Inversion Layers

In a typical situation, the

atmosphere (with regard to the troposphere) becomes cooler as elevation

increases. An “inversion” occurs when a section

of the atmosphere becomes warmer as the elevation increases. Inversion layers are a significant factor in

the formation of smog in

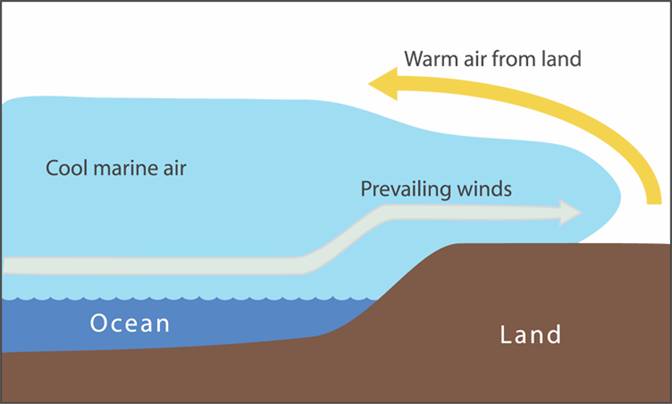

The first diagram (Fig. 1)

shows what is known as a Marine Inversion.

This occurs when cool, moist air that originates over the ocean is blown

onto land by our prevailing westerly winds.

The cool temperature of this air makes it more dense, so it readily

flows underneath the warmer, drier air that is present over the basin. This type of air flow is also accentuated by

the fact that land surfaces are heated more rapidly during the day than the

ocean. This extra heating creates rising warm air, which then draws in the

cooler ocean air.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

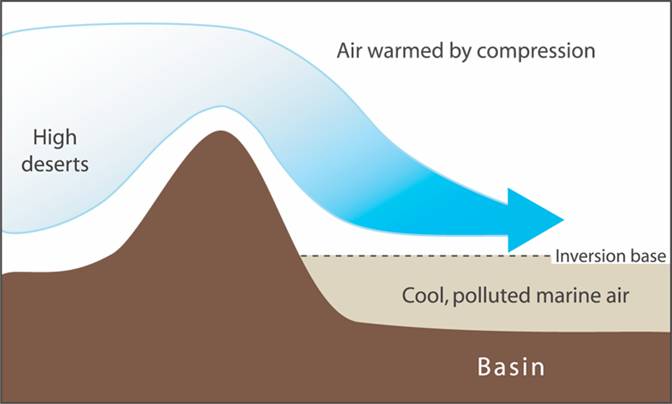

The second diagram (Fig. 2)

shows a Regional Subsidence Inversion. This occurs when air flows down from a

higher location to a lower elevation. As

air sinks, or descends, it’s warmed because of the compression it undergoes. Typically, this air is also dry. Not only has it originated over a dry land

mass, but any moisture it may have contained at one time was likely condensed

and precipitated out as it rose over our local mountains prior to its descent

into the basin. Mixing of the air masses

can occur on occasion, but once the warm, dry air (appearing in

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

The third diagram (Fig. 3) shows a High Pressure

Inversion. Because high pressure systems

are a function of descending air, we again see a situation of warm, dry air

sinking to act as a cap over our cooler marine air. This is a regular occurrence for

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Written by Anna Huber.

Illustrations from Earth Under Siege, © R. Turco, 2001

Last updated,