SEDE VACANTE 1513

February 21, 1513—March 11, 1513

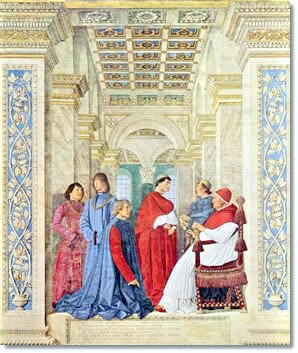

Platina is the kneeling figure,

Raffaele Riario is in blue, the future Julius II in the center.

and Pope Sixtus IV seated at the right.

No coins or medals were issued.

Raffaele Sansoni Galeotti Riario (May 3, 1461—July 9, 1521) was born at Savona, the son of Antonio Sansoni and of Pope Sixtus IV's sister Violentina. On December 10, 1477, while engaged in the study of law at the University of Pisa, he was created Cardinal Deacon of San Giorgio in Velabro by his uncle Pope Sixtus (1471-1484). He was 17. He was suspected of having had some connection with the Pazzi conspiracy, April 1478, through his uncle Count Girolamo Riario and Francesco Salviati, Archbishop of Pisa. Although he was arrested and imprisoned, his uncle the Pope had him freed and brought to Rome, where he was officially rehabilitated in consistory. He was named Chancellor of the Church [Cardella III, 210; accoreding to Moroni 57, 171, he was named Vice-Chancellor], and in 1483 he became Camerlengo of the Holy Roman Church, a post he held until his death in 1521. He was loaded with benefices by Sixtus IV and Innocent VIII (1484-1492), including the administration and income of sixteen rich bishoprics (including eventually Tréguier in France (1480-1483), Pisa (as Apostolic Administrator, 1479-1499), Salamanca (as Apostolic Administrator, 1482-1483), Osma (as Apostolic Administrator, 1483-1493), Cuença (as Apostolic Administrator, 1479-1482), Viterbo (as Apostolic Administrator, 1498-1506), and Savona (as Apostolic Administrator, 1511-1516); he was also Abbot of Monte Cassino and of Cava.

Under Alexander VI, however, he was in disfavor. The greed for power and property on the part of the Borgia family made the Riarios a major target. Alexander's son Cesare coveted the holdings of the Riario family, and seized the city of Forlì and also Imola. Riario fled to France and took up his bishopric of Tréguier. On his return in September of 1503 he was appointed Bishop of Albano (in November, 1503) and was consecrated bishop on April 9, 1504 by Pope Julius II personally (another nephew of Sixtus IV). In 1507 he was promoted to the bishopric of Sabina, and on July 7, 1508, became Apostolic Administrator of Arezzo. Julius II made him Cardinal Bishop of Ostia, Porto, and Velletri on September 22, 1508. He participated in five conclaves, including the conclaves of 1484, 1492, 1503 that elected Pius III and the one that elected Julius II, and that of 1513.

In 1517, he was involved in the conspiracy of Cardinal Alfonso Petrucci against the life of Pope Leo X (also involving Cardinals Soderini and Sauli) and was arrested (May 29) and incarcerated in the Castel S. Angelo (De Grassis, p. 48). Trials were held. The ambassadors of England, France and Spain interceded. The College of Cardinals intervened on his behalf when it appeared that Riario might be stripped of all of his benefices, degraded from the cardinalate, and condemned to death. On July 16, Cardinal Petrucci was executed in the Castel S. Angelo. On July 24, Riario was released from confinement and brought to the Vatican; after he swore an oath, he was admitted to the presence of the Pope (De Grassis, p. 57; Pastor, Geschichte, 691-693). After he confessed to the Pope in a lengthy speech and begged pardon—which the Pope was pleased to grant, with a huge fine, whose value changed repeatedly, and the confiscation of his palace at S. Lorenzo in Damaso (the Cancelleria)—pardon was granted. He was restored to the bishopric of Ostia at Christmas, 1518, and his fine was cancelled. He died in 'retirement' in Naples [See F. Cancellieri, Efemeridi letterarie di Roma (February 1822) 3-12].

Paris de Grassis, Papal Master of Ceremonies, records his death (p. 86):

Die nona julii mortuus est cardinalis Sancti Georgii, Raphael Riarius Savonensis, decanus colegii et episcopus ostiensis, qui cum esset aetatis suae anno decimonono creatus est a Sixto cardinalis, demum in vicesimo secundo camerarius in quo mansit annos viginti novem, et sic anno sexagesimoprimo vel circa obiit Neapoli. . . .

Cardinal Riario was also Dean of the College of Cardinals at the conclave of 1513, his fourth conclave.

The Governor of the Conclave was the Bishop of Treviso, Bernardo Rossi [I diarii di Marino Sanuto 16, column 11, and 14]

The Masters of Ceremonies were Paris de Grassis, Baldassare di Niccolò, and Ippolito Morbiolo, who was De Grassis' Auditor [and his nephew; Hippolytus Mostiolus, as he is called in Gattico I, p. 313]. They had two additional assistants inside the Conclave. Lodovico de Branca kept a diary of the reign of Leo X, including the Conclave that elected him; a copy in the hand of Paris de Grassis survives in the Vatican Library (Vat. Lat. 5636) [V. Forcella, Catalogo dei manoscritti relativi alla storia di Roma I (Roma 1879), p. 63-64, no. 211].

The Governor of Rome was Msgr. Lorenzo Fieschi, Bishop of Mondovi, who was also Vice-Chamberlain (1512-1519) [Mansi 32, columns 677, 708, 728, 744].

The Senator of Rome was Giulio Scorzati [Concilium Sanctum Lateranense novissimum (Romae 1521), lix]. The Conservatores Urbis were led by Hieronymus Benzon [Francesco Vitale, Storia diplomatica de' senatori di Roma II (Roma 1791), pp. 494-497; Luigi Olivieri, Il senato romano I (Roma 1886), p. 283-285].

The Imperial Ambassador was Alberto da Carpi. The Ambassador of King Ferdinand of Aragon and Castile was Hieronymous Vich. The Ambassador of the Serene Republic of Venice was Francesco Foscari. The Ambassadors of Florence were Jacobus Salviati and Matteo Strozzi. The Ambassador of Lucca was Bonus de Francischis. The Ambassador of Savoy was Msgr. Ercole d'Azeglio, Bishop of Aosta (1511-1515).

Death of Pope Julius

It was reported in Venice on February 10, with additional details on the 12th and 15th, that Pope Julius was seriously ill with the double tertian fever (malaria) [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 15, cols. 559 and 554]:

In la prima, come il Papa havea di mal assai; li era scoperto la febre freda e calda, qual veniva a ore 22, sichè è da dubitar assai, et zà se principiava le pratiche al papato. El Papa non obedisse li medici, è di soa voja; tamen è di forte natura. Ha febre dopia terzana; ha fato renovar uno monitorio et ordination che non si elevi Papa per symonia, e benchè el sia amalato, atende a la impresa di Ferara.

A letter of the Venetian Orator in Rome, Francesco Foscari, dated February 13, reported that, in the judgment of the papal doctors, the Pope could not last until the full moon, which was on Saturday, February 19. He also noted that the Orsini and the Colonna were advancing on Rome. There was politicking going on about the election of a new pope, and the leading papabili were Riario, Fieschi, Tommaso Bakócz, and the Venetian Grimani. The remark of Frederick Corvo is perhaps relevant, however, "The Orators of the Powers compile their state-dispatches from what they have picked up when hanging about the doors of palaces, or from the observations of bribed flunkeys."

The Florentine Ambassador in France, Roberto Acciaioli, reported on February 14, that King Louis XII was pressing the Cardinals to start their journey for Rome. He wanted a pope who would arrange a peace with France, and he wanted the schismatic cardinals admitted to Conclave. There was a great deal of resistance. Louis also wrote to the College of Cardinals not to rush into an election, but to wait for foreigners to arrive [Petruccelli I, 486].

On February 16, the Fifth Session of the Lateran Council took place, though without the presence of the dying Julius II. Cardinal Riario presided in his place. The bull of Julius II against simony (de simoniaca electione of January 14, 1505), was read out, and ratified by the Council [Baronius-Theiner 31, sub anno 1517 no. 2-6, pp. 1-3; Mansi, Sacrorum Conciliorum nova et amplissima collectio 32, col. 656]. The list of those in attendance at the Fifth Session is given by Mansi (columns 762-766); it included nineteen cardinals, among them all but one of the Cardinal Bishops (Philip of Luxembourg). Absent from the bench of Cardinal Priests were: Remolins, Adriano di Castello, Sisto della Rovere, and Carretto. Only Medici was missing from the bench of Cardinal Deacons. The Council was prorogued until April 11 [Marino Sanuto 16, 15].

A letter to Venice from Florence, sent on February 19 [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 15, 572], provides interesting gossip:

... et poi vi era uno secretario del cardinal di Ragona [Luigi d'Aragona], e razonando zercha la malatia dil Papa con dito secretario, li disse s' il Papa moriva, l'andava da San Zorzi [Raffaele Sansoni Riario], Flisco [Niccolò Fieschi] et Istrigonia [Tamás Bakócz]; et che non potendo esser San Zorzi, farà Hongaro, per esser vechio et ha assa' danari; e che s' il Medici non fosse si zovene, non saria altri che lui; et che 'l stà a soa signoria a far Papa chi 'l vorà, e che l'à una gran parte di cardinali. Li disse l' Hongaro havia 72 anni. Scrive, el cardinal vol non si parti de li fin non si veda l' exito dil Papa, perchè se 'l fosse morto, le strade sariano rote. Eri sera si ebe letere di Roma di 16, che 'l Papa era miorato. Scrive, starà a veder e se governarà per zornata....

On the morning of February 19 the Venetian Ambassador reported that the Pope had received Holy Communion from the hand of the Cardinal of S. Giorgio, Cardinal Riario, and, at the direction of the Master of Ceremonies, Paris de Grassis, the plenary indulgence was conferred on the dying pope. Then Pope Julius ordered the Cardinals to assemble and he made a speech to them in Latin, exhorting them, after his death, to elect a pope rite et recte. The election was to be carried out by the Cardinals alone, not by the Lateran Council (looking back, no doubt, to the Election of 1417 at Constance, which had produced a century of struggle over the Conciliar Theory). The Cardinals who had been deposed were not to be admitted. As a private person, however, Julius forgave them and blessed them. He also gave instructions to the Castellan of Castel S. Angelo not to turn over the papal treasury or jewels or the Castel itself to anyone except the next pope. [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 15, 560; similarly in a letter of Hieronymo di Grassi to Leonardo di Grassi, Sanuto 15, 565]. Pope Julius II died on February 21, 1513.

On the 20th the Cardinals held a Congregation, and ordered the Duke of Urbino, Pope Julius' nephew, to come to Rome as Captain of the Church with his cavalry and infantry, for whom they authorized the expenditure of 9,000 ducats. They authorized the Captain of the Swiss Guards, who had 180 soldiers, to increase his force to 300 [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 15, 561].

Pope Julius II (Della Rovere) died of a fever on Monday, February 21, 1513 [Concilium Sanctum Lateranense novissimum (Rome 1521), lxx; Pastor, Volume 6, pp. 433-436]. He was 68. Paris de Grassis put the time of death at the tenth hour of the night between February 20 and February 21. The Spanish Ambassador, the Orsini, and the Colonna promised the College of Cardinals that the election would be peaceful [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 16, 14]. On February 22, the College of Cardinals wrote a letter to King Louis XII of France, notifying him of the death of the Pope [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 16, 15].

On February 22, the body of the pope lay in state in the Vatican Palace. There was a Congregation of the Cardinals at the palazzo of Cardinal Riario, where arrangements for the Pope's funeral and the Novendiales were made. Letters were dispatched by the College of Cardinals to the various powers, requesting them to honor the need to have a free election; the letter to Venice is preserved in Senator Marino Sanuto's diaries [Volume 15, column 582]. On the same day the Orsini and the Colonna factions entered Rome. After the Congregation concluded its business, the body of the pope was transferred to the Vatican Basilica. That night, an hour after sunset, the body was buried in the Chapel of Pope Sixtus [letter of Hieronymo Crasso to Leonardo Crasso, Rome, February 24, 1513, in Diarii di Marino Sanuto 16, 14].

On February 23, there was a brief Congregation of the Cardinals, followed by .a requiem mass in St. Peter's sung by Cardinal Marco Vigerio della Rovere. The funeral oration was preached by Tommaso Fedro Inghirami, Custodian of the Vatican Basilica and Secretary of the Sacred College of Cardinals. This was in accordance with the wishes of Julius II, expressed while he was still alive [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 16, column 13; Novaes, Introduzione I, pp. 255-256]. There was a dispute between the Conservatori of Rome and the Ambassadors of Florence for precedence in the chapel. The Venetian ambassador believed that Cardinals Cornero and Grimani met, made peace, and agreed that Cornero would support Grimani in the Conclave [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 16, 16]. It was on the morning of the 23rd that the news reached Venice by way of the Duke of Ferrara that the Pope had died on the 21st. The Ambassador to Venice of Hungary, Filippo More, reported in person the same news later in the morning. He also had a request of the Signoria of Venice [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 15, 557]:

... pregava la Signoria volesse scriver a li nostri cardinali, non potendo far per loro, dovesseno ajutar el reverendissimo Istrigonia cardinal hongaro, qual è sempre stato amico di questo Stado, e s'il fusse, saria bon pontefice. Il Principe li disse come questo Stado aria grandissimo a piacer fusse soa reverendissima signoria, perchè reputavemo venitian proprio, et li nostri cardinali sapeva la volontà nostra.

The effort of the Venetians was, of course, being directed to the election of their own Cardinal Grimani [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 15, 554].

On Thursday, February 24, the Mass was sung by the Cardinal of Nantes, Robert Guibé. At the palazzo of Cardinal Grimani there was a private meeting with Cardinal Fieschi and Cardinal Luigi d'Aragona. It was a question of benefices, in fact, and letters which Pope Julius had given to the three cardinals—as Ser Hieronymo discovered the next day. Fabrizio Colonna, Giovanni Giordano Orsini and Julio Orsini met with Cardinal Raffaele Riario, the Camerlengo—ad quid nescio, remarks the Venetian [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 16, 15].

By February 25, there were twenty cardinals in Rome. Five more were expected from one hour to the next. Medici was already there on the 26th, by the positive report of Bishop Nicolao Lippomano of Bergamo. Cardinal Cornèr was saying that Grimani would be pope. He also reports that on February 28, Bibbiena was noticed to be out campaigning for Cardinal de' Medici. He also reports gossip that if you ask Cornèr, then Grimani will be pope; if it's a question of money, the chances are that Bakócz will be pope, and then Riario. In a letter of March 2, he claims that Riario was against Fieschi. [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 16, 19].

On March 2, there were 23 cardinals in Rome, according to the Venetian Ambassador. This is also the report of Bishop Lippomano [Marino Sanuto 16, columns 18 and 19]. Cardinal Adriano di Castello had not yet arrived from his Legateship in Germany.

The Cardinals

At the time of Julius II's death there were thirty-one cardinals. Pastor (Volume 7, 15-16) lists them: of the Italians, Pietro Accolti (Bishop of Ancona), Adriano Castellesi, Marco Cornaro, Alessandro Farnese, Niccolò Fieschi, Sigismondo Gonzaga (son of the Marquis of Mantua), Achille de Grassis (Bologna), Domenico Grimani, Luigi d' Aragona, Giovanni Medici, Antonio Ciocci del Monte Sansovino (Archbishop of Liponto), Alfonso Petrucci (Siena), Raffaele Riario (nephew of Sixtus IV), Leonardo Grosso della Rovere (nephew of Sixtus IV), Bandinello Sauli (Genoa), Francesco Soderini, and Marco Vigerio (grand-nephew of Sixtus IV, bishop of Senigaglia); there were two Spaniards, Francesco Remolino and Jacopo Serra; the Frenchman Robert Challand (bishop of Rennes); the German-Swiss Matthias Schinner (Bishop of Sitten); the Hungarian Primate Tommaso Bakócz (who was also Latin Patriarch of Constantinople); and the English Cardinal Christopher Bainbridge (York). The cardinals who had been deposed by Pope Julius because of their participation in the Council of Pisa were excluded, Bernardino Carvajal, Guillaume Briçonnet, Francesco Borgia, René de Priè (Bishop of Bayonne), and Federigo di Sanseverino. The Conclave took place in the Vatican Palace.

Guilelmus van Gulik & Conradus Eubel Hierarchia catholica III (Monasterii 1923), p. 13, n. 2, provides a list of the twenty-five cardinals who entered Conclave on March 4, 1513. The date and number of cardinals is given by Paris de Grassis in his Diarium Ceremoniale [p. 1 Armellini]. Thirty-one cells were built in the conclave area, respecting the fact that there were thirty-one living cardinals, not counting the Schismatics [Paris de Grassis Diarium, in Gattico I, p. 311]. Armellini provides a list of the Cardinals and their conclavists, as well as the names of the absent cardinals (at pp. 91-94), drawn from a ms. collection of conclave materials in the Vatican Archives (Archivium Vaticanum, Arm. XII, 122). A list of the cardinals who were present at the Fifth Session of the V Lateran Council on February 16, 1513, is given in J. D. Mansi, Sacrorum Concilium nova et amplissima collectio 32, columns 762-763; it includes five cardinal-bishops, nine cardinal-priests, and five cardinal-deacons.

Seventeen votes were needed to elect.

- Raffaele Sansoni Riario (aged 51) [Savona], son of Antonio Sansoni and Violante Riario, sister of Cardinal Pietro Riario. Bishop of Ostia e Velletri (1508-1521), Dean of the Sacred College of Cardinals. Apostolic Administrator of Savona (1511-1516) "San Giorgio"

- Domenico Grimani (aged 52) [Venetus], Bishop of Porto e Santa Rufina (1511-1523), previously Bishop of Frascati (1509-1511), and before that Bishop of Albano (1508-1509), and Cardinal Priest of S. Marco (1503-1523). In 1505 he became Protector of the Basilian Monks. On March 19, eight days after the election of Leo X, he was granted an annual pension of 2000 ducats [Eubel III, p. 5 n. 4].

- Jaime Serra i Cau (aged 85 ?) [Hispanus], Bishop of Albano (1511-1517), previously Cardinal Priest of S. Clemente (1502-1511). Apostolic Administrator of Linkoping, Sweden (1501-1513). Apostolic Administrator of Elne (France) (1506-1513). Died March 15, 1517. "Arborense" On March 19, 1513, eight days after the election of Leo X, he was granted an annual pension of 2000 ducats [Eubel III, p. 7 n. 2].

- Marco Vigerio della Rovere, OFMConv. (aged 66) [Savona], Bishop of Palestrina (1511-1516) [Ughelli-Colet Italia sacra I, 219], previously Cardinal Priest of S. Maria in Trastevere (1505-1511). Bishop of Senigaglia (1476-1513) [Ughelli-Colet Italia sacra 2, 876-877]. Master of Theology at the Sapienza (Rome). Previously Regent-Master in Theology at Padua. Nephew of Marco Vigerio, Bishop of Noli. Grand-nephew of Sixtus IV. [Ughelli-Colet 2, 876; 4, 1007]. He wrote an Apologia against the 'Council of Pisa' "Senogalliensis"

- Francesco Soderini (aged 59) [Florentinus], Bishop of Sabina (1511-1513), previously Cardinal Priest of SS. XII Apostoli (1508-1511) and S. Susanna (1503-1508). Apostolic Administrator of Saintes (1507-1514). "Volaterranus" He received special consideration at the Conclave since he was "infirmus" [Paris de Grassis, in Gattico I, 312]. On March 19, eight days after the election of Leo X, he was granted an annual pension of 2000 ducats [Eubel III, p. 8 n.5].

- Tamás Bakócz (aged 70) [Hungarian], Archbishop of Strigonia (Esztergom) (1497-1521), and titular Patriarch of Constantinople (1507-1521) Cardinal Priest of SS. Silvestro e Martino (1500-1521). Former Chancellor of the King of Hungary. He was present in Rome at all five sessions of the Fifth Lateran Council, held under Julius II, from May 12, 1512 to February 16, 1513. On July 15, 1513, he was named by Pope Leo X Legatus a latere to Hungary, Bohemia and Poland; on November 9, 1513, he departed from Rome for Hungary, by way of Ancona [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 17, 318, 333, 358, 424]. In 1518 his legatine commission was extended [Eubel III, p. 7 col. 2, n. 1]. Died June 11, 1521.

- Francisco de Remolins (aged 50) [Hispanus], Cardinal Priest of S. Marcello (1511-1517) and Cardinal Priest of SS. Giovanni e Paolo (1503-1511, and in commendam 1511-1517) . Bishop of Fermo (1503-1518), quam ille ecclesiam fere semper absens administravit [Ughelli-Colet, Italia sacra 2, 719]. Bishop of Terni (1504-1518). Apostolic Administrator of Palermo (1512-1518) Archpriest of the Liberian Basilica (1511-1518). Died February 5,1518 [Eubel III, 8]. Eight days after the election of Leo X, the new Pope granted Cardinal Remolino 135 ducats from the income of the Benedictine Monastery of S. Stefano in Bologna; on May 11, the Pope named him Prior of S. Sepolcro de Calatajubio in the diocese of Tarazona [Eubel III, p. 8, n. 1].

- Niccolò Fieschi (aged 56) [Januensis], Cardinal Priest of S. Prisca (1506-1518), previously Cardinal Deacon of S. Lucia in Septisolio (1503-1506). Apostolic Administrator of Agde (1504-1524), and of Embrun (1510-1518). Died June 15, 1524.

- Adriano di Castello (aged 54) [Corneto, Tuscany], Cardinal Priest of S. Crisogono (1503-1518). Secretary of Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia, Adriano was the Pope's secretary of Briefs at the time of his elevation to the cardinalate in 1503, and continued to function as such for some weeks thereafter [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 4, 698, 768, 813; 5, 53; Dispacci di Antonio Giustinian II, 3 (May 2, 1503); 7 (May 6, 1503), 29 (May 31, 1503), 44 (June 22, 1503)]. Early in his career he was sent as Papal nuncio to Scotland, and collector of the Peter's Pence in England, 1488. Notary of the Apostolic Camera [Burchard Diarium I, 352 (April 24, 1489)]. Cleric of the Apostolic Camera [Burchard, Diarium II, p. 334 Thuasne (July 31, 1496), p. 349; p. 386 (June 4, 1497)]. He was made a protonotary apostolic on October 14, 1497 [Burchard Diarium II, 410]. On June 4, 1498, he departed Rome as member of a legation to the King of France [Burchard Diarium II, 474]. He participated (as protonotarius et secretarius) in the ceremonies of Christmas Day, 1499, for the beginning of the Jubilee of 1500 [Burchard Diarium II, 502, 602, and 582-602]. Bishop of Hereford, England (Provided February 14, 1502; consecrated May 9, 1502; translated to Bath and Wells, August 2, 1504) [Le Neve, Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae I, 143 and 466-467; Cassan, Lives of the Bishops of Bath and Wells, 331-346]. He had written a book on hunting, which he dedicated to Cardinal Ascanio Maria Sforza. In June, 1503, shortly after his elevation to the Cardinalate, he was in discussions with the Venetian Ambassador Giustiniani to bring about an alliance between Alexander VI and Venice [Dispacci di Antonio Giustinian II, 37 (June 10, 1503)]. Bishop of Hereford (consecrated May 9, 1502). Translated to Bath and Wells, by papal bull, on August 2, 1504. He was enthroned by proxy in Wells Cathedral, on October 20, Polydore Vergil acting as his proxy. He built the palace in the Borgo, now known as the Palazzo Torlonia, on the Via della Conciliazione, some time in the reign of Alexander VI. The facade carried a dedicatory inscription to King Henry VII. This palace came into the possession of the Kings of England, and was the English Embassy in Rome [Cassan, Lives of the Bishops of Bath and Wells, 332; Brady, "The English Palace in Rome," Anglo-Roman Papers, 13]. As a very rich cardinal he feared the greed of Alexander VI and Cesare Borgia; he was also a great enemy of Julius II, and stayed in his legation in Germany during his reign [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 15, 488]. In mid-September, 1512, it was reported from Verona that he had conversations at Rovere(to), lasting several days, with Matthäus Lang of Gurk, who was going to Rome [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 15, 107] . Nonetheless, it was reported at Venice on February 23 that he was coming from Germany to participate in the Conclave, and that he was travelling incognito [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 15, columns 559-560]. On February 27, he was at Rovigo and heading for Ferrara [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 15, 571]. He was deprived of his cardinalate and benefices in July, 1518 [Le Neve, Fasti I, pp. 143, 466-467]

- Robert Guibé (Chailland) (aged 53) [Brittany], nephew of Bishop Raphael (Radulphus Rolland) of Tréguier, Cardinal Priest of S. Anastasia (1505-1513). Administrator of Tréguier (1483), while still a minor. He was a member of an embassy of the Duke of Brittany to the Pope in February of 1485. He was in Rome on another embassy in 1499. Bishop of Rennes (1502-1507). Archbishop of Nantes (1507-1511), through a procurator [Eubel III, p. 252]. Administrator of Albi (1510-1513) and Vannes (1511-1513). Ambassador of King Louis XII of France to the Pope, 1511, but his support of the Pope caused him to lose his French benifices. Died in Rome on November 9, 1513. [Gallia christiana 14, 760 and 832-833, 1131] "Nannetensis"

- Sisto de Franciottis della Rovere (aged 39) [Savona], Cardinal Priest of S. Pietro in Vincoli (1507-1517). Bishop of Padua (1507-1517), Administrator of Benevento (1508-1514), Lucca (1507-1517), and Saluzzo (1512-1516). Grand Prior of Rome of the Order of Hospitallers (1509-1512) [J. Delaville de Roulx, Mélanges G. B. Rossi (1892) p. 268]. Vice-Chancellor S.R.E. (1507-1517). Nephew of Julius II. (died 1517). He received special consideration at the Conclave since he was unable to walk [Paris de Grassis, in Gattico I, 312].

- Leonardo Grosso della Rovere (aged 48) [Savona], Cardinal Priest of S. Susanna (1508-1517). Bishop of Agen (1487-1519). Major Penitentiary (1511-1520). Nephew of Julius II (died 1520).

- Carlo Domenico del Carretto (aged 58), Marquis de Finarii [Liguria], Cardinal Priest of S. Niccola fra le Immagini (1507-1513). Previously Cardinal Deacon of S. Vito (1505-1507). Archbishop of Tours (1509-1514). Archbishop of Reims (1507-1509). Titular Archbishop of Thebes (1492 -1507). Apostolic Administrator of Angers (1491-1492). Bishop of Cosenza (1489-1491). He was created cardinal in 1505, at the request of Louis XII, and worked continually to reconcile Julius II and King Louis XII. He secretly favored the schismatic Council of Pisa [Gallia christiana 9, column 145]. He died on August 15, 1514. "Finarius"

- Christopher Bainbridge (aged 48) [England], nephew of Thomas Langton, Bishop of Winchester (1493-1501). Cardinal Priest of S. Prassede (1511-1514). Archbishop of York (1508-1514). He had been a constant supporter of Henry VII against Richard III; Almoner to Henry VII. Ambassador of Henry VII to Pope Alexander VI.

Bishop of Durham (1507-1508) [Le Neve, Fasti III, p..298]. Dean of Windsor (1505-1507) [Le Neve, Fasti III, p. 373]. Dean of York (December 1503–December 1507) [Le Neve, Fasti III, p.125].. Master of the Rolls (1504-1507). Prebend of Stensall, in the Cathedral of York (1503-1504) [Le Neve, Fasti III, p.216]. Prebend of Bath. Archdeacon of Surrey (1501). Treasurer of St. Paul's Cathedral (1497). Prebend of North Kelsey in the Cathedral of Lincoln (1496-1500). Provost of Queens College, Oxford (attested in 1495) [Le Neve, Fasti III, p. 552]. Prebend of South Grantham, then Chardstock, in the Cathedral of Salisbury (1485). Doctor legum (Oxford). [See Dictionary of National Biography I (London 1908), 905] Died by poison in 1514; he was buried in the English College, Rome. One of his conclavists in 1513 was Richard Pace [Armellini, p. 93], who was also one of the executors of the Cardinal's Will [DNB I, p. 905]; he was in Rome from 1509-Spring, 1515 [DNB 43, p. 22]. - Antonio Maria Ciocchi del Monte (aged 51) [Monte S. Savino, diocese of Arezzo, Tuscany], Cardinal Priest of S. Vitale (1511-1514). Auditor of the Sacred Roman Rota (1493). Auditor of the Apostolica Camera (1504). Bishop-elect of Citta di Castello (1503-1506). Administrator of Pavia (1511-1521).

- Pietro Accolti (aged 57) [Florentinus], Cardinal Priest of S. Eusebio (1511-1523). Bishop of Ancona (1505-1514). Administrator of Maillezais (1511-1518). Vicar General of Rome (1510-1532). Auditor of the Rota. Secretary of Julius II. Professor of law at Pisa and at Bologna.

- Achille Grassi (aged 57) [Bononiensis], Cardinal Priest of S. Sisto (1511-1517). Bishop of Citta di Castello (1506-1516). Bishop of Bologna (1511-1518). Died November 2, 1523.

- Matthäus Schinner [Muhlbach, Switzerland], Cardinal Priest of S. Pudenziana (1511-1522). Bishop of Sion (Sitten, Sedunensis) (1499-1522) [Eubel III, p, 295]. Administrator of Novara (1512-1522). Legate in Germany and Lombardy, serenissimae Ligae gubernator [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 15, 256 (October 20, 1512)].

- Bandinello Sauli (aged 18) [Januensis], Cardinal Priest of S. Sabina (1511-1516). Bishop (!) of Gerace (1509-1517). He was involved in the Petrucci conspiracy against the life of Leo X. Died March 29, 1518, at the age of 24.

- Giovanni de' Medici (aged 37) [Florentinus], Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Domnica (1492-1513). Apostolic Administrator of Amalfi (1510-1513) Elected Pope Leo X (1513-1521). Prior Diaconorum Cardinalium [Paris de Grassis, Diarium, p. 1 ed.Armellini].

The Venetian Ambassador in Rome, Francesco Foscari, says that Cardinal de' Medici left Florence on the 26th [Marino Sanuto 16, 19], and in a letter of the Bishop of Bergamo, dated February 25, it is stated that Medici was expected in Rome on the next day, that is, on the 26th [Marino Sanuto 16, col. 13]. The Florentine diarist Luca Landucci [Diario fiorentino, p. 335 ed. del Badia], says that Cardinal de' Medici left Florence on February 22 con grande prestezza, which would accord with the Bishop's expectation of his arrival on the 26th. He was certainly in Rome by the 28th, according to the Florentine Ambassadors, Strozzi and Jacobus Salviati, who remark that his old complaint, a fistula, had returned [Petruccelli I, 486]. According to the Venetian Ambassador, Francesco Foscari, he was carried into the Conclave at the opening. [Marino Sanuto l6, 37]. One of his conclavists was Bernardo Dovizi da Bibbiena, who was named cardinal on September 23, 1513 [Gulik-Eubel III, p. 14; Bandini, Il Bibbiena, pp. 13-15]; Medici had extra conclavists because he was ill [Paris de Grassis Diarium in Gattico I, p. 312]. - Alessandro Farnese (aged 45), Cardinal Deacon of Ss. Cosma e Damiano (1493-1513) and Cardinal Deacon of S. Eustachio. (1503-1519). Archpriest of the Lateran Basilica (1508-1534). Administrator of Montefiascone (1501-1519). Bishop of Parma (1509-1519). Pope Paul III (1534-1549). On March 19, eight days after the election of Leo X, he was granted an annual pension of 2000 ducats [Eubel III, p. 5 n. 2].

- Luigi d'Aragona (aged 38), Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Cosmedin (1496-1519) and of S. Maria in Aquiro in commendam (1508-1517). Administrator of Aversa (1501-1515), and of Capaccio (1503-1514), and of Leon (1511-1516). On March 19, eight days after the election of Leo X, he was granted an annual pension of 2000 ducats [Eubel III, p. 6 n.1].

- Marco Cornaro [de Corneliis] (aged 30), Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Porticu (1500-1513). Apostolic Administrator of Verona (1503-1524). One of the supporters of Giovanni de' Medici [Marino Sanuto 6, 39, a letter of Vetor Lipomano, written in Rome on March 11 at the third hour of the night]. On March 19, eight days after the election of Leo X, he was granted two benefices, and on August 28 an annual pension of 100 gold ducats [Eubel III, p. 7 column 2 n. 3].

- Sigismondo Gonzaga (aged 43), brother of the Marquis of Mantua. Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria Nuova (1506-1525). His conclavist was Francesco Armellini, even though he was a Cleric of the Camera, a fact which caused much grumbling [Paris de Grassis, in Gattico I, 312-313]; Armellini was made a cardinal in 1517.

- Alfonso Petrucci (aged 21) [Senensis], said to have been Cardinal Priest of the Deaconry of S. Teodoro (1511-1517). In the list of Cardinals who attended the Fifth Session of the Lateran Council on February 16, 1513, however, he is listed as a Cardinal Deacon, not a cardinal priest (Mansi, 763). Likewise at Sessio IV (Mansi, 743), Sessio II (Mansi, 707); in a list of subscriptions (Mansi, 691) to Julius II's bull of August 15, 1511; and in Sessio I (Mansi, 677). He is still listed as a Cardinal Deacon under Leo X at Sessio VII (Mansi, 806). This is not a recent scholarly "correction". The Acta of the V Lateran Council, published in 1520 (p. lxxxv), list him as a Cardinal Deacon. [Gulik-Eubel III, p. 12 no 26, and p. 76]. Both G-Catholic and Salvador Miranda (who both make him a cardinal priest) are contradicted by the sources and the authorities. Bishop of Massa Marittima (1511 until he was deprived in 1517). He was executed in the Castel S. Angelo on July 16, 1517, at the age of 26, for attempted murder of Pope Leo X. At the Conclave of 1513 he was a partisan of Giovanni de' Medici.

- Ippolito I d'Este (aged 33), third child of Duke Ercole d'Este of Ferrara and Eleonora d' Aragona. At the age of three, he was made Abbot commendatory of Casalnovo. At the age of six he was tonsured and named Abbot commendatory of S. Maria di Pomposa. Cardinal Deacon of S. Lucia in Silice (1493-1520) at the age of 13. Apostolic Administrator of Milan (1497-1519) , and of Eger (1497-1520) at the age of 17. Archpriest of the Vatican Basilica (1501-1520). Died September 3, 1520.

- Philippe de Luxembourg (aged 67), Cardinal Bishop of Frascati (1511-1519) Died June 2, 1519.

- Amanieu d'Albret (aged 34), Cardinal Deacon of S. Nicola in Carcere (1500-1520). Apostolic Administrator of S. Bertrand-de-Comminges (1499-1514), and of Lescar (1507-1515).

- François Guillaume de Castelnau de Clermont-Ludève (aged 33), Cardinal Priest of S. Stefano al Monte Celio (1509-1523), previously Cardinal Deacon of S. Adriano al Foro (1503-1509). Archbishop of Auch (Auxitanensis) (1507-1538). Legate in Avignon 1507-1508. Administrator of Saint-Pons-de-Thomières (1511-1514).

- Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros, OFM.Obs. (aged 76), Cardinal Priest of S. Balbina Archbishop of Toledo (1495-1517) (died 1517)

- Matthäus Lang von Wellenburg (aged 44) [Augsburg, Bavaria], Cardinal Deacon of S. Angelo in Pescheria (since November 19, 1512, according to Gulik-Eubel, Hierarchia catholica III, p. 13—the only cardinal created on that day; but the treaty between the Pope and the Emperor was signed on the evening of November 19, 1512, at the Papal Palace by Matthias, Cardinal of Gurk: Bergenroth, p. 83. The date, then, is only a terminus ante quem, and there likely was no Consistory on that day to raise him to the Cardinalate; the Diaries of Marino Sanuto [15, 337] report that the Pope had made him a cardinal on the 15th). A letter from the Venetian Orator in Rome dated November 24, 1512, reported that the Pope had made Matheo Lanch a cardinal [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 15, 361]: è sta fatò per il Papa et pronontiato cardinal il reverendo domino Matheo Lanch episcopo curzense, et datoli il titolo di Sancti Angeli, qual havia il Cardinal San Severino ch' è stà privato dil capello; e che dito Curzense dovea andar col Papa a Ostia e star do zorni, poi dize partirà sabado a di 27, nè si vol ritrovar a l' intrar in Concilio si farà a di 3. Bishop of Gurk (1505-1522). Bishop of Cartagena (1510-1540). He had been secretary of Berthold von Henneberg, Archbishop-Elector of Mainz. He then was secretary of Emperor Maximilian I.

He was the principal negotiator of the treaty of 1512 between the Emperor and the Pope, and between the Emperor and the English and Spanish. Gurk was working for the Emperor, not the Pope [Bergenroth, Calendar of Letters, Dispatches and State Papers, relating to the Negotiations between England and Spain II (London 1866), pp. 79-91, 107; Diarii di Marino Sanuto 15, 326, 339-340]. He was in Rome on November 23, 1512, when he wrote to Archduchess Margaret [Bergenroth, p. 79 n.]. At the Third Session of the V Lateran Council, on December 3, 1512, he acted as Imperial Ambassador along with Hieronymus Vich and Alberto de Carpi [Mansi 32, columns 731-733], though, curiously, he is not listed as a cardinal, but as Locumtenens Maximiliani. Reverendus et Illustris Dominus Mattheus Episcopus Gurcensis, serenissimi domini Maximiliani electi imperatoris. Cardinals are listed as Reverendissimus Dominus. He presented the Imperial Mandate, as well as a repudiation of the Pisan council of 1511. Lang was not present at earlier or later sessions.

The Venetian Ambassador, Francesco Foscari, reported that one of the cardinals who had been excommunicated by Pope Julius II, Bernardino Carvajal, Cardinal of Santa Croce in Gerusalemme, wrote to the Sacred College that he had been deprived contra raxon, and he demanded his rights. Cardinal Sanseverino also wrote to the Sacred College from Lyon that he wished to enter the Conclave along with the other Cardinals. [Marino Sanuto 6, 38] In accordance with the last wishes of Julius II, neither was accommodated [Marino Sanuto 16, col. 11]. This severely diminished the influence that Louis XII would have inside the Conclave.

Opening Ceremonies

The Mass of the Holy Spirit was celebrated by Cardinal Bakócz on Friday, March 4, in S Peter's Basilica in the Chapel of S. Andrew (Chapel of Pius III). The oration pro pontifice eligendo was delivered by the Bishop of Castellamare (1503-1537), Pietro de Flores. In the late afternoon (circiter XVIII) the entry procession took place, and the Conclave was enclosed sub horam XXII, through the actions of the Cardinal Chamberlain (Riario), Cardinal Luis d' Aragona, and Cardinal Farnese. On that same evening, Cardinal Adriano de Castello arrived. The Venetian Ambassador, Francesco Foscari, reported that the Imperial Ambassador, Count Alberto da Carpi (representing Empero Maximilian) and Hieronymo Vich (representing Ferdinand of Aragon), had gone the rounds of the cardinals' cells, advising each one not to elect the Venetian Cardinal Grimani [Marino Sanuto 16, 37-38]. The odds on Grimani, nonetheless, were 2:1 [Marino Sanuto 16, column 27].

On Saturday, March 5, the Mass of the Holy Spirit, with Gloria and Credo, was sung in the Chapel by the Sacristan, Gabriele Foscus, OESA, Archbishop of Durazzo (1511-1533). The cardinals then retired to a more distant hall and began working on the Electoral Capitulations. At the same time the conclavists assembled in another room to prepare their requests in consideration of their service in the Conclave.

On Sunday, March 6, according to Papebroch's anonymous conclavist, Cardinal de' Medici participated in the discussions in Congregation. But he was seriously ill with a fistula, and was about to be operated on. A surgeon was admitted to the Conclave for the purpose. After the operation, when he tried to leave, there was opposition to breaking conclave for him. In the afternoon the Cardinals assembled again and tried to come to some conclusions about the Electoral Capitulations. Prospero Colonna, who was in contact with Louis XII, came to the conclave entrance with the purpose of informing the Cardinals that the French cardinals along with the schismatic cardinals were on their way to Rome. But the Ambassadors who were guarding the Conclave would not let him proceed [Petruccelli I, 488-489].

On Monday, March 7, the Cardinals continued working on other clauses of the Capitulations, while Paris de Grassis summoned the conclavists so that they could write out their requests. Thomas Fedra Inghirami, the Secretary of the Conclave, was at hand for the writing. On the 8th, having completed their work, a delegation of four conclavists called upon the Cardinals to ask them to confirm their document and subscribe to it. The cardinals approved the document and signed it, but afterwards, absent the conclavists, they strongly criticized it. Neither the Electoral Capitulations nor the List of Graces was made public.

On March 9, the Venetian Hieronymus Grasso, who was in Rome, wrote to his correspondent Leonardo Grasso in Venice that the two leading candidates were Medici and Grimani, but that twelve cardinals considered themselves papabili [Marino Sanuto 16, 38]. The Electoral Capitulations were finally signed by all the cardinals on Wednesday, March 9, in a meeting in the Chapel of S. Nicholas. They also swore the oath to observe its provisions [The Florentine ambassadors heard news, wrongly it seems, that the Capitulations were signed on the 7th: Petruccelli, p. 489]. It addressed such matters as a Turkish war, cardinalatial income, reformation of the Roman Curia, and a regulation that a two-thirds vote of the cardinals was necessary to expel a member or to admit new cardinals, or for the appointment of Legates a latere or certain other high officials. The Florentine diarist Luca Landucci [Diario fiorentino, p. 338 ed. del Badia] saw a copy of the Capitulations on April 12 in Florence; he reported that there were 30 capitulations altogether, including:

– That there could not be more than two cardinals of the same blood, and that there could not be more than 24 cardinals, always elected by two-thirds vote of the Cardinals;

– That there had to be a General Council to reform the Church and to promote a Crusade against the infidel, and that the Capitulations had to be read in Consistory twice a year.

– That the Roman Curia could not be moved out of Rome to some place in Italy without the consent of a majority of the Cardinals, and could not be moved outside Italy without the consent of two-thirds of the Cardinals.

Only when they had made an agreement that could not be honored and would certainly be voided by the new pope, but which gave everyone a clearer view of where candidates stood on various issues, the cardinals were prepared to begin voting.

The bull of Julius II against simony (de simoniaca electione of January 14, 1505) was read on Thursday, March 10. It had recently been reenacted by the pope, on February 16, 1513, after having received the approval of the Fifth Session of the Lateran Council [Paris de Grassis, Diarium, in Gattico I, p. 315; Marino Sanuto 15, column 560]. In stark contrast with the Conclave of 1503, and in obedience to Pope Julius II's bull against the practice (translated by Berthelet, 38-45), there was no simony at the Conclave of 1513. Indeed, the general feeling was that the richest cardinals, who had the most largesse to dispense in exchange for votes, had the least chance of succeeding. The Venetian candidate was Cardinal Grimani, but he was opposed by the representatives of both the Emperor Maximilian and King Ferdinand of Spain. Spain preferred Cardinal Riario, while the Imperial interest backed Cardinal Castellesi (Adriano di Castello).

While the Cardinals began their first scrutiny, the conclavists were assembled by the Masters of Ceremonies in the Sistine Chapel to swear their oaths to their own petition.

Negotiations and Scrutinies

An explanation of the Conclave is presented by Paulus Jovius in his Life of Pope Leo X:

Caeterum ubi in conclave statim est receptus, in partes suas sibi iampridem conciliatos iuniores cardinales pertraxit. Erant ii regis ac illustribus maxime familiis nati, aetate opibusque florentes et imprimis Ludovicus Aragonius, Sigismundus Gonzaga, Marcus Cornelius et Alfonsus Petrucius, quibus accesserant Bendinellus Saulius et Matthaeus Sedunensis; multi etiam ex senioribus ea lege suffragia promittebant, ut et ipsi quum exirent candidati, paribus suffragiis iuvarentur. Erat tum senatus princeps Raphael Riarius, qui aetatis honore, sacerdotiis atque opibus caeteros omnes anteibat, quanquam ei deerant literae atque eae virtutes, quae multo luculentius quam ipsae divitiae honestum sacerdotem ad Christianam laudem exornant. Is in magnam spem adipiscendi pontificatus ab aura populari et tot circunfusis adulatoribus facile pervenerat. Sed eum ambientem et singulos prehensantem, cum ipsi iuniores eludebant, qui Ioanni candidato paratis firmisque suffragiis praesto aderant, tum etiam ei seniores plerunque fidem fallebant, quum quisque spes suas aleret et privatis rationibus compositis ad summi fastigii fortunam enitendum arbitraretur. Petebant enim ferme omnes, uti quisque erat aut studio principum, aut urbana gratia, aut opibus et doctrina maxime conspicuus. Ita dum quisque senior ante omnia sibi uni praecipue studet, et propterea cunctatius aliis suffragatur, Ioannem iuniores pontificem efficiunt, qui rei Christianae imperium dare potius quam accipere una perpetua consensione decreverant.

Accessit ad eum ante alios Franciscus Soderinus, qui uti erat inimicus admodum capitalis propter Petrum fratrem Florentia pulsum, ab initio eum omnibus adhibitis machinis oppugnarat, moxque perspecta iuniorum constantia, uti cautissimus senex in gratiam opportune redierat. Accessit et ipse Raphael et caeteri demum omnes, adeo sedatis propensisque animis, ut nequaquam simulanter effuse laetarentur, quod eum pontificem legitimis et longe simplicissimis comitiis creassent, qui nobilitate familiae, morum gravitate, exquisitisque literis et singulari naturae lenitate, non cardinales modo, sed cunctos fere mortales anteiret. Fuere qui existimarent vel ob id seniores ad ferenda suffragia facilius accessisse, quod pridie disrupto eo abscessu qui sedem occuparat, tanto fetore ex profluente sanie totum comitium implevisset ut tanquam a mortifera tabe infectus, non diu supervicturus esse vel medicorum testimonio crederetur.

Giovio points out that a number of the Cardinals at the Conclave were drawn from prominent aristocratic families: Luis d'Aragona, Sigismondo Gonzaga, Marco Cornelio, and Alfonso Petrucci, as well as Bendinelli Sauli and Matteo Lang. Rafaello Riario outshone them in in age and wealth, although he was no scholar, and lacked the virtues appropriate to an honorable Christian priest. He had a great expectation of winning the papacy, however, based on his popularity and the influence of his flatterers. He was going the rounds, talking to each cardinal privately (though the younger cardinals, who were committed to Cardinal de' Medici, were eluding him [the word eludere has multiple connotations: 'staying away from him', 'avoiding committing to him', 'playing with him']. The older cardinals each had his own ambitions, and had reasons to believe that he would become pope. Francesco Soderini came over to Medici—which was a great surprise, since the Medici were responsible for the explusion of his brother Pietro from Florence. Then Raffaele Riario, and at length all the rest (of his faction?), acknowledging his many virtues. Some thought that the seniors came over to Medici on account of this. That at least is Giovio's view. It is written in a beautiful Latin, to be sure, and it is neatly told, but, as usual with Giovio, it is in the tradition of ancient biography, far too interested in character portrayal (with its centering on virtues and vices) than sequential narration of the facts and dates, to be useful.

On Thursday, March 10, a scrutiny was held, but by agreement there was no accessio, since it was clear that no one would have a majority. And that was the case: in hoc scrutinio non fuerunt inventa tot suffragia, quot electioni sufficerent [Paris de Grassis, Diarium, in Gattico I, p. 315 column 1]. Cardinal Serra received 14 votes, Cardinal della Rovere 8, Cardinal Accolti 7, Bakócz 7, Fieschi 6, Finale [Finarii, Card. Caretto] 6, Grimani 2, and Medici 1 (A cardinal could name more than one candidate on his ballot). (An anonymous conclavist gives Cardinal Serra 13 votes [Papebroch, 150]). It was reported by the Florentine ambassadors that Cardinal Bainbridge had secretly passed out of the Conclave, in a plate which was being returned, a note in English, which read "S. Giorgio or Medici". The most interesting thing about the numbers is that the man who was saluted as the next pope at sundown received only one vote on the scrutiny in the morning. In the first day's voting, it is obvious that the votes given to Cardinal Serra were not serious. He was eighty-five years old, and was in no sense papabile.

But there were actually two groups among the cardinals, the seniors, creations of Sixtus IV and of Innocent VIII, led by and supporting Cardnal Riario—however dubious his gifts; and the junior group, who, it was soon discovered, supported Cardinal de' Medici. The senior cardinals and the papabili, according to the anonymous conclavist [Papebroch, 150E], were in a state of consternation when they saw the votes, non valentes comprehendere quid tractaretur, eo quod tractatus essent admodum secreti. It is not unlikely, therefore, that the thirteen votes for Serra were actually the supporters of Medici, who were not yet prepared to reveal their actual strength by voting for Medici outright. This was understood by the Imperial Ambassador, the Conte de Carpi, who remarks that only three more votes would have made Cardinal Serra pope, contrary to the desire of those who had voted for him [Petruccelli, 494]. Revelation of Medici's actual support might have produced active opposition. No doubt, if a second scrutiny had to take place in the absence of a secret agreement, those thirteen votes would have been differently deployed, and would have found their way to an equally unlikely papal candidate. Apparently Medici did not yet have the sixteen votes needed to make him pope. He did, however, have sufficient strength to deny the election to anyone else.

Late that afternoon, Cardinal de'Medici and Cardinal Riario the Chamberlain were seen in the middle of the Great Hall (Sala Regia?) in intense conversation that lasted for more than an hour. This must be the approach that Paolo Giovio was talking about. No one knew, however, what was going on, at least as far as the anonymous conclavist was aware. Around sundown, though, it became apparent that Cardinal de'Medici would be elected. His long discussion with Riario had likely drawn Riario and several votes from the seniors into his following.

The Florentine ambassadors, in a report of March 11, the day of the election, give credit of some kind to Cardinal Robert Guibé: Le cardinal de Nantes a servi notre Seigneur très-bien en cette élection [Petruccelli, 493]. The Imperial Ambassador, the Count de Carpi, remarked in a dispatch of the same day that the older cardinals had been beaten by the younger cardinals, who were unanimous in their deliberations. In addition, Cardinal Adriano di Castello had been particularly vocal in his opposition to Riario; and the Ambassador himself had been working through Cardinal Schiner to elect neither a French supporter nor a Venetian one. He also attributes a prominent role to Soderini (as did Paolo Giovio) though he is equally unclear as to when and under what circumstances Soderini came over to Medici. But he does say that Soderini's change of party influenced the Cardinal of San Vitale, Ciocchi del Monte, to do the same [Petruccelli, 493].

De Grassis noted that Cardinals kept coming up to Medici, who was in the great hall, and kissing him as though he were already the new pope. Some of them even called him "Beatissimus Pontifex", which caused Paris de Grassis to remonstrate. Finally, Medici was conducted to his cell by all the cardinals. Someone asked him what name he was going to use, but he replied that he did not know, and would think on it during the night.

Election of Cardinal de' Medici

Next day, at first light on Friday, March 11, some Cardinals called on Medici and urged him to hurry so that they could get the business done. Mass was celebrated in the Chapel of S. Nicholas, even before the sun was up, and then the Cardinals settled down to a written scrutiny. Since Medici was the senior Cardinal Deacon, it was his office to read the ballots as they were drawn from the chalice, which he did with complete modesty and calm. Cardinal Giovanni de'Medici, at the age of 37, was elected. The Masters of Ceremonies and others were summoned and the Act of Election was drawn up. Cardinal Sansone Riario, the Chamberlain, presented the ring of the Fisherman, the one which had been worn by Julius II. The Pope was then seated on a throne, and presented with writing instruments with which he signed the Electoral Capitulations (again), which were offered to him by Riario and Farnese. The Masters of Ceremonies inquired as to his throne name. Medici replied that he did not care, and would leave it to the Cardinals. The Cardinals, however, pressed him to make the choice, and he allowed that he had been thinking of Leo X. They immediately showed their approval, and then proceeded to the first adoration. Cardinal Farnese, who was now the senior Cardinal Deacon, then made the public announcement of the Election. The new Pope was then carried in the sedia gestatoria to the Basilica of S. Peter's where the second adoration took place at the high altar, Cardinal Riario intoning the Te Deum. The Cardinals were then given permission to leave and return to their palaces in the City. The Pope was carried back to the Vatican Palace, which took between one and two hours because of the crush of people wanting to see and touch him.

His announcement of his election as Pope (Postquam Deus Maximus), dated March 14, 1513, and sent to the Doge of Venice, Leonardo Loredan, is given by Marino Sanuto (6, 50-51).

According to the Diary kept by Paris de Grassis, the Papal Master of Ceremonies,

Mortuo Julio II de Ruvere, convenientibus cardinalibus vigintiquinque in palatio Vaticano, post dies septem, scilicet die Veneris, undecima Martii, electus est Cardinalis Joannes Mediceus, natione Etruscus et patria Florentinus, prior diaconum cardinalium, qui nomen assumpsit Leonis decimi. In die Sancti Joseph, cuius festivitas incidit die Sabbati decima noni Martii in Basilica Vaticana a Cardinali Farnesio coronatus fuit. Die Lunae undecima Aprilis in Festo S. Leonis die anniversariae eius capturae apud Ravennam, facta solemni equitatione ad Lateranum porrexit sacrae possessionis causa.

Ordination, Consecration, and Coronation

On the 15th Leo X, who only held the rank of deacon at his election, was ordained priest by Cardinal Raffaele Sansoni Riario, the Bishop of Ostia. The issue was raised, however, whether Cardinal Riario, who had not yet received the pallium, could consecrate the Pope as a bishop. After extensive consultation, it was decided that, while still Cardinal Deacon before his ordination, he could present the pallium to Riario himself, and that solution was adopted [Paris de Grassis, in Gattico I, p. 362]. On the 17th the Electus was consecrated bishop [Sanuto, 57; Moroni 38, p. 36; Papebroch, p. 149; Cancellieri, p 61]; the Venetian ambassador in Rome remarks [Diarii di Marino Sanuto, col. 57) that he appointed as Protonotaries his nephew Innocenzo Cibo and his longtime friend Bernardo di Bibbiena. There were numerous other appointments on the same day, including Ludovico di Canossa, OCist., Bishop of Tricarico, as maestro di casa. Bernard Rossi, Bishop of Treviso, was reappointed Governor of Rome. He had already named as his secretaries Pietro Bembo and Jacopo Sadoleto.

On the 19th of March, 1513, the Feast of St. Joseph, he was crowned at the Basilica of St. Peter ante porticum et introitum dictae basilicae videlicet supra scalam marmoream in qua constructum fuerat quoddam tabernaculum ornatum sive solium elevatum, by Cardinal Farnese [See Paris de Grassis, Diarium p. 1 Armellini; Cancellieri, Storia de solenne possessi , p. 67].

On Monday, April 4, Pope Leo X held his first Consistory. Paris de Grassis, the Master of Ceremonies, was elected Bishop of Pisaurum (1513-1519), while retaining the position of Master of Ceremonies [Paris de Grassis, Il diario di Leone X, p. 1; Eubel III, 274].

On the thirtieth day after his election, April 11, Leo X took possession of the Lateran Basilica in one of the great pageants of the sixteenth century [Gattico I, p. 382-386; Cancellieri, pp. 61-84].

The Sixth Session of the Fifth Lateran Council took place on April 27, 1513, with Pope Leo X presiding. The Seventh Session took place on June 17, with the Pope again in attendance. The Eighth Session took place in December. The Ninth Session was held on Friday, May 5, 1514. The Tenth Session took place on May 4, 1515, and the Eleventh on December 19, 1516. The Twelfth (and last) session was held on March 16, 1517.

Bibliography

Electio Papae Leonis Dicimi. Anno MCCCC Tredecimo. Ordo Mansionum Reveren(dissimorum) D(omi)norum Card(inalium) in Conclavi existentium: assignatarum s(ecundu)m prophecias in Capella pontificia figuratas. (s.l., s.d.). [list of 29 cardinals]

Paris de Grassis, Il diario di Leone X (ed. Pio Delicati and Mariano Armellini) (Roma 1884) p. 1. Marino Sanuto, I diarii di Marino Sanuto Volume 15 and Volume 16 (edited by F. Stefani, G. Berchet and N. Barozzi) (Venezia 1886). G. Penni, Croniche delle magnifiche ed onorate pompa fatta in Roma per la creazione et incoronatione di P. Leone X. P. O. Max. (Roma: Silber 1513). Paulus Jovius (Paolo Giovio), Vita de Leonis X Book III, chapters 4-9. Storia de' Conclavi Tome 1 (Roma 1691) 177.

Joannes Baptista Gattico, Acta selecta caeremonialia Sanctae Romanae Ecclesiae Tomus I (Romae: Jo: Baptista Barbierini 1753). Daniel Papebroch Conatus chronico-historicus ad catalogum Romanorum Pontificum (Antwerp: Michael Knobbarus 1685) pp. 149-150.

Concilium Sanctum Lateranense novissimum (Roma: Jacobus Mazochius, July 31, 1521). Johannes Dominicus Mansi, Sacrorum Conciliorum nova et amplissima collectio Tomus Trigesimus Secundus [32] (Parisiis 1902).

Angelo Favronius, Leonis X Pontificis Maximi Vita (Pisa 1797) pp. 59-62; and pp. 270-274 [using de Grassis, Guicciardini, Bembo, Jovius, et al.]. Mandell Creighton, A History of the Papacy Volume IV: The Italian Princes: 1464-1518 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin 1887). Ludwig Pastor, The History of the Popes (edited R. K. Kerr) Volume 7 (London: Kegan Paul 1908) 15-28. Ludwig Pastor, Geschichte der Päpste Vierter Band, Zweiter Abteilung (Freibourg im Breisgau 1907) 690-711. Ferdinand Gregorovius, The History of Rome in the Middle Ages (translated from the fourth German edition by A. Hamilton) Volume 8 part 1 [Book XIV, Chapter 3] (London 1902) 175-178. On Julius II's bull, see J. B. Saegmüller, Die Papstwahlen und die Staadten vom 1447 bis 1555 (Tübingen 1890), 7-10; and for the conclave, pp. 137-141.

For the schismatic Cardinals: Gaetano Moroni Dizionario di erudizione storico-ecclesiastica 10 (Venezia 1841) 19; and Pastor, The History of the Popes (edited R. K. Kerr) Volume 6, pp. 329-335. Mandell Creighton A History of the Papacy Vol. IV (Boston 1887), pp. 128-142.

On Cardinal Riario: Angelo Poliziano, "La congiura de' Pazzi," Prose volgari inedite et poesie latine e greche edite e inedite (edited by Isidoro del Lungo) (Firenze 1867), p. 94. Niccolò Machiavelli, History of Florence Book VIII, chapter 1. Moroni, Dizionario 57 (Venezia 1852). Charles Berton, Dictionnaire des cardinaux (1857) p. 1445. Erich Frantz, Sixtus IV und die Republik Florenz (Regensburg 1880) 197-230, especially 207. William Roscoe, The Life and Pontificate of Leo X (revised by Thomas Roscoe) Volume II (London 1900) pp. 69-77. Gregorovius (ibid.), pp. 226-232. On the papal bull and the Lateran Council, M.-A.-J. Dumesnil Histoire de Jules II (Paris 1873) 249-251, and Pastor, Volume 6, p. 440. Giovanni Berthelet, La elezione del papa: storia e documenti (Roma 1891).

On Bernardo Dovizi da Bibbiena: Angelo Maria Bandini, Il Bibbiena, o sia il Ministro di stato delineato nella vita del Cardinale Bernardo Dovizi da Bibbiena (Livorno 1758). A. Santelli, Il cardinal Bibbiena (Bologna 1931). G. L. Moncallero, Il cardinal D. da Bibbiena umanista e diplomatico (1470-1520) (Firenze 1953).

Albert Büchi and E.F.J. Mueller, Kardinal Matthäus Schiner als Staatsmann und Kirchenfürst, [Collectanea Friburgensia. Neue Folge. Lfg. 18, 23]. Albert Büchi, Korrespondenzen und Akten zur Geschichte des Kardinals Matthaeus Schiner. Bd. 1, Von 1489 bis 1515 (Basel : R. Geering, 1920) [Quellen zur Schweizer Geschichte, neue Folge, Abteilung III, 5]. Paul Legers, Kardinal Matthäus Lang (Bonn 1906). Franz Paul Datterer, Des Kardinals und Erzbischofs von Salzburg Matthäus Lang. Verhalten zur Reformation von Beginn seiner Regierung 1519 bis zu den Bauernkriegen 1525 (Universität Erlangen, 1890). Alons Schulte, Kaiser Maximilian I. als Kandidat für den päpstlichen Stuhl, 1511 (Leipzig 1906).

William E. Willkie, The Cardinal Protectors of England: Rome and the Tudors before the Reformation (CUP Archive 1974), pp. 40 ff. David Sanderson Chambers, Cardinal Bainbridge in the Court of Rome, 1509-1514 (Oxford: OUP 1965). Jervis Wegg, Richard Pace: A Tudor Diplomatist (London: Methuen 1932). M. Bibiana Pahlsmeier, The Diplomatic Career of Richard Pace, Secretary to Henry VIII (Washington DC 1941). On Cardinal Adriano Castello da Corneto: William Maziere Brady, Anglo-Roman Papers (London: Alexander Gardner 1890), 11-29.