SEDE VACANTE 1492

July 25, 1492—August 11, 1492

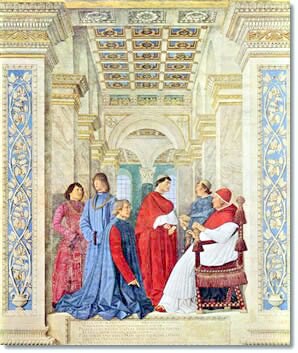

Platina is the kneeling figure,

Raffaele Riario is in blue, the future Julius II in the center.

and Pope Sixtus IV seated at the right.

No coins or medals were issued.

Raffaele Sansoni Galeotti Riario (May 3, 1461-July 9, 1521) was born at Savona, the son of Antonio Sansoni and of Pope Sixtus IV's sister Violentina. On December 10, 1477, while engaged in the study of law at the University of Pisa, he was created Cardinal Deacon of San Giorgio in Velabro by his uncle Pope Sixtus (1471-1484). He was 17. He was suspected of having had some connection with the Pazzi conspiracy, April 1478, through his uncle Count Girolamo Riario and Francesco Salviati, Archbishop of Pisa. Although he was arrested and imprisoned, his uncle the Pope had him freed and brought to Rome, where he was officially rehabilitated in consistory. He was named Chancellor of the Church [Cardella III, 210; according to Moroni 57, 171, he was named Vice-Chancellor], and in 1483 he became Camerlengo of the Holy Roman Church, a post he held until his death in 1521. He was loaded with benefices by Sixtus IV and Innocent VIII (1484-1492), including the administration and income of sixteen rich bishoprics (including eventually Tréguier in France (1480-1483), Pisa (as Apostolic Administrator, 1479-1499), Salamanca (as Apostolic Administrator, 1482-1483), Osma (as Apostolic Administrator, 1483-1493), Cuença (as Apostolic Administrator, 1479-1482), and Viterbo (as Apostolic Administrator, 1498-1506); he was also Abbot of Monte Cassino and of Cava.

Under Alexander VI, however, he was in disfavor. The greed for power and property on the part of the Borgia family made the Riarios a major target. Alexander's son Cesare coveted the holdings of the Riario family, and seized the city of Forlì and also Imola. Riario fled to France and took up his bishopric of Tréguier. On his return in September of 1503 he was appointed Bishop of Albano (in November, 1503) and was consecrated bishop on April 9, 1504 by Pope Julius II personally (another nephew of Sixtus IV). In 1507 he was promoted to the bishopric of Sabina, and on July 7, 1508, became Apostolic Administrator of Arezzo. Julius II made him Cardinal Bishop of Ostia, Porto, and Velletri on September 22, 1508. . He participated in five conclaves, including the conclaves of 1484, 1492, 1503 that elected Pius III and the one that elected Julius II, and that of 1513.

In 1517, he was involved in the conspiracy of Cardinal Alfonso Petrucci against the life of Pope Leo X (also involving Cardinals Soderini and Sauli) and was arrested (May 29) and incarcerated in the Castel S. Angelo (De Grassis, p. 48). Trials were held. The ambassadors of England, France and Spain interceded. The College of Cardinals intervened on his behalf when it appeared that he might be stripped of all of his benefices, degraded from the cardinalate, and condemned to death. On July 24, he was released from confinement and brought to the Vatican; after he swore an oath, he was admitted to the presence of the Pope (De Grassis, p. 57). After he confessed to the Pope in a lengthy speech and begged pardon, which the Pope was pleased to grant, with a huge fine, whose value changed repeatedly, and the confiscation of his palace at S. Lorenzo in Damaso (the Cancelleria). He was restored to the bishopric of Ostia at Christmas, 1518, and his fine was cancelled. He died in 'retirement' in Naples.

Paris de Grassis, Papal Master of Ceremonies, records his death in 1521 (p. 86):

Die nona julii mortuus est cardinalis Sancti Georgii, Raphael Riarius Savonensis, decanus colegii et episcopus ostiensis, qui cum esset aetatis suae anno decimonono creatus est a Sixto cardinalis, demum in vicesimo secundo camerarius in quo mansit annos viginti novem, et sic anno sexagesimoprimo vel circa obiit Neapoli. . . .

The Dean of the College of Cardinals in 1492 was Cardinal Roderigo de Borja (1431-1503), Bishop of Porto, nephew of Pope Calixtus III. The holder of the Suburbicarian Bishopric of Ostia, which normally went with the office of Dean of the Sacred College, was Cardinal Giuliano de Rovere, a nephew of Pope Sixtus IV. When Cardinal Borgia became Pope Alexander VI, the office of Dean went to Oliviero Carafa, who was Suburbicarian Bishop of Sabina.

The Governor of the Apostolic Palace was Gundisalvus Fernandez de Heredia, Archbishop of Tarragona (1490-1511), who had been instrumental in bringing about peace between Innocent VIII and the King of Naples.

The Secretary of the Sacred College and Secretary of the Conclave was Octavianus de Fornariis, a cleric of the Diocese of Genoa. He was elected by the Sacred College of Cardinals , due to a vacancy caused by the resignation of Joannes Lopis. His election was registered with the Apostolica Camera on August 11, 1492, at the conclusion of the Conclave [Eubel II, p. 30, no. 544].

Innocent VIII, Naples and France

In 1485, under the influence of Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere, Innocent involved himself in the politics of the Kingdom of Naples. Some of the more conservative of the barons of Naples were unhappy with the progressive and modernizing policies being instituted and expanded by Ferdinand I (Ferrante). Naturally, many of the churchmen of Naples, steeped in traditional Catholic conservatism, supported the barons. There were some notable exceptions, Cardinal Oliviero Carafa and his family among them. Innocent's decision placed him in the French camp, as far as the succession to the throne of Naples was concerned. Guliano della Rovere was satisfied with that, since the French had helped to liberate his native Savona and the Republic of Genoa from the clutches of the Visconti of Milan. He had also been Apostolic Legate in France and was the first Archbishop of Avignon, created by his uncle Sixtus IV in 1475..

Sultan Djem and Cardinal d'Aubusson

On May 31, 1492, Pope Innocent and the College of Cardinals went to S. Maria del Popolo to receive the Ambassador of the Grand Turk, Bayezid, who was bringing the gift of the Holy Lance to the Pope [Giovanni Burchard, p. 484 ed. Thuasne, Vol. I]. On Monday, July 16, it was placed in St. Peter's Basilica, where the Veronica was kept. This gift from the Sultan was in acknowledgment of the great favor which the Pope was doing him. The son of Mohammed II the Conqueror (died 1481), both Bayezid and his younger brother Djem struggled for the succession to the throne. When Djem was defeated in the siege of Konya, he asked for protection from the Knights of S. John, which was granted. He offered the Knights a permanent peace between the Ottoman Sultanate and Christendom, if the Knights would help him overthrow his brother Bayezid. Bayezid made a counter-offer of a large amount of money to keep Djem a prisoner. Djem was sent to France, to a castle belonging to the Grand Master, Pierre D'Aubusson, who transferred him to the custody of Pope Innocent in March, 1489. Not surprisingly, in the same month, Pierre d'Aubusson was made a cardinal (in contravention of the Electoral Capitulations of 1484, which limited the number of cardinals to twenty-four). To keep Djem in custody, Bayezid paid the Pope 120,000 crowns of gold and an annual subsidy of 45,000 ducats [Stefano Infessura, Diaria, sub anno 1489, p. 240-242 Tommasini; see also the Commentarii of Guillelmus Caoursin, Vice-Chancellor of the Knights of S. John of Rhodes, in Thuasne's edition of Burchard, Volume I, 528-546]. This was the first occasion on which a pope entered into a diplomatic agreement with the Ottoman Empire, and accepted an annual retainer. The knowledge of it made it almost impossible for the Pope to continjue to sell the idea of a Crusade. During the second week of July, 1492, however, the Cardinals, anticipating the death of Innocent VIII, sent Djem to the Castel S. Angelo [Infessura, p. 274]. This may well have been for his own protection, given the murderous unruliness of the crowds of Rome in the last months of Innocent VIII's reign.

Death of Pope Innocent

On Thursday, June 14, the new English ambassador, John Sherwoode, the Bishop of Durham, entered the city and was received by the Cardinals. The two Spanish Orators, Bernardino Carvajal, the Bishop of Badajoz (1489-1493), and Johannes Ruiz de Medina, the Bishop of Astorga, became embroiled in a struggle over precedence with the outgoing British Orator, Johannes Gilius de Luca, which required the intervention of the Master of Ceremonies, Giovanni Burchard [Burchard, p. 490 T].

Already by the 16th of July, the Florentine Ambassador in Rome, Filippo Valori, had informed his government that Pope Innocent VIII (Cibò), already ill with the fever, had contracted a catarrh (letter in Thuasne's edition of Giovanni Burchard, Diarium, p. 568; Petruccelli, 343). The doctors did not give him much time, and the College of Cardinals had inventoried the papal jewels and had called in the Count of Petigliano and his men. The Vice-Chamberlain and Governor of Rome, Bartolomeo Moreno, anticipating the robbery that took place during the general disorders that accompanied the death of popes, had his familia and his valuables removed to the house of one of the Conservatori of Rome, Ludovico Matthei, where greater security was available. The disorders were so extensive, replete with robbery and murder, that there was hardly any governmental control, not by the Senator, nor by the Vice-Chamberlain, nor by the other Officiales of Rome [Infessura Diaria, p. 275-276 Tommasini]

On Sunday, the 22nd, Prospero Colonna and Giovanni Giordano, son of Virginio Orsini, along with a number of Roman barons (who were meeting at the house of Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere, Bishop of Ostia) held a meeting with the Officiales of Rome at the Palazzo dei Conservatori. They offered their property and their services pro salute populi, in anticipation of the death of the pope. The Conservatores and citizens offered in return whatever it was that they could offer. What the point of the meeting was, remarks Infessura, is thus far unclear. One may well imagine that Rovere was preparing for a struggle for the papacy against Rodrigo Borgia, and was seeking to solidify the entire Roman interest, if possible, behind his candidacy [letter of Filippo Valori, in Thuasne's edition of Giovanni Burchard, Diarium, p. 571].

On Monday, the 23rd of July, Vallori reported that two marriages had taken place at the Palace of Cardinal della Rovere, one of the nieces of Virginio Orsini with the son of Prospero Colonna (neither of whom was yet six years of age; the other niece married the nephew of Cardinal della Rovere. Obviously Della Rovere was making preparations. On July 16, the pope was reported in extremis. The pope no longer wanted to eat, but he did distribute 48,000 ducats to his relatives, with the permission of the Cardinals. On the 23, with everyone just waiting for the end, the gossip (reported Valori) was mentioning as papabili Carafa, da Costa, Ardicino de la Porta, Piccolomini and Borgia. At the same time, Pietro Alamanni, the Ambassador of Florence in Naples, wrote that he had had an audience with the King of Naples, who showed no interest in any particular cardinal. Later that day, his Ambassador to Rome, Pontano remarked that King Ferdinand had been estranged from the Roman Church for six years, and that in that time none of the cardinals had shown himself favorable to him [Petruccelli I, pp. 347-348].

On July 24, the College of Cardinals appointed Cardinal Rafaelle Riario to see to the various security arrangements for the Borgo and the Vatican Palace [letter of Filippo Valori, in Thuasne's edition of Giovanni Burchard, Diarium, p. 572-573].

Pope Innocent died on the evening of Wednesday, July 25, 1492, according to the Diary kept by Giovanni Burchard, the Papal Master of Ceremonies (Burchard, 194G 491T; Petruccelli, 346):.

Die 25 julii, in die Sancti Jacobi, sexta vel quinta hora noctis, mortuus est Innocentius Papa Octavus, cuius anima requiescat in pace. ....

Cardinal Riario, the Camerlengo, sought to appoint a Marshal to take charge of the security of the city and its bridges, but the city officials resisted him on the grounds that the office was elective. Riario gave way, but four Roman leaders made an unofficial and illegal decision to elect officials who were acceptable to the Camerlengo, over the objections of the Captains of the Rioni (Burchard, 194G). Ultimately the ambassadors of the various powers agreed jointly to protect the security of the conclave.

On the morning of Thursday, July 26, a Congregation of the Cardinals was held, and immediately the matter of Federigo Sanseverino was then brought up. Then the Commandant of the Castel S. Angelo swore obedience to the Sacred College, according to the custom. The Cardinal of Benevento, Lorenzo Cibò (the late Pope's nephew and one of the Palatine cardinals), stood surety for him. Then the Venetian Ambassador was admitted; he presented a letter of condolence from the Signoria and made a speech on the same topic. When the business ws settled, the body of the deceased Pope was transferred to S. Peter's Basilica, accompanied by the Cardinals whom he had created. The Novendiales were scheduled to begin on Saturday, July 28 [letter of Filippo Valori, in Thuasne's edition of Giovanni Burchard, Diarium, p. 575].

The Sanseverino Case

Federigo Sanseverino (aged 17), son of Conte Roberto di Cajazzo in the Kingdom of Naples, the General of the Papal army, had been named a cardinal in pectore by Innocent VIII on March 9, 1489, but his name had not been made public for the next three years and four months. Innocent had ordered that the cardinals he had named in pectore should be allowed to participate in the forthcoming Conclave. On the 26th of July [Eubel II, p.50 no. 541, from the Acta Cameralia, makes it July 24; if this is correct, the demand was made before the death of the Pope, not after; Infessura says, qui per aliquot dies ante steterat cum Fracasso, eius fratre, apud S. Anastasiam extra Porta Sancti Pauli...et instabat pro cardinaltu sibi promisso ab Innocentio et toto Collegio], before the body of the pope was removed from his palace, the Cardinals held a meeting about the admission of a new cardinal, Federico de Sanseverino, the son of Robert, who was at S. Anastasio outside Porta S. Paolo with an army, demanding the cardinalate promised to him and his son by Innocent VIII and the Sacred College. Under such pressure, and with Cardinal Ascanio Sforza working on his behalf inside the Sacred College, he was admitted and given a place in the conclave, and even was allowed to help carry the body of the dead pope to St. Peter's. Burchard, however, considered him quite unsuitable for a cardinalate. On August 3, the Patriarch of Venice, Maffeo Gherardo, appeared in Rome with similar claims, which, at a meeting of the Cardinals on August 4, were also allowed. [Burchard, 194G; Eubel II, p.50 no. 543, from the Acta Cameralia].

On Saturday July 28, in the fifth hour of the night, the Vice-Chamberlain, Bartolomeo Moreno, Archpriest of Vignola, fled from the City and took refuge at Castro Vetrallae [Infessura, Diaria, p. 278 T].

Preparations of Cardinal Borgia

It is said (Infessura, p. 282) that even before the conclave opened, Cardinal Borgia sent four mules laden with silver to the palace of Cardinal Ascanio Sforza to secure his vote. Sforza, who had considerable hopes for his own election, only went over to Borgia—and then with enthusiasm—when his own success proved impossible. In fact only five or six cardinals were not included in the generosity of Cardinal Borgia: Caraffa, Piccolomini, della Rovere, da Costa and Zeno; one should also include Cardinal de' Medici, who voted for Piccolomini.

Cardinals

The novendiales were completed on August 5. On August 6 the Conclave began. Twenty-three cardinals entered the Vatican Palace. Burchard (p. 194 G) provides the names of all of the cardinals. See also Eubel, Hierarchia catholica editio secunda (Monasterii 1923), p. 22 n. 4. Another list of the participants is provided by Michele Ferno of Milan (quoted by Thuasne, p. 579-580). There is a slightly older list, also from the Milan archives (Pastor V, 532-533), of the twenty-two cardinals alive slightly before March, 1491 (when Cardinal Barbo died). It claims that there were six votes firmly for Cardinal Ascanio Sforza and four others who were leaning his way. Sixteen votes were needed to elect.

- Roderigo Borgia, Cardinal Bishop of Porto, Vice-Chancellor of the Holy Roman Church. Dean of the College of Cardinals Nephew of Calixtus III.

- Oliviero Carafa (aged 62) [Neapolitanus], son of Francesco Carafa, grandson of Carlo "Malizio" Carafa, nephew of Diomedes, first Count of Maddaloni (d. 1487); his mother was Maria Origlia, daughter of Giovan Luigi, Signore di Vico Pontano, and Anna Sanseverino. Cardinal Bishop of Sabina (1483-1503). Legum Doctor (Naples). Apostolic Administrator of Salamanca (1491-1494). Legatus a latere to France in 1470. He had commanded the papal navy against the Ottoman Turks from 1471 to 1474. Chamberlain of the Kingdom of Naples (1477-1478). Protector of the Ordo Praedicatorum, from 1478. Abbot commendatory of S. Maria de Cava, from 1485. He was a staunch supporter of Ferrante of Naples. It was Oliviero Carafa who erected the famous statue of Pasquino outside his house near the Piazza Navona Died January 20, 1511. "Neapolitanus" See: Alfred de Reumont, The Carafas of Maddaloni: Naples under Spanish Dominion (London 1854) 138-141.

- Giuliano della Rovere (aged 38) [Albissola, near Savona], son of Raffaele della Rovere, brother of Sixtus IV, and Theodora Manerola. Cardinal Bishop of Ostia and Velletri (1483-1503). Cardinal Bishop of Sabina (1479-1483). Earlier he had been Cardinal Priest of S. Pietro in vincoli (1471-1479). Bishop of Bologna (1483-1502). Archbishop of Avignon (1475-1503); Major Penitentiary (1476-1503). Apostolic Legate to France, 1480-1482. [Eubel II, p. 43, no. 423 and 426; p. 44, no. 454] In civitate Avinionensi et Comitatu Venaissini Vicarius, et Sedis Apostolicae Legatus [Bullarium Civitatis Avinionensis (Lugduni, 1657), p. 46 (June 17, 1491)]. "S. Petri"

- Giovanni Battista Zeno [Venetus], Cardinal Bishop of Tusculum (Frascati) (1479-1501), previously Cardinal Priest of S. Anastasia (1470-1479) , and Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Portico (1468-1470). Nephew of Paul II.

- Giovanni Michaeli (Michiel), Veronensis, Cardinal Bishop of Palastrina, Cardinal of S. Angelo in Pescheria. Legatus a latere in the Patrimony of S. Peter [Eubel II, p. 48 no. 520 (June 5, 1486)]

- Georgio da Costa (aged 86) [Ulixpoensis], Cardinal Bishop of Albano. Archbishop of Lisbon (1464-1500). Died September 18, 1508

- Geronimo Basso della Rovere (aged 58), Recanatensis, son of Giovanni Basso, Count of Bistagno; and Luchina della Rovere, sister of Sixtus IV. Cardinal Priest of S. Crisogono (1479-1492). Bishop of Recanati (1476-1492). Nephew of Sixtus IV.

- Domenico della Rovere (aged 50), [Tarentasiensis], Cardinal Priest of S. Clemente. Bishop of Turin (1482-1501). Died April 22, 1501.

- Paolo Fregosi (Foscari) (aged 62), [Genuensis], son of Battista I, Doge of Genoa. He became Archbishop of Genoa in 1453, at the age of 26, with the help of his brother Peter. He was Doge of Genoa, in 1462, 1464, and 1480. Cardinal Priest of S. Sisto. He died in Rome on March 22, 1498 [Eubel II, p. 53 no. 600].

- Giovanni de' Conti (aged 78), Consanus, Cardinal Priest S. Vitale (1489-1493), formerly Cardinal Priest of of SS. Nereo ed Achilleo.(1483-1489). He died on October 21, 1493, of the plague [Stefano Infessura, Diario, p. 294 ed. Tommasini].

- Giovanni Jacopo Sclasenatus (Schiaffinati) (aged 40), Cardinal Priest of S. Cecilia (1484-1491), Cardinal Priest of S. Stefano in Monte Caelio (S. Stefano Rotondo) in commendam (1484-1491). Bishop of Parma (1482-1497) "Parmensis"

- Lorenzo Cibo, [Genuensis] Cardinal Priest of S. Marco (1491-1503), previously Cardinal Priest of S. Susanna (1489-1491) Archbishop of Benevento (1485-1503) "Beneventanus"

- Ardicinus de la Porta (58) [Novara], Cardinal Priest of. SS. Giovanni e Paolo (1489-1493). Bishop of Aleria (1475-1493). Doctor in utroque iure. "Aleriensis"

- Antonio (Antoniotto) Pallavicini (aged 51) [Genuensis], son of Balbiano Pallavicini and Catherine Salvago. Cardinal Priest of S. Anastasia (1489-1507). Bishop of Ventimiglia (1484-1486) Bishop of Orense (1486-1507) Papal Datary of Innocent VIII, 1484-1489. He died on September 10, 1507 [Gulik-Eubel Hierarchia catholica III (1923), p. 124 n. 2] "Auriensis"

-

Francesco Todeschini-Piccolomini, Senensis, son of Nanni Todeschini, the richest man in Siena, and Laodamia Piccolomini, sister of Pius II; he was adopted by Pius. Cardinal Deacon of S. Eustachio. He was Administrator, then Bishop of Siena (1460-1503). Protector of the Camaldolese. He was also Protector of the Canons Regular of S. Augustine of the Most Holy Savior by 1485 [ Bullarium Canonicorum Regularium Congregationis Sanctissimi Salvatoris (Romae 1733), pp. 102-108, nos. 43-49] He had been Rector of the Marches of Ancona from 1460-1463. He was Vicar of Rome, when Pius II went on Crusade in 1464. He died, as Pius III, on October 18, 1503. Nephew of Pius II. Doctor of Canon Law (Perugia).

- Raffaele Sansoni Riario [Savona], son of Antonio Sansoni and Violante Riario, sister of Cardinal Pietro Riario. He built a Renaissance palace next to the Church of S. Lorenzo in Damaso, which became the residence of the Chancellor S.R.E. Cardinal Deacon of S. Giorgio in Velabro (Velum Aureum), Cardinal Camerlengo; Cardinal Priest of S. Sabina, Cardinal Priest of S. Lorenzo in Damaso (1480-1503) [Eubel II, p. 19 no. 22]. Bishop of Albano (November 29, 1503) [Gulik-Eubel III, p. 3 no. 6]. Apostolic Administrator of Pisa (1479-1499), Apostolic Administrator of Salamanca (1482-1483), Apostolic Administrator of Osma (1483-1493) At the Conclave of 1492, Sancti Georgii is mentioned last among the 23 cardinals who entered Conclave, in the Diarium of the Master of Ceremonies, Giovanni Burchard [p. 194 ed. Gennarelli]; Eubel II, p. 22 n. 4 lists him after Senensis and before Savelli.

- Giovanni Battista Savelli (aged 70 ?), Cardinal Deacon of S. Nicola in Carcere Tulliano (ca. 1483-1498) {Eubel II, p. 67], formerly of SS. Vito e Modesto in Macello Martyrum (1480-ca. 1483) [Eubel II, p. 68].

- Giovanni Colonna (aged 36), Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Aquiro. Apostolic Administrator of Rieti (1480-1508). Died October 26, 1508.

-

Giovanni Battista Orsini (aged 42 ?), son of Lorenzo Orsini (son of Orso Orsini, Signore di Monterotondo, a descendant of Matteo, brother of the celebrated Cardinal Napoleone Orsini); and Clarice Orsini, daughter of Carlo, Signore di Bracciano and Geronima Paola Orsini dei Conti di Tagliacozzo. Canon of the Vatican Basilica, Cleric of the Apostolic Camera, Protonotary Apostolic, Canon of the Lateran Basilica, Vice-Rector of the University of Firenze (from 1475), Abbot commendatory of Farfa (from 1483). Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria Nuova (1489-1493), previously Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Domnica (1483-1489). He was subsequently Cardinal Priest of SS. Giovanni e Paolo (1493-1502). Apostolic Administrator of Taranto (1490-1498). He detested Venice. He was summoned to the Vatican Palace by Alexander VI on January 3, 1503, arrested, and sent to the Castel S. Angelo, where he died, perhaps of poison, on February 22, 1503 [Eubel II, p. 19] (others say 1502)

- Ascanio Maria Sforza Visconti (aged 37), son of Francesco Sforza, Duke of Milan (1401-1466); and Bianca Maria Visconti, illegitimate daughter of Filippo Maria I Visconti, Duke of Milan and Agnese del Majno. Cardinal Ascanio was the younger brother of Ludovico "Il Moro", Duke of Milan and Conte di Pavia (1494-1499). Cardinal Deacon of SS. Vito e Modesto in Macello Martyrum (1484-1505). Legate in Bologna (1490). He was, of course, an enemy of the French, the Aragonese of Naples and Cardinal della Rovere.

- Giovanni de' Medici (aged 18) [Florentinus], Cardinal Deacon of Sta. Maria in Dominica. On May 11, 1492, he was made Legatus a latere for Tuscany and Florence [Eubel II, p. 50 no. 540]. See Burchard, Diarium sub anno 1492, pp. 160-164, 166-175 ed. Gennarelli. On March 12, he had gone to Rome, and on Sunday, May 20, 1492, he had returned to Florence; Lorenzo the Magnificent had died on April 8 [Luca Landucci, Diario fiorentino p. 64-65 ed. del Badia]

-

Federico Sanseverino (aged 17), fifth son of Roberto (1418-1487) Conte di Caiazzo (1483); Conte di Colorno, Marchese di Castelnuovo Tortonese (1474), Signore di Lugano (1479), etc (whose grandfather Bertrando was Grand Constable of the Kingdom of Naples).; and Elisabetta Montefeltro, illegitimate daughter of Federico III Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino. Federico Sanseverino was Cardinal Deacon of S. Teodoro. Giovanni Burchard, the Papal Master of Ceremonies [p. 194 ed. Gennarelli] complains that he was not a bishop or a protonotary, but only a subdeacon. He was Apostolic Administrator of the Diocese of Maillezais (Malleacensis) in the Vendée, from 1481 [Eubel II, p. 184], not Maizellais (as in Salvador Miranda) or Marseille (as in G-Catholic) or Malaga (as in Cardella III, p. 243). He was, or became, a mortal enemy of Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere (Julius II). His connections were French and Milanese (several of his father's titles). His eldest brother, Gianfrancesco, was a general in the armies of the Duke of Milan and of the King of France. The second-oldest brother, Antonio Maria (d. 1497) served in the French army at Monferrato. Another brother Gaspare (Fracassa) was in the service of the Sforza. His fourth brother Galeazzo died in the Battle of Pavia, 1525.

-

Maffeo Gherardi, OSBCamald. (aged 86), son of the Venetian nobleman Johannes Girardus, provisor and orator of the Venetian Republic, and Christina Barbarigo; he had a brother Hieronymus, who was Doctor utriusque iuris. Pope Nicholas calls Maffeo genere nobilis. Patriarch of Venice (1468-1492), elected after having failed to win election in three previous vacancies. Before his election as Patriarch, he was Vicar General of the Camaldolese Order [Salvador Miranda wrongly labels him "Abbot General of the order". Gherardi was never the Prior General of the Camaldolese; that honor belonged to Mariotto de Allegris of Arezzo from 1453 to 1478: Annales Camaldulensium 7, p. 236 and 298. Mariotto's successor as 44th Prior General was Hieronymus Griffonius of Florence, who died in 1480, and he was followed by Petrus Delphinus of Venice. Michaele Ferno of Milan, who wrote a narrative of the Sede Vacante of 1492, says of Maffeo Gherardi: tertium explebat locum Camaldulensis ordinis (Thuasne's edition of Giovanni Burchard's Diarium, I, p. 580)]. Gherardi was Abbot of S. Michael de Muriano (1448-1468) [Annales Camaldulensium 7, p. 223]. He was Cardinal in pectore from 1489-1492, and had never received the red hat or been given a title. He is said, however, to have been named Cardinal Priest of SS. Sergio e Baccho (which was, however, a deaconry).

He arrived in Rome on August 3, 1492, and spent the night at the monstery of S. Maria del Popolo. His entrance into Rome is also noticed in a letter of August 3, written by Filippo Valori, the Orator of Venice [Thuasne's edition of Giovanni Burchard, Diarium, p. 577]. On August 4 he was escorted to the Sacristy of the Vatican Basilica by Cardinals Savelli and Orsini, both Cardinal Deacons, where the Cardinals received him and exchanged the kiss of peace [Eubel II, p. 50 no. 543, from the records of the Apostolica Camera].

Salvador Miranda states, "At the death of Pope Innocent VIII, he arrived in Rome on August 3, 1492 and was received by Cardinal Giovanni Battista Orsini, who accompanied him the following day to the sacristy of the patriarchal Vatican basilica, where the Sacred College of Cardinal was gathered; he was recognized as a cardinal at the instance of the Council of Ten of Venice and published; it could be that at this time he received the title of Ss. Nereo ed Achilleo." This is completely impossible, since the Sacred College has no such authority to grant titles, even during the Sede Vacante. If he had a title, it would have had to come from Innocent VIII, or perhaps from Rodrigo Borgia after the Conclave. The records of the Apostolica Camera, however, do not give him a title when they register his entry into Rome or into the Conclave, nor is there a record of his being assigned a title during the month following the Conclave. Eubel does not list him at the titulus SS. Nerei et Achillei at all [p. 64], but at the deaconry of SS. Sergio e Bacco [p. 67]—for unstated reasons. Maffeo Gherardi died on September 14, 1492, a month after the Conclave ended, on his way back to Venice, at Interamna (Terni), suffering ex dysenteria et lienterica [Annales Camaldulensium 7, p. 341, from Pietro Delfini, Prior General of the Camaldolese, Epistolae Lib. XI, no. 61 and no. 65]. The source of Miranda's information about the Venetian influence is Stefano Infessura's diary, but Infessura only says, quem dixerunt fuisse factum cardinalem instantibus Venetiis per Innocentium. Clearly the Venetian pressure was applied to Pope Innocent in 1489, not to the Cardinals during the Sede Vacante of 1492.

Four cardinals did not participate, two Spaniards and two Frenchmen.

- Luis Juan del Milà y Borja (aged 60/62), Cardinal Priest of SS. IV Coronati (1456-1508?), Bishop of Lérida (1459-1508?), previously Bishop of Segorbe (1453-1459), Provost of Valencia. He had not been in Rome in the previous 25 years.

- Pedro González de Mendoza (aged 64), son of the Marquis de Santilanna; and Catalina de Figueroa, daughter of don Lorenzo Suarez de Figueroa, Señor de Feria y Cafra. Cardinal Priest of S. Croce in Gerusalemme (1478-1495), in succession to Cardinal Angelo Capranica. He was previously Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Domnica (1473-1478), and was promoted Cardinal Priest on July 6, 1478 [Eubel II, p. 41 no. 390]. He had been Chancellor of the Kingdom of Castile and Leon. Archbishop of Toledo (1482-1495). Titular Patriarch of Alexandria (1482-1495). He was also Bishop of Siguenza (1467-1495). He had earlier been Bishop of Calahorra (1453-1467). He died on January 11, 1495, notice of which was received in the Apostolic Camera on January 29 [Eubel II, p. 51 no. 572; Burchard Diarium Vol. 2, p. 237 Thuasne]. See Pedro Salazar de Mendoza, Crónica de el gran cardenal de España don Pedro Gonçalez de Mendoça (Toledo 1625). Abelardo Merino Alvarez, El Cardinal Mendoza (1942). Ramon Lacadena y Brualla, El gran cardenal de España (don Pedro González de Mendoza) (1942).

- André d'Espinay (aged 41), a Breton, the son Richard, Sieur d'Espinay, Grand Chamberlain of Brittany; and Beatrice, sister of Arthur (Artus) de Mont-Auban, Archbishop of Bordeaux, who was actually a Breton. Cardinal Priest of SS. Silvestro e Martino ai Monti, Archbishop of Bordeaux (1479-1500), and Lyon (1488-1500), Peer of France. Licentiate in canon law. He was granted the Abbey of Ste Croix in Bordeaux in 1490 or 1491. He accompanied Charles VIII in his Italian campaign, and actually took up arms and fought. He died in Paris on November 10/11, 1500; his funeral inscription says November 10 [Eubel II, p. 55 no. 635]. [Gallia christiana 2, pp.844-846]

- Pierre d'Aubusson (aged 68), Cardinal Deacon of S. Adriano al Foro (1489-1503). Grand Master of the Order of S. John of Jerusalem (1470-1503). He died on July 3, 1503 at Rhodes, the headquarters of the Knights of S. John [Eubel II, p. 56, no. 659]. See: Abbe de Vertot, History of the Knights Hospitallers of S. John of Jerusalem Volume II (Dublin 1818) pp. 209-236. John Taaffe, History of the Holy, Military, Sovereign Order of St. John of Jerusalem III (London 1852). L. De Caro, Storia dei Gran Maestri e Cavaliere di Malta II (Malta 1853), 330-351 and 465-476.

Election of Cardinal Borgia

On Wednesday, August 1, Filippo Valori wrote to the Signoria of Florence that the pratticà in Rome was intense. The Orators of Venice had been instructed to cooperate with the Florentines. The Florentines also had a warm regard for Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere, and the Venetians were working on cardinals to put their votes at the disposal of della Rovere, who was apparently promoting the Cardinal of Lisbon, Giorgio da Costa. Various other cardinals were mentioning Oliviero Carafa, the Cardinal of Naples; the Venetian Giovanni Battista Zeno, the Cardinal of S. Maria in Porticu; and Ardicinus de la Porta of SS. Giovanni e Paolo. Zeno and del la Porta were either first-round compliments, however, or else trial balloons. The real candidates were Borgia and della Rovere (unless Rovere intended, as he had done successfully in 1484, to get a weak pawn elected, through whom he could rule). But the candidacies of Carafa and da Costa are even more emphatically stated in Valori's letters of August 3 and August 4.

The last day of the Novendiales was on August 5. The Funeral Oration was pronounced by Msgr. Leonello Cheregato of Venice, Bishop of Concordia (1488-1506).

The Conclave began on Monday, August 6, 1492, at the Vatican Basilica, with the Mass of the Holy Spirit sung by Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere, Bishop of Ostia. The oration de pontifice eligendo was delivered by Bernardino Carvajal, Bishop of Badajoz, Ambassador of Ferdinand of Aragon [Novaes, Introduzione I, p. 281]. The cardinals were then sequestered in the Vatican Palace [Burchard, Diarium p. 194 ed. Gennarelli].

On Friday, the 10th of August, the Ambassador of Florence wrote that there had been three scrutinies, with no result. Those would have been the scrutinies on August 7, August 8, and August 9. The most votes were going to Borgia, Carafa of Naples and the Cardinal of Lisbon, da Costa, though none of them was close to the sixteen votes needed for canonical election. A Vatican manuscript [Vat. Arch. Miscell. Arm. XV, vol. 109, fol. 43v-48r, published by V. Schweitzer, Historisches Jahrbuch 30 (1909)] provides a detailed list of the votes in each of the scrutinies (not, apparently, including the accessio), both who was voting and for whom he was voting. The scrutiny was a preference poll, in which one could vote for several candidates. Cardinal Ascanio Sforza, for example, regularly voted for 4 or 5 candidates on a scrutiny. On August 7 the voting had gone [La Torre, 89, and foldout plate]:

| Cardinal | Votes for |

|---|---|

| Borgia (the Vice-Chancellor) | 7 |

| della Rovere (Cardinal S. Pietro) | 5 |

| Carafa (Neapolitanus) | 9 |

| Zeno (S. Maria in Porticu) | 2 |

| Michiel (S. Angeli) | 7 |

| da Costa (Ulixibonensis) | 7 |

| Basso della Rovere | 3 |

| Fregoso (Januensis) | 1 |

| Conti | 1 |

| della Porta | 5 |

| Piccolomini | 6 |

| Savelli | 1 |

| Total | 54 |

In the second scrutiny, on August 8, the votes were [La Torre, 90, and foldout plate]:

| Cardinal | Votes for |

|---|---|

| Borgia (the Vice-Chancellor) | 8 |

| della Rovere (Cardinal S. Pietro) | 5 |

| Carafa (Neapolitanus) | 9 |

| Zeno (S. Maria in Porticu) | 5 |

| Michiel (S. Angeli) | 7 |

| da Costa (Ulixibonensis) | 8 |

| Basso della Rovere | 4 |

| Fregoso (Januensis) | 1 |

| Pallavicini (S. Anastasiae) | 2 |

| della Porta | 5 |

| Piccolomini | 4 |

| Savelli | 2 |

| Riario (Camerarius) | 3 |

| Orsini | 1 |

| Ascanio Sforza | 1 |

| Total | 65 |

The third Scrutiny, on August 9, produced the following result [La Torre, 91, and foldout plate]:

| Cardinal | Votes for |

|---|---|

| Borgia (the Vice-Chancellor) | 8 |

| della Rovere (Cardinal S. Pietro) | 6 |

| Carafa (Neapolitanus) | 10 |

| Zeno (S. Maria in Porticu) | 5 |

| Michiel (S. Angeli) | 10 |

| da Costa (Ulixibonensis) | 7 |

| Basso della Rovere | 3 |

| Fregoso (Januensis) | 1 |

| Conti | 2 |

| della Porta | 4 |

| Piccolomini | 7 |

| Savelli | 1 |

| Riario (Camerarius) | 1 |

| Colonna | 1 |

| Domenico della Rovere | 3 |

| Pallavicini | 1 |

| Gherardo (Venetiarum) | 3 |

| Total | 73 |

In three days of balloting, Borgia's candidacy did not seem to be advancing. He was not attracting additional votes. His core of supporters included: Ascanio Sforza, Zeno, Caraffa, Pallavicini, Sciaffenati, and Domenico della Rovere. The same can be said of Carafa, whose core included: Orsini, Conti, della Porta, Riario, Medici, Sanseverino, Borgia, Piccolomini, and Ascanio Sforza—through all three scrutinies. The Portuguese Cardinal da Costa enjoyed support from Basso della Rovere, Giuliano della Rovere, Pallavicini, Gherardo, Cibo, Savelli, Sciaffenati, and Cibo. Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere (S. Pietro in Vincoli) regularly received the votes of: Fregoso, Colonna, Michiel, Costa and Zeno. At the same time, the cardinals did not seem to be narrowing the field of candidates. On the contrary, the number of cardinals receiving votes, and the total number of votes, kept increasing.

During the evening of August 10, and far into the night, the bargaining continued; if the election could not be won at the ballot, it could be won through the wallet. The promises and bribes of Rodrigo Borgia finally succeeded. Even the three holdouts, Carafa, Medici, and Piccolomini, finally gave in. Only two cardinals stubbornly refused to capitulate, della Rovere and da Costa. The Florentine Orator, Filippo Valori attributes Borgia's success to the indefatigable work of Cardinal Sforza (letter of August 12). Needless to say, Florence was not happy with the choice of Borgia.

At the eleventh hour next morning, Saturday, August 11, 1492, it was announced to the assembled crowd before St. Peter's Basilica that a pope had been elected. This must have come on the fourth scrutiny, on the morning of August 11, though probably only at the accessio. Alexander VI's first act was to name Cardinal Ascanio Sforza Vice-Chancellor [ left ]. Infessura (Diario, p.281) sarcastically remarks that, having become pope Borgia gave away all his property to the poor— to poor Cardinal Orsini he gave his palace and the citadels of Monticelli and Surano; he named poor Cardinal Ascanio (Sforza) Vice-Chancellor; he made poor Cardinal Colonna Abbot of Subiaco with all of its feudal dependencies; to poor Cardinal Sancti Angeli (da Costa) he gave the bishopric of Porto, its castle and all of its contents including the wine-cellar; the poor Cardinal of Parma (Schiaffinati) got the city of Nepi; Cardinal Ianuensis (Fregosi) got the title of S. Maria in Via Lata; Cardinal Savelli got Civita Castellana and the archpriesthood of Santa Maria Maggiore; others got cash, including Cardinal Gherardo, the Patriarch of Venice pro habenda voce ipsius. Only five cardinals got nothing. The Cardinals escorted Pope Alexander VI to the high altar of the Vatican Basilica for the second adoration. After Mass, the cardinals dispersed to their own palaces, except for Cardinal Sforza, who lunched with the Pope. Bernardino Luna of Pavia was named Papal Datary, on the recommendation of Cardinal Sforza. The incumbent Datary, Juan Lopez, who had also been Secretary of the College of Cardinals, was sent off to be Bishop of Perugia (December 29, 1492), and was later elevated to the rank of Cardinal (February 19, 1496).

At the eleventh hour next morning, Saturday, August 11, 1492, it was announced to the assembled crowd before St. Peter's Basilica that a pope had been elected. This must have come on the fourth scrutiny, on the morning of August 11, though probably only at the accessio. Alexander VI's first act was to name Cardinal Ascanio Sforza Vice-Chancellor [ left ]. Infessura (Diario, p.281) sarcastically remarks that, having become pope Borgia gave away all his property to the poor— to poor Cardinal Orsini he gave his palace and the citadels of Monticelli and Surano; he named poor Cardinal Ascanio (Sforza) Vice-Chancellor; he made poor Cardinal Colonna Abbot of Subiaco with all of its feudal dependencies; to poor Cardinal Sancti Angeli (da Costa) he gave the bishopric of Porto, its castle and all of its contents including the wine-cellar; the poor Cardinal of Parma (Schiaffinati) got the city of Nepi; Cardinal Ianuensis (Fregosi) got the title of S. Maria in Via Lata; Cardinal Savelli got Civita Castellana and the archpriesthood of Santa Maria Maggiore; others got cash, including Cardinal Gherardo, the Patriarch of Venice pro habenda voce ipsius. Only five cardinals got nothing. The Cardinals escorted Pope Alexander VI to the high altar of the Vatican Basilica for the second adoration. After Mass, the cardinals dispersed to their own palaces, except for Cardinal Sforza, who lunched with the Pope. Bernardino Luna of Pavia was named Papal Datary, on the recommendation of Cardinal Sforza. The incumbent Datary, Juan Lopez, who had also been Secretary of the College of Cardinals, was sent off to be Bishop of Perugia (December 29, 1492), and was later elevated to the rank of Cardinal (February 19, 1496).

An anonymous Florentine chronicler remarks, " Fu la sua publicatione adi XI ad hore X 1/2 et giunse a Firenze la nuova in spatio d' hore XII, la quale appena si crede, et per le sopradette ragioni et perche allo stato nostro presente quello cardinale amico non era." Alexander VI was no friend of Florence.

Stefano Infessura claims that during the Sede Vacante of 1492, some two hundred and twenty men were killed, at various times and in various places [Stefano Infessura, Diario, p. 282 ed. Tommasini]

Rodrigo Cardinal de Borja y Borja was crowned as Pope Alexander VI on Sunday, August 26 by Francesco Todeschini-Piccolomini, the future Pope Pius III (Burchard, 75-83 T). He took possession of the Lateran Basilica on the same day, collapsing with fatigue at the door of the Lateran. (Burchard, 83-90 T). On August 31, 1492, Pope Alexander held a Consistory, in which he elevated his nephew, Johannes Borja, Bishop of Monreale (1483-1503), to the cardinalate. He also made Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere Legate in Avignon; Cardinal Paolo Fregosi Legate in the Campagna; Cardinal Giovanni Battista Savelli Legate in the Duchy of Spoleto; Cardinal Giovanni Battista Orsini Legate in the Marches; and Cardinal Ascanio Sforza Legate in Bologna. He also moved Cardinal Giovanni Michaeli (Michiel) from Palestrina to Porto; and Cardinal Geronimo Basso della Rovere became Bishop of Palestrina

Bibliography

Achille Gennarelli (editor), Johannis Burchardi Argentinensis ... Diarium ... (Firenze 1854), 193-199. L. Thuasne (editor), Johannis Burchardi Argentinensis . . . Diarium sive Rerum Urbanum commentarii Volume I (Paris 1883) pp 567-580 (reports of Filippo Valori, the Florentine ambassador to Lorenzo il Magnifico; a report by Michele Ferno of Milan). Stefano Infessura, Diario della citta di Roma (a cura di Oreste Tommasini) (Roma 1890) 276-282. Onuphrio Panvinio, Epitome Pontificum Romanorum a S. Petro usque ad Paulum IIII. Gestorum (videlicet) electionisque singulorum & Conclavium compendiaria narratio (Venice: Jacob Strada 1557) 348-349. "Interpontificii historia ex Italico anonymi coaevi," in Daniel Papebroch Conatus chronico-historicus ad catalogum Romanorum Pontificum (Antwerp: Michael Knobbarus 1685) pp.140-142.

Cesare Baronius, Od. Reynaldi, et Jac. Laderchi, Annales Ecclesiastici (edited by Augustinus Theiner, Orat.) Tomus trecesimus (1454-1480) (Barri Ducis 1876) [Baronius-Theiner]. Lodovico Antonio Muratori, Annali d' Italia dal principio dell'era volgare sino all' anno MDCCXLIX. Tomo decimoterzo, dall' anno MCCCCX dell'era volgare fino all' anno MD. edizione seconda (Milano; Giambatista Pasquale, 1753).

Bartolommeo Platina, Historia B. Platinae de vitis Pontificum Romanorum...que ad Paulum II Venetum ... doctissimarumque annotationum Onuphrii Panvinii (Cologne: apud Maternum Cholinum 1568). Bartolommeo Platina, Historia B. Platinae de vitis pontificum Romanorum ...cui etiam nunc accessit supplementum... per Onuphrium [Panvinium]... et deinde per Antonium Cicarellam (Cologne: Cholini 1600). [Gregorio Leti], Conclavi de' pontefici romani (1667), 73-76; (Cologne: Lorenzo Martini 1691) I, 130-135 [highly inaccurate in its facts]. [Gregorio Leti], Histoire des conclaves 3rd edition (Cologne 1703) I, pp. 60-63.

Lorenzo Cardella, Memorie storiche de' cardinali della Santa Romana Ecclesia Tomo III (Roma: Pagliarini 1793). Gaetano Moroni Dizionario di erudizione storico-ecclesiastica 36 (Venezia 1846) 6. F. Petruccelli della Gattina, Histoire diplomatique des conclaves Volume I (Paris 1864) 341-354. Ludwig Pastor, The History of the Popes (edited R. K. Kerr) second edition Volume 5 (London: Kegan Paul 1902) 318-321; 375-390. Ferdinand Gregorovius, The History of Rome in the Middle Ages (translated from the fourth German edition by A. Hamilton) Volume 7 part 1 [Book XIII, Chapter 4] (London 1900) 320-327. A. Leonetti, Papa Alessandro VI Volume I (Bologna 1880) pp. 33-69. Joseph Schnitzer, "Zur Geschichte Alexanders VI.," Historisches Jahrbuch 21 (1900), 1-21. Ferdinando La Torre, Del Conclave di Alessandro VI, papa Borgia (Firenze: Olschki 1933) [an attempt to demonstrate that there was no simony at the Conclave of 1492, thereby saving the Papacy the embarassment of a Simoniacal Pope, Alexander VI. It is no more successful than Robert Bellarmine's exculpation of Julius II].

On Cardinal Riario: Angelo Poliziano, "La congiura de' Pazzi," Prose volgari inedite et poesie latine e greche edite e inedite (edited by Isidoro del Lungo) (Firenze 1867), p. 94. Niccolò Machiavelli, History of Florence Book VIII, chapter 1. G. Moroni, Dizionario di erudizione storico-ecclesiastica 57 (Venezia 1852) [though he gives no details about the conclave of 1492]. Charles Berton, Dictionnaire des cardinaux (1857) p. 1445. Erich Frantz, Sixtus IV und die Republik Florenz (Regensburg 1880) 197-230, especially 207 (highly favorable to Sixtus and the Riarios).

On Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia: M.-J. H. Ollivier, O.P., Le Pape Alexandre VI. Première partie: Le Cardinal de Llançol y Borgia (Paris: 1870).

Giovanni Battista Picotti, La Giovinezza di Leone X Milan 1927), 406-435; 445-460.. G. B. Picatti, "Nuovi Studi e documenti intorno a papa Alessandro VI," Rivista di storia della Chiesa in Italia V (1951), 243-247.