SEDE VACANTE

August 12, 1484—August 29, 1484

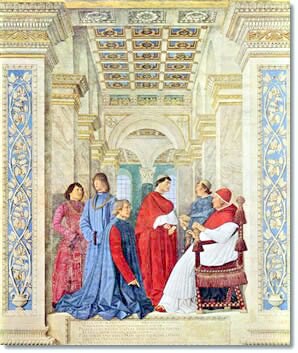

Platina is the kneeling figure,

Raffaele Riario is in blue, the future Julius II in the center.

and Pope Sixtus IV seated at the right.

No coins or medals were issued.

The Camerlengo

Raffaele Sansoni Galeotti Riario (May 3, 1461-July 9, 1521) was born at Savona, the son of Antonio Sansoni and of Pope Sixtus IV's sister Violentina. On December 10, 1477, while engaged in the study of law at the University of Pisa, he was created Cardinal Deacon of San Giorgio in Velabro by his uncle Pope Sixtus (1471-1484). He was 17. He was suspected of having had some connection with the Pazzi conspiracy, April 1478, through his uncle Count Girolamo Riario and Francesco Salviati, Archbishop of Pisa. Although he was arrested and imprisoned, his uncle the Pope had him freed and brought to Rome, where he was officially rehabilitated in consistory. Iin 1483 he became Camerlengo of the Holy Roman Church, a post he held until his death in 1521. He was loaded with benefices by Sixtus IV and Innocent VIII (1484-1492), including the administration and income of sixteen rich bishoprics (including eventually Imola, Tréguier in France, Salamanca, Osima, Cuença [1479], Viterbo [1498], and Taranto); he was also Abbot of Monte Cassino and of Cava.

Under Alexander VI, however, he was in disfavor. The greed for power and property on the part of the Borgia family made the Riarios a major target. Alexander's son Cesare coveted the holdings of the Riario family, and seized the city of Forlì and also Imola. Riario fled to France and took up his bishopric of Tréguier. On his return in September of 1503 he was appointed Bishop of Albano (in November, 1503) and was consecrated bishop on April 9, 1504 by Pope Julius II personally (another nephew of Sixtus IV). In 1507 he was promoted to the bishopric of Sabina, and on July 7, 1508, became Apostolic Administrator of Arezzo. Julius II made him Cardinal Bishop of Ostia, Porto, and Velletri on September 22, 1508. . He participated in five conclaves, including the conclaves of 1484, 1492, 1503 that elected Pius III and the one that elected Julius II, and that of 1513.

In 1517, he was involved in the conspiracy of Cardinal Alfonso Petrucci against the life of Pope Leo X (also involving Cardinals Soderini and Sauli) and was arrested (May 29) and incarcerated in the Castel S. Angelo (De Grassis, p. 48). Trials were held. The ambassadors of England, France and Spain interceded. The College of Cardinals intervened on his behalf when it appeared that he might be stripped of all of his benefices, degraded from the cardinalate, and condemned to death. On July 24, he was released from confinement and brought to the Vatican; after he swore an oath, he was admitted to the presence of the Pope (De Grassis, p. 57). After he confessed to the Pope in a lengthy speech and begged pardon, which the Pope was pleased to grant, with a huge fine, whose value changed repeatedly, and the confiscation of his palace at S. Lorenzo in Damaso (the Cancelleria). He was restored to the bishopric of Ostia at Christmas, 1518, and his fine was cancelled. He died in 'retirement' in Naples.

Paris de Grassis, Papal Master of Ceremonies, records his death in 1521 (p. 86):

Die nona julii mortuus est cardinalis Sancti Georgii, Raphael Riarius Savonensis, decanus colegii et episcopus ostiensis, qui cum esset aetatis suae anno decimonono creatus est a Sixto cardinalis, demum in vicesimo secundo camerarius in quo mansit annos viginti novem, et sic anno sexagesimoprimo vel circa obiit Neapoli. . . .

Though only twenty-three at the time of the death of Sixtus IV, Raffaele Riario attended the conclave of 1484.

Dean of the Sacred College

The Dean of the College of Cardinals in 1484 was Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere (1443-1513), nephew of the late pope and second cousin of the Cardinal Camerlengo. He would be elected Pope Julius II in the conclave of 1503.

The Masters of Ceremonies were Giovanni Burchard and Johannes Maria de Podio [Burchard, Diarium I, p. 27 Thuasne].

Death of the Pope

Pope Sixtus IV died in the Vatican Palace on the evening of Thursday, August 12, 1484, according to the Diary kept by Giovanni Burchard, the Papal Master of Ceremonies (Burchard, 3G 9T; and Eubel II, p. 47 no. 497):.

Feria quinta, 12 mensis augusti, inter horam quartam et quintam noctis, vel circa, Romae in palatio apostolico apud Sanctum Petrum in superiori camera una, supra curiam ante bibliothecam respondente, obiit sanctissimus in Christe pater et dominus noster, Dominus Sixtus divina providentia Papa quartus....

It is difficult to imagine and to overestimate the degree of fury that was unleashed against the nephews, friends and hangers-on of Sixtus IV. Indeed every Ligurian in Rome was in danger of his life. Stefano Infessura, the Senatorial secretary, a bitter enemy of the Riario family, was particularly overjoyed at the death of his enemy (Infessura, 155-160):

ita quod tam ex primo dolore, quam ex novissimo infirmatus est febre, iacuitque in lecto, et obmutuit, visusque fuit exanimis per aliquod spatium. deinde reversus, inflato gutture, duodecima die augusti, videlicet die iovis, et quinta hora noctis mortuus est Sixtus. In quo felicissimo die Deus ipse Omnipotens ostendit potentiam suam super terram, liberavit populum Christianum de manu talis impissimi et iniquissimi regis, cui nullus Dei timor, nullus regendi populi Christiani amor, nulla charitatis et dilectionis affectio, sed solum voluptas inhonesta, avaritia, pompa seu vanagloria semper et continue praecipue viguit et in consideratione fuit.

Hic, ut fertur vulgo, et experientia demonstravit, puerorum amator et sodomita fuit.... [this abuse continues for five more pages. Nepotism was the real crime, plus avarice and financial profligacy.]

On the morning of Friday, August 13, a mob attacked and completely sacked the palace of the dead pope's favorite nephew, Count Girolamo, who was in the field with the army at the seige of the Colonna stronghold of Paliano (Pontano, 38):

Alli 13 andò tutta Roma in arme et erano di molte collette per Roma, e fu messa a sacco la casa del conte Hieronimo, guasto tutto lo giardino, e levato fino alle porte et finestre, furno sachigiati li navilii et magazini a Ripa, quali erano de Genovesi, fuorono rubbate de molte cariche di robba quale se portavano da una casa ad un'altra per salvarle, e certi giovini et Spagnoli li levavano con dire che erano robbe de Genovesi...

Count Girolamo's wife Caterina managed to escape to the Castel S. Angelo, where she commandeered the fortress from the commander of the guard, and made herself safe until her husband could return. The granaries along the Tiber and two Genoese ships loaded with wine were plundered. Stefano Infessura gives the luirid details (Diario, pp. 161-164) The Genoese Hospital was destroyed. Several cardinals met at the palace of Cardinal Riario, the Chamberlain, but their efforts to restore order in Rome were futile [Pastor, 230]. On that same day the body of the deceased pope was transferred to S. Peter's and buried in his chapel [Eubel II, p. 47 no.497, from the Acta Cameralia].

On the evening of the 14th Girolamo arrived on the north side of Rome, but was ordered by the cardinals, who feared the influence of a papal nephew with an army on a free election, to remain at Ponte Molle (Milvian Bridge), but he instead joined his wife in the Castel S. Angelo. Cardinal Colonna and his supporters also returned to the city, and Girolamo Riario thought it wise to remove himself to safety with his Orsini supporters at Isola (Infessura, p. 165).

Assembly of a Conclave

On Tuesday, the 17th of August, 1484, the first of the public novendiales masses was sung by the Vice-Chancellor, Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia [Notario di Naniporto, 1089; Eubel II, p. 47 no. 497]. Only eleven cardinals attended. The Colonna faction complained that security was lax and their lives in danger, and they refused to attend the ceremonies of the novendiales (Pontano, 39). Cardinals della Rovere (San Pietro in Vincola), Cibo (Malfetta), Savelli, Colonna and Nardini (Milano) were not present. Cardinal Colonna did not enter Rome until later in the day [Notario di Naniporto, 1089]

On Wednesday, the 18th, the Franciscan Cardinal Gabriele Rangone (Bishop of Agria) arrived, raising the number of cardinals present to 13. On the 19th Cardinal Maccone appeared, on the 20th Jorge da Costa (Lisbon) (Pontano, 39).

On Sunday, August 22, the Conservatori of Rome, led by the First Conservator Vangelista de Renzo Martino, and some 200 Roman citizens met with all the cardinals in the sacristy of St. Peter's to speak about the disorders in Rome and to promise that, if the many men in arms did not guarantee the security of the cardinals so that they could elect a pope, the people of Rome themselves would do so. According to the report of Stefano Infessuri [Muratori Rerum Italicarum Scriptores III. 2, 1192; Diaria Rerum Romanorum, pp. 175-176 ed. Tommasini]:

Et quaedam officia olim annualia per Xistum vendita ad vitam, et pecunia soluta a certis civibus Romanis abdicata fuerunt, et pecunia non restituta aliis concessa, inter quae est Notariatus Appellationum et Exsequutoriatus Ripae, et aliorum similium. Sed Notariatum Appellationum incontinenti [Innocentius VIII] restituit illi qui emerat, et omnia praemissa fecit epse una cum Cardinalibus contra promissionem pacti et conventiones, quas fecerat ipse una cum aliis Cardinalibus Officialibus Romanis, et titi Populo in Basilica Sancti Petri penultima die exequiarum Xisti, dum omnes unanimiter et concorditer promiserunt inter alia, omnia Officia et Beneficia Romana concedere Romanis civibus; et ita sub fide eorum spoponderunt; contrarium cujus, ut vidistis supra, immediate gestum est. Et sic in ejus principio sequitur vestigia Xisti, etsi grave est unicuique fidem fallere, sed magis Principi..... Et ego met vidi in Palatio Conservatorum certa Capitula et promissiones, factas per praefatum Innocentium in manibus Conservatorum inter quae erat verbum hujus tenoris vel substantiae. Promitto et juro ego Innocentius Papa Octavus in praesentia omnium Dominorum Cardinalium me daturum et concessurum civibys Romanis omnia Offica aet Beneficia Urbis, Prioratus, Abbatias et alia et non consentire, neque acutoritatem praestare alicui alteri contribuantur nisi solum et dumtaxat ipsis civibus Romanis idoneis....

On Monday, the 23rd of August the cardinals decided to begin the conclave the next day, but on the 24th it proved impossible. The final Requiem Mass of the Novendiales was sung by the Cardinal of Naples. There was a riot in the Piazza della Rotonda , and several houses were attacked by partisans of the Colonna (Burchard, 11G 18T; Infessura, 168). Security arrangements were made for the entrances to the Vatican Palace, however, and an altar was prepared for the singing of the Mass of the Holy Spirit on the 25th.

On Wednesday, the 25th a truce was finally agreed to among the warring factions in Rome: Girolamo relinquished control over the Castel S. Angelo (for the sum of 4000 ducats), the Orsini retired to Viterbo, and the Colonna to Latium (Infessura, 166-167; Pontano, 40-41). On the morning of the 25th, the Mass of the Holy Spirit was sung in the presence of twenty-four cardinals by the Cardinal of San Marco, Marco Cardinal Barbo (Burchard, 25T). In the afternoon of the 25th the cardinals finally entered the Conclave. Burchard (p. 15, 27-29T) provides the names of all of the cardinals and their conclavisti. The Cardinals were Borgia, Oliviero Caraffa, Marco Barbo, Giuliano della Rovere, G.-B. Zeno, Stefano Nardini, Giovanni Arcimboldi, G.-B. Cibò, Philibert Ugonetti (Hugonet of Macon), Giovanni Michaeli (Michiel), Jorge da Costa, Girolamo Basso della Rovere, Gabriele Rangoni, Domenico della Rovere, Juan de Aragon, Pietro Foscari, Giovanni de' Conti, Juan de Margarit, Giovanni Schiaffinati, Francesco Piccolomini, Raffaele Riario, G.-B. Savelli, Giovanni Colonna, G.-B. Orsini, and Ascanio Maria Sforza Visconti. Seven cardinals did not participate. A similar list is provided by the archives of the Ceremonial Congregation (Bourgin, 314). Both lists contain twenty-five names. After lunch, the cardinals and the conclavisti met separately to make necessary arrangements for the details of the conclave.

The Cardinals

- Giuliano della Rovere, Suburbicarian Bishop of Ostia e Velletri [Eubel II, p. 46, no. 473], previously Bishop of Sabina (1479-1483) [Eubel II, p. 42 no. 404], and before that Cardinal Priest of S. Petri in vinculis (1471-1479). Bishop of Bologna (1483-1502), Administrator of Avignon, Dean of the Sacred College of Cardinals. "S. Pietro in Vincoli" Major Penitentiary. Nephew of Sixtus IV.

- Rodrigo de Borja y Borja (aged 52), Suburbicarian Bishop of Porto e Santa Rufina, Administrator of Cartagena and of Valencia. Archpriest of the Liberian Basilica (S. Maria Maggiore). Vice-Chancellor. Nephew of Callistus III. On May 15,1472, he was sent as Apostolic Legate to Spain to preach the crusade. During his return, on October 10, 1473, his ships laden with his praeda and 30,000 gold coins were struck by a storm, and all was lost; three bishops also died, along with 75 members of his retinue, twelve lawyers, and six knights [Ammannati, Epistolae 534]. He returned to Rome on October 24, 1473 [Eubel II, p. 38, no. 318, no. 330].

- Oliviero Carafa (aged 54) [Neapolitanus], son of Francesco Carafa, grandson of Carlo "Malizio" Carafa, nephew of Diomedes, first Count of Maddaloni (d. 1487); his mother was Maria Origlia, daughter of Giovan Luigi, Signore di Vico Pontano, and Anna Sanseverino. Suburbicarian Bishop of Sabina Previously Cardinal Priest of S. Eusebio (1470-1476), and earlier Cardinal Priest of SS. Marcellino e Pietro (1467-1470). [December 3, 1467 Eubel II, p. 35, no. 276]. Archbishop of Naples (1458-1484). He died on January 20, 1511, at the age of eighty. His family was intensely loyal to the Aragonese dynasty of Naples. In 1472, Sixtus IV placed him in charge of the naval expedition against the Turks [Wadding, Annales Minorum 14, p. 1; A.Guglielmotti, Storia della marina pontificia II (Firenze 1871), pp. 359-391]. "Neapolitanus"

- Marco Barbo (aged 64), Suburbicarian Bishop of Palestrina (died 1491). Previously Cardinal Priest of S. Marco (1467-1478). Patriarch of Aquileia (1465-1491). Bishop of Vicenza (1464-1491). Bishop of Treviso (1455-1470). Legate in Germany, Poland, Bohemia, etc. (1472-1474) [Eubel II, p. 38 no. 314; p. 39 no. 345] "San Marco" "Aquilegiensis" Nephew of Paul II.

- Giovanni Battista Zeno (aged 45), Suburbicarian Bishop of Frascati (died 1501). Cardinal Priest of S. Anastasia (1470-1479). Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Porticu (1468-1470). Bishop of Vicenza (1470-1501). (died 1501) Nephew of Paul II. "S. Maria in Porticu"

- Stefano Nardini (aged ?), Cardinal Priest of S. Maria in Trastevere (1476-1484). Archbishop of Milan (1461-1484). He died on October 22, 1484 [Eubel, Hierarchia catholica II, p. 47 no. 504]

- Giovanni Battista Cibo (aged 52), Cardinal Priest of S. Cecilia (died 1492). Bishop of Molfetta.

- Giovanni Arcimboldi (aged 63), Cardinal Priest of S. Prassede (died 1488). Bishop of Novara. "Novariensis"

- Philibert Hugonet (aged ?), Cardinal Priest of SS. Giovanni e Paolo (died September 11, 1494). Bishop of Macon and of Autun. "Matisconensis"

- Giovanni Michiel (aged 38), Cardinal Priest of S. Marcello (died 1503). Nephew of Paul II. "Sancti Angeli"

- Jorge da Costa, O.Cist. (aged 78), Cardinal Priest of SS. Marcellino e Pietro (died 1508). Archbishop of Lisbon. "Ulixibonensis"

- Girolamo Basso della Rovere (aged 50), Cardinal Priest of S. Crisogono (died 1507). Bishop of Recanati. Nephew of Sixtus IV. "Recanatensis" [Eggs, Supplementum novum Purpurae Doctae (1729), 229-230]

- Gabriele Rangoni OFM Obs. (aged 74), Cardinal Priest of SS. Sergio e Bacco. Bishop of Eger (1475-1486), previously Bishop of Transilvania or Erdely in Hungary (1472-1475). He died on September 27, 1486 [Eubel II, p. 49 no. 522]. "Agriensis"

- Pietro Foscari (aged 67), Cardinal Priest of S. Niccola fra le Immagini (died 1485). Administrator of Padua.

- Giovanni d'Aragona (aged 28), fourth child and third son of Ferrante I, King of Naples (d. 1494), and Isabella (d. 1465), the niece of Giovanni Antonio (Giannantonio) Del Balzo Orsini, Prince of Taranto. Cardinal Priest of S. Lorenzo in Lucina and of S. Sabina in commendam (died 1485). Administrator of Cosenza and of Salerno.

- Domenico della Rovere (aged 42), Cardinal Priest of S. Clemente (died 1501). Bishop of Turin (1482-1501). [Eggs, Supplementum novum Purpurae Doctae (1729) 233-235]

- Giovanni de' Conti (aged 70), Cardinal Priest of SS. Nereo ed Achilleo.(1483-1489). subsequently Cardinal Priest S. Vitale (1489-1493). Archbishop of Conza (1455-1484). He died on October 20, 1493, likely from the plague; within 14 days, fourteen of his household also died. The Pope left Rome on October 26, to avoid contagion [Eubel II, p. 50 no. 550, from the Acta Consistorialia].

- Juan Moles de Margarit (aged 63?), Cardinal Priest of S. Balbina (died November 21, 1484). Bishop of Gerona. "Gerundensis"

- Giovanni Giacomo Schiaffinati, Cardinal Priest of S. Stefano al Monte Celio, Bishop of Parma.

-

Francesco Todeschini-Piccolomini (aged 45) [Senensis], son of Nanni Todeschini, the richest man in Siena, and Laodamia Piccolomini, sister of Pius II; he was adopted by Pius. He had been raised, in fact, by Pius, and had been with him in Germany for years from his childhood; he spoke the German language, and was known to most of the important Germans of the time [Baronius-Theiner 29, sub anno 1471, no. 4, p. 499]. Cardinal Deacon of S. Eustachio. He was Administrator (being below the canonical age), and then Bishop of Siena (1460-1503). Protector of the Camaldolese. He had been Rector of the Marches of Ancona from 1460-1463. He was Vicar of Rome, when Pius went on Crusade in 1464. In December, 1468, he and Cardinal d'Estouteville were assigned by Paul II as his Legates to welcome Frederick III and to accompany the Emperor on his journey through Tuscany to Rome; they arrived on the evening of Christmas eve [Agostino Patrizi, Descriptio adventus Friderici III. Imperatoris, p. 206]. He died, as Pius III, on October 18, 1503. Doctor of Canon Law (Perugia).

On February 18, 1471, he had been created Apostolic Legate to Germany; he departed from Rome on March 18 [Eubel II, p. 37 no. 301 and 302; Baronius-Theiner 29 sub anno 1471, no. 4, p. 499]. On June 26, Paul II acknowledged letters from Todeschini from the Diet at Ratisbon, where he was preaching the Crusade, and he writes again on July 13 [L. Pastor, History 4, pp. 501-503]. He returned to Rome on December 27, 1471 [Eubel II, p. 37, no. 312]. His associate in the German Legation was Johannes Antonius Campani, Bishop of Interamna (1463-1472), who was a friend and correspondent of both Cardinal Bessarion and Cardinal Giacomo Ammannati-Piccolomini, and was also author of the Life of Pius II [J. B. Mencken (ed.), Jo. Antonii Campani Epistolae et Poemata, una cum vita auctoris (Leipzig 1707)].

He was also Protector of the Canons Regular of S. Augustine of the Most Holy Savior by 1485 [Bullarium Canonicorum Regularium Congregationis Sanctissimi Salvatoris (Romae 1733), pp. 102-108, nos. 43-49] . - Raffaele Sansoni Riario (aged 24), Cardinal Deacon of S. Giorgio in Velabro (died 1521). Camerlengo. "S. Georgii" (He is listed among the Cardinal Deacons at the Conclave of 1484 both by Burchard and the Consistorial Archives; cf. Eubel II, 18).

- Giovanni Battista Savelli (aged 62?), Cardinal Deacon of S. Nicola in Carcere (ca.1483-1498), previously Cardinal Deacon of Ss. Vito e Modesto in Macello Martyrum (1480-1483) He was Legate in Perugia at the time of his creation. (died 1498).

- Giovanni Colonna (aged 28), Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Aquiro (died 1508). Administrator of Rieti.

- Giovanni Battista Orsini (aged 34?), Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Domnica (died 1502).

- Ascanio Maria Sforza Visconti (aged 29), Cardinal Deacon of SS. Vito e Modesto in Macello Martyrum. Bishop-elect of Pavia (1479-1505). He was Vice-Chancellor S.R.E. from 1492 to 1505. He died on May 27, 1505 [Eubel II, p. 20 n. 2].

- Ludovicus Joannes Mila (Luis Juan del Milà y Borja) [Valencia, Spain] (aged 54), son of Juan de Mila of Jativa and Catalina de Borja, sister of Calixtus III. Cardinal Priest of SS. Quattro Coronati (died 1510). Bishop of Segovia (1453-1459). "Segobricensis". Sent as Legate to Bologna; he left Rome on January 7, 1457 [Eubel II, p. 34]. He was made Bishop of Lerida (Ilerdensis) on October 7, 1459 [Eubel II, p. 167], a post he held until his death. Sent as Commissioner to compose differences between Barcelona and King John of Aragon In 1464, he was again being sent on a legation to Spain; on April 5, 1464, he left Rome for Florence, from which he intended to proceed to Catalonia [Eubel II, p. 33; Baronius-Theiner 29, sub anno 1464 no. 32]. He took possession of the Diocese of Ilerda on July 20, 1464. He returned to Rome, however, on February 10, 1467 [Eubel II, p. 35, no. 271]. On May 13, 1468, he and several other cardinals had leave the City due to pestis and aeris intemperiem, on the understanding that they return by October 1; Ludovico Mila did not do so, and therefore on October 15, his income from the treasury of the Sacred College was cut off [Eubel II, p. 36, nos. 280 and 286]. He subsequently returned to Spain permanently, and died at Belgida, Spain, in 1510, and was buried in the Dominican convent of Santa Ana in the village of Albaida [Espana Sacrada Tomo 47, 84-87]. "Segobricensis"

-

Thomas Bourchier (aged 67) [England], third son of Guillaume Bourchier, Comte d' Eu; and Anne, daughter of Thomas of Woodstock, sixth son of Edward III. His elder brother Henry was Earl of Essex. His sister Eleanor was married to John Mowbray, third Duke of Norfolk. Cardinal Priest of S. Ciriaco alle Terme Diocleziane (1468-1486) [May 13, 1468: Eubel II, p. 36, no. 281]. He was promoted Cardinal at the request of King Edward IV, whom he had crowned (June 28, 1461). Archbishop of Canterbury (1454-1486) [Brady, Episcopal Succession in England I, p. 3]. Bishop of Ely (1443-1454). Bishop of Worcester (1433-1443). He was consecrated at Blackfriars, London, by Henry Beaufort of Winchester, John Kemp of York, Robert Nevill of Salisbury and John Lowe (Lobbe) of St. Asaph, on May 15, 1435 [Stubbs, Registrum sacrum anglicanum, p. 8]. Chancellor of the University of Oxford (1433-1436) [Le Neve, Fasti ecclesiae Anglicanae III, p. 467; Dictionary of National Biography reissue Vol. 2 (1908), 923; original edition Volume 6 (1886) ]. M.A. Oxon. Doctor in utroque iure He died on March 30, 1486 [Eubel II, p. 48 no. 519; Le Neve, I, p. 23, who quotes his epitaph with the date of his death in n. 4].

- Jean Balue (aged 63?), Suburbicarian Bishop of Albano, previously Cardinal Priest of S. Susanna (1467-1483). Bishop of Angers (1467-1491), and before that Bishop of Evereux (1465-1467). In legibus licentiati, prothonotarii apostolici, de prebenda ecclesiae Carnotensis [Bull of Pius II, May 1, 1462; see Forgeot, xxvii]; his degree was perhaps from Angers, ca. 1457 [Forgeot, p. 4]. From 1483-1485 he was Legate in France. On August 23, 1484, his request to visit his benefices was denied in the name of the King, due to the death of the Pope; on August 24, he requested leave to go to Rome [ A. Bernier (ed.), Procès-Verbaux des séances du Conseil de Régence du Roi Charles VIII (Paris 1836) pp. 75 and 77]. Obviously he was not present at the election, which took place on August 29. From 1485, he was ambassador of Charles VIII in Rome and Protector of France [Eubel II, p. 48 no. 511]. He arrived in Rome on February 8, 1485, and was greeted by 12 cardinals sent by Sixtus IV [Burchard Diarium I, p. 138 ed. Thuasne; p. 67 ed. Gennarelli]. Next day he was received by the Pope and joined Consistory. As ambassador, he continued to press the claims of René of Anjou, Duc de Lorraine, to the throne of Naples. In summer, 1491, he was Legate to the Marches of Ancona. News of his death on Wednesday, October 5, reached the Apostolic Camera on October 7, 1491 [Eubel II, p. 49 no. 537]. "Andegavensis". [G. L' Eggs, Supplementum novum Purpurae Doctae (1729) pp. 223-228].

- Pedro González de Mendoza (aged 56), Cardinal Priest of S. Croce in Gerusalemme (died 1495). Archbishop of Sevilla and Administrator of Sigùenza.

- Charles de Bourbon (aged 49), son of Charles, Duc de Bourbon et Auvergne; and Agnes of Burgundy; brother of dukes John and Peter. Cardinal Priest of S. Martino ai Monti (died 1488). Administrator of Clermont, administrator (at the age of 11) and then Archbishop of Lyon (1446-1488). He first visited his diocese as Archbishop in 1485, along with his sister the Princess d'Orange [J.-B. Monfalcon, Histoire de la ville de Lyon I (Lyon-Paris 1847) , p. 542]. He died on September 17, 1488. [Gallia christiana 4 (Paris 1728), 177-179]. On Monday, August 23, 1484, he attended the Regency Council of Charles VIII, and again on August 28 and September 6 [ A. Bernier (ed.), Procès-Verbaux des séances du Conseil de Régence du Roi Charles VIII (Paris 1836) pp. 75—at which note is taken for the first time of the passing of the Pope; p. 86 and 88 and 96]. Clearly he was not in Rome for the election on August 29.

- Pierre de Foix (aged 35), Cardinal Deacon of SS. Cosma e Damiano (died 1490). Administrator of Bayonne, Bishop of Vannes (1476-1490). On August 16 and 17, 1484, he attended the Regency Council of Charles VIII, and again on September 6 [ A. Bernier (ed.), Procès-Verbaux des séances du Conseil de Régence du Roi Charles VIII (Paris 1836) pp. 54-58; 88 and 96]. He did not go to Rome.

- Paolo Fregoso (aged 56) [Genoa], son of Doge Battista I (1437) and brother of Doge Pietro II (1450), Cardinal Priest of S. Anastasia. Archbishop of Genoa (1453-1498). He was Doge of Genoa, in 1462, 1464, and 1480. Bishop of Ajaccio in commendam [Eubel II, p. 79]. He died in Rome on March 22, 1498 [Eubel II, p. 53 no. 600]. His family were hostile to the Aragonese, Charles VIII, and the Dukes of Milan.

The Conclave

On the 26th of August, after Mass, celebrated by the Cardinal of S. Marco, Cardinal Barbo, the Cardinals met and began discussions; their main concern was the preparation of the Electoral Capitulations, to be signed by all cardinals, granting extraordinary privileges to the cardinals and circumscribing the powers of the papacy (Burchard, p. 16G) On the next day the cardinals continued their discussions, and finally produced two documents, one for the cardinals themselves to agree to, and one for the new pope to sign, which Burchard quotes in their entirety (Burchard, pp. 17-28G). Had they been carried out, the Church would have been ruled by a self-perpetuating, aristocratic, board of directors, with the Pope as a tightly circumscribed chairman (or so the somewhat hysterical papal viewpoint would have it).

On Saturday the 28th , after several cardinals celebrated mass, the Cardinals and the other conclavisti signed the electoral capitulations which had been prepared (Burchard, 17-28G). Cardinal Piccolomini, was the scrutator. Voting began with the Cardinal Vice-Chancellor Borgia, followed by the Cardinal of Naples, Cardinal Carafa (Burchard, p. 29G) When the votes were counted no cardinal had more than ten votes, seventeen being needed to elect. Cardinal Barbo received ten votes. Then in the afternoon, the matter of Cardinal Sforza was raised; he had been named a cardinal at the end of Sixtus IV's life, but the ceremonies of the opening and closing his mouth had not been completed. The issue was whether he was entitled to vote, and the cardinals decided in the affirmative (Burchard, p. 30G):

Fuit his diebus a nonnulis dubitatum, an R.D. Cardinalis Ascanius qui post obitum fel. rec, Sixti Papae quarti, Cardinalis ad Urbem venit, et cui postmodum os apertum non erat, in electionem futuri Pontificis votum dare deberet, cum non esset illa ceremonia de oris aperitione, quae in novis cardinalibus observatur, in eo consumata. Tandem fuit per RR. DD. cardinales conclusum, quod cum non sit praefato Cardinali Ascanio os clausum, possit liber electioni interesse, et in ea votum dare, et ea observata fuisse in aliis. Si autem praefato Ascanio Cardinali per fel. rec. Sixtum papam quartum os clausum fuisset, et tempore clausurae antequam idem Sixtus eidem os aperuisset, ipse Sixtus diem extremam clausisset, quod tunc, propter oris huiusmodi clausuram, non potuisset praefatus Cardinalis Ascanius in electione praedicta votum dare.

A rumor went about on the evening of the 28th (Saturday) that Cardinal Barbo, the Cardinal of St. Mark, had been elected pope, but the rumor was disproved when the evening meals of the cardinals were delivered (Pontano, 42).

The Election

Infessura (pp. 170-171) claims to have the inside information of how the election of the new pope came about. On Saturday evening (he says) Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere said to Cardinal Barbo, who at that time had eleven votes, that, if he would promise his house to Cardinal d' Aragona (son of King Ferdinand), that he would get him three more votes to make fourteen; but Barbo replied that he certainly would not do it, for, if he did do it, the election would not be canonical. Likewise, his house was better fortified than the Castel S. Angelo, and if he did that, it would perhaps be a cause of disturbance to the city and all Christendom, because the King (Ferdinand) could easily come there and make himself master of the City and disturb the order of the Church. Then he went to Cardinal Borgia, the Vice-Chancellor, and asked him if he wanted to make a pope in accordance with their votes. And he consented, so long as he could frustrate the election of Barbo, whom he hated. Then, overnight as the cardinals were sleeping in their cells, della Rovere and Borgia spoke with each of the cardinals (except de' Conti, Barbo, Carafa, da Costa, Piccolomini, de Margarit, and some say Zeno) telling them that if they gave their votes to Cibò, they would receive many benefits. In the morning those who had been sleeping were summoned and told that they had make a pope. "Who?" they asked. "The Bishop of Molfetta," they replied. "How?" "Last night, while you were sleeping, we all agreed." The seven, seeing that there were already eighteen or nineteen votes for Cibò, they went along. It was only the next day that it was discovered all the promises that Cibò had made to get elected. (Infessura provides a list of the simoniacal grants):

Cardinal Savelli: possession of the fortress called Monticelli on part of the Island

Cardinal Colonna: the fortress of Ceprano, the Legateship of the Patrimony, 25,000 ducats for

restoration of his burned out palace and contents, and the first available benefice worth a

minimum of 7,000 ducats.

Cardinal Orsini: the Legateship of the Marches and the castle at Cerveteri

Cardinal Ugonetti: the castle at Capranica and the Bishopric of Avignon

Cardinal d' Aragona: Pontecorvo, and the new pope's old palace at S. Lorenzo in Lucina

Cardinal Schiaffinati: the palace of S. Giovanni della Magliana and all of its outbuildings

Cardinal Nardini: the office of Archpriest of the Lateran Basilica, and the Legateship of Avignon

Cardinal della Rovere: the town of Fano, and five other neighboring properties; and the promise

to make his brother Captain General of the Church

On Sunday, August 29, after private masses and a Mass of the Holy Spirit by the Sacristan, voting began again. It was known that Cardinal Cibò (also called Cardinal Molfetta) would be elected because his conclavists, unlike the rest, did not repair to the chapel, but went to the Cardinal's cell to take care of their property. When the vote was taken (Burchard says he knows nothing about an accessio) Cardinal Giovanni Battista Cibò was elected unanimously; he was fifty-two years old.

Cardinal Cibò was crowned as Innocent VIII on September 12 (Burchard, 75-83 T), and took possession of the Lateran Basilica on the same day (Burchard, 83-90 T).

Gaspare Pontano, Il diario romano di Gaspare Pontano (a cura di Diomede Toni) (Citta di Castello 1908) [Rerum Italicarum Scriptores, Raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento, Tomo III, Parte II, fascicolo 67] pp. 37-42.

Notarius de Antiportu (Naniporto), Diarium Romanum Urbis [Muratori, Rerum Italicarum Scriptores, Raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento, Tomo III, Parte II, fascicolo 67, 1069-1109]

"Historia interpontificii, ab anonymo coaevo Latine descripta," in Daniel Papebroch, Conatus chronico-historicus (Antverpiae: apud Michaelum Knobbarum 1685), 137-139.

Achille Gennarelli (editor), Johannis Burchardi Argentinensis ... Diarium ... (Firenze 1854), 3-33. L. Thuasne (editor), Johannis Burchardi Argentinensis . . . Diarium sive Rerum Urbanum commentarii Volume I (Paris 1883) pp. 9-62. Stefano Infessura, Diario della citta di Roma (a cura di Oreste Tommasini) (Roma 1890) 155- . Gaetano Moroni Dizionario di erudizione storico-ecclesiastica 36 (Venezia 1846) 6. Ludwig Pastor, The History of the Popes (edited R. K. Kerr) second edition Volume 5 (London: Kegan Paul 1902) 227-248. Ferdinand Gregorovius, The History of Rome in the Middle Ages (translated from the fourth German edition by A. Hamilton) Volume 7 part 1 [Book XIII, Chapter 4] (London 1900) 283-290. J.-P. Christophe, Histoire de la papauté pendent le XVe siècle (Paris 1863) Volume II, pp. 285-305; 586-587 (letter of Pier Filippo Pandolfini to Lorenzo de' Medici). G. Bourgin, "Les cardinaux français et le diaire caméral de 1439-1486," Mélanges d' archéologie et d' histoire 24 (1904) 277-318.

Joannes Baptista Gattico, Acta Selecta Caeremonialia Sanctae Romanae Ecclesiae ex variis mss. codicibus et diariis saeculi xv. xvi. xvii. Tomus I (Romae 1753)

On Cardinal Riario: Angelo Poliziano, "La congiura de' Pazzi," Prose volgari inedite et poesie latine e greche edite e inedite (edited by Isidoro del Lungo) (Firenze 1867), p. 94. Niccolò Machiavelli, History of Florence Book VIII, chapter 1. G. Moroni, Dizionario di erudizione storico-ecclesiastica 57 (Venezia 1852). Charles Berton, Dictionnaire des cardinaux (1857) p. 1445. Erich Frantz, Sixtus IV und die Republik Florenz (Regensburg 1880) 197-230, especially 207 (highly favorable to Sixtus and the Riarios).

On Cardinal Balue: Henri Forgeot, Jean Balue, Cardinal d' Angers (1421?—1491) (Paris 1895).