SEDE VACANTE 1287-1288

April 3, 1287 —February 22, 1288

Death of Honorius IV

The sources agree that Honorius IV (Giacomo Savelli) suffered from podaegra or gutta (gout), as did his brother, but in both cases the condition seems so severe that Pandolf could not get around except on crutches, and Honorius was unable to walk or even move his fingers together, except for his thumb. He had to sit while celebrating Mass, and had a special chair constructed so that, when it was time to elevate the Host, he could be turned around to the people without moving his body. The symptoms seem to be more those of severe arthritis. Nonetheless, both he and his brother were clear in mind and firm in purpose. Honorius died on April 3, 1287, Holy Thursday, after twenty-three months of rule. He was buried on Holy Saturday in St. Peter's Basilica, next to Nicholas III (Raynaldus, ad annum 1287 ix, citing a ms. source).

Of him Giovanni Villani (Book VII, cap. cxii; coll. 317-318) says:

Nelli anni di Christo 1287, a dì 3 d'Aprilo morì Papa Honorio là fu sepelito a grande honore. Questo Papa sostenne anzi parte Ghibellina che Guelfa, & poco adjuto o niente diede all' herede del Re Carlo alla guerra di Cilicia, onde molto montò lo stato e potere del Re Giacomo d' Araona, che se ne havea fatto coronare Re, & tutta parte Ghibellina d' Italia n'essaltò....

Honorius IV named only one cardinal, on December 22, 1285: Giovanni Boccamati (Boccamazza), who became Suburbicarian Bishop of Tusculum. He was a Roman and an adfinis of the pope. He had been made Archbishop of Monreale by Pope Nicholas III in 1278. He died in 1309. (Panvinio, 184; Eubel I, pp. 11, 38,and 348). (Cardella II, 27-28).

The Electors

.At the time of Pope Honorius' death, there were sixteen cardinals (Eubel Hierarchia Catholica I second edition [1913], 10 n. 11). Panvinio (pp. 183-184). In accordance with the Constitution of Gregory X, the Cardinals assembled at the deceased Pope's residence near Santa Sabina. An alternate version, which can be traced back to Abbot Trithemius in his Chronica (Hirslaugiensis), has it that the election took place in Perugia (Antonius Felix Mattheus in his edition of Hieronymus Rubeus' Life of Nicholas IV, p. 17 n.1). That locality cannot be made to agree with the story that the Cardinals had personally pressured Cardinal Girolamo Masci to accept the Papacy in part because Girolamo had stayed in Rome while everyone else had fled.

- Latino Frangipani Malabranca, OP [Romanus] (son of Angelo Malabranca; Nicholas III's nephew by his sister Mabilia Orsini. She was sister of the Matteo Rosso Orsini 'di Montegiordano', who was Roman Senator in 1279), Cardinal Bishop of Ostia and Velletri. He had been deputed by Nicholas to manage the elections for Senator in August, 1278 (Kaltenbrunner, Actenstücke 120; Posse 916), and then, in September, been appointed Legate for Tuscany and the Romagna [ Actenstücke 131; Posse 931; his instructions: Actenstücke 145], a post which he exercised throughout the reign. In October 1278, he arranged peace in Florence and the Romandiola [Giovanni Villani Cronica VII. lvi]. But it is reported that he fled in the wake of the earthquake of May 1, 1279, which was centered in the neighborhood of Ancona [Fra Salimbene, Chronica p. 273-274 ed. Parma 1857]. Bologna and the people of the Romandiola were frightened into making a peace, arranged by Cardinal Latino [Potthast 21588 (May 29, 1279)]. He also excommunicated the people of Parma for turning on the Dominicans in the city because they burned a woman at the stake [Fra Salimbene, Chronica p. 273-274 ed. Parma 1857]. He died on August 9, 1294 ["Note Necrologiche di S. Sabina," in P. Egidi, Necrologie e libri affini della provincia Romana (Roma 1908), p. 296; Santa Sabina was a Dominican convent].

- Bentivenga de Bentivengis, OFM [Acquasparta, Tudertinus (Todi)], Cardinal Bishop of Albano. In 1264 he was personal chaplain of Cardinal Stephen Bancsa, Bishop of Palestrina [Eubel, "Registerband", p. 3—though Eubel believed at the time that Cardinal Stephen had died in 1266, rather than 1271]. He had then been a chaplain and an "intimus amicus" (according to Fra Salimbene) of Cardinal Johannes Orsini, a fellow Franciscan, who became Nicholas III (This could have been between 1271 and 1276). On December 18, 1276, he was named Bishop of Todi [Eubel Hierarchia p. 501 and n. 2]. He was created Cardinal Bishop of Albano on March 12 or 13, 1278. Major Penitentiary [Cardella II, p. 13; though this seems to have been only a special appointment: Sägmüller, Die Thätigkeit, p. 107. The cardinalatial office of Major Penitentiarius as such may have not yet existed. Eubel ("Der Registerband", p. 20) quotes an entry in the register: "Memorandum, quod sanctissimus pater dominus Nicolaus, summus pontifex, mandavit venerabili B. Alban. episcopo Viterbii in camera sua, ut usque ad festum dominicae Resurrectionis proximae futurae adsisteret et iuvaret poenitentiarios in his, quae essent cum ipso domino expedienda contingentia officium poenitentiariae." (September 26, 1279)]. He continued to function as Penitentiary during the Sede Vacante of 1280-1281, and his powers were renewed under Martin IV [Eubel, "Der Registerband", p. 21 (March 3, 1281)]. On November 5, 1285, he was ordered by Pope Honorius IV to visit the Monasterium Lesatense, OSB, in the Diocese of Toulouse personally, and to reform it, because of the crimina et defectus of its Abbot Aculeius [Registres d' Honorius IV, no. 171, pp. 131-132; Gallia christiana 13, 204-206, 212]. Cardinal Bentivenga records issuing a decree on August 10, 1286 [Eubel, "Der Registerband", p. 58 no. 51], and in 1287 during the Sede Vacante, on May 14, at Santa Sabina, the site of the Conclave [Eubel, "Der Registerband", p.63 no. 57], and finally on March 16, 1288 at St. Peter's [Eubel, "Der Registerband", p.65 no. 61]. Nicholas IV granted him in commendam the titulus of SS. Giovanni e Paolo [Potthast 22700 (May 4, 1288)]. Magister in Theologia. Fra Salimbene calls him Frater Beneceven (sub anno 1277, p. 272). He died at Todi on March 25, 1289 [it was actually 1290: see "Chronica Generalium Ministrorum" in Analecta Franciscana III (1897), p. 369 n. 6 and 420].

- Girolamo Masci d' Ascoli, OFM [Lisciano, near Ascoli], Suburbicarian Bishop of Palestrina (from 1281). Former Cardinal Priest of Santa Pudenziana. . Former Minister General of the Franciscans (1274-1279) [Fra Salimbene, sub anno 1277, p. 272]. He was the associate of John of Vercellae, OP, sent to arrange a peace between Philip of France and Alfonso of Spain on October 15 [Potthast 21165; and see Baronius-Theiner 22, sub anno 1277, no. 47, p. 402]. He and John were again appointed to the same task on April 4, 1278 [Potthast 21294-21295; 21310]. Girolamo was ordered to continue on as Minister General of the Franciscans until otherwise provided [Potthast 21356]. On May 16, 1279, Pope Nicholas III wrote to the General Chapter of the Franciscans, meeting at Assisi, that Cardinal Girolamo could not attend propter corporis infirmitatem [Potthast 21582]. In 1283 he and Cardinal Giacomo Colonna were sent as legates to the Romagna to compose the differences between Guelfs and Ghibellines. Doctor in Theology (Perugia). (future Pope Nicholas IV, 1288-died April 4, 1292).

- Bernard de Languissel, Suburbicarian Bishop of Porto. Legate in northern Italy. On June 17, 1283, Cardinal Bernard was named Legate in Lombardy, the Veneto, the Romandiola and Tuscia [Potthst 22038-22040]. He was made protector of the Heremiti S. Augustini on June 30, 1288 [Registres de Nicolas IV, I, no. 170, p. 27] (died September 19, 1291)

- Hugh of Evesham, Cardinal Priest of S. Lorenzo in Lucina. A physician [Marini, Degli archiatri pontifici I, p. 27. According to the manuscript of John Bale's mid-16th century Index Britanniae Scriptorum [Anecdota Oxoniensia 9 (Oxford 1902), pp. 170 (edited by Reginald Lane Poole)], he was a Doctor of Medicine and the author of Quaestiones on Isaac's liber febrium. In 1269, Master Hugh of Evesham was one of the professors at Oxford who became drawn into the controversy between the Dominicans and Franciscans [A. Little, The Grey Friars at Oxford (Oxford 1892), Appendix C, pp. 76-77 and 331, 333]. Rector of Welton and Hemingbrough in the Diocese of York, appointed by Archbishop Giffard (1266-1279) [Register of Walter Giffard, Archbishop of York , 56, 57]. Archdeacon of Worcester in 1275 [Le Neve, Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae III, p. 74; the appointment was made by Bishop Godfrey Giffard (1268-1302), brother of Archbishop Walter Gifford of York].

He is the "Magister Hugo de Ewesan", canon of York, who was present at the election of William Wickwane, Chancellor of York, as Archbishop of York, on June 22, 1279. Chancellor William voted for Hugh [Registres de Nicolas III, 559; Bliss, Calendar of Papal Registers I, p. 459; Le Neve Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae III, p. 103].

Canon Hugh was granted the Prebendary of Bugthorpe in the Church of York, by November 11, 1279 [J. Le Neve, Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicani III, p. 178]. On December 17, 1279, Master Hugh of Evesham, Canon of York, was one of the examiners of candidates for ordination in the Diocese of York, on appointment of Archbishop Wickwane [The Register of William Wickwane, p. 22]. He was called to Rome, due to his medical skills, it is said, by Nicholas III. On September 12, 1280, Archbishop Wickwane named Master Hugh of Evesham, Canon of York, and Stephen Patringtone his proctors at the Papal Curia, and so notified Cardinal Matteo Rosso Orsini and Cardinal Giacomo Savelli [The Register of William Wickwane, p. 183].

On April 12, 1281, Hugh of Evesham was named a cardinal. Archbishop Wickwane sent him a joyous letter of congratulations, and a warning to keep certain kinds of activities out of his house. On April 13, 1282, Cardinal Hugh's chaplain was named Bishop of Caithness by provision of Martin IV [Bliss, Calendar of Papal Registers I, p. 464]. Cardinal Hugh had a relative (consanguineus), Richard of Duiard, for whom he procured a canonry at the Cathedral of Lichfield [Registres d' Honorius IV, no. 342, p. 253 (February 23, 1286)]. He died on July 27, 1287, Sede Vacante, the Sunday after the Feast of St. James. [Register of Bishop Godfrey Gifford II, p. 333]. It is alleged in the Annales Wigorniae [Annales Monastici IV ed. Luard, pp. 493-494] that he was poisoned; quidam pestilentes venenum vino miscuerunt; quo potu magister Hugo de Evesham cardinalis sexto kal. Augusti vitam finivit temporalem. - Gervasius Giancolet de Glincamp (Gervasius de Clinio Campo) [diocese of Mans, Cenomanensis], son of Gervais, great-grandson of Eudes, chevalier and seigneur de Groestel [Roy, Nouvelle histoire des cardinaux françois, IV, 2]. Cardinal Priest of S. Martino in Monte, tit. Equitii. Doctor of Theology (Paris). Formerly Archdeacon of Le Mans [Denifle, Chartularium Universitatis Parisiensis I, no. 490 (August 5, 1279), p. 575; no. 493 (October 19, 1279), p. 577], Archdeacon of Paris [Duchesne, Cardinaux françois, p. 303], or Dean of Paris [du Boulay, Historia Universitatis Parisiensis III, p. 680; this is rejected by Roy, p. 3]. On September 7, 1283, he was sent along with Cardinal Masci to persuade the troops of Viterbo and of Bertoldo and Urso Orsini to withdraw from Church territory [Registres de Martin IV, no. 474-476, p. 217-218]. He died on September 24, 1287 [Eubel, Hierarchia catholica I, p. 8]. The Church of Paris, however, commemorated him on September 16 [Guérard, Cartulaire de Notre Dame de Paris IV (1850), 148]. Roy [p. 6] says that the Obituary of the Church of Paris commemorates him on October 22. The Martyrology of S. Victor commemorates him on September 21. The Church of Le Mans commemorated him on September 15.

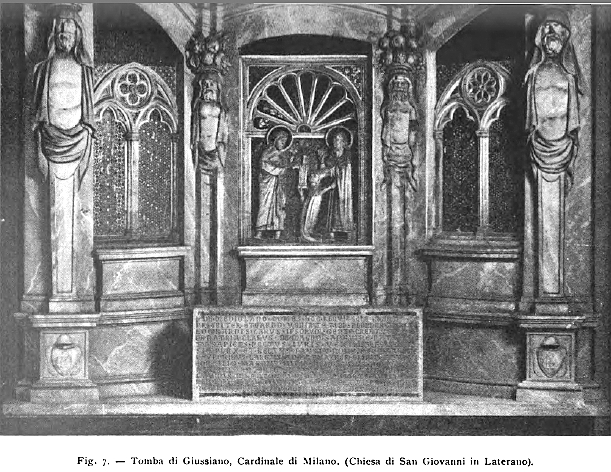

- ? Comes [Conte Casate; Glusiano Casati], Cardinal Priest of Ss. Marcellino e Pietro (1281-1287). Former Archdeacon of Milan. Auditor of the Rota under Nicholas III. He was employed principally in the examination of elections of bishops-elect and abbots-elect, and Auditor in appeals. (dead by April 8, 1287, Sede Vacante: Rohault, Le Latran, p. 175).

- Gaufridus (Geoffroy) de Barro or Barbeau, of Burgundy, Cardinal Priest of S. Susanna, formerly Dean of the Church of S. Quentin en Vermandois [Roy, p.1, 5, and 23; in 1268], Chaplain of the Bishop of Paris (according to Duchesne; Roy, 5-8, 21, in 1263) On September 29, 1270, as Canon of Paris, he was named heir of Robert de Sorbon, Canon of Paris, in his Will. In November, 1274, when he was Dean of the Cathedral of Paris, he in turn gave all the property he inherited from Robert de Sorbon to the Congregatio pauperum Magistrorum Parisius studentium in Theologica Facultate [Luca d' Achery, Veterum aliquot scriptorum Spicilegium IX (Paris 1668), 247-248 and 249]. His Deanship is also mentioned by Martin IV [Registres de Martin IV, no. 384, p. 157]. He was created cardinal on Holy Saturday, April 12, 1281. He served as papal Auditor in examination of episcopal and abbatial elections. On April 30, 1283, he was granted control over the Hospice of S. Andrew next to S. Maria Maggiore [Registres de Martin IV, no. 324, p. 139]. He died in 1287, Sede Vacante. Ciaconius-Olduin (II, 243) states that he is commemorated in the Necrologium Ecclesiae Parisiensis on August 21; however, in the Obituarium of the Church of Paris on August 21, the commemoration is that of Geoffrey, Count of Brittany, son of King Henry II of England [Guérard, Cartulaire de Notre Dame de Paris IV (1850), 133]. The Abbey of S. Victor commemorates him on September 19.

- Godefridus (Gottifridus, Geoffroy, Gottifredo di Raynaldo da Alatri, Goffredo di Alatri in Lazio), son of Galgano of the Lords of Scurocola [according to Gregorovius V, 68]. Cardinal Deacon of S. Giorgio in Velabro (1261-1287). Canon of the Cathedral of Alatri (by 1229). In 1251 he is mentioned as a chaplain of Cardinal Stefano de Normandis of the titulus of S. Maria in Trastevere, and granted the privilege of being Decanus Olensis and pastor of the church of S. Stefano in Alatri at the same time [Registres d' Innocent IV, Tome III, no. 5462, p. 5]. Chaplain of Alexander IV and judge in a case between the Bishop of Ascoli and a certain Rinaldo [G. Mazzatinti, Gli archivi della storia d' Italia III (Rocca S. Casciano 1900-1901), p. 96 (Ascoli, Archivio capitolare, 1257)]. He countersigned two letters of Nicholas III [Registres de Nicolas III no. 458 and 459 and 475 (St Peter's, March 18, 1279; May 7, 1279)]. He signed a bull for Nicholas III, regulating the statutes of the clergy of St. Peter's Basilica [Registres de Nicolas III no. 517 (February 3, 1279)]. In February, 1281, before a coronation could be arranged for Martin IV, he and Cardinal Latino Malabranca Orsini were sent to Rome 'velut pacis angelis'. The mission was a failure [Martène-Durand, Veterum scriptorum II, 1284-1285; Potthast 21738] † 1287 (cf. Sternfeld, 289 n.3); an inventory of his possessions was taken on May 31, 1287. [Cardella I. 2, p. 302-303, records no achievements except that he was a cardinal for twenty-six years, and crowned Pope Honorius IV]. [He possessed fifty-two books at his death, of which twenty-three were juridical in nature: M. Prou, "Inventaire des meubles du Cardinal Geoffroy d' Alatri (1287)," Melanges d' archeologie et d' histoire 5 (1885), 382 ff.; a list of the books in: Neuer Anzeiger für Bibliographie und Bibliothekwissenschaft 47 (1886), pp. 105-107].

- Matteo Rosso Orsini, [Romanus], grandson of Matteo Rosso “il Grande” (born 1178, died October 13, 1246), son of Gentile Orsini, Signore di Mugnano, Penna, Nettuno e Pitigliano e Nobile Romano; nephew of Gian Gaetano Orsini (elected Nicholas III). Cardinal Deacon of Santa Maria in Porticu (1262-1305). He became Archpriest of the Vatican Basilica under Nicholas III, before May 25, 1278 [Huyskens, Historisches Jahrbuch 27 (1906) 266 n.1; Registres de Nicolas III no. 517 (February 3, 1279)]. Made a Prebend of Lincoln by Nicholas IV [Potthast 22679 (April 25, 1288); Registres de Nicolas IV, III, no. 7407, p. 1022]. On May 7, 1288, Nicholas IV confirmed his position as Protector of the Franciscans, which he had held since 1279 [Potthast 22703]. (died September 4, 1305).

- Giordano Orsini, Cardinal Deacon of S. Eustachio. (died 1287). Brother of Pope Nicholas III

- Giacomo Colonna [Romanus], son of Giordano Colonna, Signore di Colonna, Monteporzio, Zagarolo, Gallicano e Palestrina; and Francesca, daughter of Paolo Conti. Brother of Giovanni Colonna, Senatore di Roma, 1279-1280. Uncle of Cardinal Pietro Colonna and Stefano Colonna. Archdeacon of Pisa. Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Via Lata (March 12, 1278; deposed May 10, 1297; restored February 2, 1306). Archpriest of the Liberian Basilica [Archivio della Società romana di storia patria 30 (1907), no. 79-81, p. 133-134 (July 30, 1288; August 11, 1288)]. (died August 14, 1318 in Avignon.)

- Benedetto Caetani, seniore, a Campanian from Agnani; his mother was a Conti, the niece of Pope Alexander IV. Cardinal Deacon of S. Nicolae in Carcere Tulliano, from April 12, 1281. Canon of the Vatican Basilica [Archivio della societa romana di storia patria 6 (1883), 11]. Legate of Martin IV to Charles I of Sicily (1282) to dissuade him from war against King Pedro of Aragon. Legate in south Italy. In February, 1283, he was sent to Charles of Sicily again, to attempt to resolve the situation [Baronius-Theiner 22, sub anno 1283 no. 8-13; Potthast 21981]. Benedetto was given the titulus of SS. IV Coronatorum [Salvador Miranda gives the date of April 1, 1285, but that was during the Sede Vacante, the day before the election of Urban IV]; the correct date is April 11, 1283, and the pope was Honorius IV [Registres d' Honorius IV, no. 826, p. 586]. (died October 11, 1303).

- Gerardo Bianchi [Gainaco, diocese of Parma], Cardinal Priest of Santi XII Apostoli, Cardinal Bishop of Sabina on March 23 or April 12, 1281. d. 1302. Doctor in laws (Parma). Protonotary Apostolic. He was legate in Sicily at the time of the death of King Charles I (January 7, 1285), and was appointed administrator [Regni Ballius], along with Count Robert of Artois (Arras). Fra Salimbene of Parma speaks of him sub anno 1282 ( p. 281) as Legate in Sicily at the time of the Sicilian Vespers (1282). Legate and Regent in Sicily. He was still Legate and Regent under Honorius IV [Potthast 22499 (July 15, 1286)]. He was still Legate and Regent on April 1, 1288, under the new Pope, Nicolaus IV [Potthast 22630] His Constitutiones from his Legateship are to be found in Codex Palatinus Latinus 637, at f. 106v. [Stevenson and De Rossi (editors), Codices Palatini Latini I (Romae 1886), p. 227] (died March 1, 1302).

- Giovanni Boccamati (Boccamazza) [Romanus], a relative of Pope Honorius IV. Suburbicarian Bishop of Tusculum (Frascati). Chaplain of Pope Nicholas III. Archbishop of Monreale and Administrator of Monreale (1278-1286) [R. Pirro, Sicilia sacra I (Panormi 1733), 463], by appointment of Nicholas III [Registres de Nicolas III, no. 120, pp. 38-39]. Legate in Germany, 1287. It was Cardinal Boccamazza who delivered the news of the Sicilian Vespers to King Charles I [V. D'Avino, Cenni storici sulle chiese arcivescovili, vescovili e prelatizie (nullius) del Regno delle Due Sicilie (Napoli 1848), 359]. Former Legate in Germany, Bohemia and Hungary, May 31,1286, with powers to absolve former supporters of Conrad and Conradin [Potthast 22498 ((June 14, 1286); Eubel, Hierarchia catholica I, p. 11 n.2]. On July 22, 1287, during the Sede Vacante, he was at Cambrai, where he issued orders for Dacia and Suecia [Potthast 22598]. On September 21, 1287, he was at Clairvaux [Potthast 22599], and he was still there on November 8, when he wrote to the Archbishop of Uppsala, Sweden (Suecia) [Potthast 22601], and December 6, 1287, when he wrote to the Dominicans of Hungary and Poland [Potthast 22602]. He wrote from Novaevallis on December 14, to all of the clergy in his Legation for the benefit of the Cistercians [Potthast 22603]. He was certainly back at the Curia in Rome on April 22, 1288, two months after the election of Nicholas IV [Langlois, Registres de Nicolas IV, I, no. 582, p. 116]. He subscribed on September 3, 1288 at Reate [Langlois, Registres de Nicolas IV, I, no. 243, p. 40]. He died on August 10, 1309.

- Jean Cholet, Cardinal Priest of S. Cecilia (1281-1292). On August 27, 1283, Pope Martin IV sent Cardinal John of S. Cecilia extensive instructions on how to cause the throne of Aragon to be vacated, and how to conduct an election to replace the recalcitrant King Pedro [Baronius-Theiner 22, sub anno 1283 no. 25-34, pp. 515-518; Potthast 22061]. A document of May 5, 1284, names Cardinal Jean as Apostolic Legate in France, Navarre, Aragon, Valencia, Majorca, and the provinces of Lugdunum, Besancon, Vienne, Tarentaise, and Ebrudun [Potthast 22130; and cf. 22529 (November 10, 1286); Potthast 22550 (January 9, 1287); Potthast 22593 (ca. March 15, 1287); Potthast 22597 (undated); Langlois, Registres de Nicolas IV I p. 3-4 no. 6 (March 5, 1288); no. 315 p. 59 (September 20, 1288)] His legation ended in 1290, between September 20 and December 13, when he was already back in Orvieto. He died of fever on August 2, 1292, during the Sede Vacante, when a Conclave had not yet assembled [Baronius-Theiner 23, sub anno 1292, no. 20 p. 124]: unoque e patribus Gallo febribus deficiente.

Conclave

The circumstances under which the Conclave was held are mentioned by the newly elected Nicholas IV himself in his electoral manifesto, Judicia Dei abyssus [Raynaldus, sub anno 1288, v; p. 27; Langlois, Registres de Nicolas IV I p. 1-3 no. 1 (February 23, 1288)]:

Felicis siquidem recordationis Honorio Papa IV., praedecessore nostro, ut Domino placuit, ab hac luce subtracto, ejusque corpore cum exequiarum solmnitate debita tumuilo, nos tunc, ut praetangitur, episcopus Penestrinus cum fratribus nostris aliis in curia Romana praesentibus, in papatio S. Sabina de Urbe, in quo praedecessor ipse resederat, concordi voluntate convenimus, substitutioni Romani Pontificis soliciti vacaturi. Circa quod licet impedimenta varia, et praecipue diversarum et prolixarum infirmitatum angustia, quae quamplures de ipsorum fratrum collegio vexavere diutius, et —proh dolor !— nonnullos etiam subtraxerunt, aliquamdiu conatibus nostris obstiterint; demum tamen in I. Dominica praesentis quadragesima, nobis et reliquis fratribus tempore ipso praesentibus convenientibus in palatio supradicto, electa concorditer via scrutinii, et uno tantum facto publicatoque scrutinio, illo qui concordiam in sublimibus fuit facit, ut supponit devota credulitas assistente tanta finaliter in votis eorundem fratrum est inventa concordia, quod de ipsorum omnium unanimi voluntate ad conscendendam Petri cathedram secuta est de humilitate nostra concors electio et communis; fratribus ipsis instantibus importune, ut electioni consentiremus eidem.

The Conclave met in the papal palace at Santa Sabina, but there were various obstructions, especially the presence of diverse and long lasting medical problems, which afflicted several members of the College of Cardinals. Indeed, some of them died.

Deaths and Withdrawals

The Chronicon of Pietro Cantinelli (p. 57 Torraca) records the deaths of a number of cardinals in the year 1287:

Eodem anno infrascripti cardinales Rom(a)e de hac vita decesserunt: dominus Guittofredus de Alatro, dominus Ugo de Anglia, dominus Gervasius de Parixio, dominus Iordanus de Ursinis, dominus decanus parixiensis, dominus Ancerius de Francia...Eodem anno factus est papa dominus Ieronimus de Asculi cardinalis romanus, qui erat de ordine fratrum Minorum beati Francisci, et fuis [sic!] electus die XXII februarii, et vocatus fuit dominuis Nicholaus papa quartus ... Eodem anno dominus Comes cardinalis obiit in civitate romana.

They included Geoffrey of Alatri, Hugh of England, Gervaise of Paris, Giordano Orsini, Ancher Pantaleone, and the decanus Parisiensis Geoffrey de Bar, Cardinal Priest of Santa Susanna, whose titulus was given in commendam to Cardinal Benedetto Caetani on March 8, 1288 (Eubel I, p. 10 and p. 48 n.1). Ancher Pantaleon, Cardinal Priest of Santa Prassede, in fact, predeceased Pope Honorius, dying on November 1, 1286. Comes Casate, Cardinal Priest of Ss. Marcellino e Pietro was dead by April 8, 1287, as his funerary inscription in the Lateran Basilica indicates (Rohault, Le Latran, p. 175, Planche XXVIII; in translation only):

En l' an du Seigneur 1287 au 8e jour d'avril, le seigneur Jacques des Colonna, cardinal de Sainte-Marie in via lata, pour l' âme du seigneur Comte cardinal fit faire cette chapelle avec l'autel et tout le reste.

Natif de Milan, le Comte repose dans cette tombe, prêtre et cardinal. Qu'elle vienne à toi la splendeur d' en haut. Cher aux Lombards, issu de leur propre nation, illustre dans ta patrie, né d'un noble sang, tu portais avec sagesse et courage l'étendard de la Justice. Large envers les pauvres, lent pour tout ce qui est mauvais, grand dans le conseil, doux, dévoué comme l'agneau, ouvrant rarement la main aux présents, tu mourus juste; doué de tant de vertus pourquoi as-tu si vite été ravi par la mort? cette mort que pleurent Milan et la Curie romaine. Ah! pour que ces pleurs ne soient pas vaines, je le demande, que tous prient pour toi!

The original (metrical) Latin text gives a somewhat different impression from Rohault's translation (Galletti III, p. cccclxiii, no. 20):

| latere dextero: | ad altare Deiparae dicatum: | latere sinistro: |

|---|---|---|

| + ANNO DOMINI MCCLXXX VII MENSE APRIL' DIE VIII |

+ DE • MEDIOLANO • COMES • HOC • REQVIESCIT • IN • ANTRO PRESBITER • ET • CARDO • VENIAT • TIBI • SPLENDOR • AB • ALTO LOMBARDIS • CARVS • IPSORVM • GENERE • CREATVS DE • PATRIA • CLARVS • DE • MAGNO • SANGVINE • NATVS TV • SAPIENS • PECTVS • IVRIS • VEXILLA • FEREBAS SIMPLEX • ET • RECTVS • FAVSTV (sic) • POMPAQ • CAREBAS PAVPERIBVS • LARGVS • AD • PRAVA • PER • OMNIA • TARDVS CONSILIO • MAGNVS • MITES • DEVOTVS • ET • AGNVS MVNERIS • ACCEPTOR • RARVS • TV • IVSTVS • OBIISTI NEMINIS • ILLECTOR • CVR • SIC • CITO • MORTE • RVISTI HINC • MEDIOLANVM • ROMANA • Q • CVRIA • PLORET NE • FLEAT • IN • VANVM • PRO • TE • ROGO • QVILIBET • ORET |

+ DOMINVS IACOBVS • DE COLVMPNA CARD • SCE • M • IN • VIALATA PRO • ANIMA DNI • COMITIS CARD' • FECIT FIERI • HANC CAPELLAM CVM • ALTARI ET • OMNIBVS |

Many have taken April 8 to be the day of his death. But the inscription, in which the date formula is on the side of the altar and separate from the Elogium, would appear to be parallel with the other side of the altar, which is a dedicatory statement. The date formula, then, seems to indicate that April 8 is the date of the dedication of a memorial chapel, probably also that of the funeral. Comes de Casate died before that date, perhaps only a day or two before. April 8 is a terminus ante quem. The Annales Veronenses (p. 433), however, written by the brother of Matthew de Romano, do state that Comes de Casate died in April: item eodem anno [M.CC.LXXXVIII] de mense aprilis mortuus est dominus Comes de Mediolano Cardinalis.

Ptolemy (Tolomeo) of Lucca (Historia Ecclesiastica Book 24, chapter 9) records that the Cardinals were enclosed in the Pope's palace at Santa Sabina for a long time without being able to agree on a pope. During this time, in the summer, a plague broke out ('plague' being a general term for any sort of contagious disease, peste, without having to be the bubonic plague), during which six of the cardinals died, and caused the rest to return to their own houses. One can say that the English Cardinal, Hugh of Evesham died, on July 28, 1287 [Register of Bishop Godfrey Gifford II, p. 333; Annales Monastici IV ed. Luard, pp. 493-494]. The only cardinal to remain in Conclave was Cardinal Girolamo Masci d' Ascoli, OFM, the Bishop of Palestrina, quia in profunda aestate semper habuit prunas copiosas in aula sua, et in camera, et in aliis officinis. (see: Muratori, Annali d' Italia 19, 96.) The text of Ptolemy is quoted by Piatti (p. 323, with errors):

Li Cardinali si rinchiusero nel palazzo di Santa Sabina; ma perchè questo luogo era di poca salute nell'Estate, molti di essi s'infermarono, e ne morirono sei o sette, tra quali Giordano Orsini, il Conte di Milano, Ugone d' Inghilterra, Gervasio d' Angers, Decano di Pisa, ed il Signore Antonio. Il perchè tutti partirono alle proprie abitazioni tornando.

Piatti invents a "Signore Antonio" in his Italian translation because he does not know of Cardinal Ancher (Pantaleone). In Tolomeo's Latin (which still does not know the name Ancherus) the text reads:

multi Cardinales infirmati sunt ibidem, et mortui circa sex, vel septem, inter quos fuit Dominus Jordanus de Ursinis, Dominus Comes de Mediolano, Dominus Ugo Anglicus, Dominus Gervasius Andegavensis, et Decanus Pisanus, et Dominus Anteis.

Tolomeo is certainly exaggerating when he attributes the break-up of the Conclave to the deaths of six or seven Cardinals. Two in his list were certainly dead before the Conclave began, let alone "l' Estate", and by adding a seventh he is going beyond the facts. Nor did they die within a short time of each other. Giovanni Villani's Chronica (Book VII, cap. cxviii; coll. 317-318), makes a basic statement about the election. Pope Nicholas IV was elected on the Feast of St. Peter's Chair, February 22:

Nelli anni di Christo 1287 [1288 did not begin until March 25], il dì della Cattedra Santi Petri, fu eletto Papa Niccola Quarto d'Ascoli della Marca. Questi havea nome Girolamo, & fu Frate Minore, & per sua bontà e scienza fu fatto Ministro generale de l'Ordine, anzi che fosse ad altra dignità; poi fu Cardinale, poi Papa & sedette quattro anni, & un mese, & VIII dì; e dopo la sua morte vaco la Chiesa II anni, & III mesi.

Platina (Historia , p. 228) discusses the Conclave briefly at the end of the life of Honorius IV, getting Cardinal Ancherus' name almost correctly, and noting that the Conclave was held at the Pope's residence near Santa Sabina:

Adeo vero aulicos amavit [Honorius], ut quotannis, aestate praesertim, Tibur proficisceretur vitandi aestus urbani caussa, unde multae aegritudines oriuntur. Mortuo autem Honorio, decem mensibus sedes tum vacat. Nam cum apud sanctam Sabinam conclave haberetur, multi Cardinales repentina aegritudine fiunt correpti, quorum de numero moritur Iordanes Ursinus Comes Mediolanensis, Hugo Anglicus, Gervasius Andegavensis, Decanus Parisiensis et Antherus vir insignis. Hanc ob rem soluto conclavi, in aliud tempus magis salubre rem ipsam rejiciunt, maxime vero cum terraemotus ipsi, qui tum permagni fuere, religionem quandam iniecerint quo minus tum quidam id fieret.

How remarkable that Gregory X's regulations for the Conclave, only fifteen years old, were being abrogated again.

One event is known from the time before the Cardinals dispersed in fear of the plague. Raynaldus reports (sub anno 1287, x; from a ms. source) that the people of Perugia, who had made an attack on a castle in the Diocese of Nuceria, in disobedience of the instructions of the Praeses of the duchy of Spoleto and in violation of the rights of the Roman Church, were ordered by the Sacred College of Cardinals to desist from their operations:

Vacante Sede, Perusini arcem prope Gualdum Nucerinae diocesis, contemptis censuris quas ducatus Spoletani praeses incusserat, excitarunt; quo facto, cum non parum Romanae ecclesiae jura invaderent, Sacer Cardinalium Senatus coeptis eos desistere jussit.

Election of Cardinal Girolamo

When the Cardinals reassembled in February, 1288, there were seven electors left: Latino Malabranca, Bentivenga de Bentivengis, Girolamo Masci, Bernard de Languissel, Matteo Rosso Orsini, Giacomo Colonna, and Benedetto Caetani. Girolamo Masci d' Ascoli, OFM., Suburbicarian Bishop of Palestrina, was elected on February 22, 1288. It was the Feast of the Chair of St. Peter. He took the name Nicholas IV in memory of Nicholas III. He was the first Franciscan friar to become Pope.

Cardinal Girolamo had refused election to the Papal Throne before he was finally prevailed upon to accept. This story, according to Piatti (p. 324) can be found in the Annali of a 14th century Augustinian canon named Enrico (Heinrich) of Rebdorf (Chevalier, Repertoire des sources historiques du Moyen Age I, 2097). Enrico wrote (Freher I, 605):

Nicolaus IV. de ordine fratrum Minorum, Doctor Theologiae, anno Domini MCCLXXXVI electus sedit annis V. & bis electus cum lacrymis resignavit, tertio compulsus ab omnibus Cardinalibus acquievit.

This is not quite in accord with Pope Nicholas' own first encyclical, written on February 23 from the Lateran, announcing his election. Nicholas pleaded his unworthiness at great length, as well as the aweful difficulty of the position of Supreme Pontiff, and "eorumdem fratrum importunitate diversarum excusationum obicem opponendo qua potuimus reluctatione restitimus, aperte negantes electioni praemissae praestare consensum, et tam ipsi quam iuri nobis ea quaesito renuntiantes expresse (Raynaldus, sub anno 1288, vii; p. 28).

Nonetheless the Cardinals persisted:

Verum fratres iidem nostrae resistentiae instantius obviantes, electione nihilominus repetita concordi, ut ei sonsentiremus, et institere ferventius, et in virtute obedientiae injuxerunt.

(in Piatti's translation, 324-325):

Alla importunita dei Fratelli che non esaudirono le nostre scuse, abbiamo fatto resistenza con quanto vigore potemmo, costantemente negando di prestare il nostro assenso alla fatta elezione, e tanto ad essi quanto al diritto prestatoci colla elezione abbiamo solennemente rinunziato. Ma eglino con maggior vigore alla nostra resistenza opponendosi con replicata elezione noi promossero e ci costrinsero di prestare l'assenso, ed in virtu di santa obbedienza cel comandarona ....

This appears to state that there were two votes, not three, as Heinrich of Rebdorf would have it. The first was on February 15, the second Sunday in Lent. That vote received a solemn renunciation. It took an additional week to convince Cardinal Girolamo of the wisdom of his election (Raynaldus, viii), which was then taken to an additional scrutiny:

ne sub obedientia nutriti diutius eam contemnere pertinaciter et mundi graviter guerrarum multiplicatione divulsi, Terraeque Sanctae quasi omni auxilio destitutae pericula differendo provisionem Ecclesiae negligere censeremur; tandem acquievimus eorundem fratrum instantiae, ipsorum urgente praecepto; collaque debilia jugo submisimus apostolicae servitutis, praestantes electioni, ut praemittitur, iteratae consensum, anxiato et humiliato spiritu supplicando, ut ille qui nos jugem idem subire concessit, sic ad ipsum portandum debilitatem nostram robore fulciat, etc.

This second election, the one of February 22, he finally agreed to. This is one of the rare times when the usual rhetoric about being unwilling was true.

Coronation

Nicholas IV, aged 65, was crowned on February 24, 1288 (a.d. vi Kal. Mar.), two days (biduo post) after his election, at St. Peter's, by Goffredo da Alatri, Cardinal Deacon of S. Giorgio in Velabro, the Cardinal Protodeacon (Panvinio, 185; Antonius Felix Mattheus, p. 54 n. 1; Novaes, 14-15). On the same day, VII. Kalend. Martii, Nicholas wrote from the Lateran to the King of England, Edward I, Iudicia Dei abyssus (Schedario Baumgarten II, 4205, from the Public Records Office, London; full text in Raynaldus sub anno 1288, iii ff.).

Eubel (Hierarchia Catholica I, 11), however, accepts an alternate tradition that he was elected on February 15 and crowned on February 22. It appears, to take just one example in the continuation of Matthew Paris' chronicle by Matthew of Westminster called the Flores Historiarum (Luard p. 68):

Anno gratiae MCCLXXXVIIIo, Quintodecimo die mensis Februarii frater Jeronimus de ordine fratrum Minorum, sed presbiter cardinalis, in summum pontificem consecratur, et Nicholas Papa quartus vocatur. Hic peritus in Graeca lingua partier fuerat et Latina. Graecorum ductor et interpres extitit in ultimum consilium Lugdunense.

This opinion is fully treated by Antonius Felix Mattheus in his edition of Hieronymus Rubeus' Life of Nicholas IV (pp. 15-20). It derives from Nicholas' own inaugural encyclical letter, where he states that he was elected unanimously by scrutiny of the Cardinals on the Second Sunday of Quadragesima (February 15). But that was the first election, which he refused. The second election, which he accepted, took place on February 22. Gregorovius (p. 508, citing no sources) is made to say in English translation that "He was elected on the return of the cardinals to the Aventine in the winter, but was not consecrated until February 22, 1288." This is a mistranslation of the German (p. 485): "Als die Cardinäle im Winter auf den Aventin zurückgekehrt waren, wählten sie ihn, doch erst am 22.Februar 1288 zum Papst." Gregorius, in fact, endorses the date of February 22 for the election of Nicholas IV. See also J. D. Mansi's note in Raynaldi (p. 26).

On May 29, 1289, Pentecost Sunday, Nicholas was at Reate, where he crowned Charles II as King of Sicily [F. Ehrler, Archiv für Literatur- und Kirchengeschichte 5 (1889), 569].

One of Nicholas IV's most important acts, as far as the College of Cardinals was concerned, was the bull Caelestis Altitudo (July 18, 1289), in which he agreed to split papal income into two parts, assigning the other part to the College of Cardinals, to be shared equally. This finally put the Camera Cardinalium on a regular financial footing.

Bibliography

Ernest Langlois (editor), Les registres de Nicolas IV Tome Premier (Paris: Albert Fontemoing 1905) [BEFAR, 2 série, v].

Francesco Torraca (editor), Petri Cantinelli Chronicon (Città di Castello 1902) [Rerum Italicarum Scriptores, XXVIII pars II]. The Brother of Mateo de Romano: Monumenti storici publicati dalla R. Deputazione Veneta di storia patria. Serie terza. Cronache e diarii, Vol. II. Antiche Cronache Veronesi (Venezia 1890), pp. 409-469 "Annales Veronenses" Giovanni Villani, Ioannis Villani Florentini Historia Universalis (ed. Giovanni Battista Recanati (Milan 1728) [Rerum Italicarum Scriptores, Tomus Decimustertius]. Enrico (Hainricus Rebdorfius): Marquardi Freheri Rerum Germanicarum Scriptores editio tertia (curante Burcardo Gotthelffio Struvio) Tomus Primus (Argentorati: sumptibus Ioannis Reinholdi Dulsseckerii 1717), pp. 598-644.

Odoricus Raynaldus [Rainaldi], Annales Ecclesiastici ab anno MCXCVIII. ubi desint Cardinalis Baronius, auctore Odorico Raynaldi. Accedunt in hac Editione notae chronologicae, criticae, historicae... auctore Joanne Dominico Mansi Lucensi Tomus Quartus [Volume XXIII] (Lucca: Leonardo Venturini 1749), sub anno 1287 no. ix (p. 21); sub anno 1288 no. i (p. 26).

Actenstücke: A. Fanta, F. Kaltenbrunner, E.v. Ottenthal (editors), Actenstücke zur Geschichte des Deutschen Reiches unter den Königen Rudolf I. und Albrecht I. (Wien 1889).

Bartolomeo Platina, Historia B. Platinae de vitis pontificum Romanorum ...cui etiam nunc accessit supplementum... per Onuphrium [Panvinium]... et deinde per Antonium Cicarellam (Cologne: Cholini 1626). Bartolomeo Platina, Storia delle vite de' pontefice edizione novissima Tomo Terzo (Venezia: Ferrarin 1763) 148-153. Antonius Felix Matthaeus, Nicolai IV. Pont. Max. Vita, ex codicibus Vaticanis cum observationibus et dissertationibus [per Hieronymum Rubeum composita] (Pisis: Augustinus Pizzoro, 1766). Lorenzo Cardella, Memorie storiche de' cardinali della Santa Romana Chiesa Tomo primo Parte secondo (Roma: Pagliarini 1792). Abbé Roy, Nouvelle histoire des cardinaux françois Tome quatrième (Paris: Poincot 1787). Giuseppe Piatti, Storia critico-cronologica de' Romani Pontefici E de' Generali e Provinciali Concilj Tomo settimo (Poli 1767). Ludovico Antonio Muratori, Annali d' Italia Volume 19 (Firenze 1827), 75-78. Giuseppe de Novaes, Elementi per la storia de' Sommi Pontefici terza edizione Volume IV (Roma 1821) 11-15. G. Moroni, Dizionario di erudizione storico-ecclesiastica Volume 48 (Venezia 1848) 10-11. Antonino Franchi, Nicolaus papa IV (Ascoli: Cassa di risparmio di Ascoli Piceno, 1990), pp. 90-94. Diego Quaglioni, Storia della Chiesa: La crisi del trecento e il papato avignonese : 1274-1378 (Cinisello Balsamo : San Paolo, 1994).

Bernhard Pawlicki, Papst Honorius IV. Eine Monographie (Münster 1896). Otto Schiff, Studien zur Geschichte Papst Nikolaus' IV. (Berlin 1897). Augustin Demski, Papst Nikolaus III, Eine Monographie (Münster 1903). F. Gregorovius, History of Rome in the Middle Ages, Volume V.2 second edition, revised (London: George Bell, 1906) 507-510.

Henry Richards Luard (editor), Annales Monastici. Vol. IV. Annales Monasterii de Oseneia (A. D. 1016–1347)... (London Longmans, 1869). Henry Richards Luard (editor), Flores Historiarum Vol. III. A.D. 1265 to A. D. 1326 (London: HM Stationery Office/Eyre & Spottswoodie 1890).

G. Rohault de Fleury, Le Latran au Moyen Age (Paris: Morel 1877). Pietro Luigi Galletti, Inscriptiones Romanae Infimae Aevi Romae Exstantes Tomus Tertius (Romae: Typis Generosi Salomonj Bibliopolae, MDCCLX).

J. B. Sägmüller, Thätigkeit und Stellung der Kardinale bis Papst Bonifaz VIII. (Freiburg i.Br.: Herder 1896). Karl Wenck, review of Sägmüller, Thätigkeit, in Göttingsche gelehrte Anzeiger 163 (1900) 139-175.

G. Marchetti Longhi, "Il cardinale Gottifredo di Alatri, la sua famiglia, il suo stemma ed il suo palazzo," Archivio della Società romana di storia patria 85 (1952), pp. 17-49. G. Zander, "Il palazzo del cardinale Gottifredo da Alatri," Palladium 1 (1951); 2 (1952), pp. 109-112.