SEDE VACANTE 1352

December 6, 1352 —December 18, 1352

The Palace of the Popes, Avignon

New Cardinals

Clement VI was one of the greatest of papal nepotists (Souchon, 52). In 1342 he created eleven cardinals, including his brother Hughes Roger, OSB; his cousins Aymeric de Chalus, Gerard de la Garde, OP, and Guillaume d'Aigrefeuille; his nephews Bernard de la Tour, Guillaume de la Jugié, and Nicholas de Besse; and his cousin (or nephew) Adhemar Robert. To these relatives were added his nephew Pierre Roger de Beaufort (1348), his cousin Pierre de Cros (1350), and his nephew Raymond de Canilhac (1350). As the "First Life of Clement VI" (Baluzius I, column 265) puts it, "Suos enim fratres, nepotes, consanguineos, propinquos, compatriotas et servitores valde dilexit. Plurimos namque ex eis qui tempore suae promotionis erant in statu ecclesiastico, aut demum esse voluerunt, in altis et magnis praelaturis et dignitatibus sublimavit, multos vero inferioribus beneficiis fere ubique terrarum existentibus collocavit." The next Conclave would truly be a family affair.

Death of Pope Clement VI

A manuscript in the Vatican Library, cited by Theiner (Baronius-Theiner, sub anno 1352, no. 21; p. 537) states: Pauco tempore languens insperate, obiit Decembris die VI, anno Domini MCCCLII, Pontificatus sui anno XI, in Palatio Apostolico Avinionensi. According to one of the lives, he was percussus apostemate in dorso ("Fifth Life of Clement VI", Baluzius I, column 318). It is possible that this abscess, and the fever that accompanied the Pope in his last seven days, was evidence of a tumor, perhaps cancer (Déprez, 235 n. 1); Clement had been suffering the complaint for some time. Clement VI died on December 6, 1352, the Feast of St. Nicholas.

On the next day a funeral service was held in the Chapel of the Papal Palace, with the Patriarch of Alexandria, Jean de Cardailhac, preaching a sermon (Baluzius I, 909): A die VII mensis decembris qua die felicis recordationis Clemens VI fuit traditus ecclesiastic(a)e sepultur(a)e (Déprez, 236 n. 1). The body was then moved to the Cathedral of Notre-Dame des Domps, where the public novendiales took place. The Papal Almoner, Pierre de Froideville, distributed 400 livres among the poor. There were other large donations to each of the houses of monks and nuns in Avignon. Each day, according to the Will of Clement VI, fifty priests celebrated a mass for the repose of his soul.

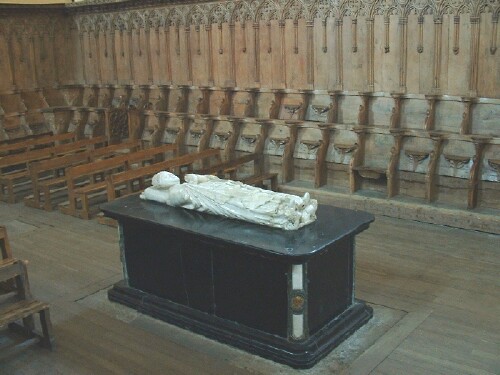

He was buried in the Cathedral at Avignon, where he remained for three months, but his remains were later transferred to his monastery of Casa-Dei (Chaise-Dieu, in the Auvergne). Five Cardinals, all relatives of the deceased Pope, escorted the cortege: Hugues Roger, Guillaume de la Jugié, Nicolas de Besse, Pierre Roger de Beaufort, and Guillaume d' Aigrefeuille.

Tomb of Pope Clement VI, in the Choir at La Chaise-Dieu

The Electors

Eubel Hierarchia Catholica I second edition, p. 19 note 3. Baumgarten, "Miscellanea Cameralia II," pp. 38-39. During his pontificate Clement VI (Pierre Roger) had appointed twenty-seven cardinals, in three creations. Seven of them had died during his reign. Of the eighteen who had participated in his election in 1334 (and one who had not), eleven had died (besides himself), leaving six. One of these, Cardinal Audemar Roberti of S. Anastasia, had died only six days before the Pope, on December 1, 1352. The number of cardinals eligible to participate in the Conclave of 1352, therefore, was twenty-seven. For a list of all the cardinals from 1294-1378, see Souchon, 163-184: "Beilage I: S.R.E. Cardinales...").

Clement VI had appointed only two Dominicans; Gerard de Daumaria (1342-1343), and Joannes 'de Molendinis' (1350-1353). He had named three Benedictines: Hughes Roger (1342-1363), Guillaume d'Aigrefeuille (1350-1369), and Aegidius Rinaudi (1350-1353). There were two Franciscans: Elias de Nabinalis (1342-1348), and Pasteur de Sarrats (1350-1356). Raymond de Canilhac (1350-1373) and Arnaud de Villemur (1350-1355) were Canons Regular of Saint Augustine. Of these nine, seven were still alive to attend the Conclave of 1352.

Ciaconius-Olduin II, pp. 521-523, provide a list of twenty-eight cardinals who were alive at the time of the election of Innocent VI: six cardinal-bishops, fifteen cardinal-priests; and seven cardinal-deacons. They list "Arnaldus Gallus Presbyter Cardinalis sanctorum duodecim Apostolorum", though they also list Pectin de Montesquieu [Pictainus Gallus] as Presbyter Cardinalis sanctorum duodecim Apostolorum. An impossibility. Arnaud was Cardinal Priest of S. Sisto. They also list "Stephanus de Gardia Gallus, Presbyter Cardinalis: this is probably a doublet for Étienne Aubert, who had been promoted Bishop of Ostia on February 13, 1352. They include Elie de Nabinalis, O.Min., who had died in 1348.

- Pierre de Pratis (des Près), of Cahors [born at the Château de Montpesat], son of Raimond, seigneur de Monpesat, and Aspasie de Montaigut. Suburbicarian Bishop of Palestrina (1323-1361); previously Cardinal Priest of S. Pudenziana (1320-1323). Doctor of civil law. Archdeacon of Rochester [Bliss, Calendar II, 210 (February 9, 1321)]. In 1319 he was made Archbishop of Aix (1318-1321) [Eubel I, 96; cf. Baluze I, 747], previous to which he had briefly been Bishop of Riez (1318) [Eubel I, 417; Gallia christiana I (1716), 320-321 and 404; Gallia christiana novissima: Aix (1899), 79-80 and instrumenta pp. 55-56]. He had earlier been Provost of Clermont, by papal provision. Doctor of Canon Law, Professor at Toulouse. He assisted in the revision of the Statutes of the Fratres Minores [Baronius-Theiner 25, sub anno 1336, no. 65, p. 88]. He was ordered by Innocent VI in 1361 to lead a Crusade, but he died before his mission could be begun [Baronius-Theiner 16, sub anno 1361, no. 5, p. 58]. (died May 16, 1361, pace Eubel). Vice-Chancellor

- Guy de Boulogne, son of Robert VII, Comte d' Auvergne et de Boulogne, and Marie de Flandre, niece of Robert de Bethune, Comte de Nevers et Flandre [Etienne Baluze, Histoire de la maison d' Auvergne (Paris 1708), p. 115-118; and especially 120-129]. Cardinal Guy's niece, Jeanne d' Auvergne, was married to King John of France on September 26, 1349 [Etienne Baluze, p. 114]. He was also a relative of Emperor Charles IV. He was also Uncle of Cardinal Robert of Geneva (1371-1378), Pope Clement VII, 1378-1394 [Etienne Baluze, p. 119-120]. He was Bishop of Porto e Santa Rufina (1350-1373) [Eubel I, p. 19 n. 3], previously Cardinal Priest of S. Cecilia (1342-1350). Archbishop of Lyons (1340-1342). Archdeacon of Flandres. In 1342 he was provided benefices in the Dioceses of Cologne, Trier, and Mainz by Clement VI [H. Sauerland, Urkunden und Regesten zur Geschichte der Rheinland III (Bonn 1905), no. 71 (October 5, 1342)]. He was appointed Legate to the King of Hungary on December 1, 1348 [Baronius-Theiner 25, sub anno 1348, no. 12, p. 443; sub anno 1349, nos. 1-9, p. 457-462], with the mandate to reconcile King Ladislaus and Queen Johanna of Naples. On March 9, 1349, Cardinal Guy, whose Legateship apparently extended over part of Northern Italy as well, took up residence in Padua [Baronius-Theiner 25, sub anno 1349, no. 8, p. 462]. In 1350, he was mandated to participate in the Jubilee; he met Petrarch in Padua in February, 1350, where he presided over the translation of the relics of S. Anthony on February 14, 1350. He then visited Rome. He presided over a synod at Padua on June 20, after his visit to Rome [Baronius-Theiner 25, sub anno 1350, no. 13-14, p. 484; Mansi, Sacrorum conciliorum nova et amplissima collectio 26 (Venice 1784), 221]. His mother, Marie de Flandre, was present in Rome for the Jubilee [Baronius-Theiner 25, sub anno 1350, no. 2, p. 478]. He was one of the Cardinals appointed to examine the disorders in Rome, including the attempted assassination of Cardinal Annibaldo di Ceccano, Legate for the Jubilee of 1350 [Baronius-Theiner 25, sub anno 1350, no. 4, p. 479-480]. In 1352, he was in Avignon, where he provided the blessing for the new Abbot of l'Isle-Barbe near Lyon, Jean Pilfort de Rabastencs, appointed by Clement VI [Etienne Baluze, Histoire de la maison d' Auvergne (Paris 1708), p. 124; Gallia christiana 4, 230 (May 15, 1352)]. Baluze states that the appointment came from Innocent VI, which cannot be correct; Clement VI was still alive until December 6, 1352. Innocent VI was elected pope on December 18, 1352, and crowned on December 30, 1352. Cardinal Guy was provided Dean of S. Martin de Tours on November 12, 1352, and held the office until his death [Gallia christiana 14, 182].

Cardinal Guy, suggested to Clement VI an embassy which he would undertake at his own expense to bring peace between the Kings of England and France. He did not set out, however, due to the death of Pope Clement [Baronius-Theiner 25, sub anno 1352, no. 19, p. 536, derived from a Vatican manuscript, no. 3795]:

Anno Domini MCCCLII, Dominus Boloniensis cardinalis mittitur legatus in Franciam: sed tunc non proficiens, et interim mortuo domino Clemente, post creationem domini Innocentii VI papae reversus Avinionem, satis cito iterum reversus est, pacem reformare cupiens inter reges.

The statement is self-contradictory. It says that Guy was appointed Legate, but did not set out, and in the meantime Pope Clement VI died; after the election of Pope Innocent VI, having returned to Avignon, he returned again shortly thereafter, wishing to restore peace between the kings. Whence did he return to Avignon? Not from France, since he had not set out. If you do not set out you do not return. It seems as though the phrase reversus Avinionem is misplaced or miscast in a badly constructed sentence. Some sort of emendation is required. Baluze noticed this [Histoire de la maison d' Auvergne, p. 124], and stated that Cardinal Guy did not set out until commissioned by the new Pope, and that his journey began at the beginning of 1353. Perhaps reversus Avinionem belongs after Clemente, indicating that he was still in the neighborhood of Avignon, since he had not set out. Or perhaps the clause should read: post creationem domini Innocentii VI papae, profectus Avinione pacem reformare cupiens inter reges, sed satis cito iterum reversus est. Cardinal Guy was in Avignon and did participate in the Conclave of December 16-18, 1352. He was sent to the two kings again by a commission as Legatus on May 30, 1353, which alludes to his earlier mission [Baronius-Theiner 25, sub anno 1353, no.15, pp. 552-553]. - Élie Talleyrand de Périgord, Cardinal Priest of S. Pietro in Vincoli (1331-1348), then Bishop of Albano (1348-1364). Archdeacon of London to 1322, when promoted to Richmond [Bliss, Calendar II, p. 210 (October 20, 1320), p. 231]. Archdeacon of Richmond (1322-1328) [Le Neve, Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae III, 138]. Dean of York (1347-1364) [Bliss, Calendar of Papal Registers 3, 255, 337]. Prebend of Loughton in Morthugg, Diocese of York [Bliss, Calendar III, p. 52 (June 30, 1342)] Canon of Lincoln and Prebend of Thame (from 1335) [Bliss, 518 (July 3, 1335); Le Neve II, 220]. (died January 17, 1364). "Petragoriensis"

- Bertrand de Déaulx, Suburbicarian Bishop of Sabina. He had been legate of Clement VI in Sicily for several years [e.g. Baronius-Theiner 25, sub anno 1348, no. 1-12, pp. 439-443]. Archdeacon of Dorset in 1347 [Jones, Fasti Ecclesiae Sarisberiensis (London 1879), p. 139]. He had been Avignon's principal negotiator with Cola di Rienzi. He was one of the Cardinals appointed to examine the disorders in Rome, including the attempted assassination of Cardinal Annibaldo di Ceccano, Legate for the Jubilee of 1350. (died October 21, 1355) Professor of Civil and Canon Law.

- Guillaume Court, OCist., Suburbicarian Bishop of Frascati (1350-1361). He was one of the Cardinals appointed to examine the disorders in Rome, including the attempted assassination of Cardinal Annibaldo di Ceccano, Legate for the Jubilee of 1350. (died June 12, 1361) Master of Theology. [Cardella II, 152-154]

- Étienne Aubert, of Limoges, Suburbicarian Bishop of Ostia e Velletri (1352), previously Cardinal Priest of SS. Giovanni e Paolo (1342-1352). Doctor Juris Civilis (Doctor Legum), Poenitentarius Major [Baluze I, 286, 321, 345] Petrarch called him magnum virum et juriscunsultissimum. "Magalonensis". He had been Canon of Paris, Bishop of Noyon (1338-1340), Bishop of Clermont (1340-1342). Archdeacon of Cambrai (1342-1352), Archdeacon of Brabant (from 1349 to 1352), Canon and Prebend of Liège (1349-1352) [Ursmer Berlière, OSB, Bulletin de la Commission Royale d' histoire 75 (Bruxelles 1906), 159-160]. Elected Pope Innocent VI (died September 12, 1362).

- Guillaume d'Aure, OSB, Cardinal Priest of S. Stefano al Monte Celio. (died December 3, 1353) Professor of Canon Law [Baluzius I, col. 216; cf. cols. 822-824]

- Hughes Roger, OSB, Cardinal Priest of S. Lorenzo in Damaso. (died October 21, 1363). Brother of Pope Clement VI. "Cardinal de Tulles" "Tutellensis"

- Pierre Bertrand the Younger, of Provence, Cardinal Priest of S. Susanna (died July 13, 1361) Nephew of Cardinal Pierre Bertrand (who had died on June 23, 1348)

- Aegidius (Gil) Álvarez de Albornoz, Hispanus, Cardinal Priest of S. Clemente. Immediately after the election, the new Pope, Innocent VI, sent him off to Italy as Legate [Baronius-Theiner 25, sub anno 1353 no. 1, p. 543-545 (May 30, 1353); A. Theiner, Codex diplomaticus dominii temporalis Sanctae Sedis (Roma 1862) II, no. CXLII-CXLIII, pp. 246-250]. (died August 23, 1367). [Baluzius I, 259, 891]

- Pasteur de Sarrats (Serriscuderio), O.Min., Cardinal Priest of Ss. Marcellino e Pietro (1350-1356). Master of Theology (Paris). Bishop of Assisi (1337-1339). Archbishop of Embrun (1339-1351) [Eubel I, 234; Gallia christiana 3, 1086-1087] Legate to King Philip of France in 1347. (died October 11, 1356) [Baluzius I, 892]

- Raymond de Canilhac, Canon Regular of Saint Augustine, Cardinal Priest of S. Croce in Gerusalemme. (died June 20, 1373). Both of his uncles, Pons and Guy, were abbots of Aniane (Diocese of Maguelonne, 30 km. from Montpellier). His mother was the sister of Cardinal Bertrand de Deaulx. His sister, Dauphine, married Guy III d' Auvergne. His niece, Guerine, married in 1345 Guillaume Roger, the brother of Pierre Roger (Clement VI) [Etienne Baluze, Histoire de la maison d' Auvergne (Paris 1708), p. 195]. Raymond was Canon Regular and Provost of Maguelonne. Archbishop of Toulouse (1345-1350). Nephew of Clement VI.

- Guillaume d'Aigrefeuille, OSB, of Limoges (born ca. 1317), Cardinal Priest of S. Maria in Traspontina (Trans Tiberim) (1350-1368). Archbishop of Zaragoza (1347-1350). Camerarius of the Monastery of Crassensis (Notre Dame de la Grasse) in the diocese of Carcassone [Baluze I, 902, and II, no. 137, p. 694-695; cf. Gallia christiana 6 , 957-958]. Notary Apostolic. "Consanguineus et cubicularius ipsius Papae [Clementis VI]", in whose household he began his ecclesiastical career, when Pierre Roger was Archbishop of Rouen (1330-1338) [Baluzius I, 259, 902-905; Gallia christiana 11, 77-78]. (died October 4, 1369).

- Niccolò Capocci, a Roman, Cardinal Priest of S. Vitale. In 1337, he was Papal Chaplain and Papal Nuncio in Germany [H. Sauerland, Urkunden und Regesten zur Geschichte der Rheinland III (Bonn 1905), no. 1108-1110; 1164]. He was one of the Cardinals appointed to examine the disorders in Rome, including the attempted assassination of Cardinal Annibaldo di Ceccano, Legate for the Jubilee of 1350. (died July 26, 1368) [Baluzius I, 259, 898]

- Pectin de Montesquieu, son of Raymond-Aimeric IV, baron of Montesquieu in Armagnac, and Alpais d'Aussune; a Gascon. Cardinal Priest of Ss. XII Apostoli (1350-1355). Bishop of Albi (1339-1350) [Gallia christiana 1, 27]. Bishop of Maguelonne (1334-1339) [Gallia christiana 6, 782-783]. Bishop of Bazas (1325-1334) [Gallia christiana 1, 1203]. Doctor utriusque iure (died February 1, 1355) [Eubel I, p.19 no. 19]

- Arnaud de Villemur, a Gascon, Canon Regular of Saint Augustine, Cardinal Priest of S. Sisto. (died October 28, 1355) [Baluzius I, 259, 902]

- Pierre de Cros, of Limoges, Cardinal Priest of Ss. Silvestro e Martino ai Monti. Dean of Paris [A. Molinier & A. Lognon, Obituaires de la province de Sens Tome I (Diocese de Sens) (Paris 1902) 230]. Bishop of Senlis (1344-1349). Bishop of Auxerre (1349-1350). Archdeacon of London [Bliss, Calendar of Papal Registers III, 530 (April 27, 1354)]. (died September 23, 1361) [Baluzius I, 259, 900]. Nephew of Clement VI

- Aegidius Rigaudi (Gilles Rigaud), OSB, Cardinal Priest of S. Prassede. (died September 10, 1353). Abbot of Saint Denis. [Baluzius I, 259, 905]

- Joannes 'de Molendinis' (Jean de Moulins), OP, of Limoges, Cardinal Priest of S. Sabina. (died February 23, 1353) [Baluzius I, 259, 906]

- Gaillard de la Mothe, of Bourdos in Gascony, diocese of Aquitaine; son of Amanieu, Baron de la Mothe, Seigneur de Langon et de Rochetaillé, and Alix de Got, the daughter of Clement V's brother, Arnaldus Garsia de Got. Cardinal Deacon of S. Lucia in Silice (1316-1356). (died December 20, 1356). Protonotary Apostolic. Former Canon of Narbonne [Regestum Clementis Papae V, I, no. 211 (July 31, 1305)]. Prebend of Milton Ecclesia in the Church of Lincoln (contested: 1316-1326) [Bliss, Calendar of Papal Registers II, 214-215, 250, 252; Le Neve II, 187]. Archdeacon of Exeter. Archdeacon of Lincoln [Bliss, Calendar of Papal Registers II, 150]. Archdeacon of Oxford (1312—after 1345, perhaps until his death) [Le Neve, Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae II, 65; and cf. Bliss II, 287, 303, 358, 536, 551]. Precentor of Chichester [Le Neve II, 187]. He also had benefices in the dioceses of Canterbury, Winchester, and Paris [Bliss II, 545 (June 12, 1339)]. It should be remembered that his family were vassals of the Kings of England. He assisted in the revision of the Statutes of the Fratres Minores [Baronius-Theiner 25, sub anno 1336, no. 65, p. 88]. Cardinal Gaillard rebuilt the family seat at Rochetaillé [Edouard Feret, Essai sur l' arrondissement de Bazas (Bordeaux 1893) 48-49]. He died November 20, 1356 and was buried in Bazas, where he had erected a monument for his uncle Pope Clement V. An alternative version has it that he was buried in the Cathedral of St. Just in Narbonne on January 15, 1537 [Louis Narbonne, La cathédrale Saint-Just de Narbonne (Narbonne 1901) 146-147]; this obviously refers to the other Gaillard de la Mothe-Preissac. He is commemorated in the Church of Notre Dame de Chartres on January 3 [A. Molinier & A. Lognon, Obituaires de la province de Sens. Tome II (Diocese de Chartres) (Paris 1906) p. 126]. [forgotten by Salvador Miranda]

- Bernard de la Tour d' Auvergne, Cardinal Deacon of S. Eustachio (1342-1361). Rector of Brompton, Diocese of York. provided by Clement VI on April 30, 1343 [Bliss, Calendar of Papal Registers III, 516 (February 15, 1354)]. (died August 7, 1361). His nephew married the niece of Clement VI [Baluzius I, 286, 853].

- Guillaume de la Jugié (Guillelmus Iudicis), of Limoges, Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Cosmedin. (died April 28, 1374). His mother, Guillaumette Rogier, was sister of Clement VI [Baluzius I, 854], He succeeded Cardinal Annibaldo Ceccano in mid-1350 as Legate in Sicily [Baronius-Theiner 25, sub anno 1350, no. 26, p. 489].

- Nicolas de Besse, of Limoges, Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Via Lata. Canon of Paris. Canon and Prebend of Liège (1351-1369). Archdeacon of Condroz in the Diocese of Liège (1344-1369). Rector of the parish of Neerlinter (1351-1369) [Ursmer Berlière, OSB, Bulletin de la Commission Royale d' histoire 75 (Bruxelles 1906), 179-180] (died November 5, 1369). Nephew of Clement VI [Baluzius I, 874]. "Lemovicensis"

- Pierre Roger de Beaufort (aged ca. 21), of Limoges, Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria Nuova (1348-1370). Provided as Archdeacon of Canterbury (1343-1370) [Bliss, Calendar of Papal Registers III, p. 2 (June 25, 1343); p. 263 (November 20, 1347); Le Neve Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae I, 40-41]. (died March 27, 1378). [Baluzius I, 259, 275] Nephew of Clement VI.

- Rinaldo Orsini, a Roman, Cardinal Deacon of S. Adriano. Papal Notary. Canon of Lincoln, Padua, Toledo, Liège, Nassington. Archdeacon of Leicester in the Church of Lincoln. Prebend of Saint-Victor de Corbetta in the Church of Milan (resigned 1323). Archdeacon of Majorca in the Church of Leon (resigned 1324). Archdeacon of Campine in the Church of Liège (1323-1374) [Ursmer Berlière, OSB, Bulletin de la Commission Royale d' histoire 75 (Bruxelles 1906), 168-171] (died June 6, 1374) [Baluzius I, 907]

- Jean de Caraman, of Cahors, son of Arnaud, Vicomte de Caramain; his grandfather was Pierre, the brother of Jacques Duèse (John XXII). Cardinal Deacon of S. Giorgio in Velabro, for ten years, seven months, and several days. Protonotary apostolic. He died of the plague in Avignon on August 1, 1361 [Ciaconius-Olduin II, 517; Baluzius I, 259, 907; Duchesne, Cardinaux françois, 541] Grand-nephew of John XXII, and a complete nonentity.

The Camerarius S. R. E. was Msgr. Etienne Cambarou (Cambaruti), Archbishop of Toulouse (1350-1361). He had previously been Archbishop of Arles (1348-1350), and before that Bishop of St. Pons de Thomières (1346-1348). Before his appointment as Camerlengo in 1347 he had been Treasurer General. [C. Samaran and G. Mollat, La fiscalité pontificale en France au XIVe siècle (Paris 1905), p. 168.]

Dom Jean Birel for Pope?

There is an interesting story, which can be traced to the Cistercian author, Dom Petrus Dorlandus (Pieter Dorland, died 1507) who reports in his chronicle (Martène, 187-188) that the twenty-second General of the Cistercians, Jean Birel (Ioannes Birellius) had been considered for the papal office at the Conclave of 1352:

Ob quam causam cum felicis recordationis Clemens papa sextus viam fuisset universae carnis ingressus, major pars cardinalium ipsum [Ioannem Birellium] in summum pontificem eligere disponebat: quod videns domnus cardinalis Petragoricensis, qui tunc temporis inter cardinales quasi vexillifer habebatur, scilicet praefati prioris electionem ad apicem pontificalem perduci velle: cum sentiret ipsum priorem summae esse justitiae et aequitatis, neque ullum hominem mundi contra justitiam reveri: surgens in medio collegii ait: Domini mei reverendi cardinales, vos quod facitis ignoratis. Sciatis pro certo priorem Carthusiae tantae fore justitiae, rigoris, et aequitatis, quod si ipsum in papam eligimus, pro certo ad statum nos reducet antiquum; atque equi nostri infra quattuor menses quadrigas conducent: non enim cujusquam veretur personam, quia ecclesiam Dei zelans, quasi leo confidit. Quo audito, domini cardinales perterriti, sibique ipsis nimis carnaliter metuentes, praefato priore praetermisso, dominum Innocemtium sextum de collegio suo elegerunt....

When Clement VI had died, the majority of cardinals was disposed to elect Jean Birel as pope. But seeing that Cardinal Talleyrand de Perigord was then the leader among the cardinals, and that he wished to prevent Birel being elected, for he saw that he was a Prior of outstanding justice and equity, he got up in the midst of the college of cardinals and said, "My lords, reverend cardinals, you don't know what you are doing. You are aware for certain that the Prior of Chartaux will be a man of such justice, rigor and equity, that if we elect him as pope, he will certainly bring us back to our ancient state; and inside of four months, our horses will be pulling quadrigae: for he is not afraid of the status of any one, because he is like a lion in his zeal for the Church of God." When the cardinals heard this, they were thoroughly frightened, and fearing too much for their material comforts, they passed over the Prior, and elected Pope Innocent VI from their own College....

And, later in the story, after the news of the death of Jean Birel is brought to Avignon (Martène, 192-193):

Dum vero Avenioni rumor de transitu prioris Cartusiae percrebuisset, domnus Innocentius papa adhuc superstes, haec audiens, in vocem lacrymanum, ut fertur, prorupit dicens: Valentior religiosus et clericus mundi mortuus est. Cum vero post modicum tempus supradictus papa in extremis laborasset, et finem suum adesse cerneret, coram infinitis astantantibus intonuit dicens: Utinam anima mea esset coram Deo talis qualem aestimo fore animam Johannis quondam prioris Carthusiae. Praescriptus etiam dominus cardinalis Petragoricensis, qui ejusdem prioris electionem in papatu impediverat, audita ejus morte, in haec verba prorupit: Vae nobis, quia tristes nos. Tristis est ecclesia Dei, quia collegium nostrum et ecclesia sancta Dei talem non promeruit habere pastorem. Non enim digni sumus tanto pastore.

There is also an influential sixteenth-century French translation (Driscart, pp. 116-117):

Voicy maintenant que nous avons a parler du R(everend). et saincte Pere Iean Birellios, lequel tant pour sa douceur que pour sa sainctete s' estoit rendu agreable a Dieu et aux hommes, sa renommee et auctorite estant si grande, qu' apres la mort de Clement sixieme la plus grande partie des Cardinaux estoit portee pour l'elire au Pontificat; ce qu' il eut refussi; ne fut este le Cardinal Pertragoricus, qui sçachant le zele et la justice de ce sainct personnage, harasigua ses Confreres les Cardinaux en ces termes: le ne sçay que trop mes Seigneurs que desirez pour notre souverain Pontife la personne du General des Chartreux et certes il faut que se conforse qu' il est tres digne et capable de cet honneur: mais parte que nous autres Joannes ambitieux desir faste, gloire et vanite e de ce monde; et a en horreur touts les attiratis, sottises, et vanitez; d' ecelay, s' il est eleu, sans faute (puis qu' il est porte pour l' equite et la justice) il nous voudra remettre a nostre premier estat, se moquant de nos montures si bien harnacees, et se riant de nos chevaux di superbement accommpdez, dieu nos housses pour lors et nos esperons donees, apres peu de jours il les renuoyera aux champs, et les employera a tirer la charue, car il ne se soucie de personne tant soit-elle puissante ou noble: mais pour l'Eglise il se comporte en guise de Lion fort et courageux. Cecy donna tant de crainte et d'emotion aux Cardinaux que ne luy osant fier leur voix, ils la donnerent a celui qui fut nomme Innocent sixieme...

and, ten years later in the life of Birel by Peter Dorlandus, following the death of Dom Jean Birel in fact (Driscart, 121):

Le Pape Innocent ayant entendu les nouvelles de sa mort dit en pleurant, helas le plus Sainct Religieux et le plus scavant du monde est mort ce joour-d'huy. Le mesme Sainct Pere estant aux abois de la mort disoit en la presence des assistans: A la mienne volente que mon ame parut si innocent devant Dieu que l' ame de ce bon Pere Ian, laquelle je crois avoir une conjour tres-agreable a nostre Seigneur.

Le Cardinal Petragoricensis fut si esterangement émeu de cette mort, que se repentant d' avoir esté cause qu'il n'avoit esté eleir Pape, dit ces mots avec grand regret, Mal-heur a nous Cardinaux, mal-heur à toute l'Eglise qui n'avons voulu avoir vu tel Pasteur, je l' ai defendu et voy la pourquoy mal-heur à moy parce que j' ay fait tort a nous tous, et grandement avit à la Saincte Eglise. Apres sa mort ce bon Pere n' a manqué de miracles, car Lemonicenses, d'ou il estoit natif, ayants recors a son affirtance trouvoient leurs malades aydez et soulangez, raison pourquoy ils envoyerent à la Chartreuse pour avoir quelques Reliques...

Now it is true that the Talleyrand family were noted supporters of the Carthusians. Cardinal Élie's brother, Count Archambaud III, in fact had founded the Chartreuse of Vauclere, and had left it 12,000 gold florins in his Will. But this story of Dom Jean Birel is not in the nature of a "chronicle". Birel had been an advisor of Benedict XI, and his austere, monkish, reformist Cistercian views were well known to all the members of the Sacred College. Birel was, as many leaders of religious orders in the history of the Church, a candidate for sainthood, being promoted by all the prayers and works of the members of his Order. All of the lives of the Carthusian leaders in Dorlandus' work are accompanied by reports of miracles and observations about their morals and moral influence. The anecdote about the Conclave of 1352 originates as part of a work, written in the late fifteenth century, which is at least partially hagiographic in nature, despite its title of chronicle. The anecdote appears nowhere else in extant literature but in the work of the Cistercian Dom Petrus Dorlandus (except by endless repetition). (see Zacour, passim) (Souchon, 54-56).

Piatti has his doubts as to the authenticity of Dorlandus' story (Storia, 106): "Se non che questi scrisse la propria Cronaca circa l' anno 1500, e per conseguente può non essere del tutto giuridica ed accertata la di lui asserzione, se non anco appassionata." Pélissier (Innocent VI, p. 43), though he accepts the tale of Jean Birel, remarks, "le candidature de Jean Birel ne fut pas posée." And his careful language is quite correct. Birel was not put forward as a candidate in the Conclave of 1352. The real interest of the Cardinals was not in the election of a saintly man, or of a man bent on reform. Quite the contrary, their work on a lengthy set of Electoral Capitulations indicates that the issue was power, and how it should be apportioned. Their interest was in limiting the Pope's power over them, rather than in allowing a Pope to reform them without their consent.

Conclave

Pope Clement VI had considerably altered the regulations promulgated by Pope Gregory X at the Second Council of Lyons ("Prima Vita Clementis VI", in Baluzius I, 260-261):

Praefatus insuper Papa laxavit seu verius mutavit constitutionem Gregorii Papae X Ubi majus, de elect. lib VI editam super illis quae Cardinales habent observare quando sunt inclusi in conclavi pro electione Romani Pontificis celebranda. Voluit enim, constituit, et ordinavit quod dicti Cardinales possint a cetero in dicto conclavi existentes habere cortinas, cum quibus claudantur eorum logiae quando dormient seu quiescent. Item quod habeant duos servitores clericos vel laicos, prout eis magis placebit. Item quod elapsis tribus diebus post suum introitum haberent ultra panem et vinum fructus, caseum et electuaria, et unum ferculum carnium vel piscium duntaxat in prandio, et aliud in coena. Super quibus edidit constitutionem perpetuo duraturam, quae incipit Licet; cujus contrarium, quad praedicta, continebat caput praedictum Ubi majus, quod quoad alia omnia voluit in sua remanere firmitate.

There were to be curtains to give Cardinals privacy during sleep or rest. They could have two conclavisti, clerical or lay, as they pleased. After three days, in addition to bread and wine, they were allowed to have fruit, cheese and citrus (?), and one plate of meat or fish, both at lunch and at dinner.

The text of the Bull Licet in constitutione is given in Cherubini, Magnum Bullarium Romanum, p. 179 (dated 8 Idus Decemb, December 6, Pont nostri ann. X), and by Rinaldi [Baronius-Theiner 25, sub anno 1351, no. 39, p. 524].

Twenty-eight cells were built in the Conclave [Deprez, 240 and n. 2], leading some to conclude—erroneously—that there were twenty-eight living cardinals. Thirty-three doorways were walled shut, and sixteen windows.

Electoral Capitulations

There were Electoral Capitulations (André, 351-354; Souchon, 55-66). They are quoted by the successful candidate, Pope Innocent VI, in a letter written in 1352 at the beginning of his reign (Baronius-Theiner, sub anno 1352, nos. 25 and 26, p. 540):

- In deliberations for the public good, the Cardinals must agree unanimously.

- At no time and no matter what the excuse, may the Pope create cardinals without following specific rules (which are then listed):

- The Pope may not create new cardinals until the number of living cardinals has fallen below sixteen.

- When the number has fallen below sixteen, and new cardinals are created, the total number may not exceed twenty.

- In creating new cardinals, the Pope must have the consent of at least two-thirds of the existing cardinals.

- Except that, in the case of their being the number of cardinals now existing or fewer, the Pope, if he wishes, may appoint two cardinals, with the consent of all the Cardinals or the major part of them (i.e., at the present moment, the Pope may appoint two new cardinals with only a majority of Cardinals agreeing)

- The Pope may not proceed to the deposition or the deprivation of any cardinal without consultation and the agreement of all the cardinals with no objections, nor may he inflict any excommunication or other ecclesiastical censure, leading to the loss of a cardinal's vote or share in income, nor deprivation or suspension of benifices of a cardinal without the agreement of all the cardinals, or at least two-thirds of them.

- The Pope may not in any way put his hands on the property of any cardinals, whether they are living or deceassed.

- The Pope may not alienate provinces, cities, castles or other lands of the Roman Church, nor may he grant them under feudal terms or emphitheosis, or under a certain payment. And when such alienation or concession might take place for a just and reasonable cause, the Pope must have the consent of all the Cardinals, or at least two-thirds of them.

- The College of Cardinals ought to have its fair share of all fruits, returns, proventus, fines, condemnations and rents, and of all other income and emoluments, in whatever provinces and lands and places of the Roman Church—just as in the Privilege of the late Pope Nicholas IV.

- In the Roman Curia and in the provinces of the Roman Church, major officials in termporal affairs should be appointed and dismissed with the advice and consent of the Cardinals—just as is recognized in the Privilege (or Constitution) of the aforesaid Pope Nicholas IV.

- No person may be appointed to the offices of Marshal of the Roman Curia or Rector of one of the lands or provinces of the Roman Church who is related to the current pope by consanguinity or affinity.

- The Pope may not grant to any king or prince or anyone else in provincial governments or their lands the decimae (10% of church income), nor third-decimae nor any other subsidy, nor shall the Pope even reserve it for his treasury (Camera) without the advice and consent of all the Cardinals or at least two-thirds of them, and then for just and reasonable cause.

- The Pope shall not impede the Cardinals from having freedom of action as a group or as individuals in taking counsel and in giving their consent.

- All the Cardinals who now exist should swear an oath that he who is elected by the same Cardinals will observe these provisions diligently and inviolabily; and nonetheless he who is elected, whether a cardinal or some other, shall agree on the day of his election to observe faithfully all these provisions generally and individually, and shall do so by oath.

These Capitulations were annulled by Innocent VI on July 6, 1353 in the Bull Solicitudo pastoris (Souchon, 63).

The Conclave of 1352 did not, as events transpired, need to invoke many of the new Conclave regulations promulgated by Clement VI. The Conclave opened on Sunday, December 16 (Deprez, 240), and came to a successful conclusion on Tuesday, December 18 ("Secunda Vita Innocentii VI", Baluzius I, column 345 and 846):

Mortuo Domino Clemente in die Sancti Nicolai, Cardinales intrarunt conclave Dominica post Luciae, et die Martis proxima hunc [Stephanum Alberti] elegerunt.

The Conclave was held in the Apostolic Palace in Avignon, where Clement VI had died. This is referred to by the new Pope, Innocent VI, in his Election Manifesto, Praedicator egregius (Baronius-Theiner, sub anno 1352, no. 28; p. 541):

Nuper siquidem felicis recordationis Clemente papa VI, praedecessore nostro, tela vitae succisa, in Domino quiescente, et ipsius funeralibus exsequiis cum honorificentia debita celebratis, nobisque una cum fratribus nostris S. R. E. cardinalibus, de quorum numero tunc eramus, tempore debito convenientibus invicem in palatio Apostolico Avinionensi, in quo idem praedecessor tempore sui obitus habitabit, pro futuri electione pastoris...

The election was a quick one. The Cardinals had heard that the King of France, John II "The Good", was on his way to Avignon with the intention of getting the Cardinals to elect the person most suitable to his own interests (Matteo Villani, Book III, chapter 45; Baronius-Theiner, sub anno 1352, no. 27; p. 541).

Dopo la morte di papa Clemente sesto, i cardinali rinchiusi in conclave sentendo che il re di Francia s'affrettava di venire a Avignone per avere papa a sua volontà. la qual cosa non gli potea mancare, tanti cardinali aveva a sua stanza e di suo reame, ma non ostante che tutto il collegio de'cardinali fosse stato al servigio del detto re, tuttavia per la riverenza della libertà di santa Chiesa, vollono innanzi avere fatto papa di loro movimento, che a stanza del re di Francia. E però di presente presono accordo tra loro, ed elessono a papa il cardinale d'Ostia nativo di Limogi, il quale era stato vescovo di Chairamonte, uomo di buona vita, e di non grande scienza, e assai amico del re di Francia; la sua fama infra gli altri era di semplice e buona vita, e antico d' età....

The "Third Life" adds that the election took place at the hour of Tierce—mid-morning ("Secunda Vita Innocentii VI", Baluzius I, column 357):

electus est in Papam per Cardinales anno Domini MCCCLII die Martis XVIII Decembris, hora tertiarum

Coronation of Innocent VI

Innocent VI (Étienne Aubert) was crowned in the Apostolic Palace at Avignon on Sunday, December 30 ("Secunda Vita Innocentii VI", Baluzius I, column 345; "Tertia Vita", column 357):

Qui coronatus fuit in palatio Apostolico Avinionensi dominica die infra octabas nativitatis Domini.

et coronatus Dominica penultima dicti mensis Avinione in apostolico palatio.