SEDE VACANTE 1730

February 21, 1730—July 12, 1730

Annibale Cardinal Albani

ANNIBALE CARDINAL ALBANI (1682-1751), was born at Urbino on August 15, 1682. His uncle became Pope Clement XI in 1700 (dying on March 19, 1721). Annibale was created Cardinal Deacon on December 23, 1711, being appointed to the Deaconry of S. Eustachio on March 2, 1712. He became Archpriest of St. Peter's Basilica in 1712, where he had long been a Canon, and was promoted to be Cardinal Priest of S. Clemente in March, 1722, for which he was finally ordained a priest in October. He was appointed Camerlengo of the Holy Roman Church on March 29, 1719, a post he held until 1747. He became bishop of Sabina on July 24, 1730, and was translated to Porto and Sta. Rufina in 1743. From 1719 he was director of the English hospital of St. John in Jerusalem.

|

AG grosso SEDE • VACAN | TE • MDCCXXX Shield with the Coat of Arms of Annibale Card. Albani, Camerlengo of the Holy Roman Church (1719-1747), upon the Cross of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem, crossed keys above, surmounted by Cardinal's hat with six tassels on each side; the Ombrellone over all. |

|

Berman, p. 174 #2602. |

The Dean of the Sacred College of Cardinals was Cardinal Francesco Barberini, Bishop of Ostia and Velletri.

Msgr. Giovanni Battista Gamberucci, Archbishop of Amasia (born in Rome on July 4, 1674), Bishop Assistant at the Papal Throne, was the Papal Master of Ceremonies and Secretary of the Congregation Ceremoniale.

Msgr. Domenico Rivera of Urbino, Protonotarius apostolicus de numero participantium supernumerarius, Basilicae Principis Apostolorum de Urbe canonicus, was the Secretary of the Sacred College of Cardinals.

Death of Pope Benedict XIII

During Mass on Christmas Day, 1729, Pope Benedict, who had begun the ceremonies, fainted (era caduto in uno sventimento) and was unable to continue, and Cardinal Annibale Albani, the Camerlengo, had to finish in his place by consuming the Host and the Wine [La Storia degli anni 1730., e 1731. , pp. 82-83]. The Pope appeared to recover, however, and resumed his regular activities in January and February. On the 8th of February, on the nomination of the Stuart "King of England", the Pope created Msgr. Alamanno Salviati of Florence, Protonotary Apostolic and President of Urbino, a cardinal.

In February of 1730, Rome was in the grip of an epidemic [La Storia degli anni 1730., e 1731. , p. 84-85]. Monsignor Girolamo Lioni wrote to his brothers on February 18 [Storia di un conclave, p. 11 n.1]:

Anche qui è arrivata la fatale influenza dell' Europa. In questa settimana è caduta e va cadendo ammalata tutta Roma. I frati, le monache, le genti più custodite, tutti sono a letto. È raffreddore, che dura tre giorni, e poi ognuno risana. Non si apprende gran cosa. Io sto bene, e cercherò di starvi. Anche l'Eminentissimo Padrone s' è totalmente riavuto. Martedì morì l' Eminentissimo Ansidoli [February 14]. Il suo Vescovato di Perugia l'ha avato il Padre Mons. Andujar, domenicano milanese-spagnuolo, bibliotecario segreto di Nostro Signore, uomo degnissimo per dottrina e probità. È un gran pezzo che non s'è fatta promozione tale. Va morendo l' Eminentissimo Pipia [died February 21]....

On the night of 18/19 February, the Pope began to show the symptoms of catarrh and fever that went with the epidemic, but immediate treatment with drugs and broth seemed to release him from the grip of the phlegm [La Storia degli anni 1730., e 1731., p. 85]. He was strong enough to say Mass on the 19th. On the 20th, after he recited Matins and took his morning chocolate, he wanted to get out of bed, but his doctors dissuaded him. On the 21st he was much worse. He wanted to call a consistory of Cardinals, but there turned out to be no time for them to assemble. Four Roman hours after noon, the Pope died. The Camerlengo, Cardinal Albani, was not present. He himself was ill and staying at Soriano. His functions at the deathbed and immediately thereafter were carried out by Cardinal Corsini. [La Storia degli anni 1730., e 1731., p. 86]. Cardinal Pipia died some five hours after the Pope [Lioni, 14]. Msgr. Andujar did not get the rumored appointment to Perugia. Some weeks later the new Pope gave it to Msgr. Francesco Ferniani.

Pope Benedict XIII (Vincenzo Orsini, OP) died on February 21, 1730, the last day of Carnival, the nineteenth day after his eighty-first birthday. His biographer in Platina states [Platina IV (Venezia: Domenico Ferrarin 1765), 516]:

Fu questo [Consistory of February 6, 1730] l' ultimo, ed il ventesimo nono de' Cardinali che Benedetto XIIII. promosse; imperciocchè pochissimi giorni dopo quasi senza avvedersene terminò di vivere. Attaccato egli da un fiero catarro con febbre la notte de' 18 de Febbrajo, dopo che pareva che avesse alquanto respirato, sentendosi tuttavia mancare, intimò il giorno 21. un Concistoro a tutti i Cardinali, che erano in Città, e nella Campagna. Non giunsero però a tempo gl' invitati Cardinali, poichè quattro ore dopo il mezzo dì, rendette l' anima a Dio....

This scenario is confirmed by Msgr. Lioni in a letter of February 25, adding that the Pope intended to name yet another cardinal, Archbishop Nicolò Saverio Santa Maria, Bishop of Cyrene, the Pope's Maestro di Camera [Storia di un conclave, p. 14]:

Quando Nostro Signore fu assalito dalla soffocazione pei catarro, e s' accorse di morire, chiamò per intimare il Concistoro. Monsignor Maggiordomo cercò di far tirar avanti, ma il Papa ritornò a comandarlo con fretta. Furono però spedite per più sollecitudine le corazze a cavallo per chiamare i censori, ai quali spetta il far l' intimazione del Concistoro ai cardinali. Intanto che si spedivano le corazze suddette il Papa morì. Per altro monsignor Santa Maria era cardinale.

Msgr. Santa Maria never became a cardinal, but instead became a major target of subsequent investigations, and his appointment as Consultor at the Holy Inquisition was cancelled [La Storia degli anni 1730., e 1731., p. 110].

The body of the late pope was enbalmed, and transferred to the Vatican Basilica, where it was laid in the Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament. His Funeral Oration was preached by Fr. Tommaso Agostino Riccini, OP, a member of the Arcadian Academy. The throne of Peter was vacant for eight months and twenty-one days. Benedict's administration was hated by nearly everyone in Rome both because of his maladministration and because of his giving a free hand to Niccolò Cardinal Coscia, his evil genius [Lioni, 11-14]. Coscia, in fear of his life, fled immediately upon the death of the Pope to Cisterna (the seat of the Duke of Sermoneta). The Duke wrote to Cardinal Barberini about his situation, and, under a safe conduct from the Sacred College, Coscia returned quietly to Rome and took part in the Conclave [Lioni, 15-16; on Coscia's fate, Montor, 12-13; Cartwright, 136-137].

Then the Father General of the Jesuits, Michelangelo Tamburini, SJ, died on Wednesday, March 1, at the age of 83. The King of Portugal, John V (1706-1750), was so annoyed at the Court of Rome that he forbade the Jesuits in Portugal to send a delegate to the General Congregation to elect Tamburini's successor [La Storia degli anni 1730., e 1731., p. 94].

The Cardinals

A list of the Cardinals is given by Mario Guarnacci, Vitae et Res Gestae Pontificum et S.R.E. Cardinalium II (Roma 1751), at columns 596-600. Another list, of those cardinals present in the Conclave, is provided by Relazione distinta della solenne Coronazione (1730), 7-8.

The official list of all Conclavists and their Cardinals is attached to Clement XII's motu proprio granting the usual privileges and absolutions to the Conclavists (Bullarium Romanum 23 [Augustae Taurinorum 1872], 28-31 (July 14, 1730). Cf. Clemens XII, Gratiae et privilegia conclavistis postremi conclavis concessa (Roma: Camera Apostolica 1730).

- Francesco Barberini, iuniore (aged 67), a member of the family of the Princes of Palestrina. Bishop of Ostia e Velletri. Great-grandnephew of Urban VIII. Died August 17, 1738.

- Francesco Pignatelli, Theat. (aged 78), Bishop of Porto e Santa Rufina (1725-1734) . Nuncio to Poland (1700-1703) Archbishop of Naples (1703-1734).

- Giacomo Boncompagni (aged 77), Bishop of Albano (1724–1731). Archbishop of Bologna (1690-1731).

- Pietro Ottoboni (aged 62) [Venetus], Bishop of Sabina (1725–1730), and Cardinal Priest of S. Lorenzo in Damaso in commendam (1725–1740). S.R.E. Vice-Cancellarius. Grandnephew of Alexander VIII.

- Lorenzo Corsini (aged 78) [Romanus], Bishop of Frascati (1725-1730), previously Cardinal Priest of S. Pietro in Vincoli (1720–1725). Doctor in utroque iure (Pisa). Cleric of the Apostolic Camera. Prefect of Grace in the Apostolic Camera. Titular Archbishop of Nicomedia in Turkey (160), so that he could be Nuncio in Vienna; he was rejected, however, by the Emperor. Treasurer General of the Apostolic Camera (1695). Prefect of the Signature of Grace. Died 1740, as Bishop of Rome.

- Tommaso Ruffo (aged 66) [born in Naples], son of the Duca di Bagnara. Bishop of Palestrina (1726–1738), previously Cardinal Priest of S. Maria in Trastevere (1709–1726). Bishop of Ferrara (1717-1735).

- Benedetto Pamphilj (aged 76) [Romanus], Cardinal Priest of S. Maria in Via Lata (1693–1730) [created September 1681. Died during the Conclave on March 22, 1730; buried in S. Agnese in Piazza Navona] Bibliothecarius S. R. E. and Archivist S. R. E. Archpriest of the Lateran Basilica (1699-1730). Grandnephew of Innocent X.

- Giuseppe Renato Imperiali (aged 78) [Genoa], of the family of the Counts of Francavilla in the Kingdom of Naples; grand-nephew of Cardinal Lorenzo Imperiali. Cardinal Priest of S. Lorenzo in Lucina (1727–1737). Comissary General of the Sea in the Apostolic Camera (1687). Superintendant of the Mint. Treasurer of the Apostolic Camera S. R. E. Castellan of the Castel S. Angelo (September-December, 1689). Created Cardinal on February 13, 1690. Cardinal Deacon of S. Giorgio in Velabro. Legate in Ferrara. In 1711 he was Legate to the King of Spain, Charles III. Protector of Ireland. Protector of the OESA. Protector ot the Church of S. Bartolommeo de' Vaccinari [V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma XII, p. 262, no. 420]. Abbot Commendatory of the Abbey of S. Niccolo de Casulis (Casola, Otranto), as his uncle had been as well [Archivio storico italiano 6 (1880), p. 320]. Cardinal Imperiali died on January 16, 1737, at the age of 85, and was buried in S. Agostino in Rome [V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma V, p. 103, no. 307] . (His librarian was Giusto Fontanini)

- Annibale Albani (aged 47) [of Urbino]. Cardinal Priest of S. Clemente (1722-1730); Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Cosmedin (1715-1722), previously Cardinal Deacon of S. Eustachio (1712-1716). Archpriest of the Vatican Basilica [from 1712; he still held the post in 1747: Andreucci, De vicariis basilicarum Urbis 2nd ed. (Rome 1854), p. 85; Henry Stuart Cardinal York held the position on November 14, 1751. It is likely that Cardinal Albani was Archpriest for life]. Governor of Frascati and Castelgandolfo (1712-1726). Cardinal Camerlengo (1719-1747). Orator of the Emperor Charles VI before the Holy See (1720-1748). Doctor of Theology. Doctor of Law. Died October 21, 1751. Promoted Cardinal BIshop of Sabina immediately after the Conclave (1730-1743).

- Ludovico Pico della Mirandola (aged 71). Cardinal Priest of S. Prassede (1728-1731). Died August 10, 1743)

- Gianantonio Davia (De Via) (aged 69) [Bologna]. Cardinal Priest of S. Pietro in Vincoli (1725-1737). Died January 11, 1740.

- Antonio Felice Zondadari (aged 74) [Siena]. Cardinal Priest of S. Balbina (1715-1731). Died November 23, 1737.

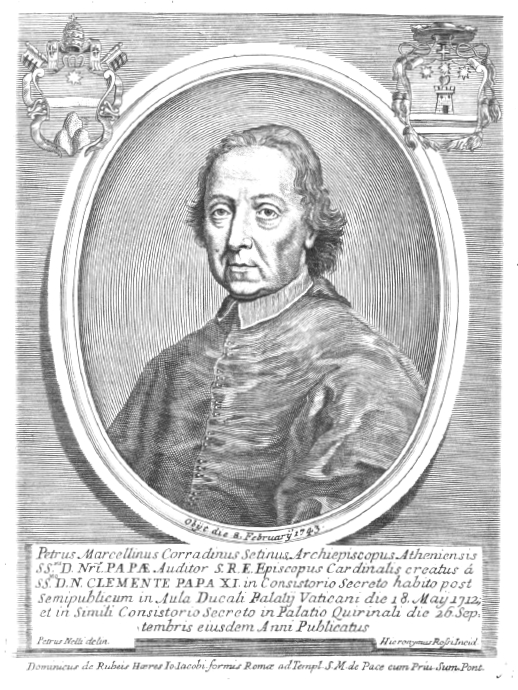

- Pier Marcellino Corradini (aged 71). Cardinal Priest of S. Maria in Trastevere (1726-1734), with S. Giovanni a Porta Latina in commendam. Died February 8, 1743.

- Armand Gaston Maximilien de Rohan de Soubise (aged 55) [France], Cardinal Priest of Sma Trinità al Monte Pincio (1721–1749). Bishop of Strasbourg (1704-1749).

- Curzio Origo (aged 69) [Romanus]. son of Marchese Gaspare Origo and Maria Laura de Palumbaria. Cardinal Priest of S. Eustachio (1726-1737), previously Cardinal Deacon of S. Eustachio (1716–1726). He began his ecclesiastical career as Protonotary Apostolic. Named Auditor of the Segnatura by Innocent XII in 1690. In 1705 he was a member of Cardinal Tanara's legation to San Marino, along with Msgr. Annibale Albani [Padiglione, Dizionario bibliografico e historico della Repubblica di San Marino (Napoli 1872), 263]. Legate in Bologna at the time of the Sede Vacante of 1724 [Cingoli, p. 324]. Died March 18, 1737.

- Melchior de Polignac (aged 68) [Chateua de la Ronte, near Puy en Vélay, Auvergne, France], son of Louis Armand, Vicomte de Polignac, and Jacqueline de Roure. Cardinal Priest of S. Maria degli Angeli (1724–1741) He studied at the College de Harcourt in Paris, where an enthusiastic professor turned him into a Cartesian. His thesis at the Sorbonne was on pious kings of Judah who took away the high places. At the age of 28, he was a conclavist of Cardinal de Bouillon from August to October, 1689 [Crescimbeni Vite degli Arcadi V, 206]. Member of the Académie Française (1704), taking the chair of Bossuet. Auditor of the Rota (1706-1709). Created Cardinal deacon in 1712, but he did not receive a deaconry until 1724 (and then only from September to November). French Chargè d'affaires before the Holy See (1724-1732). Archbishop of Auch (1726–1741). In 1728 he was granted the Collar of the Order of the Holy Spirit. Member of the Arcadian Academy from 1724 [biography in Crescimbeni, Vite degli illustri Arcadi V, 203-224]

- Benedetto Odescalchi Erba (aged 50) [Milan], son of Marchese Antonio Erba-Odescalchi and Teresa Turconia, great-grand-niece of Pope Innocent XI. Cardinal Priest of SS. XII Apostoli (1725–1740). He was taken to Rome at the age of eleven, and enrolled in the Collegio Romano. He became a lawyer. He entered the Curia at the beginning of the reign of Clement XI, and was soon appointed Pro-Legate of Bologna, where he became a friend of Vincenzo Gotti, the future cardinal. Nuncio of Clement XI to Poland until 1712. Archbishop of Milan (1712-1736). Died December 13, 1740, and buried in the Carmelite church of S. Giovanni.

- Damianus Hugo de Schönborn Buchaim (aged 53) [Germanus, born in Mainz, where his uncle was Elector], Cardinal Priest of S. Maria della Pace (1726–1743). Bishop of Speyer (1719-1743).

- Henri Thiard de Bissy (aged 72) [France], Cardinal Priest of Ss. Quirico e Giulitta (1721–1730). Bishop of Meaux (Meldensis) (1705-1737).

- Innico Caracciolo (aged 87), Bishop of Aversa (1697-1730). Cardinal Priest of S. Tommaso in Parione (1716–1730). Died September 6, 1730.

- Nicolò Gaetano Spinola (aged 71) [Genoese, but born and raised in Spain. Son of Giovanni Domenico, Conte di Pezzuola,.he was sent to Rome as a youth, and raised by his uncle, Cardinal Giovanni Battista Spinola]. Cardinal Priest of Ss. Nereo ed Achilleo (1725–1735) Auditor of the Apostolic Camera. Nuncio in Poland (1707-1715). Previously Clericus of the Apostolic Camera.

- Giberto Bartolomeo Borromeo [Milan]. Cardinal Priest of S. Alessio. Bishop of Novara (1717-1740), and titular Latin Patriarch of Antioch Syriae (1711-1717 and in commendam to 1740). Praepositus cubiculae of Clement XI. Protonotarius Apostolicus de numero participantium. After the death of Clement XI, he retired to his diocese, which he administered, and collected books.

- Giulio Alberoni (aged 65) [Piacenza]. Cardinal Priest of S. Crisogono (1728–1740). Died June 26, 1752.

- Giorgio Spinola (aged 62) [Genoa]. Cardinal Priest of S. Agnese fuori le mura (1721–1734), then Cardinal Bishop of Palestrina. Benedict XIII had appointed him Legate in Bologna, from which he arrived in Rome on March 7, two days after the Conclave had begun. Former Apostolic Nuncio in Vienna (1713-1719). Nuncio to Poland (1710). Nuncio to the Duke of Florence. Former Governor of Viterbo (1699), and before that Centumcellae. Died January 17, 1739. His funeral monument is in S. Salvatore delle Coppelle [V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma VIII, p. 506 no. 1176].

- Cornelio Bentivoglio de Aragonia (aged 61) [Ferrara]. Cardinal Priest of S. Cecilia (1727-1732) Nuncio in France (1712-1715).

Luis Antonio Belluga y Moncada (aged 67) [Motril, Spain], Cardinal Priest of S. Prisca (1726–1737), previously Cardinal Priest of S. Maria in Traspontina (1721-1726). Studied in Granada and Seville. Doctor in Theology, Sevilla (1686). In 1687 he became a Canon at Zamora, and then Prebend in the Cathedral of Cordoba. In Cordoba he introduced the Congregation of the Oratorians of S. Philip Neri. He supported the party of Philip V de Bourbon in the War of the Spanish Succession. In gratitude, Philip named him Bishop of Cartagena. He was consecrated on April 19, 1705. In 1706 he was named Viceroy of Valencia and Captain General of Murcia. On November 29, 1719, Pope Clement XI named him cardinal. He had sworn a personal vow not to accept any office that was incompatable with residence in his diocese, but the Pope dispensed him. In 1724 he resigned his bishopric and travelled to Rome, in time for the Conclave of 1724 [Guarnacci II, 340, erroneously states that he was absent; his conclavists and his dapifer are granted conclave benefits]. He established his residence in Rome, and sought to live a life of prayer and meditation. He was a member of the SC of Bishops and Regulars, of the Council, of Rites, and of Ecclesiastical Immunity (a congregation founded on June 22, 1622, by Urban VIII, taking over tasks previously dealt with by the SC on Bishops (founded by Sixtus V on January 22, 1588). He was offered the Archbishopric of Toledo, but he refused. Protector of Spain before the Holy See. He died in Rome on February 22, 1743, at the age of 80, and was buried in the Chiesa Nuova (S. Maria in Vallicella) [V. Forcella Inscrizione delle chiese di Roma IV, p. 179, no. 449]. [Biografia eclesiastica 14 (Madrid 1862), 239-240].

Luis Antonio Belluga y Moncada (aged 67) [Motril, Spain], Cardinal Priest of S. Prisca (1726–1737), previously Cardinal Priest of S. Maria in Traspontina (1721-1726). Studied in Granada and Seville. Doctor in Theology, Sevilla (1686). In 1687 he became a Canon at Zamora, and then Prebend in the Cathedral of Cordoba. In Cordoba he introduced the Congregation of the Oratorians of S. Philip Neri. He supported the party of Philip V de Bourbon in the War of the Spanish Succession. In gratitude, Philip named him Bishop of Cartagena. He was consecrated on April 19, 1705. In 1706 he was named Viceroy of Valencia and Captain General of Murcia. On November 29, 1719, Pope Clement XI named him cardinal. He had sworn a personal vow not to accept any office that was incompatable with residence in his diocese, but the Pope dispensed him. In 1724 he resigned his bishopric and travelled to Rome, in time for the Conclave of 1724 [Guarnacci II, 340, erroneously states that he was absent; his conclavists and his dapifer are granted conclave benefits]. He established his residence in Rome, and sought to live a life of prayer and meditation. He was a member of the SC of Bishops and Regulars, of the Council, of Rites, and of Ecclesiastical Immunity (a congregation founded on June 22, 1622, by Urban VIII, taking over tasks previously dealt with by the SC on Bishops (founded by Sixtus V on January 22, 1588). He was offered the Archbishopric of Toledo, but he refused. Protector of Spain before the Holy See. He died in Rome on February 22, 1743, at the age of 80, and was buried in the Chiesa Nuova (S. Maria in Vallicella) [V. Forcella Inscrizione delle chiese di Roma IV, p. 179, no. 449]. [Biografia eclesiastica 14 (Madrid 1862), 239-240]. - Mihály Frigyes Althan (aged 47) [German], Cardinal Priest of S. Sabina (1720–1734). Bishop of Vác (1718-1734).

- Alvaro Cienfuegos Villazón, SJ [Aguerra, diocese of Oviedo], Cardinal Priest of S. Bartolomeo all’Isola (1721–1739). Archbishop of Monreale (1725-1739). Minister Plenipotentiary of the Emperor to the Papal Court. Co-Protector of Germany and of the Hereditary Domains of the House of Austria.

- † Bernardo Maria de' Conti, OSB.Cassin. (aged 66), son of Carlo, Duke of Poli, and Isabella Muti. Cardinal Priest of S. Bernardo alle Terme (1721–1730); created June 16, 1721. Major Penitentiary. Died during the Conclave on April 23, 1730, apparently of a stroke (apoplexy) [Guarnacci II, 396]. Brother of Innocent XIII. He entered the Monastery of St. Paul's a few days before his 16th birthday. After getting his training in philosophy and theology, he travelled several monasteries in the Po Valley, and settled finally in Parma, where his family had property. In 1700 he returned to Rome to the Monastery of S. Callisto, but was elected Prior of the monastery of his order in Assisi. He was then elected Prior of his old Monastery of St. Paul's in Rome, and finally Abbot of Farfa. In 1710 Clement XI named him Bishop of Terracina (Anxur) (1710-1720) [Gams, p. 732]. He resigned the bishopric, however, due to ill health, and retired to the home of his brother, the Duke of Poli. He was named Cardinal by his brother, and Protector of all the Order of St. Benedict. He was given a seat on all of the Congregations of the Roman Curia. He chose to reside in the Monastery of S. Bartolomeo all' Isola.

- Giovanni Battista de' Altieri (aged 56) [Roman]. Cardinal Priest of S. Matteo in Merulana (1724–1739).

- Vincenzo Petra (aged 67) [Naples], Cardinal Priest of S. Onofrio (1724–1737). Prefect of the S.C. of Propaganda Fide (1727-1747).

- Prospero Marefoschi (aged 76) [Macerata], Cardinal Priest of S. Silvestro in Capite (1728–1732). Vicar General of Rome (1726-1732).

- Niccolò Coscia (aged 49) [of Benevento], Cardinal Priest S. Maria in Domnica pro hac vice Title (1725–1755). Archbishop of Benevento (1730-1731). Died February 8, 1755. He claimed to be suffering from podagra, which inhibited him from carrying out the orders of the Sacred College [Lioni, 20: letter of March 11].

- Angelo Maria Quirini, OSB.Cas. (aged 50) [Venice], Cardinal Priest of S. Marco (1728–1743). Archbishop-Bishop of Brescia (1727-1755).

- Niccolò Maria Lercari (aged 54) [Genoa], Cardinal Priest of SS. Giovanni e Paolo (1726–1743). Secretary of State (1726-1730).

- Prospero Lambertini (aged 55) [Bologna], Cardinal Priest of S. Croce in Gerusalemme (1728–1740). Archbishop-Bishop of Ancona (1727-1731); later Archbishop of Bologna (1731-1754) and Bishop of Rome (1740-1758)..

- Francesco Antonio Finy (aged 60) [Minerviensis]. Cardinal Priest of S. Sisto (1729–1738).

- Sigismund von Kollonitsch (aged 53) [German], Archbishop of Vienna (1722-1751). Named a Cardinal Priest in November, 1727.

- Philip Ludwig von Sinzendorf (aged 30) [German], Bishop of Györ (1726-1732). Cardinal Priest from November, 1727. Cardinal Priest of S. Maria sopra Minerva (1730–1747).

- Vincenzo Ludvico Gotti, OP. (aged 65) [Bologna]. Cardinal Priest of S. Pancrazio (1728–1738). He was a member of the Arcadian Academy [biography by Tomaso Agostino Ricchini, in Crescimbeni, Vite degli illustri Arcadi V, 103-114]

- Leandro Porzia, OSB.Cas. (aged 56) [Foroiuliensis], Cardinal Priest of S. Callisto (1728–1740). Bishop of Bergamo.

- Pierluigi Carafa (aged 52) [Naples], a member of the family of the Princes of Belvedere. Cardinal Priest of S. Lorenzo in Panisperna (1728–1737). Named Privy Chamberlain (Cameriere segreto) to Innocent XII, to whom he was related, in 1699. Clement XI appointed him Vice-Legate in Urbino which he governed himself for three years in the absence of Cardinal Marcello d'Aste. Cleric of the Apostolic Camera in 1708; promoted to Presidente delle strade in 1712. Secretary of the SC de propaganda fide, then Secretary of the SC of Bishops and Regular Clergy. Created a cardinal by Benedict XIII on September 20, 1728. He became Bishop of Ostia and Dean of the Sacred College of Cardinals in 1751. He died on December 15, 1755, at the age of 79.

- Giuseppe Accoramboni (aged 57) [Spoleto], Cardinal Priest of S. Maria in Traspontina (1728–1740). Archbishop-Bishop of Imola (1728-1739).

- Camillo Cibo (aged 48) [Massa Carrara]. Cardinal Priest of S. Stefano al Monte Celio (1729–1731). Died January 12, 1743.

- Francesco Scipione Borghese (aged 32) [Roman]. Cardinal Pirest of S. Pietro in Montorio (1729–1732). Died June 21, 1759.

- Vincenzo Maria Ferreri, OP (aged 47) [Niciensis], Cardinal Priest of S. Maria in Via (1729–1742). Bishop of Vercelli (1729-1742).

- Alamanno Salviati (aged 60) [Florentinus]. Cardinal Priest without title; named Cardinal Priest of S. Maria in Ara Coeli (1730–1733.) by the new Pope on July 24, 1730.

- Lorenzo de' Altieri (aged 58) [Romanus]. Created Cardinal at the age of 19. Cardinal Deacon of S. Agata alla Suburra (1718–1730). Died August 3, 1741. Cousin of Clement X, nephew of Cardinal Paluzzo Paluzzi Altieri degli Albertoni.

- Carlo Colonna (aged 64) [Romanus], son of Lorenzo, Duke of Paliano, Grand Constable of the Kingdom of Naples, Prince of Castiglione, etc.Grandee of Spain, First Class; and Maria Mancini.. Cardinal Deacon of S. Angelo in Pescheria (1715–1730)

- Fabio Olivieri (aged 71) [Pesaro], Cardinal Deacon of SS. Vito, Modesto e Crescenzia (1715–1738). Secretary of Briefs.

- Carlo Marini (aged 63) [Genoa], Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Aquiro (1716–1738). Legate in Romagna.

- Alessandro Albani (aged 37) [Urbino]. son of Orazio Albani, brother of Clement XI, and Maria Bernardina Hondedea of Pesauro. Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Cosmedin (1722–1741). A soldier in his youth, he commanded a troop of light armed horse. His uncle Clement XI made him a Cleric of the Apostolic Camera. He was sent in 1720 as Nuncio to the Emperor to conclude important negotiations; on the death of the Pope, he returned to Rome. Innocent XIII named him a cardinal, on July 16, 1721, at the age of 28, recollecting that Alessandro's uncle had made him a cardinal. Protector of the Kingdom of Sardinia. Imperial Agent and Co-Protector of the Empire at the Papal Curia (with Cardinal de Judice, until his death in 1725); Protector of the German-Hungarian College in Rome, Protector of the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem,

- Alessandro Falconieri (aged 73) [Romanus]. Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria della Scala (1724–1734).

- Niccolò del Giudice (aged 69) [Naples], of the family of the Princes of Collemare and Dukes of Giovenazzo. Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria ad Martyres (1725–1743). appointed Protonotario Apostolic by Innocent XII in 1699; he became a Cleric of the Apostolic Camera, and in 1701 was named to the post of Presidente delle strade in the Apostolic Camera. Clement XI made him Presidente della gracia in the Apostolic Camera, and in 1716 Praefectus Sacri Palatii Apostolici. Benedict XIII named him a cardinal on June 11, 1725. He died in Rome on January 30, 1743, at the age of 83.

- Antonio Banchieri (aged 63) [Pistoria]. Cardinal Deacon of S. Nicola in Carcere (1728–1733) Secretary of State of His Holiness (1730-1733).

- Carlo Collicola (aged 47) [Spoleto]. Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Portico (1728–1730) Died October 20, 1730.

- Agostino Cusani (aged 84) [Milan], Bishop of Pavia. Cardinal Priest of S. Maria del Popolo [created May 18, 1712] Died December 27, 1730

- Nuno da Cunha e Ataïde [Portugal], son of Luis, Conte de Pavolide. Cardinal Priest of S. Anastasia (1721–1750) [Created May 18, 1712, on the demand of King John V]. Doctor of Canon Law. Bishop of Targa (1705-1712). Inquisitor General in Portugal.

- Wolfgang Hannibal von Schrattembach (aged 69) [Germany], Cardinal Priest of S. Marcello [created May 18, 1712, at the request of the Emperor] Bishop of Olomouc (1711-1738),

- Imre Csáky [Hungary], Cardinal Priest of S. Eusebio. His family claimed descent from an 8th century king of the Huns; his father Estvan was Regiae Curiae Judex in Hungary. Cardinal Priest without titulus (died August 28, 1732). Archbishop of Kalocsa and Bács in Hungary (1710-1732) [Gams, 372], previously bishop of Varadinum (Nagy-Várad) (1702), Abbot of Waradin (Várad); Canon of Eger. Educated at the Collegium Romanum [Gams, 382] [created July 12, 1717]

- Carlos de Borja-Centelles y Ponce de León (aged 66) [Spain], Cardinal Priest of S. Pudenziana (1721–1733); created November 29, 1719] Patriarch of the West Indies (1708-1733).

- Léon Potier de Gesvres (aged 73) [France]. [created November 29, 1719, no title assigned] Archbishop of Bourges (1694–1729).

- Thomas Philip Wallrad d'Hénin-Liétard d'Alsace-Boussu de Chimay (aged 50) [Netherlands], Cardinal Priest of S. Cesareo in Palatio pro hac vice Title (1721–1733). [created November 29, 1719]. Archbishop of Mechlin (1715-1759). He had his doctors swear an affidavit for the Emperor, in which he excused himself from attendance at the Conclave on the grounds of illness [La Storia degli anni 1730., e 1731. , p. 93].

- José Pereira de la Cerda [Portugal], Cardinal Priest of S. Susanna (1721–1738); created November 29, 1719]. Bishop of Faro [Faraoniensis] (1716-1738).

- André Hercule de Fleury [France], Counselor of State of France. [created September 11, 1727]. He was forbidden by the King of Portugal to go to Rome for the Conclave of 1730 [La Storia degli anni 1730., e 1731. , p. 93-94].

- Diego de Astorga y Céspedes (aged 63) [Spain], Archbishop of Toledo (1720-1734). [created Cardinal on November 26, 1727]

- João da Motta e Silva [Portugal]. [created November 26, 1727] Died October 4, 1747, without having visited Rome or received his red hat. He was forbidden by the King of Portugal to go to Rome for the Conclave of 1730 [La Storia degli anni 1730., e 1731. , p. 93-94].

Factions

The Conclave of 1730 was long, contentious, and sometimes disgraceful. It lasted four and a half months. At the opening, on Sunday, March 5, there were twenty-six cardinals in attendance; by the time of the election, there were fifty-six. The oration de pontifice eligendo was spoken by Msgr. Giacomo Lanfredini, Secretary of the SC of the Council; he became a cardinal on March 24, 1734.

The conclave was especially difficult because the many factions were small and not firmly fixed in their preferences. The Camerlengo, Cardinal Annibale Albani led the creature of Pope Innocent XI. His younger brother, Alessandro Albani, led a small party of "Savoyards" or "Sardinians". There was also an Imperial party (several of whose members, Schrattembach, Csaky, and d'Hénin-Liétard d'Alsace-Boussu de Chimay, did not attend), and a French party (though Polignac [portrait at right] was saying that the French cardinals would not attend because it was pointless; he also stated that the French King had not authorized a veto), allied with the Spanish. The Zelanti were ever present, but vacillated constantly in their voting patterns. In early voting, the fortunes of Cardinals Tommaso Ruffo (Cardinal Bishop of Palestrina), Antonio Felice Zondadari, and Antonio Banchieri (former Governor of Rome, and ex-Vice-Chancellor) rose and fell. The only active pratticà seemed to be that for Cardinal Imperiali [Lioni, 18]. The Cardinals were greatly concerned about the attendance of the Portuguese cardinals. They sent a messenger to Spain, to the Nuncio Msgr. Alessandro Aldobrandini, Archbishop of Rhodes, instructing him to send an official to Lisbon to discover the situation of the Portuguese Cardinals with respect to the Conclave; they were afraid that the King of Portugal might concoct an excuse not to recognize the canonical election of a new pope. This was followed by a letter to the Nuncio, Msgr. Giuseppe Firrao (Nuncio to Portugal, September 28, 1720—December 11, 1730), urging him to use every means to persuade the Portuguese king to permit his cardinals to attend the Conclave. Cardinal João da Motta e Silva was specifically invited to come to Rome to help adjust the differences which had arisen between the Court of Rome and the Court of Lisbon [La Storia degli anni 1730., e 1731. , p. 96-97]. The talk in Rome was that the Spanish cardinals were likely to arrive on the 15th or 16th.

The conclave was especially difficult because the many factions were small and not firmly fixed in their preferences. The Camerlengo, Cardinal Annibale Albani led the creature of Pope Innocent XI. His younger brother, Alessandro Albani, led a small party of "Savoyards" or "Sardinians". There was also an Imperial party (several of whose members, Schrattembach, Csaky, and d'Hénin-Liétard d'Alsace-Boussu de Chimay, did not attend), and a French party (though Polignac [portrait at right] was saying that the French cardinals would not attend because it was pointless; he also stated that the French King had not authorized a veto), allied with the Spanish. The Zelanti were ever present, but vacillated constantly in their voting patterns. In early voting, the fortunes of Cardinals Tommaso Ruffo (Cardinal Bishop of Palestrina), Antonio Felice Zondadari, and Antonio Banchieri (former Governor of Rome, and ex-Vice-Chancellor) rose and fell. The only active pratticà seemed to be that for Cardinal Imperiali [Lioni, 18]. The Cardinals were greatly concerned about the attendance of the Portuguese cardinals. They sent a messenger to Spain, to the Nuncio Msgr. Alessandro Aldobrandini, Archbishop of Rhodes, instructing him to send an official to Lisbon to discover the situation of the Portuguese Cardinals with respect to the Conclave; they were afraid that the King of Portugal might concoct an excuse not to recognize the canonical election of a new pope. This was followed by a letter to the Nuncio, Msgr. Giuseppe Firrao (Nuncio to Portugal, September 28, 1720—December 11, 1730), urging him to use every means to persuade the Portuguese king to permit his cardinals to attend the Conclave. Cardinal João da Motta e Silva was specifically invited to come to Rome to help adjust the differences which had arisen between the Court of Rome and the Court of Lisbon [La Storia degli anni 1730., e 1731. , p. 96-97]. The talk in Rome was that the Spanish cardinals were likely to arrive on the 15th or 16th.

On Tuesday evening, the 7th of March, Cardinal Giorgio Spinola arrived in Rome from his Legation in Bologna. He was immediately met by the Camerlengo Cardinal Albani's Auditor with profuse compliments and avowals of the trust that the Albani family placed in Cardinal Spinola. Cardinal Spinola replied with equal effusiveness, and remarked that, just as in the Conclave of 1721, he hoped to be included in the "secret" of Cardinal Albani's pratticà—that is to say, he hoped to be Albani's second-in-command [Lioni, 19].

The First Scrutiny took place on March 6, but it went slowly and was purely for the sake of formalities. Only a minority of the Cardinals was present, and none of the representatives of the major powers wished to proceed until their Cardinals arrived and they had had an opportunity to receive fresh instructions, and perhaps an Ambassador Extraordinary, from their government. Cardinal Cienfuegos, in fact, announced to the Cardinals that five cardinals of the German party were coming to the Conclave, and that it was the request of the Emperor Charles VI that the Conclave should await their arrival [Lioni, 18].

On March 22, Cardinal Ruffo arrived from his Legation in Ferrara, and entered Conclave on the same day.

On April 1, the Ambassador Extraordinary of the Emperor, Conte Collalto, arrived in Rome, and took up residence in Cardinal Cienfuegos' palazzo. By April 3, there were fifty cardinals voting in the scrutinies. Around the middle of April, the favorite in the scrutinies seemed to be Cardinal Ruffo.

On April 23, Cardinal Conti died in the Conclave, of an attack of apoplexy.

On April 24, Cardinal Barberini managed to achieve 32 votes in the Scrutiny, many of them departing from the party of Cardinal Coscia. On the same day a courier arrived from Madrid, with dispatches for the Spanish Ambassador, the Marquis de Monteleone. Among them was the exclusiva to be used against Cardinal Giuseppe Renato Imperiali (Wahrmund, 226; portrait at left). When Cardinal Imperiali came within one vote of success, the Veto (exclusiva) was interposed by Cardinal Cornelio Bentivoglio in the name of the King of Spain. On June 11 Cardinal Gianantonio Davia of Bologna, Cardinal Priest of S. Pietro in Vincoli, obtained twenty-nine votes, but he could not reach the thirty-six votes needed to elect (Montor, 11).

On April 24, Cardinal Barberini managed to achieve 32 votes in the Scrutiny, many of them departing from the party of Cardinal Coscia. On the same day a courier arrived from Madrid, with dispatches for the Spanish Ambassador, the Marquis de Monteleone. Among them was the exclusiva to be used against Cardinal Giuseppe Renato Imperiali (Wahrmund, 226; portrait at left). When Cardinal Imperiali came within one vote of success, the Veto (exclusiva) was interposed by Cardinal Cornelio Bentivoglio in the name of the King of Spain. On June 11 Cardinal Gianantonio Davia of Bologna, Cardinal Priest of S. Pietro in Vincoli, obtained twenty-nine votes, but he could not reach the thirty-six votes needed to elect (Montor, 11).

Shortly after the events of April 24, three cardinals—Fini, Porzia, and Ruffo—requested and received permission from the Cardinals to retire from the Conclave for the sake of their health. They were back in a few days.

Around the first of May, two of the factions, the creature of Clement XI led by Cardinal Albani, and the creature of Benedict XIII , decided to attempt to pool their resources on a single candidate acceptable to both; they settled on Cardinal Davia, but they were unable to muster a sufficient number of votes in the scrutinies. When Davia failed, the group put up the name of Cardinal Corsini. Suddenly, he had thirty-one votes [La Storia degli anni 1730., e 1731., p. 96].

In the second week of May there was a series of earthquakes in Italy. On the 14th, news reached the Conclave that the town of Norcia had nearly been levelled by a quake and 400 people killed. On the 15th, Rome itself felt a quake. Several days later Sulmona had an earthquake as severe as Norcia's. On the 18th it was the turn of the town of Lionessa. The tension was high, both inside and outside the Conclave. Many saw the earthquakes as evidence of God's displeasure at the failure of the Cardinals to produce a new Pope.

On May 20, the Cardinals received a reply to their efforts to get the Portuguese cardinals to come to the Conclave. The Portuguese expressed their regrets that they were unable to attend, without expressing the real causes. News also came that the Patriarch of Lisbon had taken it upon himself to deal personally with the King of Portugal in order to diminish some of the friction between Lisbon and Rome.

On the 16th of June, Cardinal Pietro Marcellino Corradini [portrait at right], the pro-Datary of Benedict XIII, reached thirty votes (Montor, 11). Nexty day he still needed only three votes. Bentivoglio, who had already cast the Spanish Veto, announced that he and his Spanish-leaning colleagues would leave Rome if Corradini were to be elected [La Storia degli anni 1730., e 1731., p. 99-100]. Cardinal Cienfuegos, who had instructions from the Emperor to exclude Corradini, set to work to overcome the distaste among the Imperialist faction against Cardinal Corsini as an alternative to Corradini.

On July 4, the name of Cardinal Corsini was taken up again, this time seriously. He had been a cardinal since 1706, The Zelanti were particularly favorable. The Spanish, French and Germans were agreeable. On the 9th, it became clear that Corsini would be elected, and the fifty-two Cardinals then enclosed in Conclave let it be known to those who were outside the Conclave due to illness that now was the time to return for the final vote [La Storia degli anni 1730., e 1731., p. 100-101].

Lorenzo Cardinal Corsini, aged seventy-nine, was finally chosen with fifty-two votes on July 12, taking the name Clement XII. He named Cardinal Banchieri as his Secretary of State on July 12. Cardinal Petra was confirmed in the post of Major Penitentiary on the 18th; after the death of Cardinal Conti during the Conclave, the Cardinals had elected him pro-Penitentiary. On August 14, he named his nephew Neri Maria Corsini a cardinal, though the fact was an official "secret", since he had been created in petto and was not proclaimed until December. Cardinal Corsini became Secretary for Memorials.

On the evening before the Cornation the sum of 4000 scudi was distributed to the poor, at the rate of one paolo per head, to each person who was assembled at the Papal Palace for the purpose. Clement XII was crowned in the Vatican Basilica on July 16, 1730, and on November 19, he took possession of the Lateran Basilica, his cathedral church where his episcopal throne was located [La Storia degli anni 1730., e 1731., p. 117]. The new pro-Datary was Msgr. Antonio Saverio Gentili, who was named a Cardinal on September 24, 1731. The new Maggiordomo was Msgr. Trioiano d' Aquaviva, titular Archbishop of Larissa in Thessaly; he was named a cardinal on October 1, 1732. The new Maestro di Camera was Msgr. Lazzero Pallavicini, titular Archbishop of Thebes.

On August 1, 1730, in response to the many complaints about the maladministration which had taken place in the reign of Benedict XIII, the new Pope Clement XII created a special Criminal Congregation, called the Congregatio de nonnullis, which was to investigate in particular charges of simony on the part of the ministers of the deceased pontiff, and frauds perpetrated against the Apostolic Camera. Cardinals Banchieri, Corradini, Imperiali, Pico della Mirandola, and Porzia were named to the Congregation, with Msgr. Domenico Cesare Fiorello, Referendary of the Two Signatures, as Secretary [La Storia degli anni 1730., e 1731., p. 106-113; the text of the motu proprio is given at pp. 107-110]. Cardinal Coscia was, of course, one of the principal targets of investigation. Sgr. Prati of Benevento was arrested immediately and sent to the Castel S. Angelo, while his goods were impounded and inventoried. All of the gold and silver in the house of Cardinal Finy was taken by the Congregation; Fini had been pro-Auditor of the Apostolic Palace and was one of the Palatine cardinals. Msgr. Santa Maria, the Majordomo of Benedict XIII, had his appointment as Consultor of the Holy Inquisition revoked. Abbot Capocaccia was hauled off to prison. Sealed chests which had been placed on deposit by a Beneventan named Secretis in the house of a friend before fleeing from Rome, were opened on orders of the Congregation, and were found to contain 10,000 scudi and other valuables, all of which were confiscated. The people of Benevento poured forth their complaints against Cardinal Coscia. The Pope asked Duke Strozzi to surrender the person of the Cardinal, but he declined, while Coscia refused to resign his bishopric of Benevento (as he had been advised by Cardinals Cienfuegos and Salviati). Pope Innocent retaliated by appointing a Vicar General for Benevento, who was ordered to reside in Benevento, and by taking into his own hands the appointments to benefices in the diocese of Benevento without consulting Cardinal Coscia. Monsignor Nicolò Negroni, the Treasurer General of the Apostolic Camera, was ordered to repay 4,000 scudi which had been embezzled from the Apostolic Camera.

Bibliography

Relazione distinta della solenne Coronazione di Nostro Signore Papa Clemente XII ... Corsini di Firenze (Roma 1730).

For the Conclave of 1730, see: Alexis Francois Artaud de Montor, Histoire des souverains pontifes (Paris 1851) 10-12. Giuseppe de Novaes, Elementi della storia de' sommi pontefici da San Pietro sino al ... Pio Papa VII third edition, Volume 13 (Roma 1822) 160-165. G. Moroni, Dizionario di erudizione storico-ecclesiastica Vol. 14 (Venezia 1842) 71, in a strange act of self-censorship, is completely silent about the proceedings. Ferdinando Petruccelli della Gattina, Histoire diplomatique des conclaves Volume IV (Bruxelles 1864), 56-101. Girolamo Lioni, Storia di un conclave. Lettere di Mons. Girolamo Conte Lioni (Venezia: Istituto Coletti 1878) [Lioni was dapifer of Cardinal Leandro Porzia: Bullarium Romanum Turin edition 23, 39].

La Storia degli anni 1730., e 1731. (Amsterdam: A spese di Francesco Pitteri n.d.) pp. 82-117.

"Corrpspondenza Epistolare fra il Conte di Collalto Ambasciatore Imperiale Straordinario in Roma, ed il Conte Carlo Borromeo Plenipotenziario Imperiale in Italia, residente in Milano (1730)," in Felice Calvi, Curiosità storiche e diplomatiche del secolo decimottavo (Milano: Antonio Vallardi 1878), pp. 1-27.

Joannes Rudolphus Conlin, Roma Sancta, sive Benedicti XIII. Pontificis Maximi et Eminentissimorum et Reverendissimorum S. R. E. Cardinalium viva virtutum imago ... qui ultimo conclavi anno 1724 interfuere, praeter eos qui a Sanctissimo Patre Benedicto XIII. neo-denominati fuere.... (Augustae Vindelicurum 1726). Mario Guarnacci, Vitae et Res Gestae Pontificum Romanorum et S. R. E. Cardinalium a Clemente X usque ad Clementem XII Tomus Secundus (Romae 1751).

For the career of Cardinal Lorenzo Corsini, see Luigi Passerini, Genealogia e storia della Famiglia Corsini (Firenze: M. Cellini 1858) 157-172.

For Cardinal Coscia: S. De Lucia, Il cardinal Niccolò Coscia (Benevento 1934). G. De Antonellis, "Appunti intorno alla figura del card Niccolò Coscia," Samnium, XLIII (1970), 153-167.

On Cardinal Alberoni, see Charles Bertin, Dictionnaire des Cardinaux (1858) 205-208; Alfonso Professione, Il ministero in Spagna e il processo del Cardinale Giulio Alberoni (Torino: Clausen 1897) 293-295. P. Castagnoli, Il cardinale Giulio Alberoni vols. I-III (Piacenza-Roma 1929-32). S. Harcourt-Smith, Cardinal of Spain: The Life and Strange Career of Alberoni (1944)

P. Paul, Le Cardinal Melchior de Polignac (Paris, 1922).

'John Walton' was in fact a Prussian, Baron Philip de Stosch, who served as an espionage agent for the British Government (in particular Lord Newcastle, but also Sir Robert Walpole) in Rome: Martin Haile, James Francis Edward, the Old Chevalier (London: Dent 1907) 293-294.

An interesting 'popular' eyewitness account is given in a 'letter' of a visitor to Rome in 1730, Baron Charles-Louis de Pollnitz, The Memoirs of Charles-Lewis Baron de Pollnitz Volume II (London 1735), Letter XXVIII, pp. 13-22 (dated July 20, 1730).

W. S. Cartwright, On the Constitution of Papal Conclaves (Edinburgh 1878)

Ludwig Wahrmund , Das Ausschliessungs-recht (jus exclusivae) der katholischen Staaten Österreich, Frankreich und Spanien bei den Papstwahlen (Wien: Holder 1888) 238-239.