SEDE VACANTE 1758

May 3, 1758—July 6, 1758

|

AG

|

|

|

|

AG SEDE • VACAN | TE • MDCCLVIII Shield with the Coat of Arms of Girolamo Card. Colonna, Camerlengo of the Holy Roman Church, upon the Cross of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem, crossed keys above, surmounted by Cardinal's hat with six tassels on each side; the Ombrellone over all. |

|

Berman, p. 187 #2887. |

GIROLAMO CARDINAL COLONNA DI SCIARRA (1708-1763), son of Francesco Colonna (4th Prince of Carbognano) and Vittoria Salviati, belonged to the celebrated

Roman family of the Colonna, only one of whose members, Martin V, ever became pope. He became a Cardinal deacon on September 9, 1743, delaying his reception of minor orders until 1746; he became Cardinal Deacon of S. Angelo in Pescheria (1743–1753);

he was appointed archpriest of S. Maria Maggiore. He was made Vice-Chancellor of the Holy Roman Church in 1753, and was appointed Camerlengo of the Holy Roman Church on September 20, 1756, a post he held until his death on January 18, 1763. He was Grand Prior in Rome of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem—hence the Maltese cross behind his stemma.

The Dean of the Sacred College of Cardinals was Raniero Cardinal d' Elci. He had been Nuncio to the French Court in the 1730's.

The Governor of the Conclave was the Prefect of the Apostolic Palaces, Monsignor Marcantonio Colonna (born in Rome August 16, 1724; died there December 4,1793), a member of the Roman nobility, A Neapolitan patrician, and a Venetian patrician. He was the son of Principe Don Fabrizio Colonna, 10th Prince and Duke of Paliano, and Caterina Salviati, daughter of the third Duke of Giuliano. He became a Cardinal in 1759, and was assigned the titulus of Santa Maria in Aquiro (which he exchanged for Santa Maria della Pace in 1762, and San Lorenzo in Lucina in 1764). Ordained in 1761, he was promoted titular Archbishop of Corinth in 1762, and became Vicar General of the city of Rome. He was made Archpriest of Santa Maria Maggiore (the Liberian Basilica) in 1775. In 1784 he was further promoted to the title of Cardinal Bishop of Palestrina.

|

AE

|

|

MARCVS•ANTON Inscription: "Marcus Antonius Colonna, Prefect of the Sacred Apostolic Palaces and Governor of the Conclave, 1758.". |

The Secretary of the Sacred College of Cardinals was Leonardo Antonelli of Senigaglia, utriusque signaturae Referendarius.

The Magistri Ceremoniarum were: Msgr. Ignatius Reali [Romanus], Msgr. Venatius Piersanti [Matelica], Msgr. Nuntius Sperandio [Aquila], Msgr. Franciscus Cajetanus Diversini [Romanus], Abate Joannes Lucca [Romanus], and Abate Joannes Baptista Valeriani [Romanus].

The Jesuit Problem

One of the Church's major problems was the Company of Jesus, the Jesuits. In the opinions of many of the rulers of Europe they were out of control, engaging in activities which were beyond what was expected of their own order, or the clerical calling, or the Church itself. These various activities, it seemed, were working to the detriment of the rulers, individually and collectively. The Jesuits, in their view, were manipulating the policies not only of the Catholic Church but of individual governments as well. To take just one example from 1757, the Jesuit Provincial in Paris, one Forestier, was providing secret information about the troubles of the French monarchy with the Church of France to Cardinal Albani, the leader of the Imperial faction at the Papal Court [Boutry, Choiseul à Rome, p. 294; cf. Benedict XIVs encyclical Ex omnibus of October 16, 1756, on the Church in France, at pp. 319-327]. As nationalism grew stronger and stronger and spread, the Jesuits were seen as its enemy. The Bourbon family, whose members ruled in a number of capitals, including Paris and Madrid, had decided that their Family Compact required them to strike at these priests who were threatening the family's joint interests. The Marquis de Pombal, the Portuguese first minister, put his complaints against the Jesuits into a memorandum of October 8, 1757, and again in a second, of February 10, 1758, which he sent to the Portuguese Minister in Rome to present to Pope Benedict XIV [Collecção dos Negocios de Roma no Reinado de El-Rey Dom Jose I. Ministerio do Marquez de Pombal e Pontificados de Benedicto XIV e Clemente XIII. 1755-1760 Parte I (Lisboa 1874), 41-48]. The Jesuits (even in their own view) were also the subjects of attack coming from the various secret societies (the Masonic lodges in particular), whose ideals of individual liberty and the control of religious organizations by the State were at variance with the founding charter of the Company of Jesus. The principle of the Universal Sovereignty of the Pope was being set against the Power of the State. Under pressure from Portugal (the Conde de Pombal), supported by Bourbon Spain and Bourbon France, the Pope was compelled to intervene in the Jesuit situation. On April 1, 1758, Pope Benedict XIV had taken a fateful decision. He signed a letter addressed to Cardinal Francisco de Saldanha da Gama, authorizing him to act as "Visitor and Reformer of the Clerics Regular of the Compañia de Jesus in the Kingdoms of Portugal and the Algarve, and the domains and provinces of the two Indies.... tam in capite quam in membris. " On June 7, 1758, the Patriarch of Lisbon, José Manoel de Cãmara, suspended all Jesuits within the Patriarchate from preaching or hearing confessions [Collecção dos Negocios de Roma no Reinado de El-Rey Dom Jose I., p. 59].

Benedict XIV (Lambertini) had pursued a policy of political neutrality among the various states in Italy and in Europe in general. This policy had been sorely tested by the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748), which had brought Prussia onto the political stage of Europe as a major figure, pitting Prussia and England against Austria and France. Frederick the Great was able to use Catholic Bavaria against both the Empire and France, by supporting the Elector for the Imperial crown as an alternative to Maria Theresa's husband Franz. A coalition was formed to put a stop to Prussia's growing power and expansion. It included Austria, France, Russia, Sweden and Saxony; England, which was fighting France in the French and Indian War, again supported Prussia. The Seven Years War broke out in August, 1756. On the previous December 6, 1757, the Austrian army of some 80,000 men had been thoroughly defeated at the Battle of Leuthen. As the Conclave was meeting, the Russians had invaded East Prussia and advanced as far as the Oder River, and King Frederick had again invaded Moravia and attempted to besiege Olmütz. The French had crossed the Rhine, but were repelled by Ferdinand of Brunswick, who defeated them at Crefeld on June 23. Frederick of Prussia defeated the Russians at Zorndorf on August 25, while in the meantime the Austrians were attacking Frederick's brother Prince Henry in Saxony near Dresden. It was a busy, unpleasant, deadly Summer.

Beyond the political and military situation was the problem of the Enlightenment. Christianity had been challenged over the century gone by by Hobbes and Hume, Spinoza and Leibnitz, Diderot and D'Alembert, Rousseau and Voltaire, to name but a few. Ravignan believed that he could see an increased "violence et excitation" in Voltaire's correspondence as early as 1757 [Ravignan, Clément XIII et Clément XIV (Paris 1854), p. 23]. The Jesuits were doing their part to promote Catholic education, and it was their schools and colleges which were under particular attack [A. Theiner, Histoire des Institutions d' éducation ecclésiastique I, pp. 366-367; endorsed by Ravignan, pp. 20-21]:

Il ne manquait pas d'hommes clairvoyants en France, qui prévoyaient le mal irréparable qui résulterait, non-seulement pour leur patire, mais encore pour tous les États catholiques, si l'on ne s'appliquait avec vigeur et énergie a faire échouer le complot impie des encyclopédistes et à contrecarrer leur tendance irréligeuse. Cette tendance se dévoile mieux dans leur combat contre la société de Jésus.... Le grand obstacle qui s'opposait encore a l' exécution d'un si vaste plan, était la société de Jésus, à cause de son grand zèle pour la religion, de son influence sur l'esprit de la jeunesse, de la grande estime qu'avaient pour elle les souverains, et enfin à cause du respect inébranlable qu'elle ne cessait de professer poour la chaire de saint Pierre. Voltaire reconnut tout cela, et en conséquence dirigea tout la force de ses armes contre l'ordre des jésuites, qu'il regardait comme le seul appui qui soutenait le christianisme.

But Catholic responses to the Enlightenment only brought greater scorn upon the Church for its threadbare medieval intellectual tatters and its inquisitorial methods. The new Pope, Clement XIII, for example, thought it a good idea to issue a Bull, Ut Primum, on September 3, 1759, condemning and forbidding people to read the Encyclopédie—as though they would [Barberi and Spetia (editors) Bullarii Romani continuatio I (Romae 1835), p. 222, no. LXXIV]. The Decrees of the Council of Trent had been intellectually obsolete on the day the Council adjourned for the last time, and the repetition of formulae had not slowed Protestantism or impressed intellectuals. Free-thinking was the order of the day. Freemasonry had, of course, been condemned by the Papacy, by Clement XII's Bull In eminenti of April 28, 1738 [Bullarium Romanum Turin edition 24 (1872), CCXXIX, pp. 366-367], and numerous books had been placed on the Index of Prohibited Books. But the effect was nugatory.

Pope Benedict XIV began to show symptoms illness on April 26, 1758. He had a fever, which aggravated his asthma, and he had difficulties in urinating. The last symptom was part of his kidney disease which manifest itself in his lengthy acquaintance with gout (podagra) [Montor, 109]. His hearty appetite, however, was not affected. But on May 3, 1758, aged eighty-three, he died [reports of the Count of Rivera to Cavaliere Ossorio, minister of the King of Sardinia, in Petruccelli IV, 137].

During this Sede Vacante, the ninth day of the Novendiales was not observed, since it fell on Pentecost Sunday, the celebration of which took absolute precedence. Pope Benedict's funeral oration was pronounced by Msgr. Tommaso Antonio Emaldi, Professor of Canon Law at the Sapienza and Canon of the Lateran Basilica, who was Secretary of Latin Briefs to Benedict XIV.

The Cardinals

Twenty-seven of the fifty-five cardinals entered conclave on the opening day. Five cardinals who were in Rome that day did not enter conclave due to illness; one, Mesmer, never entered at all, while the other four entered on June 29, when Cardinal von Rodt, the Imperial ambassador, arrived. Ten cardinals did not participate at all. Cardinal de' Bardi had originally joined the conclave, but he left on June 24. There were, therefore, forty-four electors in the later stages of the conclave. Thirty votes were needed for a canonical election.

An official list of the Cardinals and their Conclavists and dapiferi who participated in the Conclave of 1758 is contained in the Motu Proprio Nos volentes of Clement XIII (July 11, 1758) [Bullarii Romani continuatio (ed. A. Barbieri and A. Spetia) Tomus primus (Romae 1835), pp. 7-8 and 15-17].

-

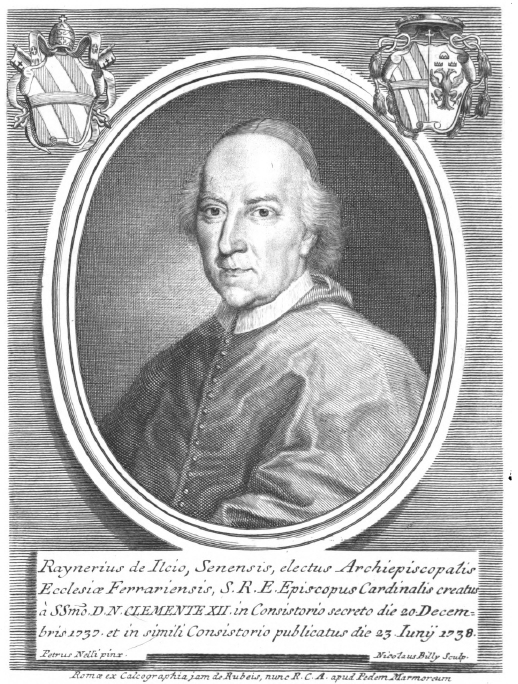

Rainiero Pannocchieschi D'Elci (de Ilcio) (aged 88) [Florentinus, Senensis], son of Filippo, Marchese Monticiani, and and Francesca Torrigiana; his uncle was Francesco Pannocchieschi d'Elci, Archbishop of Pisa (1663-1702). Doctor of law (Siena). He took up the practice of law in Rome. On May 27, 1700 he was named Referendary of the Signatures of Justice and Grace. In 1701 Pope Clement XI named him Pro-Legate in the Province of Aemilia; after four successful years, he was transferred to Fano as Governor. He returned to Rome and was appointed to the SC of the Consulta. In 1711 he was appointed Inquisitor of Malta. On his return, he was made a Cleric of the Apostolic Camera. He was promoted Prefect of the Archives, then Prefect of the Ripae, and then Prefect of Grace. Bishop of Ostia e Velletri, Dean of the Sacred College of Cardinals. In 1719 he was appointed Vice-Legate of Avignon, where he did everything possible to mitigate the effects of the plague of 1721. He was then appointed Nuncio in France (1731-1737), and consequently named Archbishop of Rhodes (1730-1738). On December 20, 1737 he was created cardinal by Pope Clement XII (Corsini), with the title of S. Sabina (1738–1747). On May 5, 1738, he was appointed Archbishop of Ferrara (1738-1740); episcopal duties, however, were not to his taste, and he unsuccessfully petitioned Clement XII to remove the burden from him; Benedict XIV, however, allowed him to resign, but immediately appointed him Apostolic Legate in Ferrara for a three-year term. In 1747 he was promoted to the Seat of Bishop of Sabina, while retaining the title of S. Sabina (1747-1761). He advanced to the See of Porto e Santa Rufina (1753–1756), and then Ostia–Velletri (1756–1761), and Dean of the Sacred College of Cardinals. He died on June 22, 1761, at the age of 90, and was buried in the title of S. Sabina on the Aventine [Vincenzo Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma VII, p. 321 no. 662]. [engraved portrait at right]

Rainiero Pannocchieschi D'Elci (de Ilcio) (aged 88) [Florentinus, Senensis], son of Filippo, Marchese Monticiani, and and Francesca Torrigiana; his uncle was Francesco Pannocchieschi d'Elci, Archbishop of Pisa (1663-1702). Doctor of law (Siena). He took up the practice of law in Rome. On May 27, 1700 he was named Referendary of the Signatures of Justice and Grace. In 1701 Pope Clement XI named him Pro-Legate in the Province of Aemilia; after four successful years, he was transferred to Fano as Governor. He returned to Rome and was appointed to the SC of the Consulta. In 1711 he was appointed Inquisitor of Malta. On his return, he was made a Cleric of the Apostolic Camera. He was promoted Prefect of the Archives, then Prefect of the Ripae, and then Prefect of Grace. Bishop of Ostia e Velletri, Dean of the Sacred College of Cardinals. In 1719 he was appointed Vice-Legate of Avignon, where he did everything possible to mitigate the effects of the plague of 1721. He was then appointed Nuncio in France (1731-1737), and consequently named Archbishop of Rhodes (1730-1738). On December 20, 1737 he was created cardinal by Pope Clement XII (Corsini), with the title of S. Sabina (1738–1747). On May 5, 1738, he was appointed Archbishop of Ferrara (1738-1740); episcopal duties, however, were not to his taste, and he unsuccessfully petitioned Clement XII to remove the burden from him; Benedict XIV, however, allowed him to resign, but immediately appointed him Apostolic Legate in Ferrara for a three-year term. In 1747 he was promoted to the Seat of Bishop of Sabina, while retaining the title of S. Sabina (1747-1761). He advanced to the See of Porto e Santa Rufina (1753–1756), and then Ostia–Velletri (1756–1761), and Dean of the Sacred College of Cardinals. He died on June 22, 1761, at the age of 90, and was buried in the title of S. Sabina on the Aventine [Vincenzo Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma VII, p. 321 no. 662]. [engraved portrait at right] - Giovanni Antonio Guadagni, OCD (aged 83) [Florentinus], Bishop of Porto e Santa Rufina (died January 15, 1759). Bishop of Arezzo (1724-1732). Vicar of Rome.

- Francesco Scipione Maria Borghese (aged 61) [Romanus], son of Marcantonio Borghese, Prince of Rossano and Sulmone, and Livia Spinola, daughter of Carlo Spinola, Prince of Sancto Angelo. Doctor of Laws (Roman Archiginnasio). Praefectus cubiculo Apostolico. Titular Archbishop of Trajanopolis in Thrace. Created cardinal on July 6, 1729. Bishop of Albano (died June 21, 1759).

-

Giuseppe Spinelli (aged 64) [Neapolitanus]; son of Giovanni Battista Spinelli, Marchese Fuscaldi, Prince of S. Arcangelo, and Maria Imperiali daughter of the Prince of Francavilla; Giuseppe's brother Tommaso was the Marchese Fuscaldi. Bishop of Palestrina. He was placed in the Seminario Romano at the age of 13. Cameriere segreto to Clement XI. Sent to Vienna in 1719 with the red biretta for Cardinal Giorgio Spinola. In 1720 he was Inter-Nuncio in Flanders, where he remained until 1725. In that year, the government of Flanders was entrusted to Maria Elizabeth of Austria, the sister of the Emperor Charles VI, and Spinelli was promoted to Nuncio and made titular Archbishop of Corinth in Greece in the Ottoman Empire. He returned to Rome in 1731 and was appointed Secretary of the SC of Bishops and Regulars. In 1734 he was appointed Archbishop of Naples. Created a cardinal on January 17, 1735, by Pope Clement XII. He resigned the archbishopric in 1754, and was succeeded by Cardinal Sersale. In Rome he became Prefect of the SC de propaganda fide (1756-1763). Protector of the Romitani and of the Scots. In 1753 he was named Bishop of Palestrina. He died on April 12, 1763, and was buried in the Basilica XII Apostolorum [V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma II, p. 283 no. 870]. In 1758, Spinelli had placed himself in the leadership of the group called the Zelanti [Boutry, Choiseul à Rome, p. 270]

- Carlo Maria Sacripante (aged 68) [Romanus], Bishop of Frascati (died November 4, 1758).

-

Joaquín Fernández Portocarrero Mendoza (aged 77) [Madrid], of the family of the Marchesi di Almanaro. He joined the Knights of Malta, and was eventually promoted to be Admiral of Galleys. He was appointed the Order's ambassador to Charles VI, who, in 1722, appointed him to the post of Viceroy of Sicily. He served in that capacity for six years, and then decided to go to Rome and take holy orders. Clement XII appointed him titular Latin Patriarch of Antioch (1735-1743). He was created cardinal by Benedict XIV on September 9, 1743. Cardinal Priest of SS. Quattro Coronati (1743–1747). Cardinal Priest of S. Cecilia (1747–1753). Cardinal Priest of S. Maria in Trastevere (1753–1756). Bishop of Sabina (1756-1760) He died in Rome on June 22, 1760, at the age of 79. He was buried at S. Maria in Aventino, the Priory in Rome of the Knights of Malta [V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma VII, p. 263 no. 532].

-

Carlo Rezzonico (aged 65) [Venetian], Conte di Piove di Sacco. Cardinal Priest of S. Marco. Bishop of Padua. According to the French ambassador, Choiseul, he was “un homme de mérite dans son état et propre à la papauté s'il n'était pas Vénitien” [Boutry, Choiseul à Rome, p. 247]. Doctor in utroque iure (Padua). Governor of Fano (1724). Bishop of Padua (1743-1758). Bishop of Rome (1758-1769). (died February 2, 1769). He was the only Venetian at the Conclave, but he had been created cardinal without Venetian support. He was not clearly associated with either the Bourbons or the Hapsburgs.

-

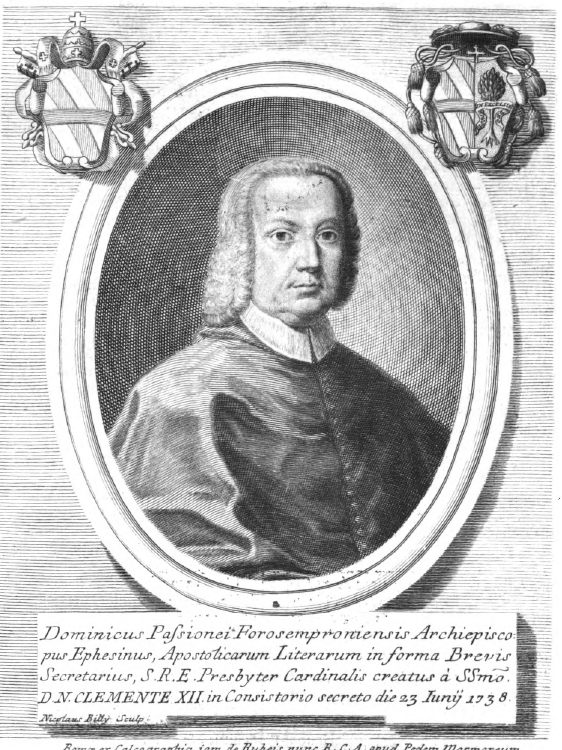

Domenico Passionei (aged 75) [born at Forum Sempronii, Fossombrone, December 2, 1682], son of Conte Giovanni Benedetto Passionei, and Virginia Sabbatelli. Cardinal Priest of S. Prassede and of S. Bernardo alle Terme in commendam . At the age of 13 he was sent to Rome and put in the charge of his elder brother Guido, who was Secretary of the Cipher, Secretary of the College of Cardinals, and Secretary of the Consistorial Congregation. Domenico was sent to the Collegio Clementino, run by the Somaschi fathers. In 1701 he published a small volume of philosophical propositions, dedicated to Pope Clement XI. He then studied privately under the direction of Father Giuseppe Maria Tommasi di Lampedusa, Theat., a member of the Arcadian Academy [Crescimbeni, Vite degli Arcadi illustri III, pp. 21-75], who became a cardinal in 1712. He became a friend of Msgr. Giusto Fontanini, who was also a member of the Arcadian Academy [Domenico Fontanini, Memorie della vita di monsignor Giusto Fontanini,... scritte dall'abate Domenico Fontanini,... e divise in tre parti nelle quali, oltra varie notizie letterarie, si narrano molte cose, accadute sotto quattro pontefici Clemente XI, Innocenzo XIII. Benedetto XIII e Clemente XII. (P. Valvasense, 1755)]. In 1706 they published an edition of the Liber Diurnus. Domenico early attracted the attention of Magliabechi [a letter of March 1, 1704], also an Arcadian, and of the Dutch scholar Jacob Gronovius, formerly Professor of History at Pisa, with whom he corresponded on subjects of ancient history. He learned Greek, Hebrew and Syriac. In 1706 he carried the red biretta to Paris for Cardinal Filippo Gualtieri, on commission of Clement XI; he remained several years, discovering manuscripts and making the acquaintance of Bernard Montfaucon and Jean Mabillon. In 1708, still in Paris, he published a translation of S. Hippolytus, the disciple of S. Irenaeus. In 1708 he was in Holland, as France and the Emperor were negotiating the status of Catholics in that Protestant country (The Congress of Utrecht, which led to the peace between the Emperor and Louis XIV in 1714). Abbot of S. Michele Archangelo Lamularum. Utriusque Signaturae Referendarius. Nuncio extraordinary to Holland. He returned to Rome at the end of 1714. From 1716 to 1719 he spent time at home in Fossombrone, or in the library at Verona. In September of 1719 he was in Florence, where he was elected a member of the Accademia della Crusca. At the end of 1719 he was back in Rome, working in the Secretariat of the SC de Propaganda Fide. The new Pope, Innocent XIII, a member of the Arcadian Academy since 1719, appointed him Nuncio in Switzerland (1721-1730), in succession to Msgr. Giuseppe Firrau, for which purpose, on July 15, 1721, he was created Titular Archbishop of Ephesus in Ottoman Turkey. Nuncio in Vienna (1731-1738). Named Cardinal on June 23, 1738. Coadjutor-Librarian (1741-1755) to Cardinal Quirini (Bibliothecarius 1730-1755), then Bibliothecarius S. R. E. (1755-1761), Secretary of Briefs to Clement XII, Benedict XIII (a member of the Arcadian Academy since 1709), and Clement XIII. He died on July 5, 1761, at the age of 79, as his funeral inscription in S. Bernardo alle Terme indicates [V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma IX, p. 184, no. 369]. In the Conclave of 1758, he was a candidate favored by Maria Theresa. This was no surprise, considering his years spent in Holland and Vienna.

Domenico Passionei (aged 75) [born at Forum Sempronii, Fossombrone, December 2, 1682], son of Conte Giovanni Benedetto Passionei, and Virginia Sabbatelli. Cardinal Priest of S. Prassede and of S. Bernardo alle Terme in commendam . At the age of 13 he was sent to Rome and put in the charge of his elder brother Guido, who was Secretary of the Cipher, Secretary of the College of Cardinals, and Secretary of the Consistorial Congregation. Domenico was sent to the Collegio Clementino, run by the Somaschi fathers. In 1701 he published a small volume of philosophical propositions, dedicated to Pope Clement XI. He then studied privately under the direction of Father Giuseppe Maria Tommasi di Lampedusa, Theat., a member of the Arcadian Academy [Crescimbeni, Vite degli Arcadi illustri III, pp. 21-75], who became a cardinal in 1712. He became a friend of Msgr. Giusto Fontanini, who was also a member of the Arcadian Academy [Domenico Fontanini, Memorie della vita di monsignor Giusto Fontanini,... scritte dall'abate Domenico Fontanini,... e divise in tre parti nelle quali, oltra varie notizie letterarie, si narrano molte cose, accadute sotto quattro pontefici Clemente XI, Innocenzo XIII. Benedetto XIII e Clemente XII. (P. Valvasense, 1755)]. In 1706 they published an edition of the Liber Diurnus. Domenico early attracted the attention of Magliabechi [a letter of March 1, 1704], also an Arcadian, and of the Dutch scholar Jacob Gronovius, formerly Professor of History at Pisa, with whom he corresponded on subjects of ancient history. He learned Greek, Hebrew and Syriac. In 1706 he carried the red biretta to Paris for Cardinal Filippo Gualtieri, on commission of Clement XI; he remained several years, discovering manuscripts and making the acquaintance of Bernard Montfaucon and Jean Mabillon. In 1708, still in Paris, he published a translation of S. Hippolytus, the disciple of S. Irenaeus. In 1708 he was in Holland, as France and the Emperor were negotiating the status of Catholics in that Protestant country (The Congress of Utrecht, which led to the peace between the Emperor and Louis XIV in 1714). Abbot of S. Michele Archangelo Lamularum. Utriusque Signaturae Referendarius. Nuncio extraordinary to Holland. He returned to Rome at the end of 1714. From 1716 to 1719 he spent time at home in Fossombrone, or in the library at Verona. In September of 1719 he was in Florence, where he was elected a member of the Accademia della Crusca. At the end of 1719 he was back in Rome, working in the Secretariat of the SC de Propaganda Fide. The new Pope, Innocent XIII, a member of the Arcadian Academy since 1719, appointed him Nuncio in Switzerland (1721-1730), in succession to Msgr. Giuseppe Firrau, for which purpose, on July 15, 1721, he was created Titular Archbishop of Ephesus in Ottoman Turkey. Nuncio in Vienna (1731-1738). Named Cardinal on June 23, 1738. Coadjutor-Librarian (1741-1755) to Cardinal Quirini (Bibliothecarius 1730-1755), then Bibliothecarius S. R. E. (1755-1761), Secretary of Briefs to Clement XII, Benedict XIII (a member of the Arcadian Academy since 1709), and Clement XIII. He died on July 5, 1761, at the age of 79, as his funeral inscription in S. Bernardo alle Terme indicates [V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma IX, p. 184, no. 369]. In the Conclave of 1758, he was a candidate favored by Maria Theresa. This was no surprise, considering his years spent in Holland and Vienna. -

Camillo Paolucci Merlini (aged 65) [Forli], nephew of Cardinal Fabrizzi Paolucci, who was Secretary of State of Pope Clement XI. He studied law under Prospero Lambertini and obtained the Doctorate from the Archiginnasio Romano. He was made a Canon of the Lateran Basilica, and a member of the SC on Good Government. Nuncio to Poland (1728-1738), for which assignment he was consecrated titular Archbishop of Iconium in Turkey (1724-1743). Nuncio in Vienna (1738-1745). Cardinal Priest of S. Maria in Trastevere (1756-1758), with SS. Giovanni e Paolo in commendam (1746-1756). Legate in Ferrara. He died on June 11, 1763, at the age of 71, and was buried in S. Marcello [V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma II, p. 323, no. 1000]. He was believed to be too devoted to the French interest, and way way too devoted to his sister-in-law.

-

Carlo Alberto Guidobono Cavalchini (aged 74) [Tortona, near Alessandria], Cardinal Priest of S. Maria della Pace (1743-1759), created by Benedict XIV in his first consistory in 1743. Doctor of Laws (Pavia). Practiced law in Milan. Clement XI appointed him Consistorial Advocate in Rome in 1716. In 1725 he became one of the Voting Members of the Signatura. He then became Promoter of the Faith. He was promoted to Secretary of the Congregation of the Council, which brought with it episcopal consecration; he was named titular Archbishop of Philippi in Macedonia (1728-1743). He also became Canonist and Corrector at the Penitenzieria. He was promoted cardinal priest on September 9, 1743. Prefect of the Congregation of Bishops and Regulars (from 1748-1774; he did not cease in 1752, as alleged by G-Catholic, but still held the post in 1774). Member of the SC of the Inquisition, the Council, Immunity (a congregation founded on June 22, 1622, by Urban VIII, taking over tasks previously dealt with by the SC on Bishops (founded by Sixtus V on January 22, 1588), Examination of Bishops, Rites, and the Index. In the new Papacy he was named Pro-Datary (1758-1774). He died on March 7, 1774, at the age of 90, as Bishop of Ostia and Dean of the Sacred College. As far as electability was concerned, the former French Ambassador, the Duc de Choiseul, had pointed out that he was a subject of the King of Sardinia, he was in favor of the Constitution Unigenitus, he had been strongly in favor of the canonization of Cardinal Robert Bellarmine, his opinions on French ecclesiastical affairs were dangerous [Boutry, 266-267]. It was remarked against him in the Conclave of 1758 that he had chosen entirely the wrong conclavists to support his ambitions: his valet and his majordomo, Carlo Bonaglia and Carlo Alberto Guidobono. His clerical conclavist was a priest of Macerata, Giacomo Chiappini. They had no standing and no connections when it came to negotiating with papal princes.

-

Giacomo Oddi (aged 78) [Perugia]. Cardinal Priest of S. Anastasia. Doctor in utroque iure (Perugia, 1702). Referendary of the Signatura, Protonotary de numero participantium (1709). Governor successively of Sabina, Rimini, Fabriano, Ancona, Civitavecchia, and Viterbo (1724). As Apostolic Commissary, he was sent to adjust the differences between the Papacy and Parma. In 1733 he was promoted to the rank of Nuncio, which brought him a prelacy, the titular Archbishopric of Laodicea. He was subsequently Nuncio in Cologne and in Venice. In 1739 he was promoted to the Nunciature to Portugal. On September 9, 1743 he was named a Cardinal. He was appointed Legate in Urbino and then in Ravenna. Archbishop-Bishop of Viterbo e Toscanella (1749-1770). He died on May 2, 1770, at the age of 91, and was buried in the Church of the Jesuits in Viterbo. Oddi was despised by the Court of Naples, and a good deal of their hostility seeps into the interpretation of the Conclave of 1758 by Petruccelli.

-

Federico Marcello Lante della Rovere (aged 63) [Romanus], Cardinal Priest of S. Silvestro in Capite (1753-1759). Governor of Ancona (1728), where he struck up a friendship with Cardinal Prospero Lambertini, then the bishop of Ancona (1727-1731) and later, in 1730, Pope Clement XII. Nuncio Extraordinary to France, for which he was consecrated titular Bishop of Petra (1732-1743). In 1732 he was named President of Urbino (1732-1743). In 1743 he was raised to the Cardinalate with the title of S. Pancrazio (1745–1753). President of the territory of Balneario. In 1759 he was named Prefect of the SC of Good Government. Abbot Commendatory of Farfa. In 1763 he became Protector of England, and Protector of the English College in Rome. Protector of the Carmelites. He died on died March 3, 1773, at the age of 77, and was buried in the family chapel in the Church of S. Nicola da Tolentino near the Villa Margherita [V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma IX, p. 468 no. 951].

-

Marcello Crescenzi (aged 63) [Romanus], brother of Marquis Crescenzi. Cardinal Priest of S. Maria in Traspontina, Made a Canon of the Vatican Basilica by Innocent XIII, and appointed to the SC of Good Government. In 1724 he became Presidente of the Apostolic Camera (the fifth-highest official). In 1726 he was named an Auditor of the Rota. In 1739 he was transferred to the Nunciature of France, for which post he was consecrated titular Archbishop of Nazianzus in Turkey (1739-1743). He served as Nuncio in France for four years. In the Consistory of September 9, 1743, he was named Cardinal Priest and assigned the title of S. Maria in Traspontina (1743-1768). He was given membership on the SC of Bishops and Regulars, SC of the Council, SC of Immunity (a congregation founded on June 22, 1622, by Urban VIII, taking over tasks previously dealt with by the SC on Bishops (founded by Sixtus V on January 22, 1588), and SC de propaganda fide. Archbishop of Ferrara (1746-1768). He died on August 24, 1768, and was buried in the Cathedral of Ferrara.

-

Giorgio Doria (aged 49) [Genoa], Cardinal Priest of S. Cecilia He was named Vice-Legate of Bologna by Clement XII. He served four years as Governor of Ascoli. He was sent as Legate Extraordinary to Frankfurt am Main to the Imperial Diet, for which purpose he was consecrated titular Archbishop of Chalcedon in Ottoman Turkey (1740-1743). Created cardinal by Benedict XIV on September 9, 1743, and made Legate in Bologna, a post which he filled for ten years. He was also appointed to membership of the SC on Rites, the SC on the Council, and the SC de propaganda Fide. Prefect of the S.C. of Good Government (1754-1759). He was the Protector of the OESA (Augustinians). He died on January 31, 1759, at the age of 50, and was buried in S. Cecilia [V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma II, p. 42 no. 125]. The Duc de Choiseul thought that he had no talent for administration, and would make a bad Secretary of State [Boutry, Choiseul à Rome, p. 243].

- Giuseppe Pozzobonelli (aged 61) [Milan], Cardinal Priest of S. Maria in Via (died April 27, 1783). Archbishop of Milan (1743-1783).

- Girolamo de' Bardi (aged 73) [Florentinus], a cousin of Cardinal Corsini. Cardinal Priest of S. Maria degli Angeli (died March 11, 1761). [left the Conclave, due to illness, on June 24, 1758, and retired to Frascati on Tuesday, June 27]

-

Fortunato Tamburini, OSBCas. (aged 75) [Mutinensis], nephew of Michelangelo Tamburini, SJ, once General of the Jesuits (1704-1730). Cardinal Priest of S. Callisto (1752-1761), previously Cardinal Priest of S. Matteo in Merulana (1743–1753). Former Abbot of S. Paolo fuori le mura. Benedict XIII placed him on the SC of Index, and made him Qualificator at the SC of the Inquisition. Clement XII made him a Consultor to the SC of Rites. When he became cardinal he was named Prefect of the SC of Rites. He was also a member of the SC for the Examination of Bishops. Protector of the Cassinense Congregation of the Benedictine Order. He died on August 9, 1761, and was buried in S. Callisto [V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma XI, p. 523 no. 758].

- Daniele Delfino (aged 72) [Venetus], Cardinal Priest of S. Maria sopra Minerva (died March 13, 1762). First Archbishop of Udine (1752-1762).

- Carlo Vittorio Amedeo delle Lanze (aged 45) [Turin], Cardinal Priest of S. Sisto (died January 25, 1784). titular Archbishop of Nicosia.

- Henry Benedict Mary Clement Stuart (aged 33) [Romanus], Cardinal Priest of Ss. XII Apostoli (died July 13, 1807). Archpriest of the Vatican Basilica, Prefect of the Reverend Fabric of St. Peter's. "Cardinal York". "Il n' a pas le sens le plus commun; il ne peut pas arranger deux idées ensemble." [Duc de Choiseul, in Boutry, Choiseul à Rome, p. 248]

- Giuseppe Maria Feroni (aged 65) [Florentinus], Cardinal Priest of S. Pancrazio (1753-1764). Died November 15, 1767.

- Fabrizio Serbelloni (aged 62) [Bononiensis], Cardinal Priest of S. Stefano al Monte Celio (1754-1763) Legate in Bologna. Former Nuncio to Cologne (1734-1738), Poland (1738-1746), and Austria (1746-1753). Died December 7, 1775.

- Giovanni Francesco Stoppani (aged 62) [Mediolanensis], Cardinal Priest of S. Martino ai Monti (1754-1763). Legate in the Romagnola. Died November 18, 1774.

-

Luca Melchiorre Tempi (aged 70) [Florentinus], Cardinal Priest of S. Croce in Gerusalemme (1757-1762). Titular Archbishop of Nicomedia. Former Nuncio to the Netherlands (1736-1744) and Portugal (1744-1758). Died July 17, 1762. His sister's son, Luigi de' Bardi, was a secular Canon in the Cathedral of Florence (1735-1776).

- Carlo Francesco Durini (aged 65) [Mediolanensis], Cardinal Priest of SS. Quattro Coronati (1754-1769), Archbishop-Bishop of Pavia (1753-1769).

- Cosimo Imperiali (aged 63) [Genoa], Cardinal Priest of S. Clemente (1753-1759), former Vice-Camerlengo of the Holy Roman Church (1747-1753). In 1724 he was governor of Fermo. His confessor was Fr. Lorenzo Ricci, SJ, who was elected General of the Jesuits during the Sede Vacante.

- Vincenzo Malvezzi (aged 43) [Bononiensis], of the Counts of Selva. Cardinal Priest of Ss. Marcellino e Pietro (1753-1775). Ordained by Cardinal Prospero Lambertini, Archbishop of Bologna (later Benedict XIV). Canon of the Cathedral of Bologna. Canon of the Liberian Basilica. Maestro di Camera of Benedict XIV (1743). Archbishop of Bologna (1754-1775). Clement XIV made him pro-Datary, on the death of Cardinal Cavalchini in 1774. Died December 3, 1775, and buried in the Cathedral in Bologna.

- Clemente Argenvilliers (aged 70) [Romanus]; his father had been a valet de chambre for the Salviati. Cardinal Priest of Sma. Trinità al Monte Pincio (1753-1758), Prefect of the S.C. of the Tridentine Council. He was a lawyer, made a Consistorial Advocate by Clement XII. Died December 23, 1758. He was buried in his titulus, Santissima Trinità [V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma III, p. 165 no. 429]. A memorial inscription in S. Giovanni Laterano, where he was a Canon: V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma VIII, p. 89 no. 242].

- Antonio Andrea Galli, Canon Regular of the Cong. Sanctissimi Salvatoris de Reno (aged 60) [Bononiensis], Cardinal Priest of S. Pietro in Vincoli (1757-1767). Doctor of Theology (Bologna). Abbot of the Monastery of S. Cecilia di Corbara (diocese of Bologna), but also Lector in theology at the Monastery of S. Pietro in Vincoli in Rome. Consultor of the SC of the Index. Qualificator of the SC of the Inquisition and of the SC of the Examination of Bishops. Procurator General of the CRSS (1748). General of his Order (1750-1753). Named a cardinal on November 26, 1753. Major Penitentiary (1755-1767), on the death of Cardinal Besozzi. Prefect of the SC of the Index. Protector of the Greek College in Rome. Died in Rome on March 24, 1767, at the age of 69, and was buried in his titulus of S. Pietro [V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma VIII, p. 93, no. 214].

- Antonio Sersale (aged 55) [Sorrento], Cardinal Priest of S. Pudenziana (1754-1775). Archbishop of Naples (1754-1775). Died June 24, 1775.

-

Alberico Archinto (aged 59) [Mediolanensis], nephew of Cardinal Girolamo Archinto (1776-1799). Doctorate (Pavia). Accompanied his uncle on the Legation to Cologne, and then to Poland. Named Protonotary Apostolic by Clement XII. Vice-Legate of Bologna. In 1739 he was appointed Nuncio to Florence, and consequently named titular Archbishop of Nicaea in Ottoman Turkey (1739-1756). Nuncio in Poland (1746-1752). Governor of the City of Rome. Cardinal Priest of S. Lorenzo in Damaso (1756-1758). Vice-Chancellor S.R.E. (1756-1758). Secretary a secretis to Benedict XIV and Clement XIII. Died September 30, 1758, and buried in S. Lorenzo in Damaso [V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma V, p. 212 no. 607]. The Duc de Choiseul thought that he would be good for the post of Secretary of State [Boutry, Choiseul à Rome, p. 240].

-

Giovanni Battista Rovero (Roëro) da Pralormo (aged 73) [His family had a feudal holding at Pralormo in Asti], Cardinal Priest without titulus (1756-1758), He received the titulus of S. Crisogono on August 2, 1758. He had studied in Turin, Rome, and Pisa, which granted him a Doctorate in Civil Law. Back in Turin, he was granted a Canonate in the Cathedral, and presently was advanced to the Archdeaconate. Victor Amadeus, King of Sardinia, named him Bishop of Acqui (1727-1744). He was consecrated by Benedict XIII personally. In 1744, he was promoted by Benedict XIV to the Archbishopric of Turin, and King Victor Amadeus bestowed on him the Abbey of S. Maria di Casanova. He received the cardinal's hat from Benedict XIV on April 5, 1756. Archbishop of Turin (1744-1766). He died in Turin on October 9, 1766, at the age of 80, and was buried there in the Church of the Discalced Carmelites.

-

Paul d'Albert de Luynes (aged 55) [Versailles], son of Honore-Charles, Duc de Montfort, and Marie-Anne-Jeanne de Courcillon. Doctor of theology (Bourges). Vicar-General of the diocese of Meaux. Bishop of Bayeux (1729-1753). Grand Aumonier of the Dauphin, 1746. Archbishop of Sens (1753-1788). Cardinal Priest without titulus (1756-1758). He received the titulus of S. Tommaso in Parione on August 2, 1758 (1758-1788).

- Etienne-René Potier de Gesvres (aged 61) [Paris], nephew of Cardinal Léon Potier de Gesvres. Bishop of Bourges (1694-1729). Vicar-general of Bourges. Bishop of Beauvais (1728-1772). Cardinal Priest without titulus (1756-1758), He received the titulus of S. Agnese fuori le mura on August 2, 1758 (1758-1774). He died on July 24, 1774.

-

Franz Konrad Casimir von Rodt-Busmanshausen (aged 52) [Marienburg]. Canon of the Cathedral of August (1726). Dean of the Cathedral (1741). Appointed Provost of Konstanz by Benedict XIV in 1744. He was elected to succeed his uncle, Casimir Anton von Sickingen (1743-1750), in the bishopric. Bishop of Konstanz (1751-1775). Cardinal Priest without titulus (1756-1758), on the nomination of Empress Maria Theresa. He received the titulus of S. Maria del Popolo on August 2, 1758 (1758-1775). He died on October 16, 1775. He arrived in Rome on Tuesday, June 27, 1758, and entered Conclave on June 29.

- Alessando Albani (aged 65) [Romanus], Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Via Lata (died December 11, 1779). Co-Protector of the Empire.

- Neri Maria Corsini (aged 73) [Florentinus], uncle of the Duke Corsini. Cardinal Deacon of S. Eustachio (died December 6, 1770). Archpriest of the Lateran Basilica, Secretary of the Holy Office. Nephew of Clement XII.

- Agapito Mosca (aged 80) [Pisaurum], Cardinal Deacon of S. Agata alla Suburra (1743-1760). consanguineus of Clement XI. Died August 21, 1760, at the age of 82. Buried in the Church of the Capucines [G. Frascarelli, Inscrizioni picene che esistono in diversi luoghi di Roma (Roma 1868), p. 145].

-

Girolamo Colonna di Sciarra (aged 50) [Romanus], son of the 4th Prince of Carbognano, brother of the Prince of Palestrina, and of Cardinal Prospero Colonna di Sciarra. Cardinal Deacon of Ss. Cosma e Damiano (1756-1760), previously Cardinal Deacon of S. Angelo in Pescheria (1743–1753). Protonotary and Maggiordomo del Palazzo Apostolico (1732), Governor of the Conclave of 1740; and, as cardinal, Pro-Maggiordomo of the Apostolic Palace. Vice-Chancellor S.R.E. (1753-1756). Camerlengo of the Holy Roman Church (1756-1763). Archpriest of the Liberian Basilica (1745-1763). Protector of all the Franciscans. He died on January 18, 1763, and was buried in the Lateran Basilica in the Colonna vault. He was hostile to French interests.

- Prospero Colonna di Sciarra.(aged 51) [Romanus], Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria ad Martyres (1756-1763), previously Cardinal Deacon of S. Giorgio in Velabro (1743–1756). Maestro di Camera di SS. He died April 20, 1765, and was buried in the Liberian Basilica. The more active of the two Colonna.

-

Domenico Orsini d'Aragona. (aged 38) [Romanus-Neapolitanus], son of Ferdinando Bernualdo Filippo, 14th Duca di Gravina, and Donna Giacinta Marescotti Ruspoli, daughter of Don Francesco, Principe di Cerveteri. Domenico was the fifteenth Duke of Gravina. He married Principessa Donna Anna Paola Flaminia Odescalchi, daughter of Principe Don Baldassarre, Duca di Bracciano, in 1738 (died 1742). They had two sons and two daughters. Cardinal Deacon of S. Nicola in Carcere (died January 19, 1789).

- Giovanni Francesco Albani (aged 38), Cardinal Deacon of S. Cesareo in Palatio (died September 15, 1803).

- Flavio Chigi (aged 46) [Romanus], Cardinal Deacon of S. Angelo in Pescheria (1753-1759). His family were opposed to the French. He was part of the Albani faction due to family connections. Died July 12, 1771.

- Giovanni Francesco Banchieri (aged 63) [Pistoria], brother of Cardinal Oddi's sister-in-law. Cardinal Deacon of S. Adriano al Foro (1753-1763). Legate in Ferrara. Died October 18, 1763.

-

Luigi Maria Torregiani (aged 60) [Florentinus], Cardinal-Deacon of Ss. Vito, Modesto e Crescenzia (1754-1765). Legist. Governor of some minor Italian towns in the Papal States. Benedict XIII (1724-1730) made him one of the Ponenti di Consulta. In 1724, he was Governor of Citta di Castello. In 1738, Clement XII made him Secretary of the SC on Immunities (a congregation founded on June 22, 1622, by Urban VIII, taking over tasks previously dealt with by the SC on Bishops (founded by Sixtus V on January 22, 1588). In 1743, Benedict XIV placed him on the SC de Consulta. He was promoted to the Cardinalate on November 26, 1743, and made Protector of the Franciscans, the Reformed Franciscans, the Third Order of S. Francis, the monks of Mount Olivet and of Monte Vergine. He was named Secretary of State by the new Pope, Clement XIII (Rezzonico). Pius VI made him Secretary of the Holy Roman Inquisition. He died on January 6, 1777, and was buried in S. Giovanni dei Fiorentini. The Duc de Choiseul thought that he had considerable talent for the administration of the internal affairs of the Church, but that he knew nothing about foreign affairs [Boutry, Choiseul à Rome, p. 244]

- Thomas Philip Wallrad d'Hénin-Liétard d'Alsace-Boussu de Chimay (aged 78) [Bruxelles], Cardinal Priest of S. Lorenzo in Lucina (1752-1759). Archbishop of Mechlin (1715-1759). Died January 5, 1759.

-

Joseph Dominicus von Lamberg (aged 77) [Styria, Austria], nephew of Cardinal Johann Philipp von Lamberg, Bishop of Passau (1689-1712). He studied at Besançon in Burgundy, in Siena, and in Rome at the Collegio Clementino. He was elected a Canon in his uncle's Cathedral in Passau in 1703, and in 1705 he was elected Provost. He was also named a Canon in the Cathedral of Salzburg. Pope Clement XI appointed him Bishop of Seckau (Graz) in Styria (1712-1723), and then in 1723 he was appointed Bishop of Passau (1723-1761). On the recommendation of the Emperor Charles VI, he was named Cardinal Priest of S. Pietro in Montorio, created on December 20, 1737. He died on August 30, 1761, and was buried in the Cathedral of SS. Stephanus et Laurentius in Passau. Neither the names of his conclavists nor the name of his dapifer appear on the grants of privileges from the Conclave of 1758. He was not present, despite the statement of Cardella that he was.

- Johannes Theodor von Bayern (aged 54), Cardinal Priest of S. Lorenzo in Panisperna (died January 27, 1763). Bishop of Liège (1744-1763).

- Álvaro de Mendoza (aged 86), Cardinal Priest without titulus (died January 23, 1761). Patriarch of the West Indies.

- Giovanni Battista Mesmer (aged 87), born in Milan on April 21, 1671. Cardinal Priest of S. Onofrio (died June 20, 1760). Cleric of the Apostolic Camera, Prefect of the Annona (1724). Did not enter the Conclave due to age and illness. According to Novaes [Elementi XV, 5], "... Cardinale Mesmer, che non vi entrò mai, a cagione della sua decrepita età di anni 87., per cui si reso affatto imbecille."

- José Manuel da Camara d'Atalaia (aged 71), Cardinal Priest without titulus (died July 9, 1758). Patriarch of Lisbon (1754-1758).

- Luis Fernández de Córdoba (aged 62), Cardinal Priest without titulus (1754-1771). Archbishop of Toledo (1755-1771). Died March 26, 1771.

-

Nicholas de Saulx-Tavannes (aged 67) [Paris], of Charles-Marie, Marquis di Tavannes; and Marie-Catherine d'Aguesseau. Cardinal Priest without titulus (1756-1759). Archbishop of Rouen (1733-1759) [Gallia christiana 11, 115]. Doctorate (Sorbonne), 1716. Vicar-General of the Archbishop of Rouen. Bishop of Chalons in 1721 on appointment of Innocent XIII; consecrated at the church of the Theatines in Paris by Cardinal André-Hercule de Fleury [Gallia christiana 9, 901-902]. In 1733, Clement XIII made him Archbishop of Rouen. He was named Grand Aumonier to the Queen of France, and invested with the Commandership of the Order of the Holy Sprit by Louis XV in 1747. Provisor of the Sorbonne. Died March 10, 1759.

- Francisco de Solís Folch de Cardona (aged 45) [Madrid], son of José Solís y Gante, Marquis of Castelnovo, Count of Saldueña and third Duke of Montellano; and Josefa Folch de Cardona, fifth Marquesa de Castelnovo y Pons. Cardinal Priest without titulus (1756-1769); his red biretta was brought to Spain by the Conte de Madauli, and presented on June 27, 1756. Titular Bishop of Trajanopolis (March 16, 1749), in order to be coadministrator of the Bishopric of Cordoba, which was held by the Infante Don Luis. Bishop of Cordoba (1752-1755). Archbishop of Seville (1755-1775). He did attend the Conclaves of 1769 and 1774; the anti-Jesuit campaign of the Bourbons insisted on a full Spanish presence. Died March 21, 1775. Unusually, Pope Pius VI attended his funeral, along with thirty cardinals, with the Requiem Mass being sung by Cardinal Calini. The Pope gave the final absolution. The body was transferred to Seville, where it was buried on April 12, 1775 [Castellanos de Losada, Biografia eclesiastica completa 27 (Madrid 1867), 808-809].

-

Francisco de Saldanha da Gama (aged 35), son of John, Viceroy of India. Doctor of Canon Law. Cardinal Deacon with no deaconry (1756-1759), on the nomination of King Joseph I of Portugal; subsequently Cardinal Priest without titulus (1759–1776). He conducted the investigation of the activities of the Jesuits in Portugal, the Algarves, and the Two Indies, with papal faculties from Benedict XIV (In specula supremae: April 1, 1758), granted at the request of the Marques de Pombal [Biker (editor), Collecção dos Negocios de Roma no Reinado de El-Rey Dom José I. Parte I (Lisboa 1874), pp. 48-52]. In thanks for his cooperation, he was made Patriarch of Lisbon (1759–1776), at the instigation of Pombal. Died as Patriarch of Lisbon on November 1, 1776, never having visited Rome.

Points of View

In a letter of May 6, 1758, the Neapolitan Minister of Carlos III, Marchese Bernardo Tanucci, wrote his instructions for Cardinal Domenico Orsini da Gravina. The date of his letter suggests that the Neapolitans, at least, had been thinking in advance about the possible candidates for the Papacy. King Charles III of Naples was the brother of Duke Philip of Parma. France had secretly promised the Duchy of Milan to the Duke of Parma, but at the conclusion of the War of the Austrian Succession the Austrians negotiated a treaty that returned the situation in Italy to the status quo ante. France had acquiesced in this, and Austria remained in possession of Milan and Tuscany. The Duke of Parma had been deceived. The Bourbons and the Hapsburgs were face to face in northern Italy, as they had been in the War of the Spanish Succession. Tanucci wrote that [Petruccelli IV, 142] he wanted a "friend" of Naples, he would content himself with "an indifferent", but, with God's help and human force, he wanted to avoid an enemy. Considering the states with which Naples might come into some conflict, Piedmont and Austria, he wanted to choose from subjects of the Papal States. He named Sacripanti, Crescenzio, the two Colonnas, and Borghese. He rejected Oddi (of Perugia, bought by the Austrians), Masca, Passionei (who had been Nuncio in Vienna for nine years), Paolucci, Imperiali (who was Genoese), and certainly Spinelli (who had been made to leave the archbishopric of Naples because he had wanted to introduce the Inquisition). Orsini was advised to work with France and Spain (Bourbon monarchies), with Poland, with Cardinal de la Rochefoucald and Msgr. Clementi (the Neapolitan agent in Rome). Earlier, in a letter of January 8, 1757, Tanucci had written to the Conde de Cantillana that "Spinelli era un hombre inquieto, intrigante, vengativo, amigo de novedades y enemigo de los jesuitas, y por consecuencia poco apto para apaciguar la masa del pueblo francés." [In general, see Manuel Danvilla y Collado, Reinado di Carlos III Tomo I (Madrid 1893), 302-312 and 351-372; the letter is quoted at 302-303]. Orsini and Portocarrero decided to form a bloc sufficient to impose a virtual exclusiva, and Orsini revealed to him that he carried the Neapolitan veto of Spinelli [Petruccelli IV, 149]. Naples, of course, did not have the formal right of veto; that belonged only to France, Spain, and the Empire.

The Florentine cardinals were the subject of much suspicion in several quarters, seeing that they were subjects of the Austrians. Cardinal Bardi in particular was disliked by the Bourbon monarchies as a friend of the Jesuits. Cardinal Corsini, Bardi's cousin was a nepotist, actually had a nephew, and was soliciting a cardinalate for him. Both Bardi and Corsini were thought, even by the Austrians, to be too attached to the interests of Florence above any other. Tempi was a faithful subject of Austria, and not particularly competent. The rest were D'Elci, the Dean of the College of Cardinals, Guadagni, Feroni, Banchieri and Torregiani—a total of eight. Corsini himself was said to be pushing Sacripanti, his cousin Bardi, Imperiali, and the Dean Cardinal D'Elci. If the claim with respect to D'Elci is true, it can have been no more than a maneuver to bring time, during a short and inactive papacy, to retrench and lay plans.

The creature of Benedict XIV (Lambertini) formed a group of some twenty-three members, who were under pressure from various groups to which they also belonged by origin, by past work, or by financial considerations. Pope Benedict had not been a nepotist, and so there was no Cardinal Nephew to claim leadership.

The French had a serious problem, which the Duc de Choiseul pointed out in a memorandum of April, 1757 [Boutry, Choiseul à Rome, p. 260]. The French Ambassador in Rome, the Cardinal de Rochefoucault, had died on April 28, 1757. Who would have the authority necessary to replace him in the Sacred College if it came to a Conclave? Two French cardinals who could go to Rome were Cardinal Paul de Luynes and Cardinal Etienne-René Potier de Gesvres, but neither spoke Italian, and neither was acquainted with the customs and habits of the Court of Rome. They would be easy targets for the many intriguers who frequent a Conclave. And they would have trouble presenting French points-of-view in acceptable and convincing ways. The analysis is filled with a good dose of chauvinism; Versailles was no less filled with intrigue than Rome. Choiseul nonetheless recommended that the French Court find an Italian cardinal, who could manage the French cardinals as well as the King's affairs—a Protector. There had been no French Protector since the death of Cardinal Ottoboni during the Conclave of 1740. Choiseul suggested Spinelli, Lanti (who had solicited the position from Choiseul), and Sciarra Colonna. This matter had to be decided upon quickly, so that the appropriate Italian cardinal could be approached before a Conclave was in sight. Choiseul's successor as Ambassador in Rome was Msgr. Jean-Francois-Joseph de Rochechouart, Bishop of Laon. In a third memorandum, also of April, 1757 [Boutry, Choiseul à Rome, p. 266; cf. 235-236], Choiseul reminded the King that Paolucci, Mosca, and Sacripanti should be subject to exclusion. Also, France should work against D'Elci, Cavalchini, and Mattei, as more bad than good.

Conclave

On Monday, May 15, the day after Pentecost, the Mass of the Holy Spirit was celebrated by the Dean of the Sacred College, Rainiero D'Elci. The Oratio pro pontifice eligendo was pronounced by Msgr. Giovanni Battista Bortoli, a Venetian, titular Archbishop of Nazianzus. The Conclave opened with only twenty-seven cardinals present, less than fifty percent of the total number, it was impossible as yet to proceed to a convincing election.

In the First Scrutiny, on May 16, Cardinal D'Elci received eleven votes. This was only a demonstration of strength on the part of Corsini. D'Elci was not his first choice, and at the age of 88, he could not have had a long or active pontificate. Corsini's real candidate was Spinelli, which caused shudders between Portocarrero and Orsini. Spinelli was alienated from Naples and France, and was calling himself one of the Zelanti. However, as consultations began, Portocarrero Mendoza (Cardinal Bishop of Sabina), and Domenico Orsini d' Aragona (nephew of Benedict XIII) in fact undertook to promote the candidacy of Cardinal Carlo Alberto Cavalchini (the Prefect of the Sacred Congregation of Bishops and Regulars). This did not, to be sure, mean that Cavalchini was their ultimate and best candidate, only the one to be first in the brutal examination of the Scrutinies. How useful, though, if it could induce France or the Emperor to interpose their one and only veto. Corsini begged Orsini not to get a veto against Spinelli, and Orsini agreed to engage in consultations with the various Courts; Corsini too sent of letters to the various Courts, attempting to present a positive view of Spinelli. Orsini knew that if he were to have to veto Spinelli, the veto would have to be interposed by Portocarrero on behalf of the Spanish, and Orsini was not certain he could count on that. Better to make it obvious to Spinelli that he could not win, and have him cease his candidacy on his own.

Corsini must have understood the message. On the evening of May 17, Corsini suddenly began canvassing for Tamburini, a seventy-five year old Benedictine monk of the Cassenien congregation (not a monk of Monte Cassino), whose uncle had been General of the Jesuits. The intention, again, must have been to provoke Spain or France into using their formal veto. It failed, and Tamburini disappeared from the lists. Tamburini, however, remained hopeful, and made his services available to the designs of Orsini and Portocarrero (the agents of the Borbon monarchs). This, in fact, gave them one more vote for Cavalchini. Eventually, they were able to assemble a group of nineteen cardinals. But all of this was mere maneuvering. The French Ambassador, Msgr. Jean-Francois de Rochechouart, Duke-Bishop of Laon (1741-1777) [Gallia christiana IX, 559], insisted that the Cardinals wait for the arrival of the French cardinals, and Cardinal Albani likewise insisted that they wait for the arrival of Cardinal von Rodt, who would be bringing the Instructions of the Emperor Franz and Empress Maria Theresa. His Instructions were not even signed in Vienna until May 22, 1758.

On May 21, 1758, during the Sede Vacante, the XVI General Congregation of the Jesuits was also meeting in their own conclave. The previous General, Fr. Luigi Centurioni, had died on October 2, 1757, and the General Congregation began meeting on May 8, 1758 to elect his successor. They chose as their new Procurator General Fr. Lorenzo Ricci, SJ. Ricci, a Florentine, was 55 years old. His brother was First-Syndic of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany.

On June 2, 1758, the Imperial Court in Vienna issued instructions for Cardinal Albani and Marchese Clerici.

On June 3, the Count of Rivera wrote to the King of Sardinia that he thought that the Imperial candidate was Cardinal Archinto of Milan, the Vice-Chancellor [Petruccelli IV, 151-152, in his French translation]:

Les cardinaux des Légations et de l' Italie commencent à arriver et la besogne chauffe. J'ai des raisons pour douter qu' Albani veuille sincèrement Mosca; je le crois plus enclin pour Oddi. On a découvert une négociation solide en faveur d' Archinto, qui est le candidat de Vienne. Cette cour a préféré, en vue de celà, de nommer son ambassadeur extraordinaire auprès du conclave le marquis Clerici, neveu d' Archinto. L' opposition de la France cesse à cause des bonnes relations qui existent maintenant entre Vienne et Versailles. Sollicitée, la France accède à cette nomination, d'autant plus qu' Archinto serait ce pape souple—maneggievole—qui demandait Rohan. Pour plier la France, on a fait agir la princesse Trivulzi, la duchesse infante de Parme, laquelle fait prendre à Son Éminence [Archinto] l' abbé Lascari [Alessandro Lascaris dei Conti di Ventimille] pour dapifère, malgré les instances des plus distinguées familles de France; car cette place est ambitionnée à cause du privilege dont elle jouit, d' exempter des lourdes dépenses que l' investiture des bénéfices et des évêchés occasionne.

La France et l' Autriche étant d' accord, Portocarrero ne peut pas s' abstenir. Il ne s' agit maintenant que d' embaucher les électeurs. Pour cela, des manéges à ne pas finir. Les jeunes ne reculent pas; Torregiani se précipite, dans l' espoir de la secrétairerie d' Etat, ainsi que Feroni dans celui de la chancellerie. Corsini est attiré par les pratiques faites auprès de la maison Bracciano, et surtout auprès de donna Maria-Anna Cenci. Archinto est un des candidats de Spinelli, bien qu' il préfère Imperiali. Avec tout cela, qui est cependant bien joli, Archinto s' évanouira: il a contre lui les vieillards; et sans les vieux, point de pape. Puis des neveux à foison. L' anxiété de Venise pour le nouveau pape est très-grande. Outre de Rezzonico, la République a obligé le décrépit Delfino à se mettre en voyage.

Rivera's character had been noted by the ex-Ambassador of France in Rome, the Duke de Choiseul. In April of 1757 he wrote to the King of France [Boutry, Choiseul à Rome, p. 311],

Le comte de Rivera, ministre plénipotentiaire de Sardaigne, a de l' esprit et beaucoup de feu, mais il a le malheur d' être sourd absolument, de sorte qu'il est impossible de lui parler. Comme il est léger en propos, quelquefois il en tient de hasardés. Il met assez indiscrètement la Cour de Turin au-dessus de toute l'Europe, mais, à ce ridicule, il joint de la gaieté, des connaissances, et je me suis fort bien accommodé de lui.

On June 10, Cardinal Albani announced the imminent arrival of Cardinal von Rodt, with the Instructions of the Court of Vienna. But on the 17th, according to Rivera, von Rodt was not yet in the Conclave.

The results of the balloting on June 19 showed that Cardinal Cavalchini had obtained 21 votes. This made his election a serious possibility. On the 21st, his total had risen to twenty-six [Wahrmund 229; Montor says twenty-three; Novaes says thirty-three cardinals were prepared to vote for him, which is certainly wrong, as that would have made him pope]. On that same evening, Cardinal de Luynes, acting on instructions from the French government, presented to Cardinal d'Elci, the Dean of the Sacred College, the veto (exclusiva) against Cardinal Cavalchini; it is said that the reason was that Cavalchini was favorable to the Jesuits and had voted for the canonization of Robert Cardinal Bellarmine, SJ [Ravignan, 30].

On June 24, Cardinal Bardi and his conclavists exited the Conclave for reasons of health [Diario ordinario, 1 Luglio, 1758, p. 9]

Cardinal von Rodt finally appeared in the Conclave on June 29 [Petruccelli IV, 153, 158; the date given by Wahrmund, June 26, is not correct]. Up until that point, Cardinal Albani had been handling the Imperial faction alone, and working to keep together enough votes to provide a virtual exclusiva if necessary. His instructions contained remarks favorable to Cardinals Borghese, Cavalchino, Oddi, Lante, Stopani and Doria, and he was authorized to use a veto if necessary, especially against a French cardinal. Somewhere he had a list of seventeen cardinals who were acceptable to Vienna. At that point there were forty-five cardinals in the Conclave. Von Rodt's arrival had thoroughly stirred the pot, and negotiations began again. But it was the height of the Roman summer, and tempers were rising with the temperature and humidity.

Election of Cardinal Rezzonico

It was apparently Cardinal von Rodt who, along with some of his associates, decided to put forth the name of Cardinal Rezzonico [Novaes XV, 6]. In the balloting on July 4 Rezzonico received 22 votes. On that same day Cardinal Girolamo de' Bardi was carried out of the conclave; he had been struck with illness two days earlier [Diario di Roma, 9].

On the afternoon of Thursday, the 6th of July, 1758, Rezzonico received thirty-one votes out of forty-three cast, which brought him canonical election. He chose the name Clement XIII. The Conclave had lasted 53 days, the Sede Vacante had lasted 65 days. His election was proclaimed to the people from the main exterior balcony of the Vatican Basilica at 22.45 hours by Cardinal Alessandro Albani, the prior diaconum. At 23.00 hours, the new pope returned to the Sistine Chapel, vested in gold mitre and red cope, and seated himself upon the altar for the Second Adoration. When that was concluded, the Pope was escorted to S. Peter's Basilica, where the Third Adoration took place. The procession was led by Prince Colonna, the Governor of Rome, the Duke of Guadagnuolo, master of the Sacred Hospice; and the Ambassador of Bologna.

.jpg) The Venetian Cardinal Carlo della Torre Rezzonico, Bishop of Padua, was crowned at St. Peter's on July 16, 1758, and he took solemn possession of the Lateran Basilica on November 13.

The Venetian Cardinal Carlo della Torre Rezzonico, Bishop of Padua, was crowned at St. Peter's on July 16, 1758, and he took solemn possession of the Lateran Basilica on November 13.

Cardinal Archinto was appointed Secretary of State; he died however on September 30. He was succeeded by Cardinal Luigi Maria Torrigiani, one of the most committed of the supporters of the Jesuits. Cardinal Calvachini was appointed pro-Datary, and Monsignor Carlo Rezzonico, nephew of the Pope, was appointed Secretary of Memorials.

On April 20, 1759, Pombal caused Joseph I of Portugal to send a letter to the Pope, announcing his intention to expel the Jesuits from Portugese territories.

Bibliography

Relazione di Rome intorno all' Elezione del sommo pontefice Clemente XIII. Seguita li 6. Luglio 1758. (Roma 1758) Seconda relazione. De' 15. Luglio 1758. Terza relazione. De' 22. Luglio 1758.

Brevi e distinte Notizie dell' esaltazione al pontificato di Sua Santita Clemente XIII. Rezzonico Veneziano (Venezia: Benedetto Milocco 1758).

Diario ordinario (Roma: Chracas 1758).

Geheime und zuverlassige Geschichte von dem Konklave und der Wahl der sechs leztern Papste, als Benedikt XIII. Klemens XII. Benedikt XIV. Klemens XIII. Klemens XIV. und Pius des VIten (Mit Sonnleithnerischen Schriften, 1782), 23-28.

Giuseppe Novaes, Elementi della storia de' sommi pontefice terza edizione Volume 14 (Roma 1822) 244-246 [death of Benedict XIV]; Volume 15 (Roma 1822), 1-7 [Election of Clement XIII (Rezzonico)].

[Continuators of B. Platina], Vita di Clemente XIII pontefice massimo (Venezia: Domenico Ferrarin 1769), 5-7; 16. Alexis François Artaud de Montor, Histoire des souverain pontifes romains VII (Paris 1851) 116-119. Xavier de Ravignan, SJ, Clement XIII et Clement XIV 2 volumes (Paris 1854). G. P. Grimani, Sull' elezione del card. Carlo Rezzonico... (Padova 1875) Ludwig Wahrmund, Ausschliessungs-recht (jus exclusivae) (Wien 1888) 228-229.

Geheime und zuverlassige Geschichte von dem Konklave und der Wahl der sechs leztern Pabste, als: Benedikt XIII. Clemens XII. Benedikt XIV. Clemens XIII. Clemens XIV. und Pius des VIten (Mit Sonnleithnerischen Schriften 1782). Andrea Moschetti, Venezia e l' elezione di Clemente XIII (Venezia: Vicentini 1890).

Maurice Boutry, Choiseul à Rome, 1754-1757 (Paris: Calmann Lévy 1895) ['Mémoire sur le conclave' (November 19, 1756), pp. 221-255 ; 'Deuxième mémoire' (April 1757), pp. 256-266; 'Troisième mémoire' (April 1757), pp. 266-312].

D. Gravino, Per la storia del conclave di Clemente XIII (1758) (Genova: Sordimuti 1898).

Pietro Luigi Galletti, OSBCassin., Memorie per servire alla storia della vita del Cardinale Domenico Passionei, Segretario dei Brevi e Bibliotecario della S. Sede Apostolica (Roma: Generoso Salamoni 1762).

Carini, Isidoro, L' Arcadia dal 1690 al 1890. Memorie storiche 2 volumes (Roma 1891). Crescimbeni, Giovanni Mario, Le vite degli Arcadi illustri Prima parte (Roma: Antonio de Rossi 1708); Parte Seconda (1710); Parte Terza (1714); Parte Quarta (1727); Parte Quinta (1750).