Conflict is inevitable and pervasive in all kinds of human interactions. How it is managed (and mismanaged) has strong effects on the individuals and organizations involved. This module summarizes some basic concepts, models, and suggestions about managing conflict effectively, grounded in and consistent with the literature.

One colloquial definition of conflict is that it occurs when two people try to occupy the same "space" at the same time. This space could range from a physical space, such as the last open seat on a crowded bus, to psychological space, in which each party believes that there are incompatibilities in what the various parties want. One useful definition of conflict (Wilmot & Hocker (2010), Interpersonal Conflict, p.11) is: Conflict is an expressed struggle between at least two interdependent parties who perceive incompatible goals, scarce resources, and interference from others in achieving their goals.

How we deal with conflict is contingent on many factors, including the individuals involved, their roles and relationships, the issues, and the context.

For a long time, many people, even professionals, considered conflict as "bad" ...something to be avoided and, if present, to be "resolved." There now is wide-spread acceptance (starting early with Mary Parker Follet in c. 1941) that conflict has functionality - that it can have both positive and negative effects. This view led to the present state of calling the field "conflict management," rather than conflict resolution.

It is easy to identify potential negative consequences of conflict. However, it is instructive to brainstorm potential positive effects of conflict, e.g.: conflict can cause problems to surface and be dealt with, clarify varying points of view, stimulate and energize individuals, motivate the search for creative alternatives, provide vivid feedback, create increased understanding of one's conflict styles, test and extend the capacities of group members, and provide a mechanism for adjusting relationships in terms of current realities. Properly managed, conflict can help to maintain an organization of vigorous, resilient, and creative people. The goal of conflict management, then, is to increase the positive results, while reducing the negative ones.

CONFLICT EPISODE MODEL

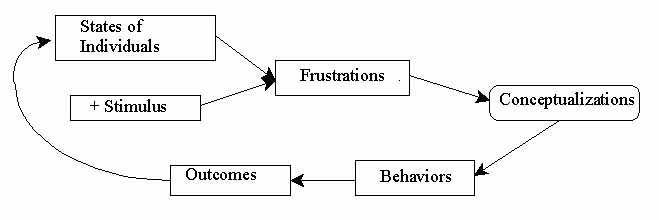

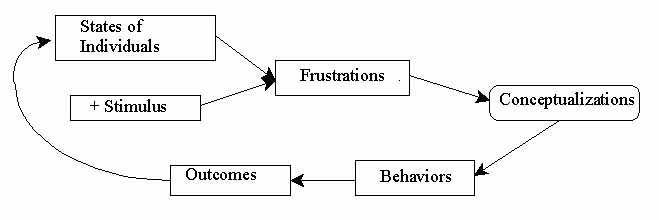

What goes on in a conflict? It is important to be aware of important variables that may influence conflict behaviors as a basis for intervening productively in conflict situations. The following model is a slight modification of the process model of Thomas (1976, 1979). It's a useful way of viewing conflicts.

Conflicts are considered to occur in cycles or episodes, each of which may be quite short, e.g., a few seconds or minutes. Each episode is influenced by the outcomes of previous episodes and also influences future episodes. The model of a conflict episode has six components or stages. For simplicity, the description below deals with only two individuals in conflict, although the model extension to multiple individuals is direct.

The first stage represents each individual's entering state, which is determined by such variables as his or her behavioral predispositions (personality, if you please), events and pressures from the social environment, recent experiences with significant others, and previous experiences, especially conflict episodes, with the other party. Typically, some stimulus (the second component) occurs that initiates or catalyzes an episode, although it need not be an explicit event.

The entering state and stimulus lead to frustration (the third stage of the model). Frustration may result from a wide variety of stimuli--for example, active interference with one group member's actions by another, competition for recognition, the breaking of an agreement, or the giving of an overt or imagined insult (e.g., you do not agree with my ideas, you prevent me from getting the information, money, time I need..., you undermine my influence with someone else). In both this and the following stage, the inferences and attributions of each individual are primary determinants of behavior, and the resulting perceptions of the conflict situation often vary widely across individuals.

The fourth step, conceptualization, is vitally important. The conceptualization of the situation by each group member forms the basis for his or her reactions to the frustration and subsequent behavior. This step in the episode could be thought of as each party answering and reacting to the imagined answers to such questions as: What's going on here? Is it good or bad for me? Why is this other person doing this to me? An example of a conceptualization is: "You just can't trust that (type of) person." A dispute between a group member and the leader might be conceptualized by the leader as "this guy is acting out his counter-dependent position and trying to take over the group" and by the member as "I must push this issue for the sake of the group because nobody else has the guts to stand up to this arrogant show-off." Conceptualizations involve inferences, attributions, and evaluations that may be far removed from the actual words and actions of the individuals during the episode.

Each party in a conflict develops his or her own implicit conceptualization of the situation. This is done quickly and usually tacitly (i.e., the individual doing it is not conscious of the process).

There are many different ways to conceptualize and respond to the same situation - seldom will the parties conceptualize in the same way. Usually they are blind to and/or want to ignore any alternative conceptualizations, e.g., a conflict between teachers and administration in a school district was conceptualized by the school board as "this is anarchy, trying to take over the running of this district" ...and by teachers as "we must push this issue to retain quality in the education of our students." The ways each party conceptualizes the problems and episode have a great deal of influence over the chances for a constructive outcome, the behaviors that will result, and the kinds of feelings that will be created during the conflict episode.

The fifth step in the conflict model is behavior (i.e., a sequence of behaviors and interactions between the two parties). The initial behavior of each individual is determined heavily by his/her conceptualization. The behaviors of each party have an effect on the subsequent behavior of the other. This interaction tends to increase or decrease the level of conflict.

The sixth and final step in the conflict episode model is the outcome or result of the conflict episode. The outcome refers to the state of affairs that exists at the end of the episode, including decisions, actions taken, agreements made, and feelings of the participants.

Subsequent episodes may happen, with similar or different issues. The process described above is repeated for each episode, with the outcome of previous episodes affecting the entering state of each individual in subsequent episodes. Succeeding episodes can move higher in conflict intensity (escalation) or lower in intensity (de-escalation)

OPPORTUNITIES FOR INTERVENTION IN A CONFLICT

This model can help us identify various points for intervention in managing conflict - both as a participant and when assisting others with their conflicts - for example:

CONFLICT RESPONSE MODES

The behavior of the participants is one of the steps or events in the conflict model described in the preceding section. A key determinant of behavior is the primary orientation(s) (mode(s) of dealing with conflicts) of each individual. There are many different ways to respond. Most of us tend to use a limited range of responses, but could profit from enlarging our repertoire.

There have been many models of conflict response modes in the literature since c. 1964, each categorizing similarly an individual's orientation in terms of two dimensions, roughly emphasis on satisfying his/her own concerns and emphasis on satisfying concerns of the other(s). Such models are useful and can be used to describe typical ways that individuals behave in response to conflict, thus providing a helpful tool in conflict management. For convenience, most of these models define five primary conflict response modes, representing the four extremes or polarized modes plus a center mode of compromising. The diagram below displays some of the labels that have been applied to both the two dimensions and the five primary response modes.

The competing orientation or response mode involves an emphasis on winning one's own concerns at the expense of others' concerns -- to be highly assertive (often aggressive) and uncooperative. This is a power-oriented mode, with efforts to force and dominate the other, often in a "win-lose" fashion, although it may be seen by the actor as "merely asserting my rights."

Accommodating is both unassertive and cooperative, concentrating on trying to satisfy the other's concerns with little attention to (or even at the expense of) one's own concerns. It includes appeasement, yielding to the other, and acquiescing. Sometimes there is a note of generosity or self-sacrifice in this mode.Collaborating is a mode with great emphasis on satisfying the concerns of all parties--to work with the other party cooperatively to find an alternative that integrates and fully satisfies the concerns of all. This mode is both assertive and cooperative. It also requires a relatively large initial investment in time and energy to do such joint problem solving.

Avoiding reflects inattention to the concerns of either party--a neglect, withdrawal, indifference, denial, or apathy. It is neither assertive nor cooperative.

The remaining orientation, compromising (sharing or bargaining) is intermediate in both assertiveness and cooperativeness. It reflects a pragmatism or preference for settling on an expedient, mutually acceptable solution that partially satisfies the concerns of both parties. It might mean trading concessions, splitting the difference, or finding a satisfactory middle ground.

Each of us tends to be better at and more comfortable with certain types of behavior in conflict situations. This does not mean that we always respond in the same way. In terms of the five modes just described, however, most individuals tend to make predominant use of one or a few of the modes, while making relatively less use of the remainder. Each of the modes has value; none is always good, bad, or preferable in all situations. One worthwhile goal for individuals is to increase their repertoire of responses to conflict plus the flexibility to use various modes in different situations and in appropriate ways.

Some of the potential advantages of these five primary response modes plus situations in which each would be appropriate are outlined below. These lists came from small group brainstorming exercises in my Mgt. 456 classes several years ago, with some editing and inputs from me. The students clearly made use of material in the two textbooks in use (Wilmot & Hocker, 2010; and Lewicki, et al., 2007), in addition to their experience. Many other literature sources have also discussed this topic, e.g., Blake & Mouton (1964, 1978), Filey (1975), Pruitt & Rubin (1986), Rahim (1990). Thomas (1976, 1977, 1979, 1992), Thomas & Kilmann (1974).

Competing

Accommodating

Collaborating

Avoiding

Compromising

The entire range of conflict responses, represented by the five primary modes above, is useful and of value. Our challenge is in broadening our repertoire and increasing our flexibility in being able to respond in a wide range of modes. The art is in learning how and when to make appropriate use of the full range of responses. Further, it is appropriate and useful to use various modes at different stages in a single conflict management process -- one does not have to or should stay with a single mode throughout dealing with a conflict situation.

The importance of good skills in managing conflict, our own and when helping others, can not be overemphasized. Our present skills can be enhanced and improved, with attention and effort. We will talk later about various ways of intervening and helping to manage conflicts.

| Last modified June 26, 2010 | Copyright 1976-2010 Rex Mitchell |