SEDE VACANTE 1590

August 27, 1590—September 15, 1590

September 27, 1590—December 5, 1590

Coins: Berman, p. 119 #1393-1407

from Rome (AV, AG), Fano (AR, billon), Macerata (AR, billon) and Montalto (billon)

ENRICO CARDINAL CAETANI (1550-1599), of a distinguished Roman family, son of Don Bonifacio, fourth Duke of Sermoneta and Caterina Pio di Savoia. was born on August 6, 1550, nephew of Cardinal Niccolò Caetani. He obtained a doctorate in canon and civil law from the University of Perugia. He was Patriarch of Alexandria (1585), and had served as Legate in Bologna (1585-87), and Nuncio to France and to Poland. He was created Cardinal by Sixtus V on December 18, 1585, and was sent to France as Legatus a latere (1589-1590) to deal with the crisis over the struggle for the French throne. His progress from Rome to Paris and back is unusually well attested, since one of the members of his suite was the Master of Ceremonies, Paolo Alaleone, who left notes in his Diarium [L. Caetani, Archivio della società Romani di storia patria 16 (1893), 24-25]; the embassy left Rome on May 11. In mid-July he met with King Henri of Navarre. Henri (IV) de Bourbon, King of Navarre, had been excommunicated in 1585 (and again in 1591) [Claude Fleury, Histoire Ecclesiastique 36 (1738), 283; 308-309]. Caetani arrived in Paris on July 21, eleven days before the assassination of Henri III—which rendered his mission pointless. He was immediately dispatched again in January of 1590, but not with credentials for Henri III, who was dead, or for Henri of Navarre. His credentials were received by the League Parliament of Paris on January 26, 1590, and he published his commission on February 6. The real Parliament, which was at Tours with the King, ordered the arrest of the Legate—which was never carried out. Another one of the members of Caetani's suite was Roberto Bellarmin, SJ. Despite instructions from the Pope to maintain a balance among the competing interests, which included Philip II of Spain (who was proposing his son as a candidate for the French throne), Caetani joined the Duc de Mayenne and the Holy League in proclaiming the Cardinal de Bourbon as King Charles X. Unfortunately, the Duc was defeated at the Battle of Ivry (1590) [See King Henri IV's announcement of the victory on March 14: Berger de Xivrey (editor), Recueil des lettres missives de Henri IV, Tome III (Paris 1846), p. 162], and the Cardinal de Bourbon died in prison shortly thereafter (May 9, 1590) of kidney disease, which caused retention of urine and fever [Registre-Journal de Henri IV et de Louis XIII, I. 2 (Paris 1837), p. 16]. With Henri de Bourbon besieging Paris, and Paris suffering from extreme famine, Caetani departed for Rome on Tuesday, September 24 [Pierre de l' Estoile, Mémoires pour servir à l' histoire de France... Registre-Journal de Henri IV et de Louis XIII, I. 2 (Paris 1837), p. 36]. He attempted to leave behind as Nuncio Filippo Sega, Bishop of Piacenza (1578-1596) [Sega was made a cardinal on December 18, 1591], but the parliament of Paris objected, on the grounds that the Pope was dead, and Caetani had no authority to turn his powers over to someone else. Cardinal Caetani did not reach Rome in time for the Conclave of September, 1590; he arrived shortly after the beginning of the second Conclave. As to his departure [Fleury, 327-328]:

Il prit pour prétexte d' un depart si précipité, la mort de Sixte V... afin d' être à tems pour se trouver au conclave, mais outre que son empressement fut fort inutile, les cardinaux de l' aïant pas attendu pour donner un successeur à Sixte, plusieurs crurent que cette raison n'étoit qu'un prétexte, et que les fraïeurs qu'il avoit euës durant le siége de Paris, les dépenses qu'il y avoit faites, le peu d' esperance qu'il avoit de procurer la couronne de France au roi d'Espagne, et la haine qu'il s'étoit attirée de la part des Francois, même de ceux qui étoient dans le parti de la ligue, le déterminerent à se retirer si promptement.

He had been named Camerlengo of the Holy Roman Church on October 26, 1587, and presided over the temporal affairs of the Church during the second Interregnum of 1590, and the Interregna of 1591 and 1592. He died on December 13, 1599. His younger brother, Camillo Gaetani, Patriarch of Alexandria (1588-1602) was Nuncio in Germany from January 1591 to June 1592, when he was made Apostolic Nuncio in Spain (October 1592-1602), where he died.

The Dean of the Sacred College since March 2, 1589, was Giovanni Cardinal Serbelloni (aged 71). He was born in Milan, a nephew of Pope Pius IV (whose mother was a Serbelloni), and was the first cardinal created when Pius became pope. He was named Bishop of Foligno in 1557. The new Pope, his uncle, immediately translated him to the Bishopric of Novara. On January 31, 1560 he was named Cardinal Priest in the title of S. Giorgio in Velabro to which he added the titulus of S. Maria degli Angeli in 1565. He chose to move to S. Pietro in Vincoli and then almost immediately to S. Clemente in 1565. In 1570 he moved to S. Angelo in Pescheria, and in 1577 to S. Maria in Trastevere. In 1578 he became Suburbicarian Bishop of Sabina, and shortly thereafter Bishop of Palestrina. He was promoted to the See of Frascati in 1583, and Porto and Santa Rufina in 1587. He died in 1591.

The Governor of the conclaves was Msgr.Ottavio Bandini, the Prefect of the Borgo [Eubel III, p. 53 n. 1]. He was born in Florence (October 25, 1558), and educated at Florence, Paris, Salamanca and Pisa (where he obtained a law degree, Doctor in utroque iure). He served as a lawyer and administrator in the Papal States from 1572. Gregory XIII made him a Protonotary Apostolic. Sixtus V made him governor of Fermo in 1586, and in 1590 he was Presidente delle Marche. Gregory XIV wanted to appoint him Datary in 1590, but the Olivares objected. Clement VIII made him Governor of Bologna in 1592. He became Archbishop of Fermo in 1595. Bandini was named Cardinal on June 5, 1596, and assigned the titulus of S. Sabina on June 21, 1596. In 1598 the Cardinal was sent to Picenum as legate to restore order in the face of brigands. In 1621 he was promoted to be Cardinal Bishop of Palestrina, which he exchanged for Porto and Santa Rufina in 1624. He became Dean of the Sacred College of Cardinals and Bishop of Ostia on September 7, 1626. He died in Rome on August 1, 1629 at the age of 72. He participated in the two Conclaves of 1605, and those of 1621 and 1623.

The Governor of the City of Rome was Msgr. Girolamo Matteucci, Archbishop of Ragusa (Epidaurus) and Sarno [Tria Conclavia, p. 3; Ughelli-Colet VII, 581; Gattico I, 398; Gams p. 414; cf. Eubel Hierarchia catholica III, 293; and Gauchat, Hierarchia catholica IV, 371].

The Captain General of the Papal Armies was Marchese Michele Peretti, grand-nephew of Sixtus V [Tria Conclavia, p. 3; Gattico I, 397]. The Lieutenant-General was Don Onorato Gaetani, fifth Duke of Sermoneta, the elder brother of Cardinal Gaetani; he had been Captain-General of the Papal Infantry at Lepanto in 1572 [Tria Conclavia, p. 3]. He was a Knight of the Golden Fleece.

The Custodian of the Conclave was Bernardo Savelli, Duke of Castro Condolsi [Tria Conclavia, p. 3]

The Masters of Ceremonies were Francesco Mucanzio and Paolo Alaleone [Gattico I, 398].

Background

In France, King Henri III had taken measures against the family of the Guise. On Christmas Eve, 1588, Cardinal Louis de Guise, the brother of Duke Henri de Guise, leader of the League (who had been killed on orders of the King) was executed. Catherine de Medicis had died on January 5, 1589 of pleurisy. Henri III was therefore the last of the Valois. By right and by agreement, his throne passed to his cousin, Henri de Navarre, the son of Alphonse, Duc de Bourbon, and Jeanne d' Albret, Queen of Navarre. Jeanne had been a Protestant, and from time to time so had her son Henri. He had converted to Catholicism in order to save his life, and he had been married to Marguerite de Valois, the King's sister. But he returned to his Protestant roots, and had been excommunicated by Sixtus V. Sixtus, moreover, had been strong in support of the wars of the League against the legitimate French government [e.g. Fleury, Histoire Ecclesiastique 36 (1738) 242].

In France, King Henri III had taken measures against the family of the Guise. On Christmas Eve, 1588, Cardinal Louis de Guise, the brother of Duke Henri de Guise, leader of the League (who had been killed on orders of the King) was executed. Catherine de Medicis had died on January 5, 1589 of pleurisy. Henri III was therefore the last of the Valois. By right and by agreement, his throne passed to his cousin, Henri de Navarre, the son of Alphonse, Duc de Bourbon, and Jeanne d' Albret, Queen of Navarre. Jeanne had been a Protestant, and from time to time so had her son Henri. He had converted to Catholicism in order to save his life, and he had been married to Marguerite de Valois, the King's sister. But he returned to his Protestant roots, and had been excommunicated by Sixtus V. Sixtus, moreover, had been strong in support of the wars of the League against the legitimate French government [e.g. Fleury, Histoire Ecclesiastique 36 (1738) 242].

On August 1, 1589, the French King, Henri III de Valois, was assassinated by at 22 year-old Jacques Clément, OP., a Dominican monk from Sorbonne near Sens. The King and King Henri de Navarre had just arrived at Paris, which had been under the control of the League, led by the Guises. Clément, enflamed by the hyper-Catholic oratory of the preachers of the League against the tyrant-king Henri, whose government was attempting to suppress their revolt against the Crown in the name of the Catholic faith, claimed that divine inspiration was impelling him to destroy the tyrant. Using forged passports he gained entry to the King's person, and when the king's attendants were distracted, stabbed the monarch in the lower abdomen. Clément was immediately executed by the King's attendants. The King died the next day, Wednesday, August 2, near 2 p.m., professing his full belief in the Catholic religion and his submission to the Pope. When the news reached Rome, Sixtus V held a Consistory on September 11, and praised the zeal and courage of the Dominican Clément [Fleury, Histoire Ecclesiastique 36 (1738), 266-274; Hübner II, p. 237].

On October 2, 1589, Pope Sixtus sent off a new Legate in France, Cardinal Enrico Caetani, who was not credentialled to King Henri of Navarre, but to the Duc de Mayenne and the Grand Council of the League. Caetani quickly made himself obnoxious to virtually everyone by his manipulations. His mission was to destroy the heretic King. He was given letters of credit for 100,000 ecus to carry out his mission. The Instructions prepared for him under Sixtus' direction, on September 30, 1589, began [in Baron Hübner's translation (p. 232) of a transcript of the original prepared by Father Agostin Theiner]

Premièrement, y est-il dit, Votre Seigneurie illustrissime ne perdra jamais de vue le but de cette légation, qui est la conservation de la sainte foi catholique dans tout ce royaume, l’extirpation de l’hérésie et des hérétiques, l’union et concorde de tous les princes, nobles et peuples pour le service de Dieu, le bien public, la conservation de cette couronne et de ce royaume, afin que, réunis sous un bon et catholique roi, ils puissent vivre tranquilles et en paix dans la religion catholique. Ce sera votre tâche de méditer constamment sur les modes et moyens d’arriver à cette fin... Deuxièmement, vous vous conformerez à tous les avertissements particuliers que Sa Sainteté vous a donnés sur ce que vous aurez à faire, tant pendant le voyage qu’après votre arrivée en France.

On Saturday May 5, 1590, the Duc de Mayenne, besieged in Paris, proclaimed the Cardinal de Bourbon (Cardinal Priest of S. Crisogono) King Charles X of France [Pierre de l' Estoile, Mémoires pour servir à l' histoire de France.... Registre-Journal de Henri IV et de Louis XIII, I. 2 (Paris 1837), p. 6]. This Charles de Bourbon was the third surviving son of Charles de Bourbon Duc de Vendôme and Françoise d' Alençon. The first surviving son was Antoine de Bourbon, the father of Henri IV.

In August of 1590, when Sixtus died, the leaders of the League were attempting to assemble their own Estates General in order to elect a new King of France, a Catholic king. They finally chose Charles II de Bourbon-Vendôme, the Cardinal de Bourbon, Cardinal Priest of S. Crisogono (1548-1590), who called himself Charles X. [portrait above, at right]. But Henri of Navarre won the war against the Cardinal and the Duke de Mayenne at the Battle of Ivry, and seized the persons of the Cardinal and the Archbishop of Lyons, Pierre d' Espinac. Sixtus V was compelled to begin an adjustment of policy, attempting to come to some sort of understanding with Henri IV [Platina, 194]. This only outraged the League members and the King of Spain. [Hübner, 291-316]. "King" Charles de Bourbon died on May 9, 1590, at the age of 67, in his prison at Fontenay [Spondanus, Continuatio Caes. Baronii Annalium III (Paris 1641), 722-723; Fleury, Histoire Ecclesiastique 36 (1738), 320-321]. Henri de Navarre, Henri IV to most of France, was in intense consultations as to what to do next. He was being gently pressured by a number of French ecclesiastics, including the Abbé du Perron, to re-convert to Catholicism, and in fact du Perron was secretly giving Henri instruction in the Catholic faith. [M. de Burigny, Vie du Cardinal du Perron (1768), 60-70] On the other hand, Philip II, who had once himself been King-Consort in England as well as King of Spain (His attack on England with the Spanish Armada had taken place in the previous summer), was frantic at the idea of a heretic king in France. He would rather himself assume the burden, than allow the Catholic faith and his own borders to be subverted [See the analysis of the letter and memorandum of Olivares to King Philip, February 24, 1586, in Letters and Memorials of William Cardinal Allen (1532-1594) Historical Introduction by T. F. Knox (London 1882) lxxxiii.]. With a Calvinist on the French throne, the Spanish Netherlands were in the greatest possible danger. War between France and Spain seemed imminent and inevitable.

Henri IV had sent François de Luxembourg, Duc de Piney, Peer of France, to Rome to negotiate about affairs in France, and especially the League [cf. Berger de Xivrey (editor), Recueil des lettres missives de Henri IV Tome III (Paris 1846), pp. 21-22]. He was in Venice on December 3, 1589 [Recueil des lettres missives de Henri IV, p. 157], a state which supported Henri IV. He arrived in Rome on January 8, 1590 [Fleury, Histoire Ecclesiastique 36 (1738), 305]. His reception by Pope Sixtus was friendly, and the Duke made headway in dispelling the Pope's negative views of King Henri. On March 10, the Spanish Ambassador the Count of Olivares, demanded that the Pope dismiss the Duke of Luxembourg and excommunicate the Cardinals and prelates in France who were supporting Henri IV. On March 22, Olivares appeared before the Pope and announced that unless the Pope proclaim the excommunication of the followers of Henri of Navarre, and that Navarre was forever incapable of ascending the throne of France, his master the King of Spain would renounce his allegiance to the Pope. Enraged, Sixtus stormed out of the meeting. But after a letter arrived from Philip II, he returned to his Spanish committments, and in fact negotiations for a new alliance between Sixtus and Philip began in July [Ranke, The History of the Popes and their Church II, p. 19, 27; Huebner, Sixte-Quint II, 324]. Support arrived from Philip II in the person of the Duke of Sessa, who was received in audience by Sixtus V for the first time on June 23, 1590 [Sessa to Philip II (June 30, 1590), in Huebner, Sixte-Quint III, no. 81, pp. 457-466]. An agreement was concluded, according to a report of the Duke of Sessa, on July 19, to support the efforts of the Spanish and the League to overthrow Henri of Navarre, with both money and troops [Huebner II, 324; text in Huebner III, no. 88, pp. 477-486]. France woud have a Catholic king. In a dispatch of Alberto Badoer to the Doge on July 28 [Huebener III, 492], he reported that the Congregation on French affairs had been asked to consider the proposition: An electio Regis Franciae, vacante Principe ex corpore sanguinis, spectet ad Pontificem? In the absence of a Prince of the blood, does the right to appoint a King of France belong to the Pope?

The pressure was then on the Pope to carry out his agreements. The Spanish would not be put off. Another Congregation on French Affairs was held on Tuesday, August 21, in the presence of the Pope, even though he was suffering from fever. He was pressed continually by the Spanish faction, especially by the Cardinal d'Aragona, and at the end he collapsed physically [report of Cardinal d'Aragona, given to the Duke of Sessa, who sent the report to Philip II: Huebner III, no.97, pp. 509-512].

Death of Pope Sixtus

Lorenzo Priuli, the Venetian Ambassador before the Holy See, wrote of Pope Sixtus in 1586, "The taste for accumulating money derails his projects....As a Cardinal, he suffered a bit from 'the gravel' (kidney stones). If his thought patterns and his anger don't agitate him, he will live a long time. But he preoccupies himself with many projects, he is passionate, he worries, he gets enraged to the point that his hands tremble.... Of the sixty living Cardinals [in 1586] scarcely a one loves him. They fear him and they regard him." (Alberi, Le relazioni, 297-329, especially 308; Petruccelli II, 263, 264). Priuli's successor, Giovanni Gritti, wrote on May 15, 1589 [Alberi, Le relazioni, 333-348; Petruccelli, 265], "The Holy See now lies entirely in the hands of Cardinal Montalto, a young man of seventeen years [bust at left].... Sixtus doesn't get along well with the Emperor ... and he is on very bad terms with the King of France. He esteems and likes the King of Spain, but the King is not satisfied with him, due to a letter written by the Pope, who was angry about the Pragmatic Sanction, and called the King a heretic and schismatic.... He is on good terms with the other princes, especially the Duke of Savoy.... He likes the Duke of Ferrara very much.... " [Alberi, Le relazioni, 345; Petruccelli, 266] He held the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Ferdinando I, in great esteem, because, Ferdinando de' Medici—who had been a Cardinal in 1585— had been instrumental in making him Pope [Alberi, Le relazioni, 345].

Lorenzo Priuli, the Venetian Ambassador before the Holy See, wrote of Pope Sixtus in 1586, "The taste for accumulating money derails his projects....As a Cardinal, he suffered a bit from 'the gravel' (kidney stones). If his thought patterns and his anger don't agitate him, he will live a long time. But he preoccupies himself with many projects, he is passionate, he worries, he gets enraged to the point that his hands tremble.... Of the sixty living Cardinals [in 1586] scarcely a one loves him. They fear him and they regard him." (Alberi, Le relazioni, 297-329, especially 308; Petruccelli II, 263, 264). Priuli's successor, Giovanni Gritti, wrote on May 15, 1589 [Alberi, Le relazioni, 333-348; Petruccelli, 265], "The Holy See now lies entirely in the hands of Cardinal Montalto, a young man of seventeen years [bust at left].... Sixtus doesn't get along well with the Emperor ... and he is on very bad terms with the King of France. He esteems and likes the King of Spain, but the King is not satisfied with him, due to a letter written by the Pope, who was angry about the Pragmatic Sanction, and called the King a heretic and schismatic.... He is on good terms with the other princes, especially the Duke of Savoy.... He likes the Duke of Ferrara very much.... " [Alberi, Le relazioni, 345; Petruccelli, 266] He held the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Ferdinando I, in great esteem, because, Ferdinando de' Medici—who had been a Cardinal in 1585— had been instrumental in making him Pope [Alberi, Le relazioni, 345].

On August 24, it was reported by the Roman agent of the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Giovanni Niccolini (son of Agnolo Niccolini, who had been envoy of Cosimo I to Pope Paul III), that the Pope was ill with a continuous fever, a fact which was also passed on by Cardinal Girolamo Della Rovere, Archbishop of Turin, to the Duke of Savoy on the same day; he noted that the Pope had given up wine and fruit and was putting himself in the hands of his doctors, a resolve that lasted exactly one day. Sixtus' Chief Physician (archiatros) was Antonio Porti, who had written a book de peste. The progress of the Pope's fever (malaria, probably) from Tuesday, August 21 to Sunday, August 25 is detailed by the Venetian agent, Alberto Badoer, in a dispatch of August 25. The anonymous Conclave narrative [Tria conclavia, 1] has it that the doctors advised he take a medicine that caused evacuation of his stomach, but the result was the opposite of what was intended—the fever actually increased. Paolo Alaleone also made notes in his Diarium [Tempesti II, 317]:

Sabato sera la febbre di Sua Beatitudine si convertì di terzana in continua. Et in oltre la Domenica mattina li vennero quattro accidenti, et perciò fu conosciuto mortale, et il giorno dopo pranzo in fretta mandò per li Cardinali Montalto, Pinelli et Giustiniani, à quali si crede desse qualche avvertimento, o forse fecesi promettere qualche cosa. Lunedi assistette alla persona di Sua Santità il Cardinale Aldobrandino, che come Sommo Penitentiero si crede gli amministrasse i Santissimi Sagramenti, e Montalto sino che spirò sempre vi stette assistente; et finalmente detto giorno a hore 22. passò di questa a miglior vita.

Pope Sixtus V (Peretti) died at his residence at Monte Cavallo (Quirinale) on Monday, August 27, 1590, near sunset, of malarial fever, his condition exacerbated by repeated angry discussions with the Spanish Ambassador, the Count-Duke of Olivares. At the papal bedside were twenty-seven of his thirty-three creature, including the Major Penitentiary, Cardinal Ippolito Aldobrandini. The Pope received Extreme Unction, but was unable to receive the Holy Communion [Tria conclavia, 2; Platina, 203-204]. Speaking more frankly and more maliciously, the Duke of Sessa wrote to the Spanish Minister Ydiaquez [in Baron Hübner's French translation, Sixte-Quint II, p. 349]:

Ce soir, à sept heures, le pape est mort sans confession. Il y a un cardinal qui dit que depuis des années il ne s'est pas confessé. Que Dieu l' accueille dans sa gloire! Il n'aurait pu mourir à un moment plus désavantageux pour sa réputation, car il laissera plus mauvais renom qu'aucun autre pape depuis bien des années.

It is said that at the moment of Pope Sixtus' death a sudden thunderstorm burst out, and the papal arms at the entrance to the Bridge of the Jews was struck by ligntning. It was taken as a bad omen. Because of the storm (It was, after all, the end of August, and such storms are normal), and also the lateness of the hour, the cardinals assembled, who should have held a Congregation, put the business off until the next day. In the meantime, the body was opened and the internal organs were found to be healthy; however, in summitate vero cerebri vesicula aqua repleta reperta fuit [Tria conclavia, 2].

Upon the news of his death, Sixtus' subjects rioted, and attempted to tear down the statue of their master which had been erected on the Capitoline; the College of Cardinals intervened, however, and the Constable Colonna (the husband of the Pope's grand-niece) and Mario Sforza prevented the destruction. The People nonetheless passed a law, which was inscribed on marble and placed in a Hall of the Campidoglio, against putting up a statue of a pope while he was alive. [Platina, 205; dispatch of the Venetian agent, Alberto Badoer, August 27, 1590].

During the night after his death, the enbalmed body was placed in the Sistine Chapel. The next morning the Cardinals assembled at the Vatican and held the First Congregation in the Consistorial Hall. The The Vice-Chamberlain S.R.E., Msgr. Giustiniani, produced the molds for the lead bullae, which were ceremonially broken. The Fisherman's ring, which had been broken on the previous evening, was produced as well and shown to the Cardinals. At the First Congregation, as well, Marchese Michele Peretti was named Captain-General of the Papal Armies, and—at the demand of Cardinal Montalto—Don Onorato Gaetani was appointed Lieutenant-General. Cardinal Gaetani, who was still in France, was to be reappointed Legate and given a subvention of 25,000 ecus [Badoer, in Hübner, Sixte-Quint II, p. 350-351]. At the conclusion of the meeting, the Cardinals repaired to the Sistine Chapel for prayers at the body of the late Pope, and then they followed the Canons of the Vatican Basilica, who transported the body to the Basilica and placed it in the Chapel of S. Gregory. The funeral was scheduled for the next day in the Sistine Chapel of the Basilica.

The Funeral of Pope Sixtus V took place in the Vatican Basilica on Wednesday, August 29, 1590. Cardinal Gesualdo, the Vice-Dean of the College of Cardinals, sang the Mass. Afterwards, the Second Congregation took place in the Sacristy of St. Peter's. The body was interred in the Vatican Basilica on the third day after his death.

The Novendiales concluded on September 6, 1590, with a Requiem Mass in the Vatican Basilica, the Funeral Oration being pronounced by Baldo Catani of Castiglione (1553-1597), Protonotary Apostolic and Canon of the Church of S. Lorenzo in Damaso, a client of Cardinal Alessandro Peretti Montalto [Petramellari, 337; Novaes Introduzione I, 261]. A year later, on September 2, the body of Sixtus V was entombed in the Liberian Basilica (S. Maria Maggiore), in the Sistine Chapel which he had constructed [Catani, Pompa funerale celebrata dal Card. A. Montalto nella trasportazione della ossa di Sisto V da S. Pietro a S. Maria Maggiore (Roma 1591); Petramellari, p. 336].

The Views of the Powers

Three months before the Pope died, Giovanni Gritti, in his address to the Venetian Senate at the conclusion of his Roman embassy, remarked that the sogggetti papabili were Paleotto (Bishop of Sabina), Castagna (San Marcello), Como (Galli, Bishop of Frascati), Gian Girolamo Albano (aged 86), and several others. Those who showed the most favor to Venice were Santa Croce (Andreas von Austria, Bishop of Brixen), Cremona (Sfondrati), Albano, Federico Cornaro (Bishop of Padua), and Verona (Agostino Valieri).

Cardinal della Rovere, Archbishop of Turin, wrote to the Duke of Savoy, "Olivares is asking me why there is no Ambassador of France here. I told him that the ambassadorship is vacant, not only because of the absence of the ambassador, but because they have no king in France (Archives of Turin, Petruccelli, II, 278).

Sixtus had also been acting friendly toward Queen Elizabeth of England, in the hope, apparently, of enticing her back to the True Faith and restoring Church income. But the execution of Mary de Guise, Queen of Scots, in 1587, had been a severe blow. In the wake of the Spanish Armada of the summer of 1588, and the accession of Henry of Navarre in France, Elizabeth and Protestantism had only become stronger. England had important interests, political, economic and religious, in the Netherlands, which frightened the Spanish. Sixtus' attempts at rapprochement only enraged King Philip the more against the old Pope. He sent the Duke of Sessa as his ambassador to reinforce the Count-Duke of Olivares in Rome.

The Grand Duke of Tuscany was also very interested in the election in Rome. Ferdinand I de' Medici had been a cardinal himself before succeeding to the duchy, and he knew personally all of the cardinals. Several of his subjects were to be participants in the Conclave, and he had been treating with King Philip of Spain in both their interests, or so he said. He had sent a messenger to King Philip, assuring the King of his loyalty, and willingness to work with the royal agents for Philip's candidates, with the exception of Cardinal Facchinetti (Santi Quattro). He said the same things to the Spanish ambassadors in Rome, Olivares and Sessa. He was also closely cooperating with Cardinal Montalto, the late Pope's nipote. A letter (August 31) from the Marquis Muti, ambassador of Savoy, however, noted that Castagna was making a lot of noise, and that he was being supported by the Duke of Florence, though Cardinal Montalto believed he could exclude him. Likewise, Florence (he said) could scarcely stand Como. The ambassador himself kept pushing Della Rovere, but he admitted that the entire College was against him, as they were against any of the creature of Sixtus V. In his view, the papabili were: the elder Colonna, Como, Castagna, Santi Quattro, Cremona, Lancelotti, Santa Severina, Albano, San Giorgio, Pinelli, Aldobrandino, Camerino and Paleotto (Petruccelli, 279-80). In a confidential letter of September 5 to his agent Nicolini in Rome, however, the Grand Duke repeated the instructions he had given another agent, Vinta, to whom he had given his instructions for the Conclave: exclusion for Como, exclusion for Santi Quattro, exclusion for Della Rovere; if somebody excludes Mondovi, don't move. If Mondovi pushes himself forward using the Duke's name, disavow him (Petruccelli, 283). Vinta had spoken with Cardinal Montalto, who had agreed to the Grand Duke's instructions, but who was uncertain as to Ferdinando's recommendation of Cardinal Castagna. He needed, he said, time to reflect. He feared that Castagna was "too Spanish" [Petruccelli, 284].

According to Duke Ferdinando's ambassador to the Emperor Rudolph II, Curzio de Pichena, who had heard from the Nuncio that the Emperor had written to Cardinal Spinola in order to coordinate his own preferences with those of Philip II, the Emperor was supporting the Cardinal of Austria, Madruzzo, the two Gonzagas, and San Marcello (Castagna). [Petruccelli, 280]

Venice and Rome were on very bad terms. The Serene Republic was supporting Henri IV, and the Papal Ambassador in Venice, Msgr. Martinucci, had broken formal relations. He was withdrawn by the Pope in October, 1589 [Hübner II, p. 236, 242]. The Venetian Ambassador in Rome, Giovanni Gritti, presented his final Relazione to the Doge and Senate on May 15, 1589, covering the period 1585-1587 [Alberi, Relazione, pp. 331-348]. Leonardo Donato was sent as an Ambassador Extraordinary in 1589 to justify Venice's friendly policy toward Henri IV. Gritti was succeeded as Ambassador ordinary by Alberto Badoero in 1587. He was succeeded in Rome in 1590 by Giovanni Moro, who died in office in 1592.

The Cardinals

A list of the fifty-four Cardinals who were present at the Conclave of September, 1590, is given by Konrad Eubel, Hierarchia Catholica III, p. 53 n. 1. The same cardinals, less one, took part in the Conclave of October-December. A computation of the Cardinals who participated in the Conclave of 1590 is given by Alberi [Le relazioni, 293-296, and 349]. There were sixty-seven cardinals: seven were French, four Spanish, two Germans, two Poles, and the rest Italian. Giovanni Antonio Petramellari [pp. 366-369] states that there were sixty-five cardinals at the time of the election of Innocent IX: six cardinal-bishops, forty-six cardinal-priests, and thirteen cardinal-bishops. A list of fifty-four cardinals who participated, and thirteen who did not, is given by the anonymous author of Conclave, in quo Urbanus VII. papa electus est [in Tria conclavia (Francofurti 1617) 5-6].

-

Giovanni Serbelloni (aged 71), Suburbicarian Bishop of Ostia and Velletri (1589-1591), Dean of the Sacred College. He had formerly been Cardinal Priest of S. Maria Angelorum (1565-1570). He had begun his career as a cardinal as Cardinal Deacon of S. Giorgio in Velabro (1560-1565), and therefore he was sometimes called "S. Georgii". (died March 18, 1591)

- Alfonso Gesualdo (aged 50), Suburbicarian Bishop of Porto and Santa Rufina (died 1603) Vice-Dean (according to Giovanni Paolo Mucantio, the Master of Ceremonies: Gattico I, p. 339).

-

Iñigo de Aragona (aged 55 or 56), Suburbicarian Bishop of Frascati (died 1600). He was one of the Cardinals appointed by Sixtus V to deal with the Duke of Sessa and the other ambassadors in July, 1590. On July 19, sixteen articles were agreed upon between Sixtus and Philip II to reduce France to obedience to the Catholic faith [Huebner, Sixte-Quint II, 324].

- Marc' Antonio Colonna, Suburbicarian Bishop of Palestrina (died 1597)

- Tolomeo Galli (aged 63), "Como", Suburbicarian Bishop of Sabina, (d. 1607). Gregory XIII had made him Protector of Hungary [Törne, p. 230]

- Gabriele Paleotti (aged 68), Suburbicarian Bishop of Albano; formerly Cardinal Priest of San Martino ai Monti. Doctor in utroque iure (Bologna, 1546). Professor of Law at the University of Bologna. Canon of the Cathedral of Bologna. Refused the Bishoprics of Majorca, Ragusa, and Avignon, as well as the Vice-Legateship of Avignon. Auditor of the Rota. Sent by Paul IV to the Council of Trent. Appointed Bishop of Bologna by Pius V in 1566, and given the pallium of an Archbishop by Gregory XIII in 1582. Prefect of the Congregation of the Index (d. in Rome on July 20, 1597).

- Girolamo Simoncelli (aged 68), Cardinal Priest of S. Prisca (died 1605) Administrator of Orvieto. "Sanseverino" He was one of the Cardinals appointed by Sixtus V to deal with the Duke of Sessa and the other ambassadors in July, 1590 [Huebner, Sixte-Quint II, 324].

- Marco d' Altemps [Markus Sittich von Hohenems] (aged 57), nephew of Pius IV, Cardinal Priest of S. Giorgio in Velabro (d. 1595)

- Nicolas de Pellevé (aged 75), son of Charles de Pellevé, Sieur de Jouy and Hélène du Fay. His brother Robert was Bishop of Pamiers (1553-1579). Cardinal Priest of S. Prassede (1584-1594). Doctor of Laws (Bourges). Councillor of Parliament. Master of Requests. Abbot of S. Cornelius Compendiensis (in the diocese of Soissons) (1550-June,1552) [Gallia christiana IX, 441]. Named Bishop of Amiens by Henri II (1552-1564) [Gallia christiana X (Paris 1751), 1207]. He participated in the Estates General in Paris in January, 1557. He was sent to Scotland in 1559, as Nuncio of Paul IV, to deal with the Calvinist heretics. He accompanied the Cardinal of Lorraine to the Council of Trent (1562). Archbishop of Sens (1562-1591) [Gallia christiana XII , 95]. He was named cardinal by Pius V on May 17, 1570, but did not receive the titulus of SS. John and Paul until July 4, 1572, from the new pope, Gregory XIII. He was named Protector of Scotland and Ireland. He remained at the Papal Court until 1592. Henri III tried to get him to return to France in 1586, by sequestering his benefices, but the Pope intervened. Prefect of the SC of Bishops. An active member of the French "League" against Henri III and Henri IV at the Papal Court. Later Archbishop of Reims (1591-1594). In January-August, 1593, he was President of the Estates General (États de la Ligue) summoned to elect a King of France [Mémoires de la Ligue nouvelle édition V (Amsterdam 1758), 327]. (died March 24, 1594)

-

Luigi Madruzzi (aged 58), nephew of Cardinal Cristoforo Madruzzi, Cardinal Priest of S. Onofrio (d. 1600) Bishop of Trent. First choice of King Philip II, but, as Cardinal Morosini is said to have remarked, "Italy would fall prey to barbarians, which would be a shame to all" [Ranke, The History of the Popes, their Church and State tr. E. Foster (London 1853) II, p. 34 n.]

- Michele Bonnelli, OP (aged 49), Cardinal Priest of S. Lorenzo in Lucina, Cardinal Vicar of Rome, grand nephew and Nipote of Pius V, (d. 1598) "Alessandrino"

- Antonio Carafa (aged 52), Cardinal Priest of S. Giovanni e Paolo (died January 31, 1591)

- Giulio Antonio Santorio (aged 57), Cardinal Priest of S. Bartolommeo all' Isola (1570-1595). Bishop of S. Severina (1566-1570) (died May 9, 1602, as Bishop of Palestrina)

- Girolamo Rusticucci (aged 53), Cardinal Priest of S. Susanna, former Bishop of Sinigaglia (1570-1577). Protonotary Apostolic. Private Secretary of Pius V. Secretary of State 1566-1570. Created cardinal in 1570. Secretary of State of Sixtus V (1585-1590) [Moroni, Dizionario di erudizione historico-ecclesiastica 63 (Venice 1853), 280]. He was a member of the SC of the Council of Trent under Sixtus V [Tempesti, Storia della vita di Sisto V I, p. 373]. Created Vicar of Rome by Sixtus V in 1588 (1588-1603), in succession to Cardinal Bonelli. First Protector of the Congregation of the Hospitallers of S. John of God (died on June 14, 1603, and buried in S. Susanna [V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma IX, p. 534, no. 1042].

- Gian Girolamo Albani (aged 86), Cardinal Priest of S. Giovanni a Porta Latina (died April 15, 1591)

- Pedro de Deza (aged 70), Cardinal Priest of S. Girolamo dei Schiavoni/Croati (died 1600); Professor of Law at Salamanca. Grand Inquisitor

- Giovanni Gonzaga (aged 49), Cardinal Priest of S. Alessio (1587-1591), previously Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Cosmedin (1583-1587) (died December 23, 1591). Knight of S. John of Jerusalem

- Giovanni Antonio Facchinetti (aged 71), Cardinal Priest of SS. Quattro Coronati (died December 30, 1591) Pope Innocent IX

- Gianbattista Castagna (aged 68), grand-nephew of Cardinal Giacobazzi (1536-1540). Cardinal Priest of S. Marcello (died September 21, 1590) Doctor in utroque iure, Bologna. Protector of the Order of Preachers. Pope Urban VII

- Alessandro de' Medici (aged 55), son of Ottaviano de' Medici and Francesca Salviati (niece of Leo X). Cardinal Priest of S. Giovanni e Paolo. Bishop of Pistoia (1573-1574). Archbishop of Florence (1574–1605). (died April 27, 1605). "Cardinal of Florence" Fiorenza

- Niccolò Sfondrati (aged 55), Cardinal Priest of S. Cecilia (died October 16, 1591) Bishop of Cremona, Pope Gregory XIV

- Giulio Canani (aged 66), Cardinal Priest of S. Anastasia (d. 1592) Bishop of Modena; Doctor in utroque iure, Ferrara

- Agostino Valier (aged 59), Cardinal Priest of S. Marco (died 1606); Bishop of Verona

- Antonmaria Salviati (aged 53), Cardinal Priest of S. Maria della Pace (died 1602)

- Vincenzo Lauro (aged 67) Cardinal Priest of S. Clemente (died 1592) Bishop of Mondovi

-

Simeone Tagliavia d' Aragona (aged 40), [born in the Castle of Veziano, in the diocese of Mazzara in Sicily], son of Carlos, Duke of Terranova, Prince of Vetrana, and Margarita Ventimiglia; nephew of Cardinal Pietro Tagliavia. Taken to Spain as a child, studied at the Complutense; laureate in philosophy and theology. His father was Spanish ambassador to the Diet of Cologne, and spent nine years ruling Sicily in the name of the Emperor Charles V; he also ruled various province in Spain and the Netherlands for Philip II. Simeone was named a cardinal by Gregory XIII at the age of 33. Cardinal Priest without titulus. He was given S. Maria Angelorum in Thermis on May 20, 1585 [Eubel III, p. 65]. (died 1604) "Terranova" [Cardella, V, 218-219]. He was a principal supporter of Spanish interests in Rome.

- Filippo Spinola (aged 55), Cardinal Priest of S. Sabina (died 1593)

- Scipione Lancelotti (aged 63), Cardinal Priest of S. Salvatore in Lauro (died 1598) Doctor in utroque iure

- Giovanni Battista Castrucci (aged 49), Cardinal Priest of S. Maria in Aracoeli (died 1595) Archbishop of Chieti

- Federico Cornaro (aged 59), Cardinal Priest of S. Stefano Rotondo (died 1590) Member of the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem. Prior of Cyprus. Bishop of Bergamo. Bishop of Padua [died on October 4, just before the second conclave]

- Ippolito de Rossi, Cardinal Priest of S. Biagio (1587-1591), previously Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Porticu (1586-1587). "Papiensis" (died April 28, 1591).

- Domenico Pinello (aged 49), Cardinal Priest of S. Crisogono. Professor of Law at Padua; Archpriest of the Liberian Basilica (S. Maria Maggiore) (1587-1611). (died 1611)

- Ippolito Aldobrandini (aged 54), Cardinal Priest of S. Pancrazio (died 1605); Major Penitentiary; elected Pope Clement VIII

- Girolamo della Rovere (aged 62), Cardinal Priest of S. Pietro in vincoli (died January 25, 1592; not February 7) Archbishop of Turin

- Girolamo Bernerio, OP (aged 50), Cardinal Priest of S. Maria sopra Minerva. Former Inquisitor of Genoa. Prior of S. Sabina in Rome. Bishop of Ascoli Piceno (1586-1604) (died 1611) Ascoli

- Antonio Maria Galli (37), Cardinal Priest of S. Agnese in Agone (died 1620) Bishop of Perugia to 1591, then Osimo; "Cardinal Perusinensis"

- Costanzo da Sarnano, OFM Conv. (aged 59), Cardinal Priest of S. Pietro in Montorio (died 1595)

- Benedetto Giustiniano (aged 36), Cardinal Priest of S. Marcello (died 1621) Doctor of law, Genoa

-

William Allen (aged 58)

[Poulton in the Fylde, diocese of Lancaster], son of John Allen and Joanna Lister (of the diocese of York). Cardinal Priest of SS. Silvestro e Martino (died 1594). Student at Oriel College, Oxford, at the age of 15. M.A. July 16, 1554. Principal of St. Mary's Hall, Oxford (1556-1560). University Proctor, 1557. Named Canon of York in 1558, but he refused to take the Oath of Loyalty to Elizabeth I. In 1560 he fled to Louvain, where he undertook a controversy by pamphlet against Bishop Jewell on the subject of Purgatory and the efficacy of prayers for the dead. He returned to England for three years, but was forced to flee a second time. He was ordained in Mechlin in 1566. He settled in Douay, where, in 1568, supported by a subsidy from Sixtus V, he opened a college. In 1576, Allen was granted a Prebend in the Cathedral of Cambrai, which he relinquished upon becoming a cardinal. When the government of the Spanish Netherlands proved unfriendly (under pressure from England), Allen moved to Rheims in 1578, under the protection of the Guise family (relatives of Mary Queen of Scots) and was made a Canon in the cathedral there. He made his third journey to Rome in 1579. His college in Rheims was subsidized by Philip II of Spain and Pope Sixtus V. He obtained the Licenciate in Theology in 1570, and the Doctorate in 1571. He visited Rome again from December, 1575-July, 1576. He governed his college-in-exile until the Summer of 1585, when illness forced him to visit Spa; feeling better, he travelled to Rome, where he remained permanently. until On August 7, 1587, Sixtus V created him a cardinal, at the request of King Philip II of Spain [King Philip's memorial to the Pope, March 14, 1587, in Letters and Memorials of William Cardinal Allen (1532-1594) Historical Introduction by T. F. Knox (London 1882) lxxxvii-lxxxviii and 270-271]. Their plan—to overthrow Queen Elizabeth, and make Allen Archbishop of Canterbury, Papal Legate, and Chancellor of England—went down in the same storm that destroyed the Spanish Armada in August, 1588. Allen was nominated Archbishop of Mechlin (Malines) by Philip II in November, 1589 [Letters and Memorials, p. 436], but the See was a poor one and heavily in debt. Allen hesitated, and began negotiating with King Philip for a subsidy; and then Pope Sixtus died on August 27. In February 1590, however, he subscribes himself as Electus Machliniensis [Letters and Memorials p, 317-318].

[Poulton in the Fylde, diocese of Lancaster], son of John Allen and Joanna Lister (of the diocese of York). Cardinal Priest of SS. Silvestro e Martino (died 1594). Student at Oriel College, Oxford, at the age of 15. M.A. July 16, 1554. Principal of St. Mary's Hall, Oxford (1556-1560). University Proctor, 1557. Named Canon of York in 1558, but he refused to take the Oath of Loyalty to Elizabeth I. In 1560 he fled to Louvain, where he undertook a controversy by pamphlet against Bishop Jewell on the subject of Purgatory and the efficacy of prayers for the dead. He returned to England for three years, but was forced to flee a second time. He was ordained in Mechlin in 1566. He settled in Douay, where, in 1568, supported by a subsidy from Sixtus V, he opened a college. In 1576, Allen was granted a Prebend in the Cathedral of Cambrai, which he relinquished upon becoming a cardinal. When the government of the Spanish Netherlands proved unfriendly (under pressure from England), Allen moved to Rheims in 1578, under the protection of the Guise family (relatives of Mary Queen of Scots) and was made a Canon in the cathedral there. He made his third journey to Rome in 1579. His college in Rheims was subsidized by Philip II of Spain and Pope Sixtus V. He obtained the Licenciate in Theology in 1570, and the Doctorate in 1571. He visited Rome again from December, 1575-July, 1576. He governed his college-in-exile until the Summer of 1585, when illness forced him to visit Spa; feeling better, he travelled to Rome, where he remained permanently. until On August 7, 1587, Sixtus V created him a cardinal, at the request of King Philip II of Spain [King Philip's memorial to the Pope, March 14, 1587, in Letters and Memorials of William Cardinal Allen (1532-1594) Historical Introduction by T. F. Knox (London 1882) lxxxvii-lxxxviii and 270-271]. Their plan—to overthrow Queen Elizabeth, and make Allen Archbishop of Canterbury, Papal Legate, and Chancellor of England—went down in the same storm that destroyed the Spanish Armada in August, 1588. Allen was nominated Archbishop of Mechlin (Malines) by Philip II in November, 1589 [Letters and Memorials, p. 436], but the See was a poor one and heavily in debt. Allen hesitated, and began negotiating with King Philip for a subsidy; and then Pope Sixtus died on August 27. In February 1590, however, he subscribes himself as Electus Machliniensis [Letters and Memorials p, 317-318].

Gregory XIV gave Cardinal Allen a pension, and bestowed upon the English College in Rome an annual pension of 100 scudi a month. He was a member of the committee of Cardinals to revise the Bible published by Sixtus V. Allen died, impoverished and in debt, in Rome on October 16, 1594, and was buried in the Church of the Holy Trinity attached to the English College. [Thompson Cooper, Dictionary of National Biography I (1885), pp. 314-322. N. Fitzherbert, De antiquitate et continuatione catholicae religionis in Anglia, et de Alani cardinalis vita (Romae 1608), 55-100]. At the time of the Conclave he was so poor that the new Pope, Urban VII, granted him 1000 crowns, and cancelled his debt to Sixtus V of 3000 crowns. - Scipione Gonzaga (aged 47), Cardinal Priest of S. Maria del Popolo (died 1593) Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem

- Antonmaria Sauli (aged 49) [Genoa], son of Ottaviano Sauli. Cardinal Priest of S. Stefano al Monte Celio. Under Gregory XIII he was Nuncio in Naples; Nuncio Extraordinary in Portugal. Named Archbishop of Genoa by Sixtus V (1585-1591). Prefect of the fleets, and Legate for preparing a fleet (April 6, 1588-May 7, 1590) (died August 24, 1623)

- Giovanni Palotta (aged 42) [of Caldarola in the Diocese of Camerinum], Cardinal Priest of S. Matteo in Merulana (died 1620) former Archbishop of Cosenza, Archpriest of the Vatican Basilica. Papal Datary

- Juan Hurtado de Mendoza (aged 42), Cardinal Priest of S. Maria in Trastevere (died January 6 or 8, 1592).

-

Giovanni Francesco Morosini (aged 53), [Venetus], son of Pietro Morosini and Cornelia Cornara (September 30, 1537-January 10, 1596). Cardinal Priest of S. Maria in Via (1590–1596). He was Legate in France (1587-1589) for Sixtus V when created cardinal, even though he had a relative in the Sacred College, Federico Cornaro. He had been a strong supporter of the League (led by the Guise family) against the legitimate King of France, Henri III, and against the arrangement that would eventually pass the throne to Henri of Navarre. He had objected to the plan to have a meeting between Henri of France and Henri of Navarre, and asked permission to retire to Rome—which was refused ; the meeting took place on April 30, 1589 [Fleury, Histoire Ecclesiastique 36 (1738), 258-259]. He was recalled, and lived for some time under a cloud, until Sixtus' view of French politics began to change; there was a formal reconciliation at a Consistory on March 17, 1590 [Alberto Badoer to the Doge of Venice, in Hubner, Sixte-Quint II, p. 493].

His career had begun when he joined the suite of Ambassador Badoar in the Venetian embassy in Madrid. He also served in Savoy, France, and Poland. He was Bailie in Constantinople for Venice. Appointed Bishop of Brescia (1585–1596) by Gregory XIII, he was sent as ambassador to Constantinople. He died of a stroke in Brescia on January 10, 1596, and was buried in the Cathedral there. -

Mariano Pierbenedetti (aged 52) [Camerino]. Cardinal Priest of SS. Marcellino e Pietro (1589-1611) "Camerino" . His uncle, who was a close friend of Gregory XIII, brought him to Rome and obtained benefices for him. He was educated at the Collegio Romano by the Jesuits, and received a doctorate in 1574. Prior then Abbot of the Canons of Martorano. Bishop of Martorano (1577-1589), consecrated by Cardinal Felice Peretti Montalto, OFM.Conv., the future Pope Sixtus V. Prefect of the City of Rome from August 20, 1585, to December 20, 1587 [C. Weber, Legati e governatori dello Stato pontificio (1994) 360]. Prefect of the Consulta. Prefect of all the congregations (1592), and thus, for all practical purposes, prime minister. He died on January 20, 1611, and was buried in S. Maria Maggiore.

-

Gregorio Petrocchini del Montelbero (aged 55) [Pisanus, Montelparense], Cardinal Priest of S. Agostino (1590-1608). A member of the OESA, studied philosophy and theology at Macerata; obtained the grade of Magister. Regent of his Order in Sicily. Elected Prior General of the OESA in 1587, under the influence of Gregory XIII, who had ordered him back to Rome for the election. He conducted successful visitations of the houses of his Order, and Gregory XIII ordered him to do the same in Spain, where he won the favor of Philip II. Philip endowed him with an annual pension of several thousand gold ducats. He was created cardinal by Sixtus V on December 20, 1589. He died on May 19, 1612. "Montelbero"

-

Francesco Sforza di Santa Fiora (aged 28), [Born at Parma, on November 6, 1562]; his father was Conte di Santa Fiore; his mother Catharina was a relative of Pope Julius III. Grand-nephew of Pope Paul III. Nephew of Cardinal Guido Ascanio Sforza. Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Via Lata (December 5, 1588–November 13, 1624) Grand-nephew of Pope Paul III.

- Alessandro Damasceni Peretti (aged 19), Cardinal Deacon of S. Lorenzo in Damaso (died 1623); Vice-Chancellor of the Holy Roman Church, grand-nephew of Sixtus V "Montalto"

- Girolamo Mattei (aged 43), Cardinal Deacon of S. Eustachio (died 1603) Doctor in utroque iure, Bologna

- Ascanio Colonna (aged 30), Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Cosmedin (died 1608). Knight of Malta, Doctor in utroque iure, Alcalá. Archpriest of the Lateran Basilica [Gattico I, p. 396].

- Federico Borromeo (aged 26), Cardinal Deacon of S. Agata alla Suburra (1589–1591), then of S. Nicola in Carcere (from January 14, 1591–1593). His confessor was Fr. Filippo Neri (died 1631) Doctor of Law, Pavia. Attached to Cardinal Altemps; a supporter of the Spanish faction [Rivola, p. 157]

- Agostino Cusani (aged 48) [Milan], patrician of Milan, of the family of the Counts of Somma. Cardinal Deacon of S. Adriano al Foro (1589–1591). Doctor in utroque iure Gregory XIII appointed him a Cleric of the Apostolic Camera; he was promoted Auditor of the Apostolic Camera. Sixtus V named him a cardinal on December 14, 1588. (died October 20, 1598).

- Francesco Bourbon del Monte Santa Maria (aged 41), Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Domnica (died 1627) Doctor of law

- Guido Pepoli (aged 30) [Bononiensis], Cardinal Deacon of SS. Cosma e Damiano (died 1599). Former Treasurer of the Apostolic Camera. Doctor in utroque iure, Siena

- Andreas von Austria (aged 31) Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria Nova (died 1621) nephew of Emperor Charles V and also of Emperor Ferdinand I.

- Albrecht von Austria (aged 29), son of Emperor Maximilian II. Cardinal Priest of S. Croce in Gerusalemme (1580–1598). He was Papal Legate in Portugal and the Algareve [Bullarium Romanum IX (Augustae Taurinorum 1865), p. 515], and Viceroy of Portugal 1585-1595 (died 1621)

- Gaspar de Quiroga y Vila (aged 78) Cardinal Priest of S. Balbina (died 1594) Archbishop of Toledo

- Hughes de Loubenx de Verdalle (aged 59), Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Portico (died 1595) Grand Master of the Sovereign order of the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem (1582-1595).

- François de Joyeuse (aged 28), son of Guillaume de Joyeuse, Marechal de la France, and Maria de Batarnay; brother of Anne, duc de Joyeuse, Peer and Admiral of France, Governor of the Duchy of Normandy. Cardinal Priest of Sma Trinità al Monte Pincio (1587–1594). Former Archbishop of Narbonne (1582-1589) [Gallia christiana 6, 117-118]. Archbishop of Toulouse (1589-1604) [Eubel III, 315; Gauchat IV, 340]. Protector of France before the Holy See (1587-1589; 1596-1615) On May 23, 1590, he had held a Council at Toulouse [Fleury, Histoire Ecclesiastique 36 (1738), 344-345; Mansi, Sacrorum conciliorum nova et amplissima collectio 36.2, p. 351] (died 1615)

- Jerzy Radzvil (Radziwill) (aged 34), of the Dukes of Olika (Lithuania). Named a Cardinal Priest on December 12, 1583, by Gregory XIII, but was not named Cardinal Priest of S. Sisto until July 14, 1586 (1586-1600). Born a Calvinist, and orphan at twelve, educated at Leipzig. Converted to Catholicism in 1572. Studied at Jesuit institutions in Poznan, Vilnius (Wilna), and Rome. Travelled to Rome in 1575, and with the consent of King Stefan Bathory, was named Coadjutor of Wilna (by 1576, when he was in Rome), but with the proviso insisted upon by Pope Gregory XIII that he complete his studies in Rome. During this time he made a pilgrimage to S. James at Compostela. Bishop of Wilna (1579-1591). He was made Viceroy of Livonia by King Sefan (1582). He was not ordained a priest, however, until April 10, 1583, and was not consecrated a bishop until December 26, 1583. Bishop of Krakow (August 15, 1591-January 21, 1600). He was also named Legatus a latere to King Sigismund of Poland (1587-1632) and to the Emperor Rudolf II (1576-1612). Having arrived in Rome early in January, 1600, with the intention of taking part in the Jubilee, he died in Rome on January 21, 1600, and was buried in the Gesu [V. Forcella, Inscrizione delle chiese di Roma X, p. 463, no. 746].

- Andreas Bathóry (aged 24), Cardinal Deacon of S. Adriano (died 1599) nephew of king Stephen Bathory of Poland

- Rodrigo de Castro Osorio (aged 67) Cardinal Priest of SS. XII Apostoli (died 1600) Archbishop of Seville

- Charles de Bourbon de Vendome (aged 28), Cardinal Deacon without a deaconry. Archbishop-elect of Rouen (never ordained, never consecrated) [Ciaconius-Olduin IV, 75; Gallia christiana XI, 101]. He died at S. Germain-des-Pres on July 30 or 31, 1594 of tertian fever and dropsy. "Vindociniensis"

-

Enrico Caetani (aged 40), Cardinal Priest of S. Pudenziana (1586-1599). Doctor in utroque iure, Perugia; Patriarch of Alexandria (1585-1586), Cardinal Camerlengo. In 1586 he was appointed Legate in Bologna; he was recalled to Rome on October 26, 1587, and succeeded by Cardinal Montalto. Legate in France: Pope Sixtus spoke with satisfaction at a Consistory on February 12, 1590, about his reception in Paris [Laemmer, Meletematum, p. 233]; his report on heretics at the Sorbonne was read and discussed in Consistory on June 13. On Tuesday, September 24, 1590, after the news of the death of Sixtus V arrived, Caetani departed for Rome [Mémoires pour servir à l' histoire de France... Registre-Journal de Henri IV et de Louis XIII, I. 2 (Paris 1837), p. 36]; in Rome a new Pope had already been elected. Caetani arrived in Rome in time to enter the second conclave on October 10 [Fleury, Histoire Ecclesiastique 36 (1738), 340]. (died 1599)

- Charles de Lorraine-Vaudemont (aged 23), son of Charles, Duc de Lorraine, and Claude, daughter of King Henri II. Cardinal Deacon of S. Agata in Suburra (died 1607)

- Philippe de Lenoncourt (aged 63), Cardinal Priest of S. Onofrio (1588-1592). (died December 13, 1592)

-

Pierre de Gondi (aged 58), brother of Marshal de Retz. Cardinal Priest of S. Silvestro in Capite (died 1616). Bishop of Paris. On August 17, 1590, he was sent by the government of Paris along with the Archbishop of Lyon, Pierre d'Espinac, to negotiate with King Henri IV about the siege of Paris and a surrender [Berger de Xivrey (editor), Recueil des lettres missives de Henri IV, Tome III (Paris 1846), p. 238; Pierre de l' Estoile, Mémoires pour servir à l' histoire de France.... Registre-Journal de Henri IV et de Louis XIII, I. 2 (Paris 1837), p. 29, 32-33], but on August 30 the siege was relieved by the Duc de Mayenne and the Duke of Parma. The Legate, Cardinal Caetani, and the Archbishop of Lyon presided at a Te Deum in Notre Dame.

Those who were at the Conclave but were ill included: Altemps, Madrucci, Pellevé and Cornaro; Serbelloni Alan and Carafa had also been ill, but recovered.

The September Conclave

The Conclave opened on Friday, September 7, with the Mass of the Holy Spirit being sung by Cardinal Alfonso Gesualdo, the sub-Dean of the College of Cardinals, in St. Peter's Basilica in the Chapel of Sixtus IV. The oration de pontifice eligendo was pronounced by Antonio Buccapedulio, Canon of the Vatican Basilica [Eubel III, p. 53 n. 2; Antonii Buccapedulii de pontifice max. declarando ad amplissimos S. R. E. cardinales oratio (Romae: ex officina Marcantonio Muretti 1590)]. The new regulations of Gregory XIII allowed the Cardinals, however many were present at the enclosing of the Conclave, to proceed to an election without consideration of those who had not arrived. This caused the cardinals to put aside their customary leisurely attitude toward appearing and being enclosed. There were forty-eight cardinals participating that day. In the evening, they assembled in the Pauline Chapel and did the necessary business to see to a smooth operation of the Conclave. The officers of the Conclave and the various attendants and staff were sworn in. After the meeting, the three senior members of the orders of cardinals, Cardinal Gesualdo, Cardinal Michele Bonelli and Cardinal Francesco Sforza, conducted an examination of the credentials of the various Conclavists. The Ambassadors of the various Catholic governments stayed in the Conclave area, engaging in conversations and negotiations with the Cardinals until midnight. A number of them had been recommending Cardinal Giambattista Castagna (aged 69), Cardinal Priest of S. Marcello, and the buzz in the Conclave that night was about his prospects [Tria conclavia, p. 7]. Castagna had already been noted as a soggetto papabile by the Venetian Ambassador, Lorenzo Priuli, four years earlier [Alberi, Le relazione, 322]. Another soggetto of discussion was Cardinal Marcantonio Colonna (aged 67), the Cardinal Bishop of Palestrina, though the Spanish were known to be hostile to his candidacy. It is said that the late Pope Sixtus V had believed and stated that the Cardinal of S. Marcello would be his successor.

The cardinals were, as always, divided into factions. Cardinal Montalto, nephew of the dead pope, a young man of only nineteen years, led the creature of Sixtus V. He usually listened to the advice of Cardinals Giustiniani, Camerino (Pierbenedetti) and Aldobrandino, in addition to that of his aunt Camilla Peretti. His aunt Camilla was inclined toward Cardinal Colonna's candidacy, and so was Montalto. Cardinal Sforza led those of Gregory XIII (among whom was Cardinal Castagna), and Cardinal Ascanio Colonna a group of twelve cardinals who adhered to his own cause (Leti, 206). Montalto and Ascanio Colonna were continually working for the candidacy of Cardinal Marcantonio Colonna, and Sforza and Cardinal Carlo Borromeo and a few of Borromeo's adherents opposed him. The Spanish too, though few in number, did not support Colonna. Montalto and Colonna commanded the largest bloc of votes, but not the thirty-two (on the first scrutiny) or thirty-six needed to elect a pope (once all fifty-four cardinals who attended had arrived).

On the next day, Saturday, September 8, the Birthday of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Masses were said in the Sistine Chapel, one of which was attended by the Dean of the Sacred College, even though he was said to be quite aged and ill. Joannes Paulus Mucanzio, Master of Ceremonies, remarked in his Diary [J. Catalano, Sacrarum Caeremoniarum sive Rituum Ecclesiasticorum Sanctae Romanae Ecclesiae Libri Tres (Romae 1750), 61]:

die viij Septembris Cardinalis Gesualdus supplens vices Cardinalis S. Georgii Decani adhuc convalescentis et debilis propter infirmitatem, in dicto Sacello Paulino celebravit Missam lectam de Spiritu Sancto, in qua praebuit omnibus Cardinalibus, fere, inquam, nam hac die nonnulli Cardinales Presbyteri devotionis causa propter Festum Nativitatis B. Mariae Virginis celebraverunt in Sacello Sixti IV. in quo ultra altare solitum, quatuor alia altaria ad commoditatem et usum Reverendissimorum Dominorum Cardinalium et Conclavistarum celebrare volentium erecta fuerunt.

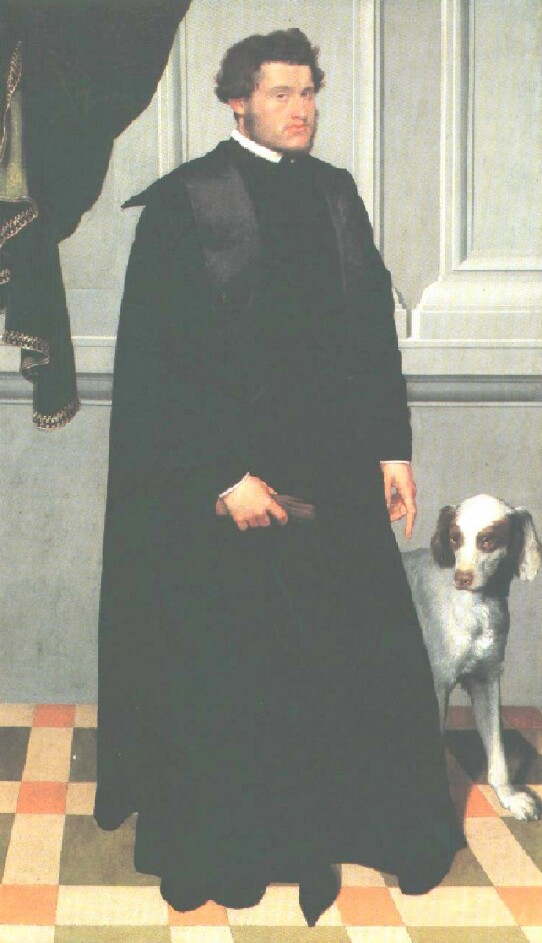

Afterwards, in the Capella Paolina, a scrutiny in the was held, but without a conclusive result. The ballots were burned in the Chapel itself [Tria conclavia, p. 8]. Later in the day Cardinal Ludovico Madruzzo (portrait at left) arrived from Trent and was received into the Conclave. Cardinal Madruzzo had brought with him the list of candidates acceptable to King Philip II of Spain (Sanseverino, Paleotti, Madruzzi, Como, Colonna, SS. Quattro and Cremona), and it is probably not accidental that one of them, the Cardinal of Como, Tolomeo Galli (aged 63), began to receive votes. Galli(o) had been the Private Secretary of Pius IV, and Gregory XIII's secretary of State. His candidacy was also supported by Cardinal Alessandrino (Michele Bonelli)—at least until Cardinal Montalto (Alessandro Peretti) declared himself publicly to be against Galli. The Florentines were also under instructions to exclude him. Alessandrino and his faction deserted Galli, and his candidacy was finished. (Histoire des Conclaves, 202; Petruccelli, 287). The next soggetto to be proposed was Cardinal Aldobrandini, but he was not acceptable to the Spanish, and his candidacy got nowhere. The rest of the day was occupied by a review by the Master of Ceremonies of all of the conclavists, who had to appear personally before him.

On Sunday, September 9, a second scrutiny took place. The Cardinal of Cremona, Niccolò Sfondrati, arrived during the reading of the votes and was allowed to enter the Paoline Chapel. Also present were Cardinals Albano and Cornaro, who had not taken part in the first scrutiny because of illness. All three read the papal bulls on conclaves and took the usual oaths. In the evening Cardinal Scipio Gonzaga entered the Conclave.

On Monday, September 10, Cardinal Madruzzo informed Cardinal Altemps and Cardinal Sforza (the leader of the creature of Gregory XIII) that one of the cardinals favored by the Spanish Crown was the Cardinal of Santi Quattro, Giovanni Antonio Facchinetti, one of the Inquisitors General at the Holy Office. But when they began to canvass for support for him, it was revealed that the Grand Duke of Tuscany and Cardinal Montalto (Alessandro Peretti) were against him, and so the proposal was abandoned. On the same day other names were making the rounds. Among them was Cardinal Sanseverino, Girolamo Simoncelli (aged 68), who attracted attention simply because Cardinal Madruzzo, King Philip's representative, had spoken well of him, but in his case it was the Grand Duke of Tuscany again and Cardinal Alessandrino who were found to be opposed to him. Later, the Cardinals assembled to receive the Cardinal of Pavia, Ippolito de' Rossi, who had entered the Conclave.

On Tuesday, the 11th of September, the third scrutiny took place. Although Cardinal Peretti and Cardinal Sforza continued to promote the candidacy of Cardinal Marcantonio Colonna with all the vigor at their command, there was no positive result. Nor did the balloting on Wednesday make any progress in finding a pope, despite the increasingly vocal frustration of Cardinal Sforza.

On Thursday, September 13th, the the sixth day, some of the cardinals attempted to place the tiara on the head of Marcantonio Colonna, amid scenes of wild excitement and tumult, but they did not succeed in their plan to press for election by "acclamation". This ended Colonna's chances, and Sforza was forced to look for another candidate. Among the creature of Gregory XIII, of whom Sforza was the leader, stood Gianbattista Castagna (aged 68). Castagna had been vigorously supported by the Grand Duke of Tuscany as his first choice for many months.

On Friday, the 14th, at the scrutiny, Cardinal Castagna received twenty votes [Tria conclavia, 18; Leti, 207, says 25 votes]. The size of his support was taken as a sign that it was only a matter of time until his candidacy would be successful. Cardinal Montalto made public remarks in favor of Castagna. Castagna was very acceptable to the Spanish. He was well known in Spain, where he had been Nuncio, and he had baptised King Philip's eldest daughter.

In the morning of Saturday, September 15, first by acclamation and then by a scrutiny, which was of course unanimous, Giambattista Cardinal Castagna, the governor of Bologna and Consultor of the Holy Roman Inquisition, was elected. It was decided to keep the election secret for some hours to allow the cardinals who were ill to be carried comfortably to their residences, and to allow the Conclavists to remove the property of the other cardinals to avoid the traditional sacking. In the afternoon, the new Pope was carried in procession to St. Peter's, where he received the hommage of the Cardinals in public. He then bestowed his Apostolic Blessing on the joyful crowds which had gathered. Later in the day, at the Vatican Palace, the Pope gave 2000 ducats to the Cardinal of Sens, Nicolas de Pellevé, who had spent all of his money on getting to the Conclave and had nothing now to live on; he also gave 1000 ducats to Cardinal Allen (founder of the seminaries at Douai and at Rheims, and one of the founders of the English College in Rome) for similar reasons. (Conclavi de' Pontifici Romani, 399;Histoire des Conclaves, 207-208)

Death of Pope Urban

Urban VII contracted a fever on the third day of his pontificate. He died of this malarial fever on Thursday, September 27, 1590, without having been crowned and without having been installed on his episcopal throne in the Lateran Basilica. His funeral oration was pronounced by P. Ugonius in the Vatican Basilica in the presence of the Cardinals on October 6, 1590.

On October 15, 1590, the news reached Paris that the new Pope, Urban VII (Castagni) had died on September 27. This was a great disappointment to the Spanish and the leaders of the League, since the new pope had promised his support to the League and to see to the destruction of the Huguenots [Pierre de l' Estoile, Mémoires pour servir à l' histoire de France... Registre-Journal de Henri IV et de Louis XIII, I. 2 (Paris 1837), p. 37]

The Second Conclave

The second Interregnum lasted from September 27 to December 5, a period of two months and seven days. Urban VII had created no cardinals, and therefore the Sacred College was substantially the same (except for the death of Cardinal Cornaro on October 4, 1590). Fifty-two of the sixty-five cardinals entered conclave on Monday, October 8. Two others arrived after the conclave began. Andreas of Austria was present, and, as Cardinal Protodeacon, crowned the new Pope [Petramellari, Ad librum Onuphrii Panvinii, pp. 344-345]. Cardinal Enrico Caetani, the Cardinal Camerlengo, had returned from his Legateship in France on October 10.

The second Conclave of 1590 was a very different affair from the first one. The Cardinals had subdivided into at least seven factions [Histoire des conclaves, 208]. Individual wounds from the previous conclave had not yet had time to heal. All of the plans of the previous conclave had been dashed, but there had been insufficient time for either cardinals or courts to reassess their positions or candidacies or receive instructions from their governments. Of necessity, therefore, the Second Conclave of 1590 would be a reapplication of the plans for the First Conclave. But consensus would be much harder to achieve. Hardly anyone, Cardinal or conclavist, was able to estimate accurately each soggetto's chances [Histoire des conclaves, 211]. It should be noted that the process of the accessio was not in use at this time.

The Spanish Ambassador, the Count-Duke of Olivares, was working hard for a personal friend of his, Cardinal Sanseverino (Girolamo Simoncelli, aged 68), who, as he declared, was King Philip's first choice. In the first Conclave King Philip [portrait at right] had sent a list, including the names of Sanseverino, Paleotti, Madruzzi, Como, Colonna, SS. Quattro and Cremona. But Simoncelli had always been vocal against the Spanish pretensions in Naples and Sicily as well as Ravenna. On the other hand, Simoncelli was thought to have the influence to bring the French cardinals to do what the king desired, or so the King believed. Simoncelli, the grand-nephew of Julius III and the last of his creations, had been a cardinal for 37 years and this was his eighth Conclave. He had been Bishop of Orvieto for eight years and subsequently Apostolic Administrator, and was noted for being unambitious for fame, promotion, or power. (Cardella, IV, 336-337). Cardinal Francesco del Monte, the leader of the Florentine faction, believed he could go along with Sanseverino's candidacy, since he already had the support of five or six creature of Sixtus V and there appeared to be other votes available in addition to the Spanish. When he was consulted, the Grand Duke wrote back to Monte that he thought Sanseverino better than any of the other candidates of King Philip—a change of position from the previous Conclave, and perhaps intended to prove to King Philip that the Grand Duke really was his friend. Monte was thus obliged to declare his support of Simoncelli openly. But there were difficulties. Cardinal Altemps was against Sanseverino, as were Sforza (The creature of Gregory XIII, now fourteen in number, were under his leadership), the two Colonnas, Alessandrino (Bonelli, leader of the creature of Pius V) and several of the Spanish faction. The cardinals perceived the weakness of Sanseverino's actual support and gave his candidacy little heed. Instead Olivares (and Madruzzo, inside the Conclave) turned their efforts toward the Cardinal of Cremona. (Histoire des conclaves, 214-216)

Once the Grand Duke was appraised of the collapse of Sanseverino's candidacy. he too turned his attention to Sfondrati, the Cardinal of Cremona, as much because he was being proposed by Altemps as because he could see nothing standing in the way of Cremona's chances. He would have the Spanish votes, the thirteen creature of Gregory XIII, Altemps and his party, and even perhaps Cardinal Montalto and his votes. The Duke of Mantua, however, hearing that Cremona was being touted, wrote to the Grand Duke of Tuscany, asking him not to extend his favor to Cremona, but to give him an exclusiva. Mantua had opposed Cremona in the previous conclave as well. Mantua also wrote to Candinal Montalto in exactly the same way. Montalto, whose brother, Don Michaele Peretti (aged 13), was a subject of the Grand Duke as Marquis of Incisa, was anxious to preserve the good will of the Grand Duke, and therefore agreed to oppose Cremona as well. Without the Florentines and the twenty-four creature of Sixtus V, Cremona's chances decreased greatly. (Conclavi, 414-415).

Cardinal Marcantonio Colonna had great hopes going into the Conclave for his own candidacy, and he believed he had committments from enough cardinals to make him pope in quick order. He had Montalto on his side, and was one of the seven cardinals who had the approval of the Spanish King. But the scrutiny proved that his hopes and his promised votes were illusory (those of Sens and Allen in particular). It was the opposition of Cardinal Carlo Borromeo, Markus Altemps, Iñigo de Aragona, and Francesco Sforza, along with Sens, Allen and Carafa, which brought together sufficient votes to provide an exclusiva. A surprising number of those votes came from the faction of Montalto (Histoire des conclaves, 242), indicating that he was having trouble keeping his faction together.

With Colonna's hopes gone, Montalto and Sforza turned their efforts toward Cardinal VIncenzo Lauro, Bishop of Mondovi, aged 67 [portrait at left]. Mondovi had degrees both in theology and medicine, and served his early apprenticeship with Cardinals Parisio, Gaddi, François de Tournon and Ippolito d' Este. His long career as a diplomat had brought him many acquaintances and friends (to say nothing of patients) among the royalty of Europe. He had been physician to the Duke of Savoy. He had a reputation for being observant and shrewd. He was a friend of Ignatius Loyola and of Camillo de Lellis, founder of the Hospital of the Incurabili. (Cardella, V, 204-210). Some, however, including Montalto, thought that he was too friendly with Luxembourg and the other French ministers. (Petruccelli, 284). Lauro would have made an excellent compromise candidate, but the beginning of the Conclave was not the right strategic time to bring him forward. A major miscalculation had taken place. The Grand Duke of Tuscany, moreover, had issued an instruction for his exclusion. Mondovi, besides, was not one of the cardinals who had been recommended by King Philip, and that might have played a part in his inability to attract votes (Conclavi, 420-421).

At the same time, the friends of Cardinal Aldobrandini (aged 54) decided to put him forward, but his candidacy attracted no enthusiasm. When Aldobrandini failed, Cardinal Gian Girolamo Albano suddenly became a subject of discussion. He had been a cardinal for twenty years, and was a distinguished canonist, with a quartet of important books to his credit. But he was eighty-six years of age, and he was infirm and frequently confined to bed for long periods of time. Those who were talking about him were no doubt counting on a short pontificate, during which they could seek new instructions and mend broken alliances. Albano himself realized that his time was past, and did not enter the competition (He died on April 15, 1591.) [Leti, Cardinalismo 209].

During the next three weeks scrutinies were held, but there were no developments, except suggesting new names and excluding them in the vote. Then the name of the Archbishop of Turin, Cardinal Girolamo della Rovere, aged 62, was proposed (Cardella, V, 247-248). He was a learned and honest man, and politically astute. He was a famous bibliophile, but his record of achievement was thin. His candidacy was dropped. In the midst of these twistings and turnings, the Spanish faction repeatedly tried to advance the candidacy of Cardinal Gabriele Paleotti, the Cardinal Bishop of Albano. He had been on the list of cardinals acceptable to King Philip which had been supplied by Cardinal Madruzzo at the first conclave. Paleotti was 68 in October, and had been a cardinal for 25 years. He had been a professor of Law at Bologna and a canonical consultant at the Council of Trent. A successful Bishop of Bologna since 1566, he had been active in implementing the Tridentine reforms. He had been the only Cardinal who opposed Pius V in Consistory on the raising of a tax to support the wars of religion in France. Sixtus V had appointed him Prefect of the Congregation on Rites, and Gregory XIII had placed him in the Congregation of the Index (Cardella, V, 102-109). But the first time a scrutiny was held with Paleotti as a candidate, he received only seventeen votes—to the great mortification of the Spanish faction. Obviously, the silent veto was being applied (Leti, Cardinalismo 210-211). Such vetos, using the ballot (One only needed one-third plus one of the votes being cast—in this case, eighteen), were a strategic maneuver to reduce the field of candidates and improve the chances of one's own candidate; they do not necessarily reflect badly on the intrinsic merits of the victim.

Next it was the turn of Cardinal Santi Quattro (Facchinetti), a great theologian, politician and courtier, but he too, despite his merits (He was elected Pope Innocent IX at the next Conclave), failed to make a showing.

Cardinal Montalto (Peretti: nephew of Pope Sixtus V) began to promote the candidacy of Scipio Cardinal Gonzaga (aged 47), but the latter firmly discouraged him. Then finally, it was time for Cardinal Madruzzo to speak with Cardinal Montalto. On December 4, Montalto, who had collected twenty-six votes into his faction (thirty-six votes were needed to elect), had his attention drected again to the name of the Cardinal of Cremona, Niccolo Sfondrati, one of the cardinals of Gregory XIII, as someone who might attract some votes from the Spanish and from the Sforza faction. (Leti, Cardinalismo 211-212). Like Paleotti he had been consecrated by Carlo Borromeo, participated in the Council of Trent, been a member of the Congregation of the Index, and administered his diocese with a reforming zeal (Cardella, V, 189-191).

Next morning, Cardinal Sforza was among those who called at Sfondrati's cell and escorted him to the Paoline Chapel. Late in the afternoon of December 5, 1590, Cardinal Sfondrati was elected with all the votes of the cardinals. The election had been viva voce, a scrutiny, but without paper ballots.

Gregory XIV (Sfondrati) was crowned on December 8, and took possession of the Lateran on December 13 [Gattico I, p. 396-402]. Cardinal Ascanio Colonna, Archpriest of the Lateran Basilica welcomed the Pope and presided over his installation [Cancellieri, p. 130]. Gregory XIV died ten months later, on October 16, 1591 [Laemmer, Meletematum, 234].