SEDE VACANTE 1669-1670

December 9, 1669—April 29, 1670

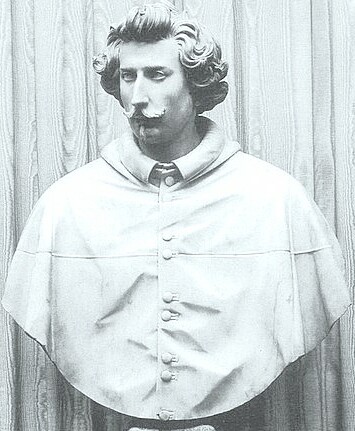

Antonio Cardinal Barberini

Pietro Cardinal Vidoni Flavio Cardinal Chigi Leopoldo Cardinal de Medici

ANTONIO CARDINAL BARBERINI, iuniore (1607-1671), the Cardinal Camerlengo, was the son of Carlo Barberini and Costanza Magalotti. He was the nephew of Pope Urban VIII (Maffeo Barberini, 1623-1644), of the Capuchin Antonio Card. Barberini, seniore, (1624), and of Lorenzo Card. Magalotti. His brother Francesco became Cardinal on the election of their uncle to the papacy, and his brother Taddeo became Prince of Palestrina and Prefect of Rome. He was the cousin of Francesco Maria Card. Machiavelli (who became cardinal in 1641), and uncle of Carlo Card. Barberini (1653), who deputized as Camerlengo for his uncle, who was present but ill (Antonio left the conclave on February 3 and only returned on March 17), at the conclave of 1669-7. Antonio Barberini was Grand Prior in Rome of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem.

The accession of his uncle brought Antonio Barberini and his brothers many positions of power, wealth and influence. He became Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Aquiro in 1627, and Camerlengo of the Holy Roman Church on July 28, 1638, a position which he held until his death on August 3, 1671. In that capacity he presided over the Conclaves of 1644, 1655, 1667 and 1669-1670. The authoritarianism, arrogance and greed of the family ("Quod non fecerunt Barbari, fecerunt Barberini.") brought a strong reaction on the death of Urban VIII. In 1645 Antonio and Taddeo fled to Paris (where Urban VIII had once been ambassador), and remained in exile at the Court of Louis XIV (under the patronage of the Sicilian Giulio Card. Mazzarini) until 1653; he became Grand Almoner of France and a member of the Order of the Holy Spirit. In 1657 he was nominated Archbishop of Rheims, a choice which was approved by Pope Alexander VII. He became Cardinal Bishop of Palestrina in 1661. He died in Rome on August 3, 1671.

Cardinal Barberini was Cardinal Camerlengo during the conclaves of 1644, 1655, 1667 and 1670.

|

AG •ROMA• |

|

|

Cardinal Francesco Barberini was Dean of the Sacred College of Cardinals.

The Governor of the Conclave was Msgr. Camillo Massimi (1620-1677), the titular Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem. He had been Nuncio in Spain from 1654 to 1656, but had caused a diplomatic uproar which required his recall. He was unemployed thereafter. The College of Cardinals elected him Governor of the Conclave of 1670. He was immediately named Maestro di Camera by the new pope, and on December 21, 1670, he was named cardinal, with the title of Cardinal Priest of S. Maria in Domnica, which he exchanged for S. Eusebio in 1673, and S. Anastasia in 1676. He took part in the conclave of 1676 (Novaes, p. 212).

The Prefect of the Apostolic Palace, and one of the external custodians of the Conclave was Msgr. Bernardino Baccio, titular Latin Archbishop of Damascus.

The Marshal of the Conclave was Prince Giulio Savelli (1626-1712) [Gattico I, 360], the second son of Prince Bernardino Savelli, Prince of Albano (1606-1658) and Felice Peretti, the heiress of Pope Sixtus V. He married Caterina Aldobrandini, daughter of Pietro Aldobrandini, Duke of Carpentino, and then Caterina Giustiniani. The family were perpetually in financial difficulties: in 1596 they sold Castel Gandolfo to the pope, and in 1650 the duchy of Albano. He succeeded his father as Marshal of the Holy Roman Church in 1658. He had one son, who predeceased him. On his death in 1712, the office of Hereditary Marshal of the Roman Church was conferred on the Chigi Family. Prince Giulio Savellio left a manuscript Conclave Diary, Index generalis omnium instrumentorum et actorum Sedibus Vacantibus Marescalli Sedis Apostolicae; it is in the Chigi archives [de Bildt, vi-vii].

The Secretary of the Sacred College of Cardinals was Abbe Franciscus Polinus, basilicae Lateranensis canonicus.

The Ceremoniere were

Franciscus Pheobeus, Archbishop of Tarsus, primus ceremoniarum magister

Carlo Vincenzio Carcarasio, Canon of St. Peter's

Fulvio Servantio, Canon of S. Maria in Via lata.

Petrus Antonius della Pedacchia, perpetuus beneficiatus of St. Peter's

Pietro Paolo Bona.

Death of Clement IX

Pope Clement IX (Rospigliosi) was ill throughout the autumn of 1669 with hernia and kidney stones. Nonetheless, in his anxiety over the Turkish advance in Crete, he undertook a pilgrimage to the seven basilicas in Rome. The next evening the Pope had a serious attack that left him senseless; it was diagnosed as 'apoplexy'. On November 29, ten days before he died, he named seven new cardinals and announced the name of one who had been held in pectore (Luis Portocarrero). Thirty-four cardinals attended the Consistory. Clement's purpose was to create a 'faction' for his nephew, Cardinal Giacomo Rispogliosi, to defend the principles which had governed Clement's reign. During this Consistory he addressed some remarks to his cardinals on the election of his successor [Louis XIV to the Duke de Chaulnes, December 22, 1669: Hanotaux (editor), Recueil, 228]. This was his last public act; he had no strength to hold the public consistory to award the red hats or assign the names of the cardinalatial titles. He finally died of a stroke, perhaps brought on by the stress of hearing of the defeat and expulsion of the Venetians from the island of Crete. He died at the Quirinal on December 9. [Novaes, 172-173; de Bildt, 14-15]. It is worth noting that, three days before his death, the Spanish ambassador, Astorga, wrote to the Viceroy of Spain, Don Pedro de Aragona, that the factions might coalesce around Cardinal Altieri [de Bildt, 57].

Two hours after sunset, a procession conveyed the body of the deceased pope from the Quirinal Palace to the Vatican. On December 12, the body was interred temporarily.

As soon as he heard the news of the creation of new cardinals and the Pope's illness, Louis XIV ordered Cardinals Grimaldi, de Retz, and de Bouillon to get to Rome without delay. They were to join with the other cardinals of the French faction: d'Este, Antonio Barberini, Orsini, Maidalchini and Mancini. Their association with the "old cardinals" of the Barberini faction, would make them a formidable force. The Duc de Chaulnes was appointed Ambassador Extraordinaire. He had, as Louis stated, given glorious proof in the preceding Conclave of his many talents. The French contingent arrived in Rome on January 16, and the Duc made his formal presentation to the College of Cardinals on January 22.

The Cardinals

There were seventy living cardinals at the death of Clement XI. A list of the participants in the Conclave is given by the Motu Proprio of the new pope, Clement X, on May 27, 1670, which granted various privileges and favors to the Conclavists of each Cardinal [Bullarium Romanum Turin edition 18 (Augusta Taurinorum 1869), iii, pp. 22-34]. It contains the names of sixty-seven cardinals

- Francesco Barberini (aged 72), Suburbicarian Bishop of Ostia and Velletri, Dean of the Sacred College of Cardinals. (died 1679)

- Marzio Ginetti (aged 84), Suburbicarian Bishop of Porto and Santa Rufina, Sub-Dean of the Sacred College of Cardinals. Vicar of Rome (1629-1671) He died at the age of 86, in 1671. His funeral inscription is in S. Andrea della Valle [ V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma VIII, p. 270 no.678].

- Antonio Barberini (aged 62), Suburbicarian Bishop of Palestrina. (died August 3, 1667). Camerlengo of the Holy Roman Church.

- Francesco Brancaccio (aged 78), Suburbicarian Bishop of Frascati (Tusculum) (died 1675).

- Ulderico Carpegna (aged 74), Suburbicarian Bishop of Albano (died 1675).

- Giulio Gabrielli (aged 66), Suburbiocarian Bishop of Sabina; formerly Cardinal Priest of S. Prisca (died 1677). Bishop of Ascoli

- Virginio Orsini (aged 55) [Romanus], son of Don Ferdinando, fourth Duca di Bracciano, Prince of the Holy Roman Empire, Signore di Trevignano, etc., Prince Assistant at the Papal Throne, Grande di Spagna di prima classe, Nobile Romano, Patrizio Napoletano, Patrizio Veneto; third Duca di San Gemini, second Principe di Scandriggia e Conte di Nerola, first Duca di Nerola; and Donna Giustiniana Orsini,daughter and heiress of Don Giovanni Antonio Orsini, first Principe di Scandriglia, second Duca di San Gemini e Conte di Nerola and Donna Costanza Savelli dei Duchi di Castel Gandolfo. Formerly Cardinal Deacon of S. Eustachio (1653-1656), Prince Virginio was currently Cardinal Priest of S. Prassede, and later Cardinal Bishop of Albano, then Cardinal Bishop of Frascati (died 1676). Protector of the Armenians and of the Kingdom of Poland. Archpriest of the Lateran Basilica [Cancellieri, Storia dei Solenni Possessi, p. 291].

- Rinaldo d'Este (aged 52) [Modena], son of Elizabeth of Savoy. Brother of the Duke of Modena. Cardinal Priest of S. Pudenziana. Formerly Cardinal Deacon of S. Nicola in Carcere (died 1672). An enemy of the Barberini since their war over Parma. But when the Spanish offended him by not sharing their councils, he went over to the French, and became their Cardinal Protector and a defender of the Barberini. In its turn, this offended Pope Innocent, and d'Este had to withdraw from Rome for a time.

- Cesare Facchinetti (aged 61), Cardinal Priest of Ss. Quattro Coronati (1643–1671). Bishop of Spoleto (1655–1672). (died 1683).

- Carlo Rosetti (aged 55), Cardinal Priest of S. Silvestro in Capite (1654-1672). Previously Cardinal Priest of S. Maria in Via (1643-1644), and of C. Cesareo (1644-1653). Titular Archbishop of Tarsus (1641-1643), Bishop of Faenza (1643-1676). Cardinal Bishop of Frascati in 1676, then Porto e Santa Rufina (1680-1681). (died 1681). He had been papal Nunzio in England in the 1630s-1640s.

- Niccolò Albergati-Ludovisi (aged 61), Cardinal Priest of S. Maria in Trastevere (1666–1676). Major Penitentiary (1650–1687). (died 1687).

- Federico Sforza (aged 56), son of Don Alessandro Sforza 1572-1631), Conte di Segni, Signore di Valmontone e Lugnano, first Duca di Segni, second Marchese di Proceno, Signore di Onano, twelfth Conte di Santa Fiora, Marchese di Varzi e Castell’Arquato e Conte di Cotignola; and Donna Eleonora Orsini, daughter of Don Paolo Giordano, first Duca di Bracciano and of Isabella de’ Medici Principessa di Toscana. Federico Sforza was Cardinal Priest of S. Pietro in Vincoli (1661–1676), formerly Cardinal Deacon of SS. Vito, Modesto e Crescenzia (1646-1656). Legate in Avignon. He succeeded Cardinal Antonio Barberini as Vice-Chamberlain S.R.E. He was Bishop of Rimini from 1646-1656 [Gauchat, p. 95]. In 1675 he became Bishop of Tivoli. (died 1700)

- Alderano Cibo (aged 67), Cardinal Priest of S. Prassede (1668–1677) Bishop of Jesi (1656–1671). (died 1700)

- Benedetto Odescalchi (aged 59), Cardinal Priest of S. Onofrio. (1659–1676). Pope Innocent XI (1676-1689)

- Lorenzo Raggi (aged 55), Cardinal Priest of SS. Quirico e Giulitta (1664–1679). Vice-Chamberlain of the Holy Roman Church (1650–1687). (died 1687).

- Jean-François-Paul de Gondi de Retz (aged 56), Cardinal Priest of S. Maria sopra Minerva (1655-1679). (died 1679).

- Luigi Omodei (aged 63), Cardinal Priest of Ss. Bonifacio ed Alessio (died 1685).

- Pietro Vito Ottoboni (aged 60), Cardinal Priest of S. Marco (1660-1667) Datary of Pope Clement IX (1667-1669). (died as Pope Alexander VIII in 1691).

- Lorenzo Imperiali (aged 58), Cardinal Priest of S. Crisogono (1654-1673). (died 1673). His funeral monument is in S. Agostino [V. Forcella Inscrizione delle chiese di Roma 5, p. 98 no. 292].

- Giberto Borromeo (aged 59), Cardinal Priest of SS. Giovanni e Paolo (1654-1672) (died 1672).

- Marcello Santacroce (aged 50), Cardinal Priest of S. Stefano al Monte Celio (1652-1674) (died 1674). Bishop of Tivoli.

- Giovanni Battista Spada (aged 72), Cardinal Priest of S. Marcello (1659-1673). (died 1675) .

- Francesco Albizzi (aged 76) [Cesena], Cardinal Priest of S. Maria in Via (1654–1671). Previously married, with several children. A lawyer. Doctor in utroque iure. Auditor of the Nunciature in Naples; Auditor of the Legation in Spain; Assessor at the Office of the Holy Roman Inquisition (1635); he was a member of Cardinal Ginetti's German legation in Vienna (1635) and in Cologne (1636-1640); he was Innocent X's Assessor in the business of the Jansenist controversy. Created Cardinal in 1654. (died 1684) .

- Ottavio Acquaviva d'Aragona (aged 60), Cardinal Priest of S. Cecilia (died 1674).

- Carlo Pio di Savoia (aged 47) [Ferrara], Cardinal Priest of S. Prisca (1667-1675). Once Treasurer General of the Apostolic Camera, then Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Domnica (died 1689, as Cardinal Bishop of Sabina).

- Carlo Gualterio (aged 56), Cardinal Priest of S. Eusebio, formerly Cardinal Deacon of S. Pancrazio. Bishop of Fermo

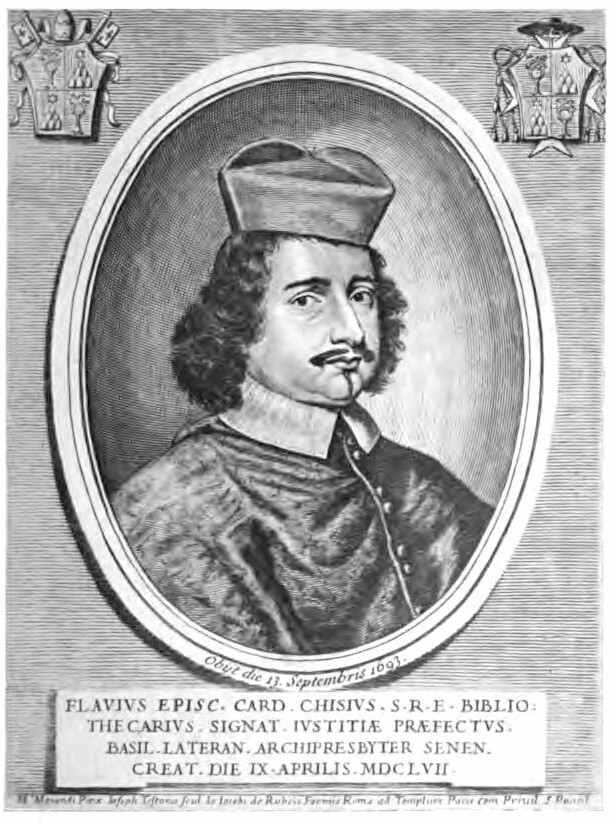

- Flavio Chigi (aged 39), Cardinal Priest of S. Maria del Popolo (1657–1686). (died 1693). Bibliothecarius Sanctae Romanae Ecclesiae (1659–1681). Archivist of the Vatican Archives. Archpriest of the Lateran Basilica (1666–1693). Nephew of Pope Alexander VII.

- Girolamo Buonvisi (aged 63), Cardinal Priest of S. Girolamo dei Schiavoni/Croati (died 1677). Bishop of Lucca (1657–1677), Legate in Ferrara.

- Scipione Pannocchieschi d'Elci (aged 70), Cardinal Priest of S. Sabina (1658–1670). Nuncio in Vienna (1652-1658). (died 1670, during the Conclave, on April 13, 1670). Former Archbishop of Pisa (1636–1663; resigned in favor of his nephew Francesco d'Elci). Favorite candidate of Cardinal Chigi.

- Antonio Bichi, (aged 56), Cardinal Priest of S. Maria degli Angeli (1667–1687). Bishop of Osimo (1656–1691). Nephew of Pope Alexander VII. (died 1691).

- Pietro Vidoni (aged 59), Cardinal Priest of S. Callisto (1661–1673). Nuncio in Poland (1652-1660). (died 1681). Former Bishop of Lodi (1644–1669). He was the candidate of the Escadron, but was on the exclusion list of the Spanish.. Bichi, the Ambassador of the Grand Duke of Tuscany, remarked of him [Petruccelli III, p. 227], "C'est un homme qui a l'expérience du monde, connaît les affaires des princes, parcimonieux dans les dépenses, ce qui arrêterait les désastres de la chambre apostolique, bon curial, c'est-à-dire connaissant Rome et le gouvernement de l' État ecclésiastique." On another occasion he wrote [Petruccelli III, p. 232], "Quant a Vidoni, on parle bien de sa fortune, mal de ses moeurs, pire de sa justice."

- Gregorio Barbarigo (aged 44), Cardinal Priest of S. Tommaso in Parione (1660–1677). (died 1697). Bishop of Padua (1664–1697).

- Girolamo Boncompagni (aged 48), Cardinal Priest of SS. Marcellino e Pietro (died 1684). Archbishop of Bologna.

- Alfonso Litta (aged 61), Cardinal Priest of S. Croce in Gerusalemme (died 1679). Archbishop of Milan.

- Neri Corsini (aged 56), Cardinal Priest of Ss. Nereo ed Achilleo (died 1678).

- Carlo Bonelli (aged 58), Cardinal Priest of S. Anastasia Governor of Rome under Alexander VII. Nuncio to Philip IV of Spain. He died on August 27, 1676. His memorial inscription is in S. Maria sopra Minerva [V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma I, p. 502, no. 1938]. Great-grand-nephew of Pius V.

- Celio Piccolomini (aged 61), Cardinal Priest of S. Pietro in Montorio (died 1681).

- Carlo Carafa (aged 59), Cardinal Priest of S. Susanna (died 1680).

- Paluzzo Paluzzi degli Albertoni (aged 47), Cardinal Priest of Ss. XII Apostoli (died 1698). Bishop of Montefisacone e Corneto.

- Cesare Maria Antonio Rasponi (aged 55), Cardinal Priest of S. Giovanni a Porta Latina (died 1675). Legate in Urbino.

- Giannicolò Conti di Poli (aged 53), Cardinal Priest of S. Maria in Traspontina (died 1698). Bishop of Ancona and Numana.

- Giacomo Filippo Nini (aged 41), Cardinal Priest of S. Maria della Pace (died 1680).

- Carlo Roberti (aged 65), Cardinal Priest of S. Maria in Ara Coeli (died 1673).

- Vitalianus Visconti, Cardinal Priest of S. Agnese fuori le mura (died 1671).

- Giulio Spinola (aged 58), Cardinal Priest of S. Martino ai Monti (died 1691) .

- Innico Caracciolo (aged 63), Cardinal Priest of S. Clemente (died 1685). Archbishop of Naples (1667-1685)..

- Giovanni Delfino (aged 53), Cardinal Priest S. Salvatore in Lauro . Patriarch of Aquileia (1657-1699) (died 1699).

- Giacomo Rospigliosi (aged 39), Cardinal Priest of S. Sisto (1668-1672), and later of Ss. Giovanni e Paolo (1672-1684) Archpriest of the Liberian Basilica (1667?–1684). Prefect of the Segnatura. Previously member of his uncle's Spanish legation, Major Domo to Cardinal Chigi (nephew of Alexander VII). (died 1684). Nephew of Pope Clement IX

- Emmanuel Théodose de la Tour d'Auvergne de Bouillon (aged 26), Cardinal Priest without title. Received the titulus of S. Lorenzo in Panisperna on May 19 from the new pope. (died 1715)

- Ludovicus (Luis) Manuel Fernández de Portocarrero (aged 35), Cardinal Priest without title. Received the titulus of S. Sabina on May 19 from the new pope. Archbishop of Toledo and Primate of Spain (1677-1709) (died 1709). He did not enter the Conclave until April, his elevation having been announced only ten days before the death of the Pope.

- Francesco Nerli (aged 75), Cardinal Priest without title. Received the titulus of S. Bartolomeo all’Isola on May 19 from the new pope. (died November 6, 1670)

- Emilio Altieri (aged 79), Cardinal Priest without titulus; he had just been appointed, on November 29, 1669. He had previously been Prefect (Maestro di camera) of the Papal Household. Bishop of Camerino (1627-1670) (died 1676, as Pope Clement X).

- Giovanni Bona, O.Cist. (aged 60) [Mondovi], Cardinal Priest without title. Received the titulus of S. Bernardo alle Terme on May 19 from the new pope. Master General of the Reformed Congregation of the Cistercians in Italy for a term of three years (1651-1654) [Cardella VII, 199]. Carlo Emmanuele II of Savoy wanted to nominate him Bishop of Asti upon the death of the incumbent in October, 1655 [Ughelli-Colet, Italia sacra IV, 404], but Bona refused. He was instead appointed Master General of all the Cistercians by Alexander VII (Chigi), a post he held until he became a Cardinal in 1669. Before he became a cardinal, and afterward, he was Consultor of the SC of the Index, of the SC Rituum, the Propaganda, and of the SC of the Inquisition. He was a friend and protector of Fr. Enrico Noris. (died October 28, 1674). [His biography by Idelfonso Tardito, in Robertus Sala, Iohannis Bona...Epistolae selectae (Torino 1755), i-xix; his "Elogium" by Carlo Morotio, ibidem, xx-xxii]

- Francesco Maidalchini (aged 49), Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Via Lata (1666–1689). (died 1700).

- Friedrich von Hessen-Darmstadt, O.S.Io.Hieros (aged 54), Cardinal Deacon of S. Nicola in Carcere (died 1682). Imperial Ambassador at the Papal Court.

- Carlo Barberini (aged 40). Cardinal Deacon of S. Cesareo in Palatio (died 1704).

- Decio Azzolino (aged 47), Cardinal Deacon of S. Eustachio, formerly of S. Adriano al Foro Secretary of State of Clement IX (1667-1669). (died 1689).

- Giacomo Franzoni (aged 57), Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Cosmedin (1669–1670), formerly of S. Maria in Aquiro (died 1697). Bishop of Camerino (1666–1693).

- Francesco Maria Mancini (aged 64), Cardinal Deacon ofSS. Vito, Modesto e Crescenzia (1660–1670). (died 1672).

- Angelo Celsi (aged 70), Cardinal Deacon of S. Angelo in Pescheria , formerly of S. Giorgio in Velabro (died 1671). Prefect of the SC of the Council.

- Paolo Savelli (aged 48), Cardinal Deacon of S. Giorgio in Velabro, formerly of S. Maria della Scala (died 1685).

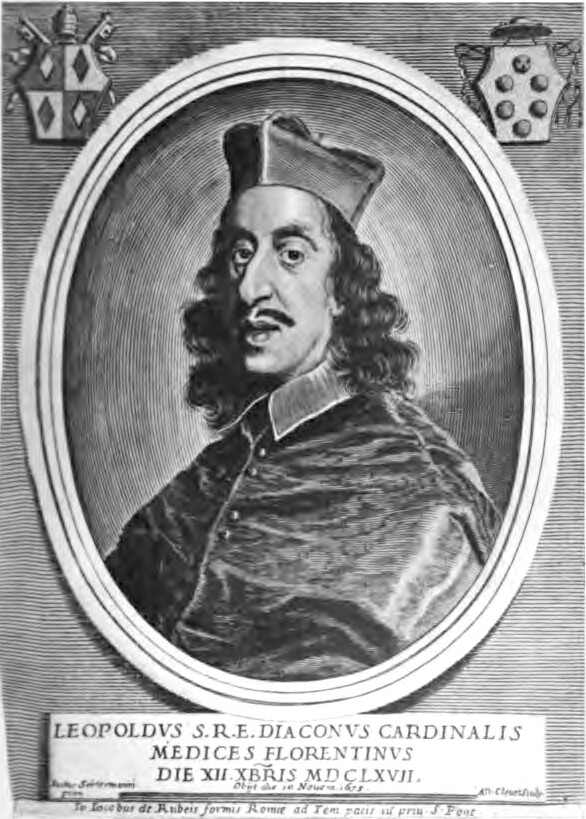

- Leopoldo de' Medici (aged 42) [Florentinus], brother of Ferdinand II and Cosimo III, Grand Dukes of Tuscany; brother of Cardinal Giovanni Carlo de' Medici (1644-1662). Created a cardinal by Pope Clement IX in 1667. Cardinal Deacon of SS. Cosma e Damiano (1668-1670), and then of S. Maria in Cosmedin (died 1675).

- Sigismondo Chigi (21), Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Domnica (1670) and then of S. Giorgio in Velabro (1670-1678) (died 1678, at the age of 28).

- Carlo Cerri (aged 59), Cardinal Deacon without Deaconry. Granted the Deaconry of S. Adriano al Foro on May 19 by the new pope

- Lazaro Pallavicino (aged 66), Cardinal Deacon without Deaconry. Granted the Deaconry of S. Adriano al Foro on May 19 by the new pope, Clement X. He became Cardinal Priest of S. Balbina in 1677. (died 1680)

- Niccolò Acciaioli (aged 39), Cardinal Deacon without Deaconry. Granted the Deaconry of Ss. Cosma e Damiano (1670-1689) on May 19 by the new pope. (died 1719).

- Bonaccorso Bonaccorsi (49), Cardinal Deacon without Deaconry. Granted the Deaconry of S. Maria della Scala on May 19 by the new pope. (died 1678)

- Girolamo Grimaldi (aged 74), Cardinal Priest of Sma. Trinità al Monte Pincio (1655–1675) Nuncio in France (1641-1643). Archbishop of Aix, France (1648–1685). (died 1685)

- Pascual de Aragón-Córdoba-Cardona y Fernández de Córdoba (aged 44), son of Don Enrique, fifth duke of Segorbe y Cardona, and Dona Catalina Fernandez de Cordoba. Cardinal Priest of S. Balbina (1661–1677). Archbishop of Toledo (1666–1677). Inquisitor General of Spain. . Member of the Council of State. Member of the Order of Alcantara. (died in Toledo on September 28, 1677)

- Luis Guillermo de Moncada de Aragón Luna de Peralta y de la Cerda (aged 56), son of the seventh duke of Montalto and Dona Juana de la Cerda. Cardinal Deacon without Deaconry (died 1673). Duke of Bivona.

Opening of the Conclave. 'Soggetti'

The Conclave of 1669-1670 lasted four months and ten days. It began on December 20, 1669. The Oratio de eligendo Summo Pontifice was preached by Antonio Malagonelli (detto Amadori) [Romae 1669]. The College of Cardinals was at full strength, seventy members. Fifty-seven cardinals entered conclave on opening day, joined on the next day by Cardinal Frederick of Hesse-Darmstadt, and on the day after that Cardinal Cacciolo. The Cardinal Camerlengo was present but ill, as was Cardinal Federico Sforza. On the day after Christmas Cardinal Borromeo entered conclave. Porto Carrero finally arrived in April. There were complicated comings and goings of cardinals who were ill, the especially severe winter no doubt playing its part, though the lowered quality of sanitary arrangements for a small army of men surely contributed. Three cardinals did not appear in Rome at all, and Cardinal Ludovisi was unwilling to enter conclave at all, despite canonical penalties.

According to the account of a conclavist-eyewitness, there were as many as twenty-one soggetti papabili, but this is ridiculous. One person on the list, for example, Cardinal Ginetti (bishop of Velletri), was eighty-five years old. The Dean, Cardinal Francesco Barberini, was only 73, but known throughout Europe for his stubbornness and anger. On the other hand Cardinal Brancacci of Naples, though not in any faction, had many qualities to recommend him in a deadlock.

Cardinal Facchinetti of Bologna, a gregarious friendly personality, was a candidate of Cardinal Barberini's group.

Giovanni Battista Cardinal Spada of Lucca was the candidate of the 'Squadrone volante' (the survivors of the cardinals created by Innocent X and Alexander VII), and Barberini's second choice. Cardinal Decio Azzolino, the Secretary of State of Clement IX and one of Innocent X's creations, was also working on his squadron to promote the candidacy of Cardinal Vidoni, whom he considered to be the best candidate to carry forward current policy [de Bildt, 19]. One of the best of their goals was to make the Papacy independent of all national pressures. Azzolino intended to use Christine of Sweden as an intermediary outside the Conclave to negotiate with the ambassadors of the important states, Spain, France, Venice and the Emperor. Msgr. Louis de Bourlement, the French agent, wrote to King Louis XIV on December 9 [de Bildt, 20]: "Le cardinal Azzolino apparemment va etre le negociant du conclave et aura en main toutes les factions."

Flavio Chigi, who led a group of perhaps twenty-four, had several candidates: d'Elci (who was opposed by Medici, and who died on April 13), Celsi, Bonvisi, and Vidoni. Nineteenth on the Conclavist's list came the 79 year-old Emilio Altieri, a Roman, a former diplomat, the late pope's Maestro di camera. Benedetto Odescalchi and Pietro Ottoboni, both future popes, were also under consideration, though both were too young in the opinion of many. And so it went.

The French King had Cardinal Albizzi at the top of his list (Albizzi had been an intimate of Cardinal Mazarin, and he was a strong and vocal opponent of Jansenism at the Holy Inquisition), though he realized that it would be a difficult business since Albizzi had enemies. Second on his list came Cardinal Buonvisi, the Bishop of Lucca and Legate in Ferrara, whose greatest disadvantage was his admittedly talented nephew, who was lamentably imbued with the doctrines of Tacitus and Machiavelli. Louis also viewed Cardinal Vidoni in a positive light. Louis XIV sent the Duke de Chaulnes to be his Ambassador Extraordinary at the Conclave, but until his arrival, French affairs were handled by the Auditor of the Rota for France, Msgr. Louis de Bourlemont. Chaulnes presented his credentials on January 22, 1670 [Diary of the Master of Ceremonies, Fulvius Servantius, in Gattico I, 36].

The Spanish, as usual, had a long list of "good cardinals": Odescalchi, Cybo, Spada, Facchinetti, Rossetti, Ginatti, Carpegna, and finally Barberini [Cardinal Medici to the Grand Duke (April 12, 1670): Petruccelli III, p. 235 n. 1; Medici had received the list from the Marquis de Astorga, the Spanish Ambassador].

The person who was the object of everyone's dislike was Cardinal Chigi. He had been the moving force and power in the Papacy during the two previous reigns, and no one wanted to see a third Papacy under the domination of Chigi. He, therefore, was anathema. And this opposition extended to any candidate who was one of his creatures or in his debt despite his large following. Cardinal Rospigliosi was particularly determined in this.

Factions

There were a total of six factions [Amelot de Houssaie, Relation du Conclave de MDCLXX (Paris 1676), 6; Bildt, 29]. The French faction had eight members: d'Este, Antonio Barberini, Orsini, Grimaldi, de Retz, Maidlachini, Mancini, and de Bouillon. Louis XIV had informed the Duc de Chaulnes that he did not want to use the exclusiva in the Conclave—except in the case of Francesco Barberini. The Spanish faction had ten members (de Bildt, 34): Medici, Hesse, Sforza, Raggi, Acquaviva, Pio, Visconti, Aragon, Moncada, and Porto Carrero. Cardinal Francesco Barberini commanded eight votes: Carlo Barberini, Ginetti, Brancaccio, Carpegna, Gabrielli, Fachinetti, and Rosetti (de Bildt, 39) The 'Squadrone volante' had twelve members: Azzolino, Ottoboni, Imperiali, Borromeo, Omodei, Gualtieri, Ludovisi, Cibò, Odescalchi, Santa Croce, Spada, and Albizzi (de Bildt, 40-41). Only the first six were a solid group, the latter six were less reliable. Flavio Chigi (cardinal-nephew at 20, and now only 39) led a faction of the adherents of Alexander VII, twenty-four in number: Sigismondo Chigi, d'Elci, Bonelli, Spinola, Vidoni, Carafa, Corsini, Piccolomini, Rasponi, Roberti, Bichi, Litta, Caracciolo, Boncompagni, Delfini, Barbadigo, Bonvisi, Franzoni, Conti, Paluzzi, Celsi, Nini, and Savelli (de Bildt. 43-45). The Rospigliosi party had eight votes: Nerli, Bona, Cerri, Acciaioli, Pallavicini, Bonaccorsi, and Altieri [de Bildt, 46-47].

Early Balloting

In the first ballot, on December 23, Barberini received 17 votes, Odescalchi 10, Cibo 8, Bona 6, d'Elci 2, and Celsi 1; no one else had more than four [Bildt, 269]. From then on, Barberini almost always came in first, but with 12 or 13 votes; he reached his maximum of twenty-five on January 15, but immediately fell back to 14. Cardinal Odescalchi, though some thought he might actually be elected, reached his maximum on February 25; he could only martial 15 votes. Thereafter Cardinal Rospigliosi, the deceased pope's nephew, showed considerable support, in the neighborhood of thirty votes; he was awarded a maximum of 33 votes, on March 10. But, as Bildt explains, both cases demonstrated not real support but rather the ability of the minority to martial enough strength to stop anyone [Houssaie, 40-43; Histoire des conclaves 3rd ed. II, 565]. Only twenty-three votes were needed for a virtual Veto. As Chaulnes remarked to Louis XIV on February 11 [Bildt, 243]:

... je crois trés difficile de prévoir où l' on se pourra déterminer par les fortes exclusions contre tous les trois sujets de la faction de Chigi. Le Cardinal Celsi par ses mœurs, et par Barberin; Bonvisi par Barberin, l’Escadron et Rospigliosi; et Vidoni par Chigi, les Espagnols et Médicis; Barberin méme n`y allant pas, mais sans exclusion.

Manipulations of 'the Crowns'

On the morning of February 10, the French Ambassador Chaulnes wrote to Cardinal de Retz that the election of Cardinal d' Elci could not be agreeable to King Louis XIV. Louis had made this clear in his Instructions for the Duc [Hanoteaux, pp. 234-235]:

Il y a un autre cardinal qui est d’Elci, que le Roi croit avoir intérêt de tenir éloigné du pontificat, non que Sa Majesté ait aucun sujet réel de se plaindre de lui et de sa conduite, ni d’aucun de ses proches, mais pour diverses circonstances dont un très grand concours sembloit obliger Sa Majesté et par prudence et même pour sa réputation à ne pas désirer voir et à ne pas souffrir qu’il soit exalté.Il est fils du comte Orso, autrefois principal ministre du grand-duc dans sa minorité, notoirement connu pour avoirété plus Autrichien pendanttoute la durée de son crédit que les Espagnols naturels même; le cardinal son fils a été imbu et élevé dans les mêmes maximes du père et toujours été pensionnaire des Espagnols et l’est encore aujourd’hui, a été nonce à la cour de l’empereur, doit son élévation à la continuelle protection que lesdits Espagnols lui ont donnée et est le sujet du sacré-collège qu’ils souhaitent de voir exalté préférablement à tous les autres.

Though a formal veto was never cast, this was enough to cause Cardinal de Medici and Cardinal Chigi to abandon the candidate [Bildt, 134-136]. Then Antonio Grimani, the Venetian Ambassador, suggested to Astorga, the Spanish Ambassador, and then to Chaulnes, the French Ambassador, that they should all approach the Sacred College and suggest the name of Cardinal Bonvisi, bishop of Lucca. Astorga advised him of the outrage that this would produce, and indicated that it had to be done discreetly; rumors of the plotting did reach the Sacred College, and there was the predicted outrage. On March 3, Cardinal Chigi proposed the name of Cardinal Bonvisi; when the scrutiny took place, Bonvisi received three votes. Chigi was humiliated, his faction was angry with him, and he vowed that the conclave would not end except with one of his faction being elected. Chigi and Medici made a demonstration in the scrutiny of March 10 by voting as a group for Cardinal Rospigliosi, who received a total of thirty-three votes out of the fifty-eight which were cast, a majority, but not the two-thirds majority needed for a canonical election.

Cardinal Odescalchi

Next it was Odescalchi. On March 10, in the evening, after the dramatic vote, a meeting was held in Cardinal Sforza's room. Several names were proposed—Carpegna, Nerli, Odescalchi—though hostility to Vidoni was the only certainty. Next day, however, Chigi and Medici decided to try Odescalchi. The fact that Azzolino was puitting it about that he was hostile to Odescalchi—it was only a ruse—made Odescalchi the more attractive. The two faction leaders began to canvass for votes.By the 17th of March it was all over Rome that a pope was about to be elected. Christine of Sweden tried to convince the French ambassador, on instructions from Azzolini, that the Squadrone Volante would not vote for Odescalchi. The truth of the subterfuges was revelaed when Azzolini left a message for Odescalchi with the latter's conclavist, who assumed (since Azzolini and Odescalchi had no friendly relations) that the message was intended for the French Cardinal de Bouillon next door, to whom he delivered the revealing note. At the voting of March 20, Odescalchi received only seven votes. The French Ambassador announced that no soggetto could ever be elected who did not have at least some obligation to His Majesty (King Louis XIV). That ended Odescalchi's candidacy.

Letters from Louis XIV and from de Lionne, dated March 16 and March 20, ordered the French ambassador, de Chaulnes, and the French party to try again to elect Bonvisi.

On Palm Sunday, March 30, 1670, there were sixty-six cardinals in Conclave [Gattico I, 361]

New Spanish Instructions alienate Cardinal Chigi

In Spain, the Council of State met on March 29 to consider dispatches from Rome and to draw up new instructions for its agents at the Conclave. It had supported Cardinal Vidoni, and was annoyed that he had been dropped. It blamed Ambassador Astorga for having brought the Spanish faction together with the Chigi faction, giving Chigi in effect the power of an exclusiva. Orders were signed by the Queen-regent to Astorga to repair the damage [de Bildt, 210-211], which quickly turned Chigi against the Spanish.

In April, after Easter, it was the turn of Brancaccio, who had been vetoed by Spain in the Conclave of 1667. The Venetian ambassador assured him that Spain was not hostile now, and so he consulted with Chigi (who did not encourage him) and Azzolini (who decided to consult with Christina, who agreed to work on his behalf, since Vidoni's chances were gone). But Medici as well was against him Cardinal Porto Carrero finally reached Civitavecchia on April 18, where he was met by the Spanish ambassador and members of the Spanish party in Italy; he visited Queen Christina on the 22nd, but all she obtained from him was an expression of good will toward Azzolino and the Squadrone; finally on the 23rd he entered conclave. He announced to their Eminences that he had not brought any exclusiva from the Court of Spain [Histoire des conclaves 3rd ed. II, pp. 568-569]. This caused the Vidoni faction to renew their efforts, since they believed they no longer had to fear a Spanish veto [Letter of Duc de Chaulnes, April 26, 1670].

Election of Cardinal Altieri

On the evening of the 27th of April, the French Ambassador Chaulnes, Cardinal Chigi and Cardinal Rospigliosi had a conference. Chaulnes was finally in a position to broker the election of a pope with the two parties whom he had been directed to bring together. It was agreed that a member of Rospigliosi's faction would be put forward. The heads of the two most influential factions, having come to the realization that neither would have either his first or his second choice, agreed that Cardianl Altieri, the man who had fewest enemies and the least negative baggage, would indeed be elected. Cardinals were individually approached in greatest secrecy, and told what would happen. On the evening of April 28, the ambassadors of the great powers were informed of their intention.

On the twenty-ninth of April, 1670 Emilio Cardinal Altieri, Cardinal Priest without red hat and without titular church, Bishop of Camerino, aged seventy-nine, was elected, with only two dissenting votes (Bildt, 222).

Altieri was crowned Clement X on May 11 in the Vatican Basilica, by Francesco Cardinal Maidalchini, the Cardinal Protodeacon; and on June 8, he took formal possession of S. Giovanni Laterano, his cathedral church [Cancellieri, 286-295]. Cardinal Orsini, the Archpriest of the Lateran Basilica presided. On the latter occasion the Masters of Ceremonies were Monsignors Fulvio Servantio, Petrus Antonius della Pedacchia, and Pietro Paolo Bona.

Clement X's first cardinal, Federico Borromeo (who was 53 years old), named on December 22, 1670, became Secretary of State. He had been Nuncio in Switzerland (1654-1665) and in Spain (1668-1670). Msgr. Gaspero Carpegna (aged 45, a relative of Cardinal Ulderico Carpegna), who had been made a cardinal on the same day as Federico Borromeo, was named Datary. Msgr. Camillo Massimi (aged 50), the Governor of the Conclave, was also named cardinal and became Maestro di Camera; he had been Nuncio in Spain from 1654-1656..

Bibliography

For the Conclave of 1670, see: "Conclave nel 1670, fatto dal Cardinal Rinaldo d'Este" (ms. Libreria Capponi, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana). Amelot de la Houssaie, Relation du Conclave de M.DC.LXX. (Paris: Frederic Leonard, 1676) [same text as in Gregorio Leti's Histoire des conclaves 3rd edition (1703)], 89 pp. duodecimo [The author obviously consulted the dispatches of the Duc de Chaulnes and other French materials]. [Gregorio Leti], Conclavi de' Pontefici Romani nuova edizione, riveduta, corretta, ed ampliata Volume III (Cologne: Lorenzo Martini 1691) 185-239. [The works of Gregory Leti are highly tendentious; once a Catholic and well-acquainted with Rome, he converted to Protestantism, and made it his literary business to entertain Europe with highly colored stories of the doings of Papal Rome. His facts come from conclavist sources, but his interpretations and personal characterizations should be looked on with suspicion] There is a list of contemporary accounts of the Conclave and other ceremonies in Cancellieri, p. 286 n. 4.

[Stefano Pignatelli], Candidatus papalis dignitatis ejusdemque promotor probe instructus, hoc est Eminentiss. Cardinalis Azzolini Aphorismi Politici... cum Commentario de electione Rom. Pontificis Jo. Frider. Mayeri, Doctoris et Professoris Theologi (Osnabrugae: Sumptibus Gothofredi Liebezeiti, literis Nicolai Spiringi, Anno 1691) [a small pamphlet of some 19 pp., near the end of the volume containing several authors' commentaries on papal elections].

Giuseppe de Novaes, Elementi della storia de' sommi pontefici da San Pietro sino al ... Pio Papa VII third edition, Volume 10 (Roma 1822) 208-209. Gaetano Moroni Dizionario di erudizione storico-ecclesiastica Volume 14 (Venezia 1842) 57 (thoroughly ridiculous); and F. Artaud de Montor, Histoire des souverains pontifes Romains Tome VI (Paris 1851) 90-91. F. Petruccelli della Gattina, Histoire diplomatique des conclaves Troisième volume (Paris 1865), 224-271 [His account,as he admits (p. 226), is based on the letters of Cardinal Leopold de Medici to his brother Duke Ferdinand II, with Chaulnes and Astorga to correct him]. T. A. Trollope, The Papal Conclaves as They Were and as They Are (London 1876), 346-376 [relying on the account of Gregorio Leti]. Charles Gérin, "Le Cardinal de Retz au Conclave, 1655, 1667, 1670 et 1676," Revue des questions historiques 30 (1881), 113-184.

Louis XIV's instructions to his Ambassador Extraordinary, the Duc de Chaulnes: Gabriel Hanotaux (editor), Recueil des instructions donnees aux ambassadeurs et ministres de France: Rome. Tome Premier (1648-1687) (Paris 1888) 228-244. A. Bozon, Le cardinal de Retz à Rome (Paris: Plon 1878)) 99-122. Charles Gérin, Louis XIV et le Saint Siège Volume II (Paris 1894), 390-407. Baron Carl Nils Daniel de Bildt, Christine de Suède et le Conclave de Clément X (1669-1670) (Paris: Plon 1906) [based on Cardinal Azzolini's correspondence with Queen Christina and with Cardinal Vidoni, and on state papers in The Vatican, Paris, Simancas and Venice, as well as other valuable sources].

Joannes Baptista Gattico, Acta Selecta Caeremonialia Sanctae Romanae Ecclesiae ex variis mss. codicibus et diariis saeculi xv. xvi. xvii. Tomus I (Romae 1753). Francesco Cancellieri, Storia de' solenni Possessioni de' Sommi Pontefici, detti anticamente Processi o Processioni dopo la loro Coronazione dalla Basilica Vaticana alla Lateranense (Roma: Luigi Lazzarini 1802).

Charles Terlinden, Le Pape Clément IX et la guerre de Candie (1667-1669) (Louvain 1904).