SEDE VACANTE 1314-1316

April 20, 1314 — August 7, 1316

New Cardinals

During his pontificate Clement V had appointed twenty-four cardinals, in three creations. His choices resulted in a notable scandal. Six of his choices were relatives (See Ehrle, Archiv für Literatur- und Kirchengeschichte 5 (1889) 149-158). Most of them were either fellow Gascons or cronies from one or another of his earlier episcopal appointments (Thomas Jors was Edward I's confessor). The Sacred College had no German or Spanish cardinals, and the Italian element (with no new appointments) came to be reduced to a mere eight. Cardinal Riccardus of Siena had been granted permission by Pope Clement on January 13, 1313, to leave the Curia and return to Italy for the sake of his health, for a period not to exceed two years [Baumgarten, Untersuchungen, p. 2; Regestum Clementis Papae V, VIII, 10014]. Cardinal Riccardus died at Genoa on February 10, 1314 [Regestum Clementis Papae V, VIII, 10268].

In a letter written by Cardinal Napoleone Orsini to King Philip IV in 1314, shortly after the death of Pope Clement V (April 20, 1314), the Cardinal bitterly complained that Clement had paid no attention to the Cardinals in making his appointments, in violation of the Electoral Capitulations of 1304 (Baluzius, II, 289-293; Souchon, 29-35):

Nam quasi nulla remansit cathedralis Ecclesia vel alicujus ponderis praebendula quae non sit potius perditioni quam provisioni exposita. Nam omnes quasi per emptionem et venditionem vel carnem et sanguinem possidentibus immo usurpantibus advenerunt. Dimittimus quod de XXIV Cardinalibus quos in Ecclesia posuit nullus in Ecclesia est repertus quae cum aliquando credita fuit sufficiens habere personas, sed per eum fuit hoc. Quinimmo nos Italici, qui ipsum bonum credentes posuimus, sicut vasa testea rejecti fuimus, adeo quod ad omnia quae ad statum cardinalatus respiciunt, sicut clerici praecipico periculosis negotiis mundi, cum quibus voluit Ecclesiis benedicis quibus placuit. Saepe etiam cassatis concordiis electionis, absque juris ordine, de valentibus personis, quando publicare volebat, in nostrum crepicordium vocabamur....

Imperial Coronation in Rome

Pope Clement V (Bertrand de Got) was happily settled in Avignon, though he was drawn home to Bordeaux from time to time. He governed the city of Rome through a Vicar (Annuaire pontifical 1903, p. 530). Pope Clement had originally agreed to crown the successful candidate for the Imperial Throne personally in Rome. But he found reasons to withdraw from his commitment to crown Henry of Luxembourg—who had not been the candidate of Philip IV of France, Clement's patron—and appointed a committee of five cardinals to carry out the act.

On November 1, 1311, Henry of Luxembourg received a delegation from Rome, which included the Orsini, Colonna, and Annibaldi, inviting him to come to the city to be crowned Emperor. Both they and Henry also sent embassies to Avignon to ask the Pope to come to Rome and carry out the coronation. (Baddeley, p. 82; Nicholas, Bishop of Botrinto, who was a participant in the events, relates the story in his Iter Italicum). In the Winter of 1312, Henry VII decided to set out for Rome to be crowned Emperor. In February he left Genoa, and spent some weeks in Pisa, due to bad weather. On April 23, he set out again for Rome, accompanied by Cardinals Niccolò Alberti (Ostia), Arnaud de Falguières (Sabina) and Luca Fieschi, (SS. Cosma e Damiano). Originally five cardinals had been appointed by Pope Clement to carry out the coronation (Acta Henrici VII, 42), but Cardinal Leonardo Patrasso (Bishop of Albano) had died.on December 7, 1311; and Francesco Orsini (S. Lucia in Silice) was also dead (Emperor Henry VII so states in his letter to the King of Cyprus on his coronation day [MGH, p. 803], and the surviving Cardinals remark in their Testimonium to the coronation [MGH, p. 797]: "nos praefati domini, nostri summi pontificis volentes oboedire mandatis, ad Urbem accessimus, bene memorie Albanensi episcopo et Domino Francisco prefatis viam universe carnis ingressis, invenimus ecclesiam Beati Petri apostoli taliter occupatam...." The words could be taken to imply that Orsini was dead before they reached the city of Rome on May 6.). The journey to Rome was filled with strife, since Henry was vigorously opposed both by the Guelfs of central Italy and by King Robert of Naples, who feared a revived Imperial empire in Italy, which was now, with the pope absent in France, under his domination.

Henry, in fact, was prepared to fight his way into the city of Rome against Guelf opposition, but his way was eased with the help of the Colonna. On May 6, he crossed the Milvian Bridge (Ponte Molle) and made his way to the Lateran Basilica, where he took up residence. Then the real troubles began on May 21 with fighting around Santa Maria in Aracoeli and the Capitol (Nicholas of Botrinto, in Baluze, 1196-1199; Gregorovius, VI. 1, p. 59-60):

Statim post Domini Regis ingressum in urbem inceperunt bella, destructiones domorum et multa alia mala. Gens Regis continuato insultu per duos vel tres dies turrim illam juxta pontem ceperunt et omnes qui erant ibi, et credo quod se reddiderunt salva vita. Post paucos dies illi qui tenebant Capitolium de nocte ipsum dimiserunt et gens Domini Johannis ad quem illi iverant intravit, habita pecunia ab eo ut publice dicebatur. Statim domum fratrum Minorum prope Capitolium [S. Maria in Aracoeli] muniverunt de aliquibus eorum, ne per illum locum gravarentur. Gens Regis post haec domum fratrum Minorum violenter intravit et, ut audivi, per consensum aliquorum fratrum, qui aliter non potuissent sine damno. Quosdam de illis qui locum muniverant ceperunt, et alii in Capitolium fugerunt ad suos socios. Postea videntes quod populus Romanus cum senatore parabant se ad dandum insultum contra Capitolium, quia multos de populo jam vulneraverant de balistis trahentes per fenestras ad diversa loca, dimiserunt Capitolium sic quod quilibet posset portare arma sua et una vice quicquid posset cum armis portare. Factum est sic. Dominus Ludovicus senator Dominum Nicolaum de Senis dimisit ibidem loco sui, quem etiam populus finito termino senatoris habere voluit, prout ad praesens recordor.

On May 25 King Henry ratified the appointment of Louis of Savoy as Senator of Rome, and Nicholas de Senis was appointed Louis' vicar. But the struggles continued. On the 26th the imperial forces sacked the Orsini palaces and burned them, as they were attempting to force their way through the Campo Marzio toward the Vatican, which was being held by the Guelfs against them.

From the moment of Henry's first entry into Rome it had seemed unlikely that he could be crowned in the traditional place, the Vatican Basilica. The three surviving Cardinals charged by the Pope with his coronation are named in a document in which Henry VII asks to be crowned at the Lateran Basilica instead, since he was unable to reach St. Peter's Basilica. The Vatican was in the hands of the Orsini and other Guelfs (May 10, 1312: Acta Henrici VII, Vol. 2, no. 18, p. 35-36):

... Serenissimus Princeps D(omi)n(u)s Henricus dei gratia Romanorum Rex semper Augustus dixit requisivit et protestatus fuit Reverendis in Christo patribus, d(omi)nis Arnaldo Sedis Apostolice legato Sabinensi et fratri Nycholao Ostiensi Episcopis, et Luce Sancte Marie in Via Lata dyacono cardinali ea que inferius continentu et primo inter cetera que idem dns. Rex dixit dictis dnis cardinalibus, narravit qualiter ipse venerat ad urbem coronandus dyademate imperii, et sacro carismate inungendus, et quod voluntas eius et desiderium erat ipsas coronationem et iunctionem suscipere in basilica principis Apostolorum dum cum ad ipsam basilicam comode pervenire posset. Verum tamen, quia per maliciam aliquorum malivolorum ipsius dni Regis tale impedimentum prestatur sic ut manifeste apparet quod etiam non potest aliqua tergiversatione celari, quod idem dns Rex ad eandem basilicam comode accedere non potest sine magno periculo personarum. Requisivit idem dns Rex et rogavit ipsos dnos cardinales ut ipsum impedimentum admoveant....

but even after the street warfare of May the Cardinals were unwilling to comply with King Henry's wishes. Their excuse was that they were waiting for further instructions from the Pope in Avignon. Nicholas of Botrinto and Ferreto of Vicenza ( II, p. 58 Cipolla) even say that when the people heard about the delay caused by the Cardinals they were so angry that they attacked the Cardinals and would have killed them, had not the King intervened and quieted the mob.

On June 22, the Emperor-elect finally ordered the cardinals to carry out the coronation at the Lateran Basilica, and the Cardinals reluctantly agreed to do so (Acta Henrici VII, no.21, pp. 48-50; Nicholas of Botrinto, in Baluzius, II, 1200). Henry was crowned at the Lateran Basilica (or what was left of it, after the ruinous fire of 1308) on June 29, 1312, the Feast of SS. Peter and Paul (Gregorovius, VI. 1, p. 59-60). The crown was placed on his head—under formal protest of the Cardinals, who did not have proper instructions from Pope Clement (The instructions which they did have are published in Acta Henrici VII Vol. 2, no. 20, pp.42-48). The coronation was carried out by Cardinal Niccolò Alberti, Bishop of Ostia (Ferreto of Vicenza II, 60-61; see Gregorovius, p. 60 n.3; and Baddeley, p. 106):

sicque a Rege in templum Beati Ioannis in Laterano denique ventum est, quo postquam studiosus applicuit, Nicolaus de Prato Hostiensis et Vellitrensis episcopus cardinalis, apostolice Sedis legatus, ad altare perveniens, missam in laudem apostolorum celebrem exorditur, cui ministrantes Arnaldus et Lucas memorati cum clero, solemnibus vocum iubilis pariter concinnunt. iamque post angelorum canticum et evangeliste sacri paginam simbolum decantarant, et ecce sacerdos memoratus ex ara bicipitem mitram nivei coloris accipiens, Caesare pronis genibus coram flexo, capite eius reverenter imposuit; dein protinus aureum diadema superponens, obsequio ministrorum adiutus, illi pomum aureum sinistra, sceptrum vero regium in dextra obtulit....

The Cardinal Bishop of Ostia already had permission from the Pope in his original instructions to anoint the Emperor, though the ceremonial in these instructions envisioned that the Pope himself would place the mitre and crown on the Emperor's head (Acta Henrici VII, p. 45).

Three days after the coronation, Henry VII was pressured to withdraw from the city. The city which he left behind was in chaos, many of its public buildings, palaces, homes and fortified areas in ruins. If Clement had been dismayed by Cardinal Napoleone Orsini's report of his legateship in Italy (March 1306-June 1309), then the news of these events surrounding the coronation of the Emperor Henry VII would have made him even more reluctant to return the Curia to what was left of Rome.

In 1314, Cardinal Napoleone Orsini wrote to King Philip IV (Baluzius, II, 289-290):

...Sed proh dolor, versa est in luctum cithara nostra. Nam Regi vel regno, si subtili merito pensentur defuncti [Papae Clementis] opera et sub eo gravia suborta pericula, nec provisum nec est praecautum sed praecipitia periculosa cautela subfossa, nisi divina manus per semetipsam misericorditer complanasset. Vrbs tota sub eo et per eum extremae ruinae subjacuit, et sedes beati Petri immo Domini nostri Iesu Christi disrupta est, et patrimonialis non per praedones potius quam rectores spoliata est et confusa, et adjuc subjacet vastitati. Italia tota, ac si non esset de corpore, sic quoad omnia est neglecta, immo dolosis anfractibus et comminatis seditionibus dissipata quod posset fides Christi in threnis Hieremiae renovare lamenta...

Death of Pope Clement V

Pope Clement V died at Roquemaure, near Avignon, on April 20, 1314. [On the date see: Finke, Papsttum und Untergang des Templerordens (Münster 1907) 99; Baumgarten, Römische Quartalschrift 22 (1908) 37 n. 1] He had made his Last Will and Testament on June 29, 1312 and had added a Codicil on April 9, 1314. The Will, which was extremely generous to his relatives, and which included a very large amount of money earmarked for a Crusade, was the subject of extensive litigation in the next reign (Ehrle, passim; Guérard, passim).Ptolemy of Lucca (Baluze, I, columns 55-56) says, on the authority of the Pope's confessor:

Eodem anno die XII Kal. Maii Clemens V moritur in quodam castro Regis Franciae quod dicitur Rochamaura. Fuerat autem multo tempore infirmus de tortionibus, ex quibus perdidit appetitum. Immo interdum patiebatur fluxum, et per ipsum mitigabantur tortiones. Interdum vero patiebatur vomitum. Et sic de talibus passionibus moritur; nec umquam fuit postea sanus postquam constitutionem contra religiosos mendicantes renovavit, sicut audivi a suo confessore fide digno.

It is said by John of Saint Victor that his body remained unburied for some time (Baluze, I, column 22):

Hoc etiam anno Papa Clemens feria tertia post quindenim Paschae obiit apud Carpentras. Gascones autem qui cum eo steterant intenti circa farcinas videbantur de sepultura corporis non curare, quia diu remansit insepultum.

Eventually, his body was transported across the Rhone to the town of Carpentras, where Clement had established his court. In August of the same year, according to Bernard Guidonis (Baluze, I, column 60), his body was removed to Gascony, where he was buried, according to his own wishes, in the Church of S. Maria de Usesta in Bazas.

Apparently, there were already papal ceremoniere by this time, who were keeping notes of papal events —though no names have been preserved. Franz Ehrle published a ceremonial concerning the Council of Vienne in 1311-1312, in Archiv für Litteratur- und Kirchengeschichte 4 (Freiburg im Breisgau 1888), 441-445.

The Electors

Eubel Hierarchia Catholica I second edition, p. 15 note 3. Cardinal Napoleone Orsini had complained to the Philip IV of the large number of Gascons, including six of his nephews whom Clement V had created cardinals—without consultation of the existing Cardinals, and in passing remarked that there were twenty-four living cardinals. King Edward II of England wrote individual letters to each of them on September 16, 1315 (Rymer, Foedera, III 534).

Clement V had created a total of twenty-four cardinals during his reign of eighteen years. Of these, there were three Dominicans: Nicolaus de Freauville (1305-1323), Guillaume Godin (1312-1336), and Thomas Jors (1305-1310); one Benedictine, Raymond de S. Severo (1312-1317); one Cistercian, Arnaud Novelli (1310-1317); and one Franciscan, Vitalis de Furno (1312-1327). Five of the six attended the Conclave of 1314.

- Niccolò Alberti, OP, Suburbicarian Bishop of Ostia e Velletri (from December 18, 1303). Previously Bishop of Spoleto (1299-1303); in 1302 he had been named Vicar of the City of Rome [Eubel I, p. 461 n. 1]. In February 1304 he was named Apostolic Legate in Tuscia and Lombardy; he returned to the Curia on July 14, 1304. (died April 1, 1321).

- Bérenger Frédol, of the Diocese of Maguelone in Languedoc, Suburbicarian Bishop of Tusculum (Frascati). Major Penitentiary [Rymer Foedera 3, 312 (April 1, 1312)]; for the first time, he remained in office during the Sede Vacante. He is called subprior Episcoporum by Cardinal Stefaneschi [Baluzius I, p. 684]. Doctor utriusque iuris [Gallia christiana 6, 341-344]. Professor at the University of Bologna. Canon of Beziers, Canon of Aix, Archdeacon of Narbonne, Bishop of Beziers (1294-1305) [Gallia christiana 6, p. 341-344]. He was one of the experts who worked for Boniface VIII on the Sextum [cf. Finke, Acta Aragonensia I, no. 96, p. 144]. He was created Cardinal Priest of SS. Nereus and Achilles on December 15, 1305, and subsequently dispatched to King Philip IV, along with Cardinal Stephen of S. Ciriaco, to conduct certain secret negotiations [Clement V to Philip IV (November 5, 1306): Baluze, Paparum Avinionensium Vitae II, p. 76; Philip's reply at p. 71, and cf. p. 90]. (died June 11, 1323).

- Arnaud de Falguières, of Miramont (Diocese of Bordeaux), a Gascon, Suburbicarian Bishop of Sabina. Archdeacon and Provost of Arles (by May 18, 1306, to 1307); sent by Clement V to Philip IV of France for secret negotiations [U. Chevalier, Gallia christiana novissima: Arles (1901) 1106-1107]. Archbishop of Arles (1307-1310), on the nomination Robert King of Sicily and Count of Provence [Gallia christiana 1 (1716), 574-575; U. Chevalier, Gallia christiana novissima: Arles (1901) 583-590]. He was one of the cardinals authorized to crown Emperor Henry VII in Rome in May, 1312; he left Avignon on June 19, 1311 and returned on October 6, 1313 [U. Chevalier, Gallia christiana novissima: Arles (1901) 590]. Former Legate in Lombardy and Tuscia [Regestum Clementis V, 9646 (April 4, 1313); 10338 (January 13, 1314)]. (died September 12, 1317). Nephew of Clement V.

- Guillaume de Mandagot, of Lodève, a Canon Regular of Saint Augustine, Suburbicarian Bishop of Palestrina. Canon of Nîmes, then Archdeacon. Archdeacon of Uzès. Papal Notary in the Roman Curia. He was named Archbishop of Embrun (1295-1311) by papal provision, and consecrated by Boniface VIII on the Sunday after Easter, 1295. He was sent by Boniface in the suite of Charles II of Sicily to Catalonia, where he succeeded in making peace between Charles and King James of Aragon [Gallia christiana 3, 1082-1084]. In 1296 he was summoned back to Rome and placed on the committee which was preparing the Sextum. Archbishop of Aix en Provence (1311-1312) [Regestum Clementis V, 7001 (May 26, 1311)]. (died September, 1321). He was the chosen candidate of the Italian cardinals at the Conclave of 1314.

- Arnaud d'Aux, Gascon, of La Romieu or Larromieu, in the diocese of Cahors, cousin of Pope Clement V. Suburbicarian Bishop of Albano. Canon of Coutances. Canon of Comminges. Vicar General of Bordeaux. Bishop of Poitiers (1306-1312) [Gallia christiana 2 (1720), 1188-1190]. Papal Chamberlain [Rymer Foedera 3, 312 (April 1, 1312); acceptance of his resignation by Clement V (May 19, 1312) in Baluze, II, p. 283]. Nuncio in England, with Cardinal Arnaud Nouvel, OCist, of S. Prisca, to arrange a peace between King Edward II and the English nobility (1312)—after the murder of Piers Gaveston [Rymer, Foedera 3, 349 (September 28, 1312)]; the Cardinal and Bishop were appointed on May 14, 1312 [Bliss, Calendar of Entries in the Papal Registers relating to Great Britain and Ireland II (1895), pp. 104-107], and were still in England in March, 1313 [Bliss, Calendar of Entries in the Papal Registers relating to Great Britain and Ireland II (1895), p. 117], and November 21, 1313 [Rymer Foedera III, pp. 450-451]. On December 22, 1313, Arnaud d'Aux was one of three cardinals appointed to absolve or impose the appropriate penalties on the Master, Visitor and Preceptors of the Knights Templars [Regestum Clementis V, 10337] S.R.E. Camerarius from May 19, 1312 to July 23, 1319. He was granted a pension by King Edward II of England, because of past and future services [Rymer Foedera III (London 1706), p. 468 (January 27, 1314)]. (died August 14, 1320, according to Eubel [probably a typo]; or August 24, according to Baluze, 670). His Testament is printed by Baluze, Vitae Paparum Avenionensium II, LVIII, pp. 388.

- Jacques Duèse, of Cahors [aged 70], a Gascon, son of Arnaud Duèse, sieur of Saint-Félix en Quercy. He had a brother, Pierre (who purchased the vicomté of Caraman) and two sisters. Marie married Pierre de Via (parents of Cardinals Jacques and Arnaud de Via), and Marguerite married Jean de Cahors (parents of Cardinal Gaucelin de Jean). Jacques Duèse was Suburbicarian Bishop of Porto e Santa Rufina (appointed after March 30, 1313, but before May 22, 1313) [Regestum Clementis V, no. 9112], previously Cardinal Priest of S. Vitale (created Cardinal in December, 1312). Doctor in utroque iure (Orléans). Formerly Chancellor of King Robert of Sicily [Almeric Augerio, in Muratori, Rerum Italicarum Scriptores III. 2, 470], from May, 1308 [V. Verlaque, Jean XXII, 31; but cf. p. 37, where the year 1307 is given]. Previously Bishop of Fréjus (1300-1310) on the recommendation of King Charles II of Sicily; and Bishop of Avignon (from August 29, 1310-1312) [Regestum Clementis V, no. 9041 (February 19, 1313)]. (died as Pope John XXII, December 4, 1334).

- Nicolas de Fréauville, OP, of Neufchâtel (Rouanne), a Norman [born at Rouen], Cardinal Priest of S. Eusebio, appointed on the recommendation of the King of France. Confessor of the King of France [according to Bernard Guidonis], and member of the Royal Council, on the recommendation of Philip IV's principal minister, Enguerrand de Marigny, Comte de Longueville [A. Touron, Histoire des hommes illustres de l' Ordre de St. Dominique II (Paris 1745), 36-37]. Taught theology at the University of Paris. Legate in France. He was one of the cardinals appointed by Pope Clement V in 1310 to examine the case of Boniface VIII, and to attempt a rapprochement between the Papacy and the French Crown. In 1312, he was assigned by Pope Clement the task of bringing peace between Philip IV and the Count of Flanders [Baluze, II, 149]. He then began to preach the Crusade in France. On the Wednesday after Pentecost, 1313, he enrolled as Crusaders King Philip IV, Edward II of England, Louis son of King Philip of Navarre, Charles Comte de Valois, and Louis Comte d' Evreux [Continuatio Chronici G. de Nangis sub anno 1313, Tome I, p. 396 ed. Geraud; Vidal, Benoît XII. Lettres communes I (Paris 1903) no. 2500]. In 1313 Cardinal Nicholas was appointed to raise the subsidy for the Crusade in France [Continuatio Chronici Guillelmi de Nangis, sub anno 1313; ed. H. Geraud, I, 396]. He was also assigned by Clement V to deal with the Knights Templars. His last Will and Testament of 1321 is provided by Baluzius [II, no. lxiv, pp. 409-425]; his executors were Cardinals Petrus de Arreblayo of S. Susanna (former royal Chancellor) and Napoleone Orsini of S. Adriano. (died February 14, 1323).

- Arnaud Nouvel, OCist, a Gascon, Cardinal Priest of S. Prisca (1310-1317) and (from 1311) Administrator of San Lorenzo in Damaso. Abbot of the Cistercian Monastery of Font-Froide (diocese of Narbonne). Legate in England, with Arnaud d' Aux, Cardinal Bishop of Albano, to arrange a peace between King Edward II and the English nobility (1312); they were appointed on May 14, 1312 [Bliss, Calendar of Entries in the Papal Registers relating to Great Britain and Ireland II (1895), pp. 104-108]. One of the problems they faced was the refusal of the English nobility to obey papal instructions in the sequestration of the property of the former Order of Knights Templars. Vice-Chancellor S.R.E. Legate in England (1312) [Bliss, Calendar of Papal Registers 2, p. 104 ff. (May 14, 1312)]. (died August 14, 1317)

- Bérenguer Frédol [Chateau de Veruna, near Montpellier], Cardinal Priest of SS. Nereo ed Achilleo (1312-1317), which had formerly been his uncle's titulus, and then Bishop of Porto (1317-1323). Nephew of Cardinal Bérenger Frédol. Doctor of canon law. He had been Vicar of Celestine V, one of the six clerics of the Camera, and participated in his funeral. Formerly Canon of S. Nazaire, Bishop of Beziers (1309-1313) [Gallia christiana 6, p. 345-346; Regestrum Clementis V, no. 9064 (March 5, 1313)]. (died November, 1323).

- Michel du Bec (Beton), Norman, Cardinal Priest of S. Stefano al Monte Celio. (died August 30, 1318)

- Guillaume Teste, of Condom, a Gascon, Cardinal Priest of S. Ciriaco alle Terme. Sent to England to collect the Peter's pence; he was still in England in 1313 [Rymer Foedera III (London 1706), 414 (May 20, 1313)].. Archdeacon of Ely. Archdeacon of Arran. Precentor of Lincoln. [Bliss, Calendar of Entries in the Papal Registers relating to Great Britain and Ireland II (1895), p. 116, 117, 118 (September 26, 1313); Regestum Clementis V, no. 9210]. He had lent King Edward II some 2000 marks Sterling [Rymer Foedera III (London 1706), p. 480 (May 26, 1314)]. (died 1326)

- Guillaume Pierre Godin, OP, of Bajona (Bayonne in Aquitaine), Cardinal Priest of S. Cecilia. (Died June 4, 1336) He had been a 'contubernalis' of Ptolemy of Lucca, and received the dedication of his Historia Ecclesiastica [Baluze, I, 672-673]

- Vital du Four (Vitalis de Furno), OFM, of Bazas in Aquitaine, Cardinal Priest of Ss. Silvestro e Martino ai Monti. (died August 16, 1327). Johannes Lupi says: Reverendus pater frater Vitalis tituli sancti Martini in montibus presbiter cardinalis, qui Vasco est et origine Vasatensis [Finke, Acta Aragonensium no. 240 p. 355].

- Raymond of S. Severo, OSB, from Bearne in Gascony, Cardinal Priest of S. Pudenziana. (died July 19, 1317).

- Giacomo Colonna, a Roman, son of Giordano Colonna, Signore di Colonna, Monteporzio, Zagarolo, Gallicano e Palestrina; and Francesca, daughter of Paolo Conti. Brother of Giovanni Colonna, Senatore di Roma, 1279-1280. Uncle of Cardinal Pietro Colonna and Stefano Colonna. Archdeacon of Pisa. Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Via Lata (March 12, 1278; deposed May 10, 1297; restored February 2, 1306), with S. Marcello in commendam. Archpriest of the Liberian Basilica [Langlois, Registres de Nicolas IV, I, no. 632, p. 128 (August 11, 1288)]. He died August 14, 1318, in Avignon). His nephew, Johannes de Polo, OP, had been Archbishop of Pisa (1299-1312) and then of Nicosia in Cyprus (1312-1332) [Regestum Clementis Papae V, no. 10345 (February 8, 1314)].

- Napoleone Orsini, son of Rinaldo Orsini and Cardinal Deacon of S. Adriano (1288-1342). Papal Chaplain (attested on February 18, 1286 [Bliss, Calendar of Papal Registers I, 483]. Canon and Prebend of Suthcave in the Church of York (before September 21, 1304-1342) [Le Neve, Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae III, 211; Bliss, Calendar of Papal Registers III, 199 (June 5, 1345)]. Shortly after the Conclave of 1304, the new pope made him Archpriest of S. Peter's [Regestum Clementis V I, no. 4 (September 19, 1305)]. Custodian of the Hospital of S. Spirito in Sasso, for life [Regestum Clementis Papae V, I, no. 3 (September 19, 1305)]. Nephew of Pope Nicholas III. [Cardella II, 33-37; Huyskens, passim]. (died 1342)

- Pietro Colonna, Cardinal Deacon of S. Angelo in Pescheria (1306-1326), previously of S. Adriano (1288-1297), with SS. Sergio e Bacco in commendam (1288-1290). Rector of the Romandiola [Regestum Clementis Papae V, I, 391 (March 22, 1306)] Archpriest of the Liberian Basilica (1318-1326) [Eubel I, p. 11 n.8]. He died at Avignon in 1326, and his body was transferred to Rome and buried in the Liberian Basilica in the Colonna family tomb [V. Forcella Inscrizione delle chiese di Roma 11, p. 16, no. 19].

- Guglielmo de Longhi, Cardinal Deacon of S. Nicola in Carcere Tulliano. (died April 9, 1319)

- Giacomo Caetani Stefaneschi, Cardinal Deacon of S. Giorgio in Velabro. (died June 23, 1341). Grandnephew of Pope Nicholas III [Cardella II, 51-53]

- Francesco Caetani, son of Goffredo of Anagni, brother of Boniface VIII. Canon of Porto. Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Cosmedin (1295-1317). Canon of Notre Dame de Paris [A. Molinier & A. Lognon, Obituaires de la province de Sens Tome I (Diocese de Sens) (Paris 1902)227]. Treasurer of York (1303-1306) [Rymer, Foedera III, 578; Le Neve, Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae III, 159]. Archdeacon of Richmond, Diocese of London (1307-1317) [Bliss, Calendar of Entries in the Papal Registers relating to Great Britain and Ireland II (1895), p. 53 (June 17, 1309; p. 93 (February 19, 1311); Le Neve, Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae III, 187]. He died on May 16, 1317 in Avignon.

- Luca Fieschi, Cardinal Deacon of SS. Cosma e Damiano. (died January 31, 1336)

- Arnaud de Pellegrue, Gascon [born at Bordeaux], Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Portico. (attested at the Conclave). Nephew of Pope Clement V. Archdeacon of Chartres (attested in 1305). He had been chamberlain of Clement V, before being created cardinal on December 15, 1305 [Regestum Clementis Papae V, I, no. 84 (November 27, 1305)], and Archdeacon of Chartres. (died August 1331: Eubel, 14, n. 6). He had been sent as Legate to make war against the Venetians, who had disobeyed papal orders about the succession to the Marquisate of Ferrara and who had thereby suffered the Interdict. He left the papal Court on January 25, 1309 [Eubel I, p. 14, n. 6]. He reconquered Ferrara on August 28, 1309, and turned the government over to King Robert of Sicily. He lifted the Interdict levied against the Florentines by Cardinal Napoleone Orsini during his Legateship; coincidentally he received at the same time 2000 gold florins as a gift from the Florentines in recognition of his success at Ferrara. He returned to the Curia in Avignon on December 10, 1310. He was sent by Pope Clement as one of the cardinals who were to crown Emperor Henry VII in Rome in May of 1312. He was also the recipient of a pension from King Edward II of England [Rymer Foedera III (London 1706), p. 413 (May 20, 1313); p. 453 (November 28, 1313)], in consideration of his handling English business at the Curia. He is a signatory of the letter of the Cardinals to the Commune of Perugia during the Conclave (Déprez, p. 114).

- Raymond Guillaume des Fargues, of Bordeaux, a Gascon, Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria Nuova, nephew of Pope Clement V. Archdeacon of Sens. Prebend of Ketton in the diocese of Lincoln 1308-ca. 1312) [Le Neve, Fasti II, 157]. Archdeacon of Leicester, from October 31, 1310 [Le Neve, Fasti II, 60]. Dean of Salisbury, from 1310 until his death [Le Neve, Fasti II, 614-615; Rymer, Foedera 3, 307 (February 18, 1312); Bliss, Calendar of Entries in the Papal Registers relating to Great Britain and Ireland II (1895), p. 107]. He is a signatory of the letter of the Cardinals to the Commune of Perugia during the Conclave (Déprez, p. 114). He died on October 5, 1346. Of Raymond and others of the relatives and followers of Clement V, Abbe Jean Roy, author of Nouvelle histoire des cardinaux françois, remarks: "Mais la plupart des créatures de Clement, foibles et contentes de la haute faveur dont ils jouissoient, s'endormirent sur le duvet de la fortune et des honneurs, en se laissant aller au gré des circonstances."

- Bernard de Garves, de St. Livrade, of the Diocese of Agen, a Gascon, a relative of Clement V (cousin or nephew?). Cardinal Deacon of S. Eusebio. In 1316 the new Pope made him Cardinal Priest of S. Clemente. Archdeacon of Coutances. He died in Avignon in 1328.

Salvador Miranda lists Aegidius Colonna (allegedly created in 1302) as not being in attendance. Curiously, although he notes the absence in 1314, he takes no note of Aegidio Colonna in the Conclaves of 1303 or of 1304-1305, though if Colonna had been made a cardinal in 1302, some comment would have been appropriate. One must agree that Colonna did not attend any of these conclaves. He was not a cardinal [cf. Cardella, II, pp. 65-67, who states, on the authority of Angelo Rocca, that Boniface VIII named him but did not publish his name. There is no documentary proof]. Aegidius Colonna was the son of Pietro Colonna, Castellan of Petrella; who was the son of Pietro Colonna the Lord of Genazzano; who was the son of Gregory Colonna, a soldier; who was the son of Pietro Colonna, a soldier; who was the son of Oddone Colonna, Signore di Colonna, Monteporzio, Zagarolo, Gallicano and Palestrina (though this lineage is somewhat disputed). Aegidio was a member of the Hermits of St. Augustine. He was a student of Thomas Aquinas, obtained a Doctorate in Theology, and was a Lecturer in Theology at Paris. He eventually became the Definitor of his Order, from 1284, and finally from 1292 the General of the OESA. He was made Archbishop of Bourges in 1295 (1295-1316), in succession to Simon de Bello Loco (Beaulieu) when Simon became a cardinal [Gallia christiana 2, 76-78; Eubel I, 138]. He was present at the Ecumenical Council of Vienne in 1311 [cf. Ehrle, Archiv für Litteratur- und Kirchengeschichte 4, 415-417]. He died in 1316 and was buried in the Church of the Augustinians in Paris. His epitaph does not mention a cardinalate [Oldoinus, Athenaeum romanum, p. 31]. Conrad Eubel says (I, p. 13, n.9): neque Aegidius Romanus neque Dominicus a.S. Petro ad dign. card. promoti sunt.

The Camerarius S. R. E. was Cardinal Arnaud d' Aux. He was appointed by December 2, 1311 [Leo König, Die päpstliche Kammer unter Clemens V und Johann XXII (Wien 1894), 77]. In accordance with a decree issued by Clement V at the Council of Vienne (October 1311—May 1312), the Camerlengo remained in office even during the Sede Vacante. The same decree applied to the Major Poenitentiarius. The Camerarius Sacri Collegii Cardinalium was Cardinal Bérenguer Frédol, Cardinal Priest of SS. Nereo ed Achilleo, created in April, 1313. He served until 1323 [P. Baumgarten, Untersuchungen und Urkunden über die Camera Collegii Cardinalium (Leipzig 1898), lii]

Conclave begins, and is ended

According to Prior Amalric (Baluzius, I, 111-112), twenty-three cardinals opened the Conclave in the Episcopal Palace at Carpentras after the obsequies for Pope Clement had been completed. According to the regulations of Gregory X, this would have been on May 1, 1314 (Souchon, 36). The cardinals conducted their business pacifice et quiete, though without a successful election, until the Feast of S. Mary Magdalen on Monday, July 22, 1314. The Pope who was finally elected makes mention of the situation in his electoral manifesto, Mira et inscrutabilis [Luca D' Achery, Veterum aliquot scriptorum spicilegium XI (Paris 1672), p. 388 (Lyon, September 5, 1316)]:

... Dudum siquidem, sicut tuam credimus notitiam non latere, sanctae recordationis Clemente Papa V. praedecessore nostro de praesentis vitae moeroribus ad caelestem patriam evocato, nos et fratres nostri ejusdem Ecclesiae Cardinales, de quorum numereo tunc eramus, cupientes eidem Ecclesiae de pastore celeriter providere juxta constitutionem Apostolicam super hoc editam, nos inclusimus in Conclavi quod in civitate Carpentoratensi, ubi tunc Romana curai residebat, ad hoc extiterat praeperatum. Demum vero electionis praedictae negotio imperfecto, ex certis causis legitimis, Conclave praedictum egredi necessitate compulsi, nos ad diversa loca transtulimus, prout unicuique nostrum expediens visum fuit....

It is known that the Italian party had their own candidate from the beginning of the Conclave, Guillaume de Mandagot, Bishop of Palestrina. This is stated by Cardinal Napoleone Orsini himself, in a letter which he wrote to King Philip IV of France in 1314 (between April 20, when Clement V died, and November 29, when Philip died) [Baluzius, II, 289-293]:

Licet aliqui inter nos Italicos sint boni, et bonos alios in diversis partibus cognoscamus, quia tamen non fuimus sicut fuimus, corde sic opere nos communes ad rem facibilem et communem nostros concurrimus cogitatus, et nominavimus a principio et in eo stamus firmi, Cardinalem bonae famae, rectae, ut credimus, conscientiae, excellentis scientiae, probatum in multiplici regimine, et in omnibus suis actibus a cler et populo commendatum, et qui est de regno et aleator honoris Regis et regni, corde sincero, non vacuo verbo, et per defunctum Pontificem ad archiepiscopatum Aquensem et postmodum ad cardinalatum assumptus est, et aliis Cardinalibus est amicitia multa conjunctus, ita quod quasi omnibus erat sicut unus ex eis. Nos in eo nihil habemus aut quaerimus nisi dreditam bonitatem. Hic Dominus Guillermus Dei gratia Episcopus Penestrinus, de quo nos populus et clerus dedimus quod statum Vascones acceptarent.

But the nomination of Guillaume de Mandagot, Bishop of Palestrina, a Frenchman and a subject of the King, was resisted by the Gascons, to everyone's stupefaction, and no explanation for the rejection was forthcoming.

Failed Conclave, 1314

Then, on July 22, 1314, something happened. Because of very serious discord which arose among the attendants of the cardinals, which nobody in the world was able to pacify (according to Amalric), the Cardinals left the Conclave. They agreed, however, that once they had their retinues under control, they would return to the Conclave. They were unable, however, to achieve that end. Worse, the violence increased and the discord enveloped the Cardinals themselves.

John, Canon of St. Victor's in Paris (Baluzius I, 113) provides more details, in particular as to a fire which was caused by the Gascons and which burned down the greatest part of the city of Carpentras:

Cardinales apud Carpentras ut de pastore providerent Ecclesiae convenerunt. Sed effusa est contentio super principes, nec poterant concordare. Italici talem eligere intendebant qui ad Romanam sedem curiam revocaret. Quod Cardinales Gascones facere formidabant: quia cum sui de Gasconia Italicis multas injurias irrogassent, certi erant quod si in manibus Romanorum inciderent, aequipollentiam sustinerent. Fuerunt ergo diu in tali discordia, licet inclusi multa incommoda sustinerent, quia cibaria eorum subtrahebantur, et domus eorum desuper dissipatae. Tandem haec Vascones non ferentes, ignem in palatio posuerunt, per quem combusta est pars maxima civitatis. Et sic dispersi Cardinales. Et licet secundum statutum in urbe qua moritur Papa debeat electio celebrari, tamen Italici omnino discordabant, volentes quod electio ad curiam Romanam transferretur, et alii alibi. Ideo sunt dispersi.

The Italian cardinals were demanding that the election be transferred to Rome. In the meantime they dispersed, a number of them taking up residence at Valence.

Unwilling to return to the Conclave out of fear of the Gascons, the Italian Cardinals scattered to various towns and castles and for two years remained dispersed. King Philip IV, who was still alive and who had heard of the recent breakup of the Conclave, wrote to Cardinals Bérenger Frédol (Bishop of Tusculum) and Arnaud de Pellegrue (Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Portico, and nephew of Clement V). He exhorted the Cardinals to select some place where they would all feel safe, whether inside his domains or outside of them, suggesting vigorously that that place should be Lyons. He admitted that the Italian cardinals had a valid reason for refusing to go to Carpentras or Avignon. To facilitate an agreement, he suggested that a committee be selected, one member from each side, Gascon and Italian, and as a third member Cardinal Nicolas de Fréauville, his own friend and confessor (Baluze, II, 293-297). His intervention produced no result. King Philip finally died on November 29, 1314.

On September 10, 1314, six of the Cardinals of the Italian faction, gathered at Valence, wrote an indignant public letter, addressed (in one surviving exemplar) to the General Chapter of the Cistercian order as well as to several individual monasteries (Baluzius II, 286-289), and in another copy addressed to King Edward II of England (Rymer, Foedera III, 494-495). The letter was signed by Niccolò Alberti (Ostia and Velletri), Napoleone Orsini (S. Adriano), Guglielmo de Longhi (S. Nicola in Carcere), Francesco Caetani (S. Maria in Cosmedin), Jacopo [Giacomo] Colonna (S. Maria in Via Lata) and Pietro Colonna (S. Angelo in Pescheria). They narrated their own version of the events of July 24, blaming the whole affair on the Gascons and labelling it an act of careful premeditation, led by two nephews of the late Pope Clement, Bertrand de Got and Raymond Guillermi:

...Et quidem dum nos et alii ejusdem Ecclesiae Cardinales post obitum Domini Clementis Papae quinti essemus in palatio civitatis Carpentoratensis ad eligendum futurum summum Pontificem sub uno conclavi, et nos Cardinales Italici ... subito Vascones, seu quod libram examinis sub futuro summo Pontifice teste conscientia formidarent, seu quod armorum violentia crederent hereditario jure Dei sanctuarium possidere, ex deliberato atque proposito, tamen sub palliato colore, deferendi videlicet corpus ejusdem Papae in copiosa peditum et equitum armatorum multitudine convenerunt, et scelus quod mente conceperant producentes in actum, die XXIV Iulii arma sumpserunt bellica, et sub ordinatione Bertrandi de Guto et Raymundi Guillermi Domini Papae nepotum civitatem Carpentoratensium intrantes, multes curiales Italicos, cum soli Italici peterentur ad mortem, inhumaniter trucidarunt, et se ad praedam convertentes et spolia, crescente rabie ac ad crudelia fervescente furore, in diversis civitatis partibus incendia posuerunt. Nec iis contenti, plurimorum Cardinalium ex nobis hospitia duris insultibus et injectis ignibus invadentes, bella ibidem acerrima cum clangore tubatum hostiliter intulerunt.

Invalescente tandem graviori periculo et gravissimo, sicut in captis civitatibus assolet, increbrescente rumore, multitudo Vasconum et equitum armatorum ostium dicti convlavis obsedit acclamando: Moriantur Cardinales Italici. [Volumus Papam, volumus Papam. et ipsis in hujusmodi acclamatione frementibus, alia multitudo Vasconum et equitum armatorum plateam dicti conclavis invasit, similibus circumdato palatio vocibus acclamando, Nos vero praefati Cardinales Italici] circums(a)epti tantis angustiis et mori tam turpiter tam crudeliter metuentes, cum omnia circa conclave armatorum multitudo teneret, neque publicus pateret egressus, tandem posteriorem murum palatii, facto inibi parvo foramine, pro nostro salute rupimus: de Carpentorate postmodum dispersi discedentes non sine mortis periculo ad diversa loca discessimus, et per misericordiam Dei ... ad terras pervenimus amicorum.

A similar letter of complaint and explanation was sent to King Jaime II of Aragon.

This encyclical letter was a particular embarassment to King Edward, who was the overlord of Bertrand de Got, and with whom he had been doing business in the name of Pope Clement and of Bertrand himself, and with whom he was still engaged —Edward was in need of funds for his Scottish War (Rymer Foedera III, 504 and cf. 545 and 571-572). King Edward did write a letter on December 4, addressed to Cardinal Niccolò Alberti, the Bishop of Ostia, urging the cardinals, in the most general terms and most conventional language, to get on with the business of electing a pope. Cardinal Alberti was well-known to King Edward, since he had been the Legate to England and France in 1301, charged with arranging a peace between the two.

King Jaime of Aragon responded to the same cardinals in a letter sent from Lerida on October 20, 1314 (Finke, Acta Aragonensia, 200-201). The King's remarks acknowledge the grave scandal presented to all of Christendom by the failure of the Cardinals to elect a pope, though he very diplomatically avoids taking sides or placing blame, or, for that matter, intervening.

On the Vigil of the Feast of St. Andrew, November 29, 1314, King Philip IV of France died. He was succeeded by Louis X.

No Conclave, 1315

Early in January of 1315, King Jaime wrote to his accredited representative to the Roman Curia, Bishop Guillaume de Villamarin of Gerona, advising him to approach the Cardinals in Avignon, and, using whatever diplomatic language seemed appropriate to the situation that he might find, convince the Cardinals to proceed to a quick election of a pope. Under no circumstances, however, was the BIshop to respond in any way favorable to a suggestion that the presence of King Jaime at the Conclave might be helpful to resolving any difficulties. The Ambassador-Bishop carried out his mission.

On February 10, 1315, Cardinal Jacopo Colonna, the senior Italian Cardinal, who was staying in Valence, wrote to King Jaime of Spain, protesting that the Cardinals, including himself, were doing everything they could to elect a pope, hoping that the Church could be saved and praying that God would grant it, qui dudum se cum ea electa et sponsa sua clementer a morte roseo sanguineo redempta in finem usque promisit seculi permansurum. (Finke, Acta Aragonensia, 204).

A reply on behalf of the French and Gascon Cardinals who were gathered at Avignon was sent to King Jaime on February 24, 1315, by Cardinal Arnaud de Pellegrue (Arnaldus de Via), a Gascon, the Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Portico. He protests that the cardinals at Avignon had offered ten names to the Italian Cardinals, from among whom they could select the one they wanted as pope. They subsequently offered the Italians any place in all of France or Provence they might choose as a meeting place for the resumption of the Conclave. Both offers were still on the table. The Italian Cardinals made only one counter-offer, a place to hold the Conclave, but it would have to be in the Empire and in Italy (...nominantes nobis loca imperii et loca etiam ultramontanes pro electione hujusmodi celebranda). In other words, the Italian cardinals wanted to be out from under the domination of the French king. Cardinal Guillaume Pierre Godin, OP, (S. Cecilia) wrote a similar letter at the same time (Finke, Acta Aragonensia, 205-206)

King Louis X of France was not entirely neutral in the matter of the election of a pope either. He wished to secure a loan as well as soldiers from Clement V's nephew, Bertrand de Got, for his Flemish War. This would require a favorable attitude on the part of the King to Gascon interests, and that might affect the voting in the Conclave, where the Gascon cardinals held a prominent position. The royal agent in these negotiations, Pierre de Barrières, Bishop-Elect of Senlis, was also instructed to bring the cardinals together again to resume the Conclave. Documents indicate that Bishop Pierre left Paris accompanied by the Comte de Boulogne on February 3, 1315, and arrived in Avignon on February 17. He was ordered by King Louis to contact Bertrand de Got, and that they should work jointly to persuade the Cardinals to assemble at Lyon. The Bishop-Elect was successful in negotiating with Bertrand de Got. Completely unsuccessful in spurring the Cardinals to action, however, he left Avignon for Paris on April 14 [Bertrandy, 56]. In the same year King Louis' marital difficulties became critical. He had undertaken to marry Clémènce of Hungary, even though his current wife was still alive and kept in confinement for life in the Chateau-Gaillard, having been arrested, tried, and found guilty of infidelity by the Parlement. Nonethess, she and Louis were still legally married, and the dissolution of that marriage would require the active cooperation of a pope. Time was of the essence, since Clemence was already on her way to France from Naples [Bertrandy, 10-11]. Hugh de Beauville, the Royal Chamberlain had left on December 12, 1314, and returned on August 12, 1315 [Bertrandy, 57]. But no pope was forthcoming during those eight months, and therefore no annulment was possible. Queen Margaret presently died, on August 14, 1315, under suspicious circumstances, and five days later Louis and Clemènce were married.

On September 16, 1315, King Edward II of England wrote to each of the twenty-four cardinals [Rymer, Foedera III, 534], having received a detailed briefing from his recently returned procurators, Gilbert Becche and Antonius Pessaigne de Janua; he urged them once again to end the scandal of the vacancy and proceed quickly to the election of a pope. Yet another letter, sent from York on October 5 [Rymer, Foedera III, 538] was tinged with some asperity:

Cur non attenditis quae, exactis temporibus, ipsius ecclesiae prolixa vacatio, quae praedecessorum vestrorum dissentio nota dispendia intulerunt? Cur non praeteritorum confideratio vos edocet mala declinare praesentia, et futura pericula praecavere?

There is a letter from the Cardinals in the Municipal Archives of Perugia which may indicate the split in detail. The Magistrates and Commune of Perugia had written to the Cardinals to deplore the failure to elect a new pope and to urge them to carry out an election. The Cardinals' reply is dated April 10, but unfortunately without a year—which could be 1315 or 1316. The document is signed by fourteen out of the twenty-four cardinals [Déprez, p. 114]:

Arnaldus Sabinensis

Guillelmus Penestrinus

Jacobus Portuensis, episopi

Fratres Nicolaus Sancti Eusebii et

Arnaldus Sanctae Priscae

Berengarius Sanctorum Nerei et Achillei

Raymundus Sanctae Potentianae

Michael Sancti Stephani in Caelimonte

Fratres Guillelmus Sanctae Ceciliae et

Vitalis Sancti Martini in Montibus et

Guillelmus Sancti Ciriaci in Termis, titulorum presbiteri

Arnaldus Sanctae Mariae in Porticu

Raymundus Sanctae Mariae Nuovae et Bernardus Sanctae Agathae, diaconi cardinalis

Not signing are nine cardinals: Niccolò Alberti, OP, Bishop of Ostia e Velletri; Arnaud d'Aux, Bishop of Albano; Giacomo Colonna, Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Via Lata; Napoleone Orsini, Cardinal Deacon of S. Adriano; Pietro Colonna, Cardinal Deacon of S. Angelo in Pescheria; Guglielmo de Longhi, Cardinal Deacon of S. Nicola in Carcere Tulliano; Giacomo Caetani Stefaneschi, Cardinal Deacon of S. Giorgio in Velabro; Francesco Caetani, Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Cosmedin; and Luca Fieschi, Cardinal Deacon of SS. Cosma e Damiano. With the exception of Arnaud d' Aux, the absent cardinals constitute the Italian Faction. Their absence presented a difficult problem. Could the Conclave proceed in their absence? The fourteen did not constitute a two-thirds canonical majority, even if they were unanimous in a choice. If they did attempt to proceed, would a schism be provoked? (cf. Finke, Acta Aragonensia, 208 and again 209) Could Cardinals be deprived of their right to vote? Surely not. In earlier elections, when a cardinal was not present (as in 1271), special efforts were made to procure an explicit renunciation of their rights, and even then, after the election (as in 1271 and 1305) the cardinals made every effort to have the absent cardinals sign the Electoral Decree. Clement V himself had enacted provisions at the I Council of Vienne (1311-1312), in the Constitution Ne Romani electioni, [Clementines Lib.1, tit. 3, de electione, cap. ii]:

Ceterum, ut circa electionem praedictam eo magis vitentur dissensiones, et schismata, quo minor eligentibus aderit dissidendi facultas, decernimus, ut nullus Cardinalium cujuslibet excommunicationis, suspensionis, aut interdicti praetextu, a dicta valeat electione repelli: juribus aliis circa electionem eandem hactenus editis, plene in suo robore duraturis.

W. C. Cartwright [On the Constitution of Papal Conclaves (Edinburgh 1868), 133-134] remarks:

"It was felt that a Pope of headstrong passions like Boniface VIII. must absolutely be precluded from exposing the Church again to grave peril for the sake of purely personal hatreds and ambitions. Accordingly, just thirteen years after the memorable degratation of the Colonna Cardinals, A Bull in reference to Papal elections was issued by Clement V., in which the following most remarkable clause was inserted:—But in order that, as concerns the before-mentioned elections, dissensions and schisms be so much the more avoided, as the occasion for dissent is removed from theose elections, we decree that no Cardinal may be expelled from the said elections on the ground of any excommunication, suspension, or interdict whatsoever. The provision thus made has been subsequently confirmed by Pius IV. and Gregory XV. in so full a manner as to remove all ambiguity on this head.... There are instances of Cardinals who, since this enactment, have undergone extreme penalties, even decapitation; but we know of no instance in which this particular provision in regard to the indelible right of franchise has been set at nought."

1316: French Intervention

Finally, at the end of 1315, after two years without a pope and without a conclave, the king of France decided to intervene again. The Bishop of Senlis embarked on another embassy to the south, departing Paris on December 26, 1315. He spent seventy days going back and forth between Avignon and Valence (Bertrandy, 14). King Louis the Stubborn finally sent his most politically astute brother, Philip Count of Poitou, to persuade the Cardinals to begin their deliberations again. This decision must have been taken not long after Christmas of 1315, for Bernard Guidonis [Baluze, I, 131] remarks that Count Philip had worked for six months without successfully getting the conclave to resume:

... tandem congregati fuerunt pariter et inclusi diligentia, arte, et ingenio Domini Philippi tunc Comitis Pictaviae germani Regis Franciae Ludovici, cui successit in regno Franciae, qui ad hoc antea anno fere dimidio laboraverat multis modis, cum non potuisset in unum locum alias congregari. Et quadragesima die ab inclusione ipsorum, quae facta fuit in Vigilia Apostolorum Petri et Pauli, ipsis tamen quod tunc deberent includi nescientibus pariter et invitis, tandem tractatu praehabito in praefatum Dominum Johannem omnes pariter consenserunt.

It may even be that Count Philip was the force behind the embassy of Pierre de Barrières, Bishop of Senlis. Count Philip took up his residence in Lyons and began trying to pursuade the Cardinals to assemble there under his protection. Movement on the part of the cardinals can be detected in mid-March.

Some details of the movements of the cardinals are provided by the Spanish archives. Joannes Lupi wrote to King Jaime from Avignon on March 18, 1316, that the Norman Cardinal Nicolas de Fréauville, OP, (S. Eusebio) was already almost at Lyons. Cardinal Guillaume de Mandagot (Palestrina) was starting out that very day. Cardinals Bérenger Frédol (Tusculum) and his nephew Bérenguer Frédol (SS. Nereo ed Achilleo) were also departing Avignon that day. The rest of the cardinals would be heading for Lyons soon (Finke, Acta Aragonensia, 206). These, however, were members of the French contingent. There was as yet no sign of the Italians, though they do seem to be assembled at Lyons with the French by the beginning of June..

Unfortunately Louis X died on June 5, 1316, of the effects of a strenuous game of tennis. He was without male issue but with a pregnant wife. (The baby, who was named John, lived only five days, dying on November 20, 1316) John of St. Victor says that King Louis' death was the turning point for the efforts of Philip Count of Poitou, who had to make some immediate and important decisions as to the government of France. He could not stay in Lyons any longer, neither could he leave the Cardinals without getting them to produce a pope. He had previously sworn that he would not impede the cardinals from coming and going from Lyons (Finke, Acta Aragonensia, 208) , but now he obtained learned advice (de consilio theologorum) that such an oath was illicit. Immediately, therefore, he locked the Cardinals up in the convent of the Dominicans in Lyons [Baluze, I, 115; Muratori RIS, pp. 679-680]:

Comes autem Pictavensis audiens mortem fratris, admodum fuit stupefactus. Non enim utile videbatur ulterius trahere moram in Lugduno nec electionis Papae negotium dimittere imperfectum. Consilio igitur habito judicatum extitit per prudentes quod de non includendis Cardinalibus erat illicitum quod fecerat juramentum. Tunc eos omnes in domo Praedicatorum ad colloquium convocavit. Quibus dixit quod inde non recederent donec de Papa Ecclesiae providissent. Positis ergo custodibus qui eos exire non permitterent, ipse in Franciam est reversus.

Conclave and Election of Jacques Duèse (d'Euse)

Finally on June 28, 1316, the Cardinals unwillingly returned to the conclave and began their deliberations again (Bernard Guidonis, in Baluze, I, column 151):

Et quadragesima die ab inclusione ipsorum, quae facta fuit in Vigilia Apostolorum Petri et Pauli, ipsis tamen quod tunc deberent includi nescientibus pariter et invitis, tandem tractatu praehabito in praefatum Dominum Johannem omnes pariter consenserunt.

Johannes Lupi, the Procurator at the Roman Curia of the King of Aragon, was able to write to King Jaime on June 30 that the Cardinals had been assembled in the Convent of the Dominicans and were ordered by Count Philip of Poitou through his friend the Count of Forez to elect a pope [Finke, Acta Aragonensia, 207]:

Sane, serenissime princeps, vos scire cupio quod die lune vigilia apostolorum Petri et Pauli , que fuit IIII Kalendas Julii, domini cardinales tam Italici quam Citramontani omnes numero XXIII, ut consueverunt alii, ad domum Praedicatorum convenerunt. Ipsis vero in loco solito existentibus milti de familia comitis Pictavensis aparuerunt armati, plures quam diebus aliis retroactis. Et paulo post iuxta horam terciam comes ipse misit ad eos comitem de Foresio, qui ex parte sua notificavit eis, quod darent operam omnino ad eligendum papam. Nam scirent, quod numquam inde exirent, quousque summum pontificem elegissent. Et statim fuit ordinatum inter eos, quod remanerent duo domicelli et unus capellanus cum quolibet cardinalium et alii omnes recederent, et in continenti omnes alii recesserunt. Comes autem ipse Pictavensis, licet disposuisset recedere, deliberavit remanere quousque papam penitus habeamus, et ubi ipsum contingat recedere, comes de Foresio remanebit hic pro eo, qui est potentissimus in pratibus istis, ad custodiam cardinalium et civitatis, qui forcius et arccius constitucionem domini Gregorii X contra eos faciet observari.

There was a certain amount of complaint against the Count of Poitou, who, it was alleged, was excommunicated because he had broken his oath and locked the cardinals up in Conclave. But he paid no attention. Forez became the governor of the Conclave.

It was reported to King Jaime on Wednesday, July 21, by Arnaldo de Cumbis, his Procurator at the Roman Curia, that Cardinal Arnaud d'Aux, a Gascon (Bishop of Albano), would have been elected on the day that the Conclave resumed, had it not been for Count Philip, who caused four votes to be withheld by announcing that Cardinal Arnaud was not acceptable to the King of France (Finke, Acta Aragonensia, 210):

Dicitur tamen hic communiter et ita audivi ab hominibus fide dignis et qui dicunt se scire pro certo, quod Cardinalis Albus fuisset papa die qua fuerunt retenti, nisi Dominus Comes Pictavensis impedivissent, qui sibi abstulit IIII voces pro eo, quia non reputat eum amicum regis Francie, sed pocius creditur, quod fuit, tamen quia ipse vel domus Franciae nollent hominem ita iustum set qui eorum voluntatem in omnibus adimplerent. Alique eciam Gallici dixerunt quod dictus cardinalis nimis diligit vos et dominum regem Maioricarum et totam domum vestram.

Arnaldo also reports that Count Philip made it known to the Cardinals, through the Count of Forez, who the acceptable candidates were, as far as the French Crown were concerned:

Dominus Philippus nunc regens regnum Francie in recessu suo de loco isto dimisit comiti Foresii quandem cedulam, in qua continebatur, quod placebat sibi, quod eligeretur iu papam dominus Tusculanus [Bérenger Frédol], vel dominus Penestrinus [Guillaume de Mandagot], vel dominus A(rnaldus) dc Pelagrua vel dominus Berengarius tituli sanctorum Nerei et Achilei presbyter cardinalis, nepos domini Tusculani [Bérenguer Frédol] , vel dominus Portuensis [Jacques Duèse].

The same Arnaldo de Cumbis reported that, since the Cardinals had been enclosed on July 28, only one scrutiny had taken place. Neither did one take place between July 21 and his next letter on July 29. He did pass on some inside information as to the alignment of cardinals and their candidates:

Ytalici nominant dominum Penestrinum [Guillaume de Mandagot] et dominum Alb(an)um [Arnaud d'Aux], Citramontani sunt divisi: Uascones enim volunt dominum Arnaldum de Pelagrua pro quo eciam dominus comes rogavit instanter, Provinciales et alique Gallici vellent dominum Tusculanum [Bérenger Frédol]. Sunt multi insuper, quorum quilibet velle pro se ipso. Et nullomodo Citramontani volunt papam extra collegium, nam cum sint XVII et alii VII possent facere extra collegium, quemcumque vellent, set in hoc eciam non possent esse concordes.

Certainly the preference of the Italians had not changed since the beginning of the Conclave more than two years earlier. As Cardinal Napoleone Orsini had pointed out, the Bishop of Palestrina was their choice. The statement that Arnaud d'Aux was also their candidate may well explain why he was one of the cardinals, the only Frenchman, who did not sign the letter to the Perugians earlier in the Sede Vacante. Even under pressure from Count Philip, who held them prisoner in Lyons, it took the Cardinals forty days to achieve a successful election. This came on August 7, 1316 (Bernard Guidonis, in Baluze, I, 133: electus fuit in summum Pontificem in conventu fratrum Praedicatorum Lugduni VII. Idus Augusti, in sabbato). The news was reported immediately, on August 7, to the King of Aragon by his Procurator, Joannes Lupi [Finke, Acta Aragonensia, 212]:

Princeps serenissime. Noveritis, quod die sabbati VII. Idus Augusti dominus Jacobus episcopus Portuensis dudum Avinionensis, qui de Catursio trahit originem et iam pridem fuit cancellarius regis Roberti, electus fuit in summum pontificem. Et eius electio fuit publicata et ipse venit ad ecclesiam cum pluviali et mitra cruce precedente et recepit aliquos ad reverenciam. Et statim reintravit cameram et assumpsit sibi nomen Johannes. Utinam placabilem eum faciat nobis Deus! Et factus est propter discordiam Italicorum. Nam dominus Neapoleo discessit a domino Petro de Collumpna et ipse et dominus Franciscus et dominus Jacobus Gayetanus consenserunt in eum.

In a second letter on August 11, Johannes Lupi had more information to pass on. The change in the votes of the Cardinals had taken place in fact the day before the successful election, on August 6, because of a private meeting of the Italian Cardinals (Finke, Acta Aragonensia, 215-216):

Noveritis itaque, excellentisime d[omine], quod, [cum] varii tracatus habite fuisent inter cardinales, tandem die iovis nonas Augusti domini Italici per se fuerunt in magno colloquio. Et licet aliquale odium esset inter dominum Neapoleonem et dominum P[ietro] de Columpna, tamen usque ad illum diem semper Italici in facto electionis fuerant in concordi proposito, tunc vero, cum Dominus Petrus vellet ad suam voluntatem omnes trahere, patenter fuit rupta eorum concordia, ita quod dominus Neapoleo dixit ei: Faciatis facta vestra, ut melius poteritis, et nos faciemus n[ostra! Et] tunc dominus Neapoleo et dominus Jacobus [Gaye]tani et dominus Franciscus univerunt se cum domino Arnaldo de Pelagrua et sequacibus suis in favorem regis Roberti, ut haberent omnino istum Portuensem [Jacques Duèse].

Et ecce, quod sequenti die, cum ipse iam certus esset de XVIII vocibus cardinalium, cum scrutinium deberet fieri, subito videntes alii, quod complementum vocum haberet etiam sine eis, fecerunt de necessitate virtutem et absque alio scrutinio ipsum concorditer in summum pontificem elegerunt. Et statim assumpsit sibi nomen Johannes, et, ecce, eum papem!

Die lune V. idus Augusti vocati fuerunt ad consistorium cardinales et ordinavit in primis, quod audiencia causarum et litterarum resumeretur Avinione in kalendis Octubris.

The contemporary sources are unanimous that the election was accomplished by twenty-three cardinals (not, of course, including the new pope). In fact, as Johannes Lupi explains, on the morning of August 7 it was clear that Cardinal Duèse had eighteen solid votes, thanks to the faux pas of Pietro Colonna, and therefore, when the hold-outs suddenly realized the fact, they made a virtue out of necessity and without any scrutiny they acclaimed Cardinal Duèse unanimously. The successful candidate was none of the papabili, but rather Cardinal Jacques Duèse, a Gascon, the Bishop of Porto and Santa Rufina.

On August 11, 1316, Arnaldo de Cumbis, one of the Aragonese Procurators at the Roman Curia, wrote to King Jaime, "Dominus Napoleo dixit michi, quod dominus Papa intendit modis omnibus ire Romam, si posset fieri pax predicta." That appears to have been the understanding of the Continuator of Ptolemy of Lucca [Baluzius I, col. 178], who says that Orsini refused to attend at the making of the Last Will and Testament of Pope John on November 3, 1334, because he was still indignant against the Pope quia Papa in sua electione, quae apud Lugdunum celebrata fuit, juravit se numquam ascensurum equum vel mulum nisi iret Romam. Though this may well have been a personal undertaking by Pope John with Cardinal Napoleone, there is some possibility that there were Electoral Capitulations in 1316, and that Cardinal Napoleone Orsini's indignation derives from the breaking of one of those promises [See Souchon, p. 45].

Coronation of John XXII

Pope John XXII was crowned in the Cathedral of St. Jean in Lyons: fuitque coronatus more Pontificum Romanorum Lugduni in Ecclesia cathedrali Nonis Septembris, Dominica prima eiusdem mensis [Bernard Guidonis, in Baluze, I, 133; and likewise Prior Amalric Augerii, Baluze, 185; Muratori, Rerum Italicarum Scriptores III. 2, 488] on September 5, 1316, the first Sunday in September [Bernardus Guidonis; Souchon, p. 36 n.]. The Coronation had been twice postponed so that Count Robert of Poitou, who was now Regent of France, could be present. Count Charles of Valois, Alençon, Perche, Anjou and Maine, the brother of Count Philip the Regent, and Count Louis of Évreux, their uncle, held the reins of the horse on which the Pope rode in procession [Guillaume de Nangis, Chronicon, p. 428; Baluze, I, 794]

qui, mutato nomine, Johannes XXII papa vocatus, ibidem, ante Nativitatem beatae Mariae virginis, sua suscepit insignia, Karolo comite Marchiae, fratre Philippi regentis regna Franciae et Navarrae, eorumque avunculo Ludovico Ebroicensi comite frenum equi cui insidebat regentibus, ejusque festum decorantibus ipso die.

Giovanni Villani has it (Historia Universalis IX. 79, col. 483 Recanati) that John XXII was crowned at Avignon on the Nativity of the Virgin Mary, September 8, 1316. Well informed as he often is on Italian matters, Villani may safely be ignored on this point. Had John XXII been crowned on September 8, his many grants of September 5-7 would have been contestable, though the grants on those days specifically repair that very deficiency in the same appointments made before his Coronation.

On September 6 the newly-crowned pope bestowed a number of canonries and other benefices on members of the familiae of a number of Cardinals and servants of the King of France and his son [Fayen, Lettres de Jean XXII, nos. 3-13; 16-17]; the largesse was even more extensive on the next day, including a grant to Guillaume Prepositi, nephew of Cardinal Nicolas de Fréauville; Peter and Paul de Comite, cousins of Cardinal Napoleone Orsini [Bliss, Calendar of Papal Registers 2, p.124]; Pietro Colonna, nephew of Cardinal Pietro Colonna; Fentio Albertini, nephew of Cardinal Niccolò Alberti; Riccardo de Montinegro, nephew of Cardinal Jacobus Colonna; Aldebrandino de Comite, cousin of Cardinal Napoleone Orsini; Nicolaus Capoci, nephew of Cardinal Pietro Colonna; Lorenzo del Thedelgariis, nephew of Cardinal Giacomo Caetani Stefaneschi; Petrus, son of Bartholomeo de Papareschi and cousin of Giacomo Caetani Stefaneschi [Fayen, Lettres de Jean XXII, nos. 18-62 and 66-68]; though on September 8, the grants were only five in number [Fayen, Lettres de Jean XXII, nos. 71-75], though they included Giovanni Colonna, the nephew of Cardinal Pietro Colonna, and Matteo de Longis, the nephew of Cardinal Guglielmo de Longhi. On December 4, it was the turn of Percival de Fieschi, nephew of Cardinal Luca Fieschi [Fayen, no. 202]. Many of hese grants were very likely made from the rotuli provided by each cardinal for the new pope. And it must be admitted that there had been a twenty-eight month dry period during the Sede Vacante, when there was no papal largesse.

At the end of September, John XXII left Lyon and reached Avignon on October 2, where he established himself and the Roman curia [Baluze, I, 152, from Bernard Guidonis]. On December 13, 1316, showing that he intended to stay, he issued a Bull, Ad mensae elpiscopalis (Duhamel, 229-230), in which he ordered new construction work to begin on the episcopal palace at Avignon:

Ad mensae episcopalis ecclesiae Avinionensis augmentum, solicitis studiis, intendentes, illa paterna benevolentia promovemus, per quae status ejus gratis commodis augeatur. Volentes itaque ut Domus seu Palatium episcopale ipsius ecclesiae, prout decens et congruum fore dinoscitur, amplietur, eleemosinariae ac praepositurae novae ipsius ecclesiae Avinionensis, hospitia dictae domui seu palatio episcopali contigua, videlicet hospitium dictae elemosinariae cum hospitali, viridario, domibus et pertinentiis suis, prout protenditur....

This did not present a problem with the Bishop(-elect) of Avignon (1313-1317), who was the new Pope's nephew, Cardinal Jacobus de Via [Eubel, I, 15]. Upon Cardinal Jacobus' death on June 13, 1317, perhaps by "witchcraft", he was succeeded as cardinal by another papal nephew, Jacobus' brother Cardinal Arnauld de Via.

One of John XXII's early acts (April 7, 1317) was to canonize Louis d' Anjou, OMin., Bishop of Toulouse (1296-1297), the son of King Charles II of Sicily [Bernardus Guidonis, in Muratori, Rerum Italicarum Scriptores III. 2, 488; Baronius-Theiner 24, sub anno 1317, no. 9 pp. 45-46]. Louis had been Jacques Duèse's 'magister'. This was certainly pleasing to the House of Anjou and the Kings of France.

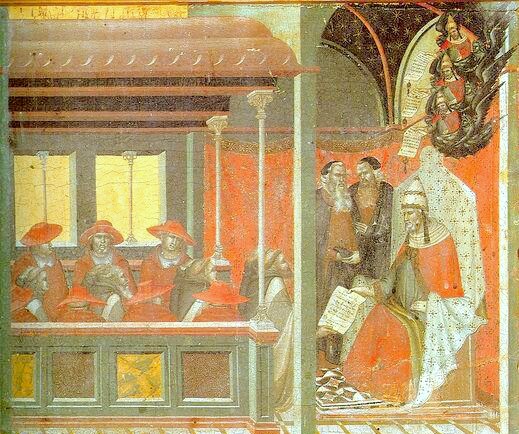

Pope John XXII and his Cardinals in Consistory

Bibliography

Giovanni Villani, Ioannis Villani Florentini Historia Universalis (ed. Giovanni Battista Recanati) (Milan 1728) [Rerum Italicarum Scriptores, Tomus Decimustertius]. Rose E. Selfe (translator), Selections from the First Nine Books of the Croniche Fiorentine of Giovanni Villani (Westminster 1896).

H. Geraud (editor), Chronique latine de Guillaume de Nangis de 1113 a 1300, avec les continuations de cette chronique de 1300 a 1368 nouvelle edition Tome premier (Paris: Jules Renouard 1843).

Carlo Cipolla (editor), Le opere di Ferreto de' Ferreti Vicentino I (Roma: Forzani 1908) II, 220- .. Max Laue, Ferreto von Vicenza. Seine Dichtungen und sein Geschichtswerk (Halle: Max Niemeyer 1884). [ca. 1295/1297-ca. 1337]

Nicholas, Bishop of Butrinto, Iter Italicum: Nicolai Episcopi Botrontinensis Relatio de itinere Italico Henrici VII. Imperatoris ad Clementem V., in Stephanus Baluzius, Vitae Paparum Avinionensium 2 (Paris 1693) columns 1143-1230.

Stephanus Baluzius [Étienne Baluze], Vitae Paparum Avinionensium 2 volumes (Paris: apud Franciscum Muguet 1693): "Sexta vita Clementis V, auctore Amalrico Augerii de Biterris Priore S. Mariae de Aspirano in diocesi Helenensi [Elne]" 95-112. "Prima Vita Joannis XXII, auctore Ioanne Canonico Sancti Victoris Parisiensis," 113-134. "Secunda Vita Ioannis XXII auctore Bernardo Guidonis Episcopo Lodovensi," 134-152. "Quinta Vita Ioannis XXII, ex appendice Ptolemei Lucensis," 173-178. "Sexta Vita Ioannis XXII, auctore Petro de Herentali, Canonico Praemonstratensi et Priore Floressiensi," 179-184.

Theiner, Augustinus (Editor), Caesaris S. R. E. Cardinalis Baronii, Od. Raynaldi et Jac. Laderchii Annales Ecclesiastici Tomus Vigesimus Quartus 1313-1333 (Barri-Ducis: Ludovicus Guerin 1872)

Joannes Dominicus Mansi, Sacrorum Conciliorum nova et amplissima collectio editio novissima Tomus Vicesimus Quintus (Venetiis: apud Antonium Zatta 1782).

Wilhelm Dönniges (Editor), Acta Henrici VII Imperatoris Romanorum et monumenta quaedam alia Medii Aevi Pars II (Berolini 1839). Iacobus Schwalm (Editor), Monumenta Germaniae Historia. Constitutiones et acta publica imperatorum et regum Tomus IV. inde ab a. MCCXCVIII usque ad a. MCCCXIII. Pars II (Hannoverae et Lipsiae: Hahn 1909-1911) nos. 777-812. [MGH] Robert Pohlmann, Der Römerzug Kaiser Heinrichs VII. und die Politik der Curie, des Hauses Anjou, und der Welfenliga (Nürnberg 1875). Oscar Masslow, Zum Romzuge Heinrichs VII.(Göttingen 1888).

Thomas Rymer, Foedera, Conventiones, Literae et cujuscunque generis Acta Publica inter Reges Angliae et alios quosvis... Tomus III (Londini: A. & J. Churchill, 1706).

Paul Maria Baumgarten, Untersuchungen und Urkunden über die Camera Collegii Cardinalium für die Zeit von 1295 bis 1437 (Leipzig 1898)

Eugène Déprez, "Recueil des documents pontificaux, conservés dans diverses archives d' Italie (XIIIe et XIVe siècles)," Quellen und Forschungen aus italianischen Archiven und Bibliotheken 3 (Rome 1900) 103-128; 255-307.

Bernard Guidone, "Vita Clementis Papae V," and "Vita Joannis Papae XXII," in Ludovicus Antonius Muratori, Rerum Italicarum Scriptores Tomus Tertius (Milan 1723), 673-684. [Bernard Guidonis [Gui], OP, of Royères in the Limousin, Bishop of Lodève (ca. 1261—1331): U. Chevalier, Repertoire I, 1919-1920]. Ignaz Hösl, Kardinal Jacobus Gaietani Stefaneschi. Ein Beitrag zur Literatur- und Kirchengeschichte des beginnenden vierzehnten Jahrhunderts (Berlin: Emil Ebering 1908). Heinrich Finke, Acta Aragonensia. Quellen zur deutschen, italianischen, franzosischen, spanischen, zur Kirchen- und Kulturgeschichte aus der diplomatischen Korrespondenz Jaymes II. (1291-1327) (Berlin und Leipzig 1908).

Bartolomeo Platina, Historia B. Platinae de vitis pontificum Romanorum ...cui etiam nunc accessit supplementum... per Onuphrium [Panvinium]... et deinde per Antonium Cicarellam (Cologne: Cholini 1626). Bartolomeo Platina, Storia delle vite de' pontefice edizione novissima Tomo Terzo (Venezia: Ferrarin 1763). Lorenzo Cardella, Memorie storiche de' cardinali della Santa Romana Chiesa Tomo secondo (Roma: Pagliarini 1792). Giuseppe Piatti, Storia critico-cronologica de' Romani Pontefici E de' Generali e Provinciali Concilj Tomo settimo (Poli: Giovanni Gravier 1767). 385-395 Ludovico Antonio Muratori, Annali d' Italia Volume 19 (Firenze 1827).

Jean-Baptiste Christophe, L' histoire de la papauté pendant le XIV. siècle Tome premier (Paris: L. Maison 1853) 78-175. Martin Bertrandy-Lacabane, Recherches historiques sur l' origine, l' élection, et le couronnement du pape Jean XXII (Paris: Treuttel et Würtz, 1854). Martin Souchon, Die Papstwahlen von Bonifaz VIII bis Urban VI (Braunschweig: Benno Goeritz 1888) 35-45. Herbert Hofmann, Kardinalat und kuriale Politik in der ersten Hälfte des 14. Jahrhunderts (1935).

Félix Rocquain, La papauté au Moyen Age (Paris 1881). F. Gregorovius, History of Rome in the Middle Ages, Volume V.2 second edition, revised (London: George Bell, 1906), Book X, chapter 6, pp. 598-607. St Clair Baddeley, Robert the Wise and his Heirs 1278—1352 (London: Heinemann 1897). Albert Huyskens, Kardinal Napoleon Orsini (Marburg 1902) [his professors were Grauert and Wenck]. Josef Asal, Die Wahl Johannes XXII. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte des Avignonischen Papsttums (Berlin 1910)

Joseph Francois Rabanis, Clément V et Philippe le Bel. Lettre à M. Charles Daremberg sur l'entrevue de Philippe le Bel et de Bertrand de Got à Saint Jean d' Angéli (Paris 1858). Edgard Boutaric, Clément V, Philippe le Bel et les Templiers (Paris: Victor Palmé 1874). Paul Lehugeur, Histoire de Philippe le Long, roi de France (1316-1322) I (Paris: Hachette 1897) 199-211. Sophia Menache, Clement V (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2002). C. Wenck, Clemens V. und Heinrich VII, die Anfänge des franzosischen Papstthums. Ein Beigrag zur Geschichte des XIV Jahrh. (Halle 1882). Ch.-V. Langlois, "Documents rélatifs à Bertrand de Got (Clément V)," Revue historique 40 (1889), 48-54. Edmond Albe, Autour de Jean XXII. Hughes Géraud, Éveque de Cahors: L'affaire des poisons et des Envoutéments de 1317 (Cahors-Toulouse 1904) [Géraud was accused, tried, and convicted of attempting to kill John XXII by poison and/or magic; his execution was precipitated by the sudden death of Cardinal Jacobus de Via].

J.-B. Martin, "L' origine de Jean XXII," Revue des questions historiques 19 (1876), 563-580. V. Verlaque, Jean XXII. Sa vie et ses oeuvres (Paris: Plon 1883). Fritz Ehrle, "Der Nachlass Clemens' V. und der in Betreff desselben von Johann XXII. (1318-1321) gefuhrte Process," Archiv für Literatur- und Kirchengeschichte 5 (1889), 1-166. Louis Guérard, "La succession de Clément V et le procès de Bertrand de Got," Revue de Gascogne 32 (1891) 5-20. The "Last Will and Testament" of Pope Clement V is also published (from a French manuscript) by G. Tholin (from material supplied by Dr. Berchon) in Archives historiques du Département de la Gironde 29 ((Bordeaux 1894) 356-376. L. Duhamel, "Les origines du palais des papes," Congrès archéologique de France. XLIXe Session (Paris:Champion 1883) 185-258.

Giulio Navone "Di un musaico di Pietro Cavallini in S. Maria in Trastevere e degli Stefaneschi di Trastevere," Archivio della società romana di storia patria 1 (1877) 219-239. Ignatz Hösl, Kardinal Jacobus Gaietani Stefaneschi (Berlin 1908) [Historische Studien LXI]. Arsenio Frugoni, "La figura e l'opera del cardinale Jacopo Stefaneschi," Rendiconti dell' Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, 3a s., 5 (1950), 397-424.

William Cornwallis Cartwright, On the Constitution of Papal Conclaves (Edinburgh 1878).