paris de Grassis, Il Diario di Leone X (ed. Armellini, 1884), p. 67]. A treaty was arranged against the Turks with the Emperor and the King of Sweden, Denmark, and Norway, Christian II. He was also given instructions about Luther, either to reconcile him to the Church, or to declare him a Heretic. Luther, however, was protected by the University of Witemberg and the Elector of Saxony. The Cardinal was with the Emperor Maximilian when he died at Linz on January 12, 1519. He worked successfully in the private meetings of the Imperial Electors to bring about the election of Charles V, in June 1519, in accordance with the wishes of Pope Leo X. Cardinal de Vio returned from Germany on September 5, 1519 [Eubel III, p. 16, n. 7]. De Vio was sometimes called "Minerva", from the Dominican headquarters at S. Maria sopra Minerva. He died in Rome on August 10, 1534, and was buried at the Minerva [V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma I, p. 443, no. 1714-1715]. [A. Touron, Histoire des hommes illustres de l' Ordre de S. Dominique IV (Paris 1747), 1-27]. He was the author of numerous tracts on theology and biblical exegesis.

- Silvio Passerini (aged 51 or 52), Cardinal Priest of S. Lorenzo in Lucina. Datary of Pope Leo X, Bishop of Cortona (died 1529) On December 19, 1520, he had been named Legate in Perugia [Paris de Grassis Il Diario di Leone X (ed. Armellini, 1884), p. 81].

- Cristoforo Numai, OFM Obs. (aged ?) [Forlì], Cardinal Priest of S. Maria in Aracoeli (1517-died 1528). Former confessor of Luisa of Savoy, mother of King François I. Former Minister General of his order (1517). Doctorate (Sorbonne). He was suffering from podagra (gout) [See the obsequious letter to Queen Luisa, January 11, 1520. in Molini, Documenti di storia italiana I, no. xxxiii, pp. 72-73]

- Egidio (Canisio) of Viterbo, (aged 49), Cardinal Priest of S. Matteo (died 1532) Legate of Julius II to Venice and to Naples. Vicar General of the Canons Regular of S. Augustine, and then Minister General of his order (1508). In 1515 he was Nuncio of Leo X to the Emperor Maximilian, to arrange peace with Venice and Urbino.

- Guilelmus Raimundo de Vich (aged 51 or 61) [Catalan], Cardinal Priest of S. Marcello (died 1525), Archbishop of Barcelona (1519-1525). His brother had once been Spanish Ambassador in Rome.

- Marco Cornaro (aged 43 or 44) [Venice], Constantinopolitanus, Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Via Lata (died 1524) Bishop of Padua The news of the death of the Pope was received in Venice on December 4, and Cardinal Cornar set out on December 6 for Rome [Sanuto 32, 208 and 251]. Corner and Grimani did not get along well with each other [Sanuto 32, p. 208].

- Sigismondo Gonzaga (aged 51) [Mantua], son of Marchese Federico I "Il Gobbo" and Margherita the daughter of Duke Albert II of Brunswick. Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria Nuova (died 1525). Brother of the Marquis Francesco II of Mantua, and thus brother-in-law of Isabella d' Este. Papal Legate in the warof the League in 1512.

- Innocenzo Cibò (aged 30) [Genoa], Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Domnica (died 1550). Grandson of Pope Innocent VIII, Nephew of Pope Leo X, Archbishop of Genoa, 1520-1550. Arrived in Rome on December 14, 1521.

- Franciotto Orsini (aged 48) [Romanus, but raised in Florence by Lorenzo the Magnificent], Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Cosmedin (died 1534) Archpriest of the Vatican Basilica. During the Conclave, and with the knowledge and consent of Cardinal Orsini, his relatives entered into an agreement to support Duke Francesco of Urbino and the French Interest, and to bind themselves to a position of hostility to Cardinal de' Medici [Molini, Documenti di storia italiana I, LXXII, pp. 139-142, at p. 141].

- Paolo Cesi (aged 40) [Romanus], son of Angelo Cesi, Conte di Manzano, a consistorial advocate and Apostolic secretary, and Francesca Cardoli of Narni. Cardinal Deacon of S. Nicola inter imagines. Administrator of the Diocese of Lund (1520-1521). (died 1537)

- Alessandro Cesarini (aged ?) [Romanus], son of Pier Paolo Cesarini and Giuliana Colonna. Cardinal Deacon of S. Sergio e Bacco, 1517-1523 (died 1542). He had been a personal friend of Giovanni de' Medici (Leo X). An Imperialist (Ghibbeline).

- Giovanni Salviati (aged 31) [Florence], Cardinal Deacon of S. Cosma e Damiano (died 1553). Uncle of Cosimo I, Grand Duke of Tuscany. Administrator of the diocese of Fermo (1518-1521).

- Nicolò Ridolfi (aged 20) [Florence], Cardinal Deacon of S. Vito e Modesto in Macello (1517). Nephew of Pope Leo X. Administrator of Orvieto (1520-1529). He died on January 31, 1550.

- Ercole Rangoni (aged ca. 30) [Modena], Cardinal Deacon of S. Agata de' Goti, 1517-1527 (died 1527) Bishop of Adria (1519-1524); Bishop of Modena (1520-1527).

- Agostino Trivulzio (aged ca. 36) [Mediolanensis], Cardinal Deacon of S. Adriano. Nephew of Cardinal Gianantonio Trivulzio. Protonotary Apostolic and Chamberlain of Julius II. Legatus a latere to the King of France for Leo X. Archbishop of Reggio Calabria (1520 and 1523-1529) (died in Rome on March 30, 1548)

- Francesco Pisano (aged 27) [Venice], of a senatorial family. At the request of Doge Leonardo Loredan, he was created Cardinal Deacon of S. Teodoro, 1518-1527. (died 1570)

Cardinals absent:

- François de Castelnau de Clermont de Lodève (aged 41), Auxitanus, Cardinal Priest of S. Stefano in Monte Celio (1509-1523) Archbishop of Narbonne (1502-1507) [Gallia christiana 6, 109-110], Archbishop of Auch (1507-1538) "Cardinal of Auch" Nephew of Cardinal Georges d' Amboise. In 1507 he was ambassador of Louis XII to Pope Julius II, and was excessively vigorous and free-speaking, as Protector of France. By order of Julius II he was arrested and placed in the Castel S. Angelo, when he attempted to return to France without papal permission. Under Clement VII, he obtained the post of Legate to Avignon. He died in 1541.

- Albert of Brandenburg (aged 31) Cardinal Priest of S. Pietro in Vincoli, formerly of S. Crisogono (1518-1521) (died 1545) Archbishop of Mainz. He wrote to the Emperor Charles V from Lochau on February 20, 1522 [Lanz, Correspondenz...Karl V I, no. xxxi, pp. 57-58].

- Eberhard von der Marck (aged 49), Cardinal Priest of S. Crisogono (died 1538) Bishop of Liège, Bishop of Chartres, Bishop of Valence.. Son of Robert I, Duke de Bouillon and Prince de Sedan

- Matthias Lang (aged 52 or 53), Cardinal Deacon of S. Angelo in Pescheria (died 1540) Bishop of Gurk, Bishop of Cartagena

- Thomas Wolsey (aged 50), Cardinal Priest of S. Cecilia (died 1530) Archbishop of York, (1514-1530), previously Bishop of Lincoln (1514), Bishop of Bath and Wells in commendam (1518-1521) [Le Neve Fasti ecclesiae anglicanae 1, 143], Bishop of Durham in commendam (1523-1529) [Le Neve, III, p. 298], Bishop of Winchester in commendam (1529). Chancellor of England (1515-1529) (died November 29, 1530).

- Louis de Bourbon Vendôme (aged 28), Cardinal Priest of S. Martino ai Monti (died 1557). Bishop of Laon (1510-1551)

-

Adrian Florenszoon Dedel (aged 62), Cardinal Priest of Ss. Giovanni e Paolo (died 1523). He was born March 2, 1459 in Utrecht. He was brought up at the expense of Margaret of York, Duchess of Burgundy and sister of King Edward IV of England. Doctor in Theology (Louvain). Emperor Maximilian appointed him to be tutor to the young Archduke Charles. Secretary of Archduke Charles and Privy Councillor. Provost of the Cathedral of Louvain. Dean of Louvain. Vice-Chancellor of the University. Ambassador to Ferdinand of Aragon (December, 1515), on the pretext of arranging a marriage between Charles and some French princess [Fleury Historia ecclesiastica 33, xciv, p. 129]. He was, however, scouting the situation in Spain and Ferdinand's state of health. Ferdinand, however, perceiving his real mission, refused to do business with him, but, to do him honor, made him Bishop of Tortosa (August 18, 1516). Ferdinand also requested the promotion of Adrian to the cardinalate from Leo X. When King Ferdinand of Aragon died on January 23, 1516, Cardinal Ximenes became Regent of Castile. This caused some trouble with Adrian, who presented a document signed by Charles which named Adrian as Regent of Castile. Ximenes had governed Castile in the King's name in the previous year when Ferdinand visited Aragon. Ximenes was named Regent of Castile in the Will of Ferdinand of Aragon, in the name of Ferdinand's daughter Joanna 'the Mad', but Ferdinand repudiated that Will shortly before his death, making a new Will in favor of Charles. Trouble was averted when the two agreed to sign documents jointly until Charles had attained his twentieth year, but Charles, after consultation, sent word that Ximenes should be Regent, and Adrian should be considered his Ambassador. Adrian was, after all, not a Spaniard, and Ximenes was. On July 1, 1517, Adrian was named a Cardinal, at the request of the Emperor Maximilian, and he was named Inquisitor General of Spain. Regent of Spain for Charles V. Ximenes died on November 8, 1517 [K. J. von Hefele, The Life and Times of Cardinal Ximenes (translated from the 2nd German edition by J. Dalton) (London 1885), 449-463].

- Alfonso of Portugal (aged 12), Cardinal, but promotion not effective until age 18 (died 1540) Archbishop of Lisbon and Evora, sixth child and fourth son of King Manuel I

- Jean de Lorraine (aged 23), son of René, Duke of Lorraine and pretender to the Kingdom of Sicily. Cardinal Deacon of S. Onofrio, 1519-1550. Bishop of Metz (1505-1547). He died on May 10, 1550. He had visited Rome, beginning on Wednesday, April 10, 1521 [Paris de Grassis, Il Diario di Leone X (ed. Armellini, 1884), p.83], but had returned home. Bishop of Toul (1517-1523); Bishop of Valence (1521-1550); BIshop of Verdun (1523-1544, admin.); Bishop of Luçon (1524- 1527, resigned); Albi (1536-1550); Lyon (1537-1539); Agen (1541-1550, admin.); Nantes (1542-1550); Gams (p. 293) calls him maximus cumulator episcopatuum.

There was another Cardinal, alive at the time of Pope Leo's death:

- Adriano di Castello (Castellesi) da Corneto, Cardinal Priest in the title of S. Crisogono. Bishop of Bath and Wells (1504-1518). He had participated in the conspiracy of Cardinal Petrucci [Pastor Lives of the Popes VII, 180-196]. He was excommunicated, deprived of all of his benefices, and deposed from Holy Orders, in Consistory on July 6, 1518 [Cassan, Lives of the Bishops of Bath and Wells, 331-346]. Marino Sanuto remarks in his Diaria that he was living privately in Venice in 1521, in the house of Jacobus Cadapesauro, Bishop of Paphos (1495-1541); on hearing of the death of Leo X, he set off for Rome, but disappeared. Sanuto reports the suggestion that he was waylaid and killed [Sanuto 32, p. 205; Gebhardt, 51-52; Brown, Calendar III, p. 191 no. 374; cf. Eubel III, p. 8 no. 43 and p. 62; Pastor VII, p. 196] Bartolomeo Angilellis remarks that some people said that on his deathbed, after his Confession, Pope Leo forgave Cardinal Adriano (perdonoe ad Adriano et che remesse) [Sanuto 32, p. 243; cf. Cartwright, On Papal Conclaves, pp. 135-136; William Maziere Brady, Anglo-Roman Papers (London: Alexander Gardner 1890), 11-29.].

Preliminaries

The General Congregations of the College of Cardinals took place at the palace of the Cardinal of Santa Croce, the Dean of the Sacred College (Luzio, 390). At the first Congregation held by the Cardinals after the Pope's death, on Monday, December 2, shortly after the body was transferred to the Basilica Vaticana, the Archbishop of Naples, Vincenzio Carafa, was appointed Governor of Rome, and a committee of Cardinals (Monte, Santi Quattro, Piccolomini, Armellino and Cesi) was elected to see to necessary arrangements for the State, the Church and the City. [Sanuto, 243]. On the second day there was a discussion of a proposal by Conte Baldassare Castiglione about the provision of 'quartirone'. At the fourth Congregation, Giovanni Mattheo, the secretary of Cardinal de' Medici, announced the Cardinal's departure from Milan on his way back to Rome for the Conclave. On the fifth day, Cardinal Soderini (Vulterano), who had just returned from exile thanks to the death of the pope, appeared and gave a speech exhorting the cardinals toward a good election 'ne inciderent in novam tirannidem' (by which, of course, he meant Cardinal de' Medici). Cardinal Cesarini made a reply in defense of Pope Leo "che quello non era stato tiranno". He was supported by Cardinal Salviati. On the sixth day, there was an exchange between Medici's secretary, Giovanni Mattheo, and Cardinal Soderini, who, having been absent at his first audience with the cardinals, complained of his authoritative remarks made without proper credentials. Mattheo replied in an indignant speech in defense of his cardinal and against Soderini's personal passion and odium [letter of Bernardo Rutha, December 19, 1521, the day after the conclusion of the novendiales; Luzio, 384-385]. The same enmity between Soderini and Medici is noticed by Peter Martyr (but cf. Henry Hallam, Introduction to the Literature of Europe I-II [1884] 322-323).

Giovanni Mattheo remarks that Leo X had left the papacy with a debt of 1,154,000 ducats. He also notes that the Imperial Orator, Don Juan Manuel, was working hard to ensure a victory for Cardinal de' Medici and was visiting each of the cardinals; he had the assistance of the Imperial cardinals, Santa Croce, Vic, Colonna, Valle, Giacobazzi and Campeggio. The imperial party appeared to have 26 votes, which, if true, was sufficient to elect. Ranged against him were the cardinals Fieschi, Ancona [Accolti], Monte, Grassis, Grimani, Volaterra, Como, Trivulzio, Cavaglione [Pallavicini] and Ivrea, and of course the French (Luzio, 385-386). He reports the news, however, that Cardinal Ivrea, Bonifazio Ferrera, had been captured and was being held at Pavia (Luzio, 387). In addition to that, the Camerlengo, Cardinal Armellini de' Medici, and Cardinal Cibo were quarreling about Armellino's purchase of the office of Camerlengo from Cibo in August, and whether the purchase was valid or simoniacal, and whether Cibo ought not to be Camerlengo now for the Sede Vacante [Luzio 389-390]. Ambassador Juan Manuel, however, writing to the Emperor Charles on Christmas Eve, reported that the cardinals who were ready to support the Imperial cause were: Vich, Valle, Siena, Jacobacci, Campegio, de' Medici, Sion, Santi Quatro, and Farnese. He also thought that Cesarini and Santa Croce would do their duty. But Ancona and Volterra were his enemies, and among the suspicious were Fieschi, Monte, Grassis and Minerva. Mantua was uncertain. [Bergenroth, p. 385 no. 370]. Cardinal Farnese was the most uncertain of all, since he was suspected of being favorable to French interests. To secure his compliance, he was required to offer his second son as a hostage for his correct behavior; he delivered his son to the Imperial agents, and the son was whisked off to Naples [Bergenroth, p. 386, no. 371].

The Cardinals had planned to enter Conclave on December 18, after the conclusion of the Novendiales. But when the news arrived that the Cardinal of Ivrea, Bonifacio Ferrero, had been detained at Pavia by Spanish troops, the Cardinals decided to wait eight days for him and for the arrival of the French, tentatively fixing a new date of the 26th for the opening of the Conclave [letter of Alvise Gradenigo, Venetian Orator, dated December 18, 1521: Sanuto, 273; letter of Count Giorgio di Zaffo of December 18, in Sanuto, 274; letter of Juan Manuel the Imperial Ambassador in Bergenroth, p. 384, no. 389]. Apparently the Cardinals also addressed a letter to Pavia, demanding the release of Ivrea.

On Saturday, December 21, a Congregation took place at the Dean's residence as usual. The Imperial agent Lutrech made a protest against the activities of the French agent de Granges, who was trying to recover property in Lombardia using the Church and some papal troops as his tool, and during a Sede Vacante.

On Sunday the 22nd, the usual meeting took place at the Dean's residence, with everyone present (according to the Burmann narrative) except Grimani, Gonzaga and Cibo. After lunch, several cardinals (li rmi carli vechi) who were opposed to Cardinal de' Medici had met at the residence of Cardinal Colonna: Giacobazzi, Monte, Grassis, Piccolomini, Minerva, Trani, Ancona, Cornaro, Pisano, Trivulzio, Como, Vic, Ponzetta and Colonna. Grimani, who was not present, sent his nephew, as did Fieschi, Cavaglione and Santa Croce. They decided that they wanted a pope who was over fifty years of age and not Medici. Another meeting was scheduled for Christmas Eve. It was noticed in the evening of Christmas Eve that Cardinal de' Medici looked pale and much afflicted [Luzio, 392-394].

Cardinal Wolsey's Candidacy

In a letter of Thursday, December 19, 1521, Bishop Bernard de Mezza, the Ambassador of Charles V in England, reported on a conversation he had had with King Henry VIII and Cardinal Wolsey on the 16th at Richmond. Henry was anxious to promote the candidacy of Wolsey, but hesitant to do so without the cooperation of Charles and with care to be taken not to offend Cardinal de' Medici, who was the leading candidate [Bradford, 14-20]:

...si non esset apparens possibilitas quod electio dicti Cardinalis Eboracensis sortiretur effectam, visum est providere pro tali casu taliter quod ad minus si supradictus non deberet eligi, eligatur Cardinalis de Medicis ne perdatur ille amicus, nec sentiat dictus Cardinalis de Medicis quod aliquid faciunt Majestates vestrae in prejudicium electionis suae ymo quod omnia fiunt in favorem suam nisi in casu quod dictus de Medicis nullam haberet spem neque copiam votorum pro se, tunc aperte esset agendum pro dicto Reverendissimo Cardinali Eboracensi....

Wolsey, in fact, had sworn in the Bishop's presence that nothing could induce him to seek or accept the Papacy, unless both the King and the Emperor deemed it conducive to the security and glory of both of them. This was, of course, insincere posturing, not uncommon among papabili and would-be papabili. But it also had the serious purpose of getting both King and Emperor to commit to the election of Wolsey. Bishop de Mezza did not believe that Wolsey had any confidence of succeeding in getting elected, but he did believe that Wolsey thought that there was some profit that he could derive from carrying forward the design. Mezza's advice to the Emperor was to be agreeable to Wolsey's candidacy, not expecting him to succeed, but expecting to keep Wolsey favorable to and trusting of the Emperor. The Emperor Charles V had twice promised his assistance to Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, as he indicated himself in a letter to Ambassador de Mezza, written from Ghent on the 14th of December, which crossed de Mezza's in the mail [Bradford, 21-25]:

D'aultre part vous direz de par nous à Monseigneur le Legat, comme nous avons toujours en notre bonne souvenance son avancement et exaltation, et le tenons racors de propos, que luy avons tenuz à Bruges touchant la Papalité, ensuivant lesquels et pour l'effect de ce, sommes deliberez l'ayder de notre pouvoir, tant en cestuy affaire que aultres, que luy pourroient toucher, parquoy le requerez qu'il vueille dire son advis, s'il y a quelque affection, et nous y employerons trés voluntier sans y riens espaargner...

Henry was particulary worried lest a partisan of the French should be elected. Wolsey told Bishop Mezza that King François had offered him the French votes in the Conclave (some twenty-two, he claimed), but Wolsey assured Mezza that he was counting rather on the support of Charles V [Bradford, Correspondence of the Emperor Charles V., p. 27].

Wolsey did not attend the conclave—a mistake for a would-be candidate. But not a mistake for a minister whose prime purpose was to keep France and the Empire from a rapprochement.

Charles V had in fact seems to have instructed his representative in Rome, Don Juan Manuel, to support the cause of Cardinal de' Medici, not that of Wolsey. A letter of January 17, 1522 from de Mezza in England to the Emperor Charles indicates that Wolsey was very angry, having heard of the Spanish Ambassador's dealings at the Conclave [Bradford, 33]. His anger does not, of course, validate the notion that he expected to become pope. He had knowingly made choices which virtually ensured that he would not succeed to the papal throne. And, in part due to his diplomatic skills, he was trusted neither by the Emperor nor by the King of France.

Henry VIII had sent a special ambassador to Rome, his secretary Richard Pace [Brown, Calendar of State Papers...Venice 3, no. 384, p. 197], who arrived after the election had already taken place [Gachard, xiv-xvi]. Pace had experience in electioneering; he had also been present at the Election of Charles V as Holy Roman Emperor, and reported on the business to Cardinal Wolsey on July 27, 1519 [H. Ellis, Original Letters illustrative of English History Vol I, second edition (London 1825), pp. 156-158, no. lvi]. On December 23, Pace was in Ghent [Brown, Calendar, p. 379]. On January 8, the day before the election of Adrian Dedel, he had only reached Trent [Sanuto 32, p. 267]. Wolsey received six or seven votes on the fifth scrutiny, and that was all [Sanuto, 385; Bergenroth, 391]. John Clerk, the English ambassador, wrote to Wolsey (Ellis, 307) that Wolsey had received 9 votes in the first scrutiny, 12 in the second, and 19 in the third. This was a lie. To placate his master, Clerk remarks that some cardinals believed Wolsey too young [ignoring the candidacy of Cibò, who was only thirty, and the votes for Albert of Brandenburg, who was only thirty-one]; that he was determined to the execution of truth and justice; and "thirdly, that ye favored not all the best th' Emperor". Clerk was being diplomatic, inventing rationalizations and numbers to assuage Wolsey's ego, or perhaps borrowing numbers from Cardinal Campeggio, who also wrote to Wolsey about the votes given him [Brewer, ccv; Taunton, 144-145]. After the Conclave was over, on January 11, 1522, the Imperial Ambassador, Juan Manuel, requested that the Emperor write courteous letters of thanks to Cardinal de' Medici, Cardinal Valle, and Cardinal Campeggio, who had rendered him signal services [Bergenroth, p. 393 no. 376].

Other Hopefuls

Other cardinals under consideration were Franciotto Orsini, the French candidate (whose votes fluctuated between 3 and 7), and Cardinal Adrian of Utrecht, bishop of Tortosa in Spain, who was not even present at the conclave, since he was serving as principal minister of the Emperor Charles V in Spain. Combatting the Lutheran heresy and schism was a primary consideration for the cardinals, for which the active cooperation of the Emperor was essential, and the Emperor had confidence in Cardinal Adrian, his boyhood tutor who had been co-regent in Spain (1517-1519) until Charles assumed his powers. Reformers on both sides were demanding a church council, but the Emperor Charles was determined that it should meet in a place convienient to his supporters and that it should exclude the protestants from participating. Despite his promises to Wolsey, the Emperor's real candidate was Cardinal Adrian, though this was supposed to be a deep dark "secret". That, at any rate, it what Cardinal de' Medici and his faction were believed to have planned with the Emperor, but Medici and the deeply laid plan were disbelieved by John Clerk in his report to Cardinal Wolsey [Ellis, 308-309].

In a letter of Sunday, December 15, the Venetian ambassador reported that Cardinal Grimani had good hopes of becoming pope, but, he adds, so did Cardinal de' Medici, though the Cardinal of Volterra (Francesco Soderini) was campaigning against him [Sanuto, 260]; Soderini's family had lost a power struggle in Florence to the Medici, and carried a grudge. Since Medici was a supporter of the Imperial faction, Soderini was found in the French faction. In a letter of the 14th, the Venetian ambassador lists as adherents of Medici the Cardinals Santi Quattro (Lorenzo Pucci), Armellino, Cortona, Cibo, Salviati, Ridolfi, Rangone. Sedunense (Scheiner), Cexis (Cesi), Santa Croce (Carvajal), Vico (Raimundo de Vich), Colonna, Orsini, Aracoeli (Cristoforo Numai), Mantua (Sigismondo Gonzaga), Cornaro, Pisani, Ponzeto, Trani (de Cupis), Petruzzo and Cesarini. (Sanuto, 263). On the 18th he wrote again that Medici was not in as great a favor as before (Sanuto, 273). On the 20th the ambassador reported that Colonna had deserted Medici, and that the Imperial agent, Msgr. von Lutrech, was remarking that Leo X had been an annoyance to the Emperor in the conflict with France over the Duchy of Milan [Sanuto, 284]. Count Baldassare Castiglione, who was the Ambassador of the Marquis of Mantua in Rome, reported to Marchese Federico on December 22 [Serassi 3],

Le pratiche sono strettissime, e benchè Mons. Rev. de' Medici abbia de' voti, pure se gli sono scoperti ancora molti nemici di modo che non so come anderanno le cose sue.

In his report of Tuesday, December 31 [Serassi, 4], however, he remarks:

e in quest' ora universalmente Monsig. Rev. Farnese è in maggior opinione che alcuno alter che sia, e stimasi il Pontificato abbia a succeder in lui.

On Saturday, December 28, Juan Manuel, the Imperial Ambassador in Rome, wrote to the Emperor [Bergenroth, pp. 385-386 no. 371] that he had arranged with Cardinal de’ Medici that, if he saw that his own election was impossible, he would give his vote and the votes of his followers to certain candidates who were good Imperialists. Farnese was on the list, but at the very bottom, due to suspicions of his French leanings. If a cardinal outside the Conclave were to be considered, the Ambassador suggested to Medici the name of Adrian Dedel, Bishop of Tortosa. Manuel also reported that he had provisionally decided not to be in the Vatican Palace personally, but instead to send agents: Ascanio Colonna, Juan de Laoysa, and Willem Enckenvoirt.

Opening of the Conclave

There were forty-eight cardinals at the time of the pope's death. Cardinal Ferrero (Ivrea) was detained at Pavia by Duke Francesco Sforza of Milan, but did finally reach Rome by the time the Conclave began; three other French cardinals did not even attempt the perilous journey. Nonetheless, Cardinal Trivulzio was passing around a letter from the Cardinal Jean de Lorraine, intimating that the French contingent would arrive by January 5, and begging the cardinals to wait for their arrival [Sanuto, 325, a letter from the Venetian Ambassador, Alviso Gradenigo, of January 2, 1522]. On Friday, December 27, 1521, Cardinal Colonna sang the Mass of the Holy Spirit, with thirty-seven cardinals in attendance. The oration pro pontifice eligendo was pronounced by Msgr. Vincentio Pimpinella. Thereafter some of the cardinals proceeded to the Conclave area, others returned home. In the evening, thirty-nine of the cardinals entered conclave, Cardinals Cibo and Grimani being carried in on litters in the evening (full but inaccurate list of living cardinals, ten being absent, a total of fifty: Sanuto, 326-329). Three conclavists were allowed to each cardinal. The pope-makers at the conclave were Cardinal Giulio de' Medici, the Vice-Chancellor, who had been his cousin Leo's chief minister, and the Dominican Cardinal Tommaso de Vio Cajetan (Caetani). A complete tally sheet of the votes given in the eleven scrutinies is preserved by Marino Sanuto in his Diary. There is another in Ms. Vaticanus Latinus 3920, 33-41verso: Scrutinia aliquot per R.mos Dnos Car.les in Conclavi celebrata in electione R. Adriani Dertueñ [V. Forcella, Catalogo dei manoscritti relativi alla storia di Roma I (Roma 1879), p. 33 no. 109].

Balloting

On Sunday, December 29, the Cardinals met in Congregation. The first business was to inquire of the Cardinals whether they wished to proceed by open or by secret ballot. Twenty-four cardinals voted for secret ballots, thirteen for open, and two abstentions [Gattico, 318; Burmann, p. 147].

The Mass on Monday the 30th was celebrated by Cardinal Carvajal in the Chapel of Pope Nicholas. The first business on Monday, December 30, was to inquire of the Cardinals whether they wished to proceed to an accessio after the scrutiny. The decision was that there would be no accessio after the first scrutiny, but that it would take place after each succeeding scrutiny [Gattico, 318]. In the first scrutiny, on Monday, December 30 (according to the Venetian ambassador Gradenigo; Sanuto, 325), Cardinal de'Medici received the most votes [not true], Cardinal Flisco (Fieschi) came second, and Farnese third [not true]. The Ambassador of Florence, Galeazzo de' Medici, reported that Fieschi had received 12 votes [He actually received 10], Grimani 10, Carvajal (Ostia) 10 [He actually received 9], Jacobacci 7, Grassi 6, Accolti 5, Monti 5, Soderini (Volterra) 5, and Farnese "a few" [2 in fact], with other scattered votes (Petruccelli, 519). The Burmann narrative gives the following figures for the first scrutiny (emending Ostia's IV to IX, a simple transcriptional error), almost exactly the same as the Simancas narrative [It should be noted that the Simancas narrative gives only the results of the Scrutiny, without including additions from the Accessio]:

| Cardinal | votes |

|---|---|

| Carvajal (Ostia) | 9 |

| Grimani | 10 |

| Soderini (Volterra) | 5 |

| Fieschi | 10 |

| Monte | 5 |

| Accolti (Ancona) | 5 |

| de Grassis | 6 |

| Jacobacci | 7 |

| Medicis | 3 |

| Others had fewer than 3 votes | |

Grimani's nephew was putting it about that his uncle had received 22 votes; a detailed list of the results of the scrutinies gives him no more than ten votes at any time, and it is hard to see where his dozen other votes on the accession would have come from, except from the French faction, with which Venice was cooperating. It must also be remembered that the vote was in the nature of a preference poll, hence the much larger totals in each Scrutiny than the 37-39 cardinals present at the Conclave. A cardinal could vote for more than one candidate. If some or many of Grimani's votes on the scrutiny were second-choice or third-choice votes, he might be very far indeed from the Throne of Peter. And in any case, 22 was not 25, the number needed to elect. at the beginning of the conclave. Grimani's nephew was engaging in pratticà. No doubt others were doing the same, which contributed to the widely differing numbers of votes reported by the various sources. John Clerk's numbers are similarly wild: Wolsey did not receive nine votes on the First Scrutiny, or twelve on the Second Scrutiny. The Simancas document [Bergenroth p. 390] gives the following tally for the first and second scrutiny (omitting any mention of Cardinal Farnese!):

| Cardinal | votes |

|---|---|

| Carvajal (Ostia) | 9 |

| Grimani | 10 |

| Soderini (Volterra) | 5 |

| Fieschi | 10 |

| Monte | 5 |

| Accolti (Ancona) | 6 |

| de Grassis | 6 |

| Jacobacci | 7 |

| Medicis | 3 |

| Others had fewer than 3 votes | |

Also on the 30th, de sero there was another Congregation in which Electoral Capitulations were discussed [Gattico, 318]. On the 30th, during the night between Monday and Tuesday, Grimani was removed from the conclave (Sanuto, 325), apparently having had an accident. He had still not returned by the 2nd [Sanuto, 356]. Count Baldassare Castiglione was one of the guardians of the Conclave, and was present at the exit of Cardinal Grimani (Serassi, 4-5; translated by J. Cartwright, 138-139):

Today a thing has happened which has very seldom been known before. The doors of the conclave were opened with great ceremony and respect. The Cardinals all came to the doors and knocked, telling the Bishops that Mons. Grimani was in danger of death, and praying them to open the doors. Accordingly, the ambassadors were summoned, and the Portuguese and I being the only envoys present, the doors were opened, and we saw all the Cardinals with torches in their hands, for the place was very dark. Then Mons. Santa Croce [Carvajal], as Dean of the College, told us the Mons. Grimani was in peril of death, as the doctors swore, and begged the ambassadors to inform their princes that for this reason the doors had been opened, and for no other. Mons.di Como [Trivulzio] said the same, and so Mons. Grimani was carried out in a chair, and the doors were walled up again. I fear that His Reverence will die all the same, for he looks very ill. Perhaps tomorrow we shall hear who is Pope.

That was the end of Cardinal Grimani's march to the Papacy. After the second ballot, he received no votes.

In the second scrutiny, on Tuesday, December 31, the Florentine Ambassador reported [Petruccelli, 519-520], Farnese had 17 votes [this must include the accessio], Medici 16, and Fieschi 8, with other votes scattered. The authority of the Simancas document comes into question, seeing that it does not mention Cardinal Farnese at all.

Msgr. Blasius de Martinelli, the Papal Master of Ceremonies—who has a good deal more authority than any of the other sources—says that the discussion about the departure of Cardinal Grimani took place on December 31, not December 30, at a Congregation de sero. Grimani had actually had himself carried as far as the Sistine Chapel when the Cardinals caught up with him and begged him not to attempt to leave the Conclave. In reply he claimed that he was in danger of death. The Cardinals summoned the Conclave doctors and Grimani's personal physicians and demanded on oath a statement of Grimani's condition. The Cardinals, including Cardinal Cibo, then accompanied Grimani to the gate of the Conclave, in the company of most of the Conclave officials, including Paris de Grassis, the retired Bishop of Pesauro [Gattico, 318-319]. We prefer to follow Biagio di Martinelli da Cesena and put Grimani's departure on the evening of the 31st, after the Second Scrutiny and second accession, in which he failed to be elected pope.

On Wednesday, January 1, 1522, the Simancas document reports the results of the Third Scrutiny as follows:

| Cardinal | votes |

|---|---|

| Carvajal (Ostia) | 10 |

| Fieschi | 7 |

| Scheiner | 7 |

| Trivulzio (Como) | 7 |

| Jacobacci | 7 |

| Orsini | 7 |

| Monte | 6 |

| Ponzetta | 6 |

| Accolti (Ancona) | 5 |

| Medicis | 5 |

| De Cupis (Trani) | 5 |

| Numai (Aracoeli) | 5 |

| Cornaro (Cornelio) | 5 |

| Others had fewer than 5 votes | |

Grimani and Soderini had evidently been dropped from consideration. Burmann's narrative [p. 148] remarks that one of the ballots contained thirteen names. This annoyed a number of the cardinals, and they demanded that the ballot be opened, which was not agreed to. The other ballots contained between one and five names.

On Thursday, January 2, at the Fourth Scrutiny, according to the Simancas document,

| Cardinal | votes |

|---|---|

| Pucci (IV Sanctorum) | 14 |

| Carvajal (Ostia) | 8 |

| Accolti (Ancona) | 8 |

| Fieschi | 7 |

| Jacobacci | 7 |

| Cajetan (S. Sisto) | 7 |

| Scheiner (Sion) | 6 |

| (Valencia) | 6 |

| Numai (Aracoeli) | 6 |

| Gonzaga (Mantua) | 6 |

| Monte | 5 |

| Orsini | 5 |

| Soderini (Volterra) | 4 |

| Grassi (Bologna) | 5 |

| Medici | 4 |

| Campeggio | 4 |

| Egidio | 4 |

| Others had fewer than 4 votes | |

On Friday, January 3 [though the statistics accord more closely with the Simancas document's report for January 2], Lorenzo Pucci had 14 votes, Fieschi 7, Jacobazzi 7, Vio (San Sisto) 7, Scheiner 6, Raimondo de Vich 6, Numai (Aracoeli) 6, Monti 5, Ursino 5, Accolti (San Eusebio) 5, Orsini 5, Soderini 4, Grassi 4, Medici 4, Campeggio 4, Egidio Canisio 4 (Petruccelli, 520). At the scrutiny, Cardinal Cibo, who was confined to his bed, attempted to send in his vote by the hand of Cardinal Orsini, but this was objected to by the Cardinals, and instead they sent Cardinal Accolti and Cardinal Orsini accompanied by Paris de Grassis and the Master of Ceremonies Ippolito Morbiolo, who obtained the ballot and then swore to the Cardinals that it had been executed by Cardinal Cibo personally. The same method was followed at each subsequent scrutiny. [Gattico, 319].

Another source, a conclave diarist, reported that on January 3 the Cardinal Priest of SS. Giovanni e Paolo, Adrian of Utrecht, had eight votes [Laemmer, 11]. This is reported by the Simancas document as well, which also gives Cardinal Wolsey seven votes. It may be that letters from the Emperor had finally arrived, and that the signal had been given by Ambassador Juan Manuel to fulfil in the most literal sense the committment to support Wolsey. Hence his seven votes. But obviously many Imperialists were not prepared to follow. Four still supported Cardinal de' Medici, and others (probably following Medici himself) switched to Dedel. It may also be noted that Wolsey's 'support' dropped to zero after that scrutiny.

| Cardinal | votes |

|---|---|

| Soderini (Volterra) | 12 |

| Fieschi | 9 |

| Adrian Dedel (Tortosa) | 8 |

| Monte | 7 |

| Accolti (Ancona) | 7 |

| Wolsey (York) | 7 |

| Jacobacci | 7 |

| Carvajal (Ostia) | 6 |

| Medici | 6 |

| Valle | 6 |

| Egidio | 6 |

| Others had fewer than 6 votes | |

.As of this point, it is apparent, the cardinals had not settled down to serious negotiation, and there was no factional discipline. As Paolo Giovio put it [Vita Hadriani Sexti, cap. viii]:

neminem posse Pontificem creari, qui Junioribus et Julio minime placuisset; quoniam ex ordine Seniorum nemo reperiebatur, qui se eo honore non dignum putaret, et id studio et praecipiti liberalitate alteri vel amicissimo concedere vellet, quod privato ipsius merito, aut aetati in aliena praesertim altercatione facile tribui posse videretur.

No one could be elected who was not acceptable to Medici and the Medicean cardinals. At the same time, nearly each one of the Seniors thought that he was papabile, and was reluctant to give in, even to a close friend, whatever his merit. The Seniors, after all, in the belief in their own superiority to the Juniors, had sworn not to cast their votes for anyone who was not a member of their faction [Giovio, Vita Hadriani Sexti, viii; vita Pompei Columnae card.].

Sed unum et certum Senioribus, detestabili consilio conjuratis, decretum erat, nemini nisi ex ipso sui corporis ordine suffragari, quod aetatis honore, et opinione virtutis Junioribus praestare viderentur.

At iuniorum globus fide constantiaque firmissimus (suffragiis scilicet miro consensu ad unius arbitrium revocatis) nullis omnino artibus aut machinis disiici labefactarique poterat. Ob id praeclare omnes intelligebant, neminem quem non probaret Iulius, bis tertiam suffragiorum partem, uti ex lege opus esset, esse consecuturum.

The difficulty for some of these Seniors, however, was that they were also members of the Imperialist faction, and they might have to make a choice. There was a Congregation de sero to complete the Electoral Capitulations and obtain the signatures [Gattico, 319].

On the 4th and 5th there was no substantial change. The Simancas document reports the votes at the Sixth Scrutiny on January 4, 1522, as follows:

| Cardinal | votes |

|---|---|

| Carvajal (Ostia) | 9 |

| Fieschi | 9 |

| Scheiner | 8 |

| Pucci (IV Sanctorum) | 8 |

| Jacobacci | 8 |

| Numai (Aracoeli) | 8 |

| Accolti (Ancona) | 7 |

| Valle | 7 |

| Campeggio | 7 |

| Orsini | 7 |

| Others had fewer than 7 votes | |

On Sunday, January 5, at the Seventh Scrutiny, the Simancas document reports the votes as:

| Cardinal | votes |

|---|---|

| Fieschi | 9 |

| Scheiner | 8 |

| Pucci (IV Sanctorum) | 8 |

| Vich | 7 |

| Carvajal (Ostia) | 6 |

| Accolti (Ancona) | 6 |

| Grassis (Bologna) | 6 |

| Medici | 6 |

| Jacobacci | 6 |

| Others had fewer than 6 votes | |

Cibo's Moment

On Monday, the 6th of January, some terrible confusion ensued. Several cardinals were ill, including Farnese and Cibo. Farnese sent in his vote. The Scrutators Accolti and Orsini were sent to collect Cibo's vote. Meantime Farnese had a conversation with Cardinal Cesarini and decided to change his vote. Cardinal Pucci, thinking that some coup was afoot, cried out, habemus papam! and acceded to Cardinal Cibo. Medici and his adherents followed Pucci: Petruccio, Valenza, Campeggio, Cortona and d' Aragona also announced for Cibo, who was, after all, a member of their faction. He was also a favorite of the "younger cardinals" (He himself was only 31) and those with a taste for the humanism and luxury of the reign of Leo X. Cardinal Cesarini attempted to accede to Cibo as well, but without renouncing the vote he had given in the scrutiny to Farnese. This maneuvre produced sharp disagreement, and in the end Cibo did not receive sufficient votes with the accessio to elect (He had 20, and needed 26). In any event, there were serious reformers among the cardinals, who were looking for a pope who would deal with the problems posed by the Lutheran menace and the growing tensions between the Empire and France, and who would never vote for a pleasure-loving lightweight.

The Simancas document [Bergenroth, p. 392] knows nothing of these events, and indicates instead that Cardinal Farnese had received 12 votes [2 according to Sanuto's tally sheet]. At that point the accessio brought him in addition Medici, Petrucci, Valle, Campeggio, Cortona, Armellino and Rangone—a total of nineteen. Cardinal Cesarini, however, withdrew his original vote for Farnese and switched to Cardinal Egidio. Farnese's march to the Throne of Peter was thwarted. He was, however, six votes short of election, and it is hard to see where they would have come from. The Simancas document indicates that it was after this debacle that Cardinal Grimani withdrew from the Conclave—which is in contradiction to the report (above) of Baldasarre Castiglione, one of the guardians of the Conclave, that he had left the Conclave during the night of December 30. It also alleges that Cardinal Egidio, who had once been Cardinal Farnese's confessor, went from cardinal to cardinal telling very bad stories about Farnese. The implication that Egidio was breaking the seal of confession is absurd, as is the idea that he had to whisper about the very well known moral failings of Cardinal Farnese. The Simancas document may, however, be read as to give evidence that Cardinal Grimani was back in the Conclave and participating on January 6.

On the day after the conclusion of the Conclave, January 10, 1522, the caudatario of the Vicar-General of the Archdiocese of Florence, Giovanni Maria Galiani, wrote up his version of the event (Staffetti 35-36 n.1):

... Hadriano ... stato creato da Monsignor nostro Reverendissimo [Giulio de' Medici] contra l' opinione delli coniurati nostri adversarii, a la qual creatione ce sono iti gabati. Monsignor nostro lo ha voluto fare perchè questi arabiati non si sono mai possuti accordare etiam in favor d' uno de' lori, anchor che più d'uno glie n' habi preposti: non possendo obtenere Farnese li propose La Valle, qui etiam exclusus fuit et molti altri. Et il Reverendissimo Cybo a poco a poco si acostò, che maladetto fusse quel poco: li agenti soi Conclavisti andorno a diversi de' cardinali della conventicula et exponendoli come il prefato Reverendissimo Cibo era agravato de infermità, ad suplevarlo li pregavano darli el voto ad ciò se recreasse, et l' uno non sapendo de l' altro promisero, come poi quando furno per poner li voti si scoperse che l' Ursino, ragionando cum Sa(n)cti Quattro et dicendo–Dio Volesse–s' imbatete per mala sorte passar Colunna, qual intese le parole: Dio volesse, et entrato in suspetto, trovò de soi ciascuno et l' interrogava a chi haveano dato el voto; l' uno respondeva a Cibo et l' altro similmente non sapendo più oltra, in modo che veduto erano dodici voti dei soi per Cibo et quindici sapeva h' haveva il Reverendissimo nostro fermi, fece che molti cassorno Cibo et poseno de l' altri, et così la cosa fa scoperta; per il che è piaciunto poi a l' altissimo che sia electo questo sancto homo, qual credemo sarà frutifero per la sua santa Chiesa et per la fede christiana.

The next two scrutinies after the Cibo fiasco produced no progress.

At the Ninth Scrutiny on January 7, 1522, the votes were [Bergenroth, p. 392]:

| Cardinal | votes |

|---|---|

| Grimani | 10 |

| Fieschi | 10 |

| Carvajal (Ostia) | 9 |

| Piccolomini | 8 |

| Jacobacci | 8 |

| Campeggio | 7 |

| Orsini | 7 |

At the Tenth Scrutiny on Wednesday, January 8, 1522, the votes were [Bergenroth, p. 392]:

| Cardinal | votes |

|---|---|

| Jacobacci | 11 |

| Carvajal (Ostia) | 10 |

| Fieschi | 10 |

| Piccolomini | 10 |

| Grimani | 7 |

On January 8, Cardinal Carvajal (Santa Croce) received 20 votes, as did Fieschi; Jacobazzi had 12, and Farnese 4—according to other reports (which obviously included the votes from the accessio). It was reported in a letter of January 8 by Count Giorgio del Zaffo in Rome [Sanuto 32, 356] that Cardinal Grimani was better and expected to return to the Conclave. Biagio da Cesena, the Master of Ceremonies reported [Gattico, 320] that Cardinal de Medici and Cardinal Colonna had come to an agreement that they would make Cardinal Andrea della Valle pope. But when Medici, who did not want to be deceived as to where people stood, asked about their choice, the deal fell apart.

Though Medici may have controlled about fifteen votes, he was well aware that he himself could not be elected. King François I is said to have remarked that if Medici were elected, neither he nor any man in his kingdom would obey the Church of Rome [J.S. Brewer (ed.) Letters and Papers, foreign and domestic, of the Reign of Henry VIII Vol. III. Part II, no. 1947 (Sir William Fitzwilliam to Cardinal Wolsey)]. This was a clear threat at schism, and (as some argue) the first attempt to impose an exclusiva against a candidate in a Conclave.

The Emperor had other candidates. It is said that Medici therefore threw his influence behind Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, who was then able to command twenty-two votes, four short of election. This is more or less confirmed by John Clerk, the English ambassador [Ellis, 306-307]: "After that there_____ scrutynie made day by day, two or thre days together, but the said Cardinal de Farnesio coude neuer passe xxijth voices..." Apparently a 'virtual veto' was being exercised. And that was the end of Farnese's candidacy, according to the story of Clerk. As with the candidacy of Wolsey, however, Clerk's numbers are completely at variance with the statistics provided by Sanuto and by the Simancas document, as well as with Juan Manuel's report to the Emperor that Farnese was the least desirable of the acceptable candidates, since he was suspected of French leanings. It is better to disregard this entire episode as extra-conclave gossip.

It was perhaps at this junction that the important conversation reported by Paolo Giovio [Vita Hadriani VI, cap. viii] took place. The Seniors, frustrated at the lack of movement toward any of their candidates, sent two representatives, Cardinal Ciocchi del Monte and Cardinal Tommaso de Vio (Cajetanus) to speak with Medici.

The Emperor's Candidate

The Venetian Ambassador wrote to his government on the 10th of January (Sanuto, 377-378) that there were eleven scrutinies during the conclave, and on Thursday, January 9, in the last, Cardinal Adrian of Tortosa had 15 votes. According to an anonymous conclavist, "Ostiensis et Dertsensis habuerunt vota XV" (Carvajal and Adrian had fifteen votes each) [Laemmer, 11]. The Simancas document agrees. Fifteen votes for Cardinal Carvajal certainly came from the Seniores; the fifteen for Adrian Dedel came from the Imperialists, led by Medici. The eleven votes for Scheiner also came from Imperialists.

At that point Cardinal Tommaso de Vio (Cajetan), Cardinal of S. Sisto, finally revealed the secret that he had been carrying, the name of the person who was the choice of the Emperor Charles [Petruccelli, 523-524], after the failure of Medici's candidacy, of course. Vio made a dramatic speech to the cardinals in favor of Adrian Florensz Dedel. Cardinal del Monte, however, was dubious (according to the Simancas document [Bergenroth, p. 392 no. 375]), and Cardinal de Grassis stated that he could not support the Cardinal of Tortosa, who had never been to Rome and whom he did not know. At the accessio, however, Cardinal Adrian Dedel obtained a total of 28 votes, which was sufficient to elect (Relazioni 74). The principal provider of votes was, of course, Cardinal de' Medici, who presided over the Imperial faction. Those who voted for Adrian at the accessio included: Caetano, Colonna, Cavaglione (Pallavicino, Bishop of Cavaillon), Monte (Antonio Ciocchi del Monte), Trivulzio, Piccolomini, Aracoeli (Numai), Ancona (Pietro de Accolti), Campeggio, Armellino, Trani, Jacobazzi and Como (Trivulzi). The rest agreed to support the choice of the two-thirds majority. But Cardinal Carvajal, who had the third-largest number of actual votes, held out for some time with his vote for Cardinal del Monte; finally, however, he gave in and the result was unanimous. The total number of cardinals voting at the final scrutiny was thirty-nine [Eubel III, p. 18 n. 1, from the Acta Consistorialia]: 1522 Jan. 9, die Iovis, Adrianus tt. ss. Iohannis et Pauli pbr. card. Dertusensis electus fuit a 39 cardinalibus in summum pontifice, ipso absente dum regnorum Castellae et Legionis pro Carolo rege Hispaniae gubernaculum ageret. A putative list of the votes in all of the eleven scrutinies is given in a letter to Giustinian Contarini from Count Giorgio di Zafo (Sanuto, 384-385). In his list (of unknown provenance) the largest number of votes obtained by anyone at any time was 21 garnered by Cardinal Farnese on the 8th scrutiny.

On January 9, 1522, at 13:00 hours, the election of Cardinal Adrianus Dedel was made public by Cardinal Cornaro, the senior Cardinal Deacon, and the Conclave was opened. In a letter written on May 3, while he was still in Spain at Zaragossa, Adrian VI acknowledged the importance of Charles V's support and the work of Don Juan Manuel in his election [William Bradford, Correspondence of the Emperor Charles V. and his ambassadors at the Courts of England and France (London: Richard Bentley, 1850), 41-45]:

...savoie aussi que icelle mon election vous donneroit quelque tristesse et desplaisance pour le detriment à venir èschoses de pardeça, à cause de mon absence; mais l'excessive et vehemente delectation survenue en chassera et expulsers toute tristesse non seulement contraire, mais aussi toute aultre quelconque, je croy bien toutefois que icontemplacion de votre Majestè, comme le Sacré collège des Cardinaulx doibt avoir dit à Don Jehan Manuel, j’aye éste esteut, sachantz iceulx Cardinaulx moy estre aggreable à votre Majesté et jamais n’eussent osé eslire homme mal aggreable, et à vous et au Roy dé France...

On January 10, it was decided that, until the new pope should arrive, each month three cardinals (one from each of the Orders) should givern and remain in the Apostolic Palace.

On January 11, the Imperial Ambassador, Juan Manuel, wrote to the Emperor that Cardinal de' Medici had behaved well in the Conclave, and that it was highly desirable to preserve the good will between the Cardinal and the Emperor. The Papal States were being harassed by the French and the Venetians, and it was essential that Florence not fall under French influence. Juan Manuel begged the Emperor to grant Cardinal de' Medici a pension of 10,000 ducats. He indicated that Legates were being dispatched to the Pope-elect in Spain (Cesarini and Colonna), but warned that the new pope should come to Italy by sea, and on no account by land through France. He should be kept away from any opportunity for the French to exert their influence over him [Bergenroth, p. 393 no. 376].

On January 14, Cardinal Trivulzio wrote in French to King François of France, speaking of his own vote for the election of the new pontiff. He also wrote to M. de Robertet on the same day (Molini, Documenti di storia italiana I, p. xxiii, xxiv).

The new Pope in Spain

Immediately after the election on January 9, a Congregation was held, and a special commission of Cardinals (Colonna, Orsini and Cesarini) was appointed to go to Spain and carry out all the necessary business to proclaim Adrian pope [Sanuto, 387-389]. Very detailed instructions were issued by the Sacred College (quoted in Gachard, pp. 10-19; Laemmer, Meletematum p.201 n.1) as to what should be done and how. On January 10, it was decided that, until the new pope should arrive, each month three cardinals (one from each of the Orders) should govern the Church: Carvajal, Scheiner and Cornaro—on February 10, they were to be replaced by Grimani, Fieschi and Cibo. Both Grimani and Cibo, however, begged off on grounds of ill-health, but their petition was refused. Fieschi refused to stay in the Apostolic Palace. The Bishop of Scala, Balthasar del Rio, was sent off to Spain with a letter from the Cardinals announcing the election of Cardinal Adrian.

The Emperor, who was in Bruxelles, heard the news on Saturday, January 18, 1522 [Brown, p. 207 no. 409; Sanuto Diaries 32, p. 308]. It was a chamberlain of Cardinal Carvajal, the Dean of the College of Cardinals who carried the letter of the Sacred College which informed Cardinal Dedel, who was at Vitoria in Spain, that he had been elected pope. The messenger arrived on February 9 (letter of Adrian to Charles, Gachard, p. 41). The new Pope had heard of his election, of course, long before the official messenger arrived. On February 2, he wrote to Cardinal Wolsey [Gachard, no. xiv, pp. 256-257] announcing his election and requesting the Cardinal's services in bringing about the treaty between Henry VIII and Charles V.

On the 11th the new pope wrote to the Emperor, seeking advice as to whether he should travel to Rome by land or by sea. Seeing that the commission of cardinals was being delayed in Rome, Adrian wrote out an acceptance in his own hand, had it notarized, and sent it to Rome with Giovanni Borel, his Protonotary Apostolic, he also advised the commission of cardinals not to come to Spain at all if they had not yet set out when his messenger arrived. When the cardinals received the declaration, they had it published to the people of Rome. Baldassare Castiglione reported to Isabella d'Este in a letter of March 26, 1522 (Serassi, 65) that the Cardinals had decided "che i Legati non vadino più fuor d'Italia, perchè questa andata potrebbe tardar molto Sua Santità". He provides the substance of the Pope's letter.

The pope departed Vitoria on March 12; on the 17th he departed Santo Domingo for Logrono. On the 25th he was in Alfaro. On the 28th he was in Pedrola. By March 29, the pope had reached Saragossa, where he spent several weeks (Pastor, Geschichte, 724-735, for letter of May 8), he wrote a letter to the College of Cardinals on May 19, explaining the reasons for his delay (Gachard, pp. 82-85), and again on June 3 about arrangements (Pastor, Geschichte, 725-726). Finally, in July, he arrived at Tarragona. On March 28, the Spanish ambassador in Rome, Don Juan Manuel, wrote to the Pope about the situation in the city (Gachard, 55-58); among other things he gives his observations on the attitudes of the various cardinals toward the pope. He says that there were some who wanted to void the election of Adrian and proceed to a new scrutiny, including Volterra, Colonna, Orsini, Ancona, Flisco, Como, Cavaillon, Monte, Aracoeli, Grassis, Grimani, and Cornaro; those most favorable to the pope included: Medici, la Valle, Sion, Campeggio, Cesarini, all the Florentines, Cesi, and Farnese.

Adrian's Arrival in Rome and Coronation