SEDE VACANTE

July 29, 1644—September 15, 1644

ANTONIO CARDINAL BARBERINI, iuniore (1607-1671), was the son of Carlo Barberini and Costanza Magalotti, and nephew of Pope Urban VIII (Maffeo Barberini, 1623-1644), of the Capuchin Antonio Card. Barberini, seniore, (1624), and of Lorenzo Card. Magalott (1624-1637)i. His brother Francesco became Cardinal on the election of their uncle to the papacy, and his brother Taddeo became Prince of Palestrina and Prefect of Rome. He was the cousin of Francesco Maria Card. Machiavelli (who became cardinal in 1641), and uncle of Carlo Card. Barberini (1653). He was Grand Prior in Rome of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem.

The accession of his uncle brought Antonio Barberini and his brothers many positions of power, wealth and influence. He became Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Aquiro in 1627, and Camerlengo of the Holy Roman Church on July 28, 1638, a position which he held until his death on August 3, 1671. In that capacity he presided over the Conclaves of 1644, 1655, 1667 and 1669-1670. He was Abbot Commendatory of the Abbey of Nonantola (1632-1671). The authoritarianism, arrogance and greed of the family ("Quod non fecerunt Barbari, fecerunt Barberini.") brought a strong reaction on the death of Urban VIII in 1644. In 1645 Antonio and Taddeo fled to Paris (where Urban VIII had once been ambassador), and remained in exile at the Court of Louis XIV (under the patronage of Cardinal Giulio Mazzarini) until 1653; Antonio Barberini became Grand Almoner of France and a member of the Order of the Holy Spirit. In 1657 he was nominated Archbishop of Rheims, a choice which was approved by Pope Alexander VII. He became Cardinal Bishop of Palestrina in 1661. He died in Rome on August 3, 1671.

The position of Marshal of the Holy Roman Church and Custodian of the Conclave was usurped from Prince Bernardino Savelli (whose family had held the distinction since the thirteenth century) by Don Taddeo Barberini [Moroni, Dizionario di erudizione storico-ecclesiastica 42 (Venezia 1847), 283-284; Siri, p. 592].

The Secretary of the Sacred College of Cardinals was Giuseppe Frenfanelli, canon of the Vatican Basilica.

The Confessor of the Conclave was Father Valentino Magnonius (Magnoni), SJ. [Bullarium Romanum 15 (Augustae Taurinorum 1868), p. 358].

The Ceremoniarii were: Gaspar Servantius, Dominicus Bellus, Francesco Maria Phebaeus, and Carolo Vicenzio Cavaratius. [Bullarium Romanum (Turin edition) Volume 15, p. 355]

Background

Due to the struggle over the succession to the Duchy of Mantua, Urban VIII managed to turn Spain into his enemy (see, e.g, Gregorovius, Urbano VIII e la sua opposizione alla Spagna e all' Imperatore). His continual preoccupation with the possibility that the Empire, led by Ferdinand II (1619-1637), would come to dominate the Italian states, along with support from the Hapsburg King of Spain, Philip IV, who was also King of Naples, which he ruled through a Viceroy. Being surrounded by the Hapsburgs was as big a fear for Urban as it was for Cardinal Richelieu. This had caused Urban to reverse the pro-Imperial policy of Paul V for a pro-French policy, much as he disliked many of the policies of Richelieu.

Europe had been wracked for decades by the series of military engagements that are called the Thirty Years War (1618-1648). There was a religious component, a struggle between Protestant and Catholic Powers. There were nationalistic components. France in particular was centralizing and consolidating political power, to the disadvantage of the nobility. With the nobility's help, Louis XIII's mother and brother were constantly conspiring with the nobility and with Spain to frustrate Cardinal Richelieu's plans. Spain was engaged in an attempt to overthrow the French government, which, ever since the Wars of Religion, had granted recognition and (in some sense) autonomy to protestants in France. This accommodation was anathema to the orthodoxy of the Spanish monarchy, and with the administration of Cardinal Richelieu supporting the Protestant Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden, the Spanish believed that it was necessary to destroy France. They were further convinced, since France was seeking to rationalize its eastern borders, which put pressure on the Spanish Netherlands and on the Imperial vassals between the Rhine and Paris. War between Spain and France ensued (1635-1659). King Philip's marriage to Mariana of Austria, the daughter of Emperor Ferdinand, brought Spain closer to Vienna, and into stronger conflict with Richelieu and Gustavus Adolphus. The Empire, with Prince Wallenstein as its war leader, was eager to recover territories in central and northern Europe which had been lost to Protestant princes, and which were now being united against the Catholic Empire (and conquered) by Gustavus Adolphus; his death in 1632 only somewhat diminished the threat to the Catholic powers. The Spanish participated in the campaign that led to the Battle of Nördlingen in 1634, improving, as they believed, their security in the possession of the Spanish Netherlands. Prince Wallenstein, however, had also been interested in creating an independent principality for himself in Bohemia (Friedland), which was contrary to the wishes of his employer, the Emperor, and threatening to a number of German states and to Poland. His assassination on orders of, or with the consent of, the Emperor shocked Christian Europe (February 25, 1634).

In this confusion, Pope Urban VIII (Barberini) supported the French, though he was strongly—but ineffectually—critical of Richelieu's involvement with the Protestants. Ever since his own War of Castro (1641-1644) had caused Odoardo Farnese, Duke of Parma, to seek support against the Pope through an alliance with France, Modena, Tuscany, and Venice, Urban was isolated and defeated in his hopes and ambitions. Richelieu had sent Hughes de Lionne to Italy in 1642 to attempt to patch up a peace between the League and the Pope—a commission extended by Mazarin after Richelieu's death on December 4—but Lionne was unsuccessful and returned to France in September, 1643 [A. Chéruel, Histoire de France pendant la minorité de Louis XIV Tome I (Paris 1879), 230-233]. Urban's troops, led by his nephews, Taddeo, Prince of Palestrina, and Fra Antonio Barberini, the Younger, ended in disaster at the Battle of Lagoscuro in 1644. It was Cardinal Bichi who finally negotiated the Peace of Ferrara on March 31, 1644.

Death of Urban VIII (Barberini)

Europe had been disturbed by a number of significant deaths in a very short time. Cornelius Jansen had died on May 6, 1638. Cardinal Richelieu, First Minister of the King of France died on December 4, 1642. His master, King Louis XIII died less than six months later, on May 23, 1743, leaving France in the keeping of a Regency headed by Anne of Austria and Cardinal Jules Mazarin. Also, an internal political crisis in Spain (the revolt of Catalonia, 1640-1652, aided by the French) in 1643 brought the dismissal from power of the Count-Duke of Olvares; Philip IV announced that he would rule neither through a junta nor through a favorite, but would rule personally himself. Pope Urban VIII died on July 29, 1644. An avviso from Rome, dated August 8, 1644, had the following statement [V. Forcella, Catalogo dei manoscritti relativi alla storia di Roma III (Roma 1881), p. 326, Codex Ottobonianus Latinus no. 3348]:

Quando il Pontefice hebbe reso lo spirito come fu scritto et che fu aperto il suo corpo, et poi inbalsamato, et collocato nella Cappella di Sisto si disse che li medici, et chirurgi havevano osservato nella diofragma dove si contiene il cuore un osso in forma di meza luna con alcune pietre nella vessica del fiele....

On his death, the people of Rome rose in a fury against the Barberini. Urban had been an outrageous nepotist, who did nothing to restrain the arrogance and cupidity of his nephews, Francesco, Antonio, and Tad(d)eo.

The Cardinals

The official list of Conclavists with the names of each of their Cardinals is contained in the usual bull on the privileges and absolutions granted to the Conclavists: Bullarium Romanum 15 (Augustae Taurinorum 1868), pp. 355-358 (January 31, 1645) [Coquelines VI.iii (1760), pp. 17-19]. A helpful list of forty Cardinals and their assigned titles is contained in the Constitution of Innocent X, Militantis Ecclesiae Regimini, on the titles and insignia of Cardinals [Bullarium Romanum (Augustae Taurinorum 1868), 341-342 (December 19, 1644)]. Patritius Gauchat, Hierarchia Catholica IV (Monasterii 1935), p. 27 n. 2. Forty of the cardinals were creature of the Barberini [Wahrmund, "Beiträge...", p. 5]. Ciaconius-Olduin IV, 643-644. Six cardinals were creature of Paul V. Thirty-nine cardinals were creature of Urban VIII. There were eight vacancies in the Sacred College [Siri, p. 630].

It was Urban VIII who decreed that cardinals were to be called "Eminentissimus and Reverendissimus".

- Marcello Lante della Rovere (aged 83), Bishop of Ostia–Velletri (1641–1652), Dean of the Sacred College of Cardinals. Bishop of Todi (1606-1625) In 1650, under the authority of Pope Innocent X, he opened and closed the Holy Door at S. Paolo fuore le mura, for the Jubilee of 1650 [V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma XII, p. 17, no. 27]. (died 1652)

- Pier Paolo Crescenzi (aged 72) [Romanus], Bishop of Porto e Santa Rufina (1641–1645). Previously Cardinal Priest of SS. Nereo ed Achilleo (1611-1629). Former Bishop of Orvieto (1621–May, 1644). (died February 19, 1645; buried in S. Maria in Vallicella [V. Forcella Inscrizione delle chiese di Roma 4, p. 159, no. 382])

- Francesco Cennini de' Salamandri (aged 77), Bishop of Sabina (1641–1645), called the Cardinal of S. Marcello. Nuncio to Spain (1618–1621). (died October 2, 1645)

- Guido Bentivoglio d' Aragona (aged 64), Bishop of Palestrina (1641–1644). Nuncio to France (1616–1621). [He was still in Conclave on August 29, but he left the Conclave, and died at his house during the Conclave, on September 7, 1644] (His conclavists are listed in the List of Conclavists).

- Giulio Roma (aged 59), Bishop of Tusculum (Frascati) (1644–1645), and of Tivoli (1634–1652). (died 1652) He voted for Pamphili, outraged by the exclusiva against Sacchetti [Siri, p. 620].

- Luigi Capponi (aged 62) [Florence], Cardinal Priest in the title of S. Lorenzo in Lucina (1629–1659). Archbishop of Ravenna (1621–1645). (died 1659) A supporter of the French.

- Alfonso de la Cueva-Benavides y Mendoza-Carrillo (aged 72) [Spain], Cardinal Priest in the title of S. Balbina. Ambassador of the King of Spain in the Spanish Netherlands. [became Bishop of Palestrina on October 17, 1644] (died 1655) Member of the Spanish faction.

- Antonio Barberini, OFM.Cap. (aged 75), Cardinal Priest in the title of S. Maria Transtiberim (1642-1646). Formerly of S. Pietro in Vincoli, and of S. Onuphrio (1624–1637), and sometimes called "S. Honuphrii" [Bullarium Romanum 15, 356]. Librarian of the Holy Roman Church (1633–1646). Major Penitentiary (1633–1646). (died 1646). Brother of Urban VIII. He was excluded by the Grand Duke of Tuscany, and rejected by the Spanish [Siri, p. 598]. One of his Conclavists was Annibale Albani, Custodian of the Vatican Library [His tomb inscription in: Città e famiglie nobili e celebri (n.d.: Storia di Roma, Titolo X), p. 11; he died in 1650 at the age of 45]. His Majordomo, Vincenzo Martinozzi, was married to the sister of Cardinal Mazarin. Mazarin's niece, Laura Martinozzi, married Alphonse d'Este, son of the Duke of Modena.

- Ernest Adalbert von Harrach (aged 45), Cardinal Priest in the title of S. Prassede. Archbishop of Prague (1623–1667). (died 1667)

- Bernardino Spada (aged 50), Cardinal Priest in the title of S. Pietro in Vincoli (1642–1646). Nuncio in France (1623–1627). (died 1661)

- Federico Baldissera Bartolomeo Cornaro [Cornelius] (aged 64) [Venice], Son of Doge Giovanni Cornaro, Cardinal Priest in the title of S. Marco (1629–1646). Patriarch of Venice (1631–1644). (died at the age of 68 1653) An inscription of his in S. Maria della Vittoria [V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma IX, p. 64 no. 120].

- Giulio Cesare Sacchetti (aged 58) [Florence, but born in Rome], Cardinal Priest in the title of S. Susanna (1626–1652). Doctorate in law (Pisa). Formerly Vice-Legate of Bologna. Referendarius of the Tribunal of the Signature of Justice. Bishop of Gravina (1623–1626)—which, according to Bargrave (p. 24), he never visited. Nuncio in Spain (1624–1626). Bishop of Fano (1626–1635). Legate in Ferrara (1627-1630) Legate in Bologna (1637-1640) (died June 28, 1663). [Cardella VI, 261-263]. His candidacy for the Papacy was opposed by the Grand Duke of Tuscany [Siri, p. 629-630].

- Giovanni Domenico Spinola (aged 64) [Genoa], grandson of Giovanni Battista Lercari, Doge of Genoa. Cardinal Priest in the title of S. Caecilia (1629–1646). Bishop of Mazara (1636–1646) [Roccho Pirro, Sicilia Sacra II 3rd. ed. (Palermo 1733), pp. 841-842; 860-861]. (died 1646)

- Giovanni Battista Pamphili (aged 70) [Romanus], son of Camillo Pamphilj and Flaminia Cancellieri del Bufalo. Nephew of Cardinal Girolamo Pamphili and descendant of Alexander VI. Cardinal Priest in the titulus of S. Eusebio (1630-1644). Vice-Legate in Ferrara (1623-1624). Nuncio in Naples (1621-1625). Nuncio to Philip IV of Spain (1626-1629). Prefect of the SC of the Council (1639-1644). (died 1655, as Pope Innocent X)

- Gil Carrillo de Albornoz [Aegidius Alternotius] (aged 55) [Talavera, Archdiocese of Toledo, Spain], grand-nephew of Cardinal Diego Espinosa y Arevalo (1568-1572), President of the Council of Philip II. Cardinal Priest in the title of S. Pietro in Montorio. (died 1649) Former Archbishop of Taranto.

- Alphonse-Louis Duplessis de Richelieu, O.Carth.(aged 62) [Poitou/Paris], Cardinal Priest in the titulus of Sma. Trinità al Monte Pincio (1635–1653). Archbishop of Lyon (1628–1653). Grand Almoner of France, in succession to Cardinal Rochefoucauld (May 4, 1632). (died 1653). Brother of Cardinal Armand de Richelieu, First Minister of Louis XIII ( who died on December 4, 1642).

- Ciriaco Rocci (aged 63) [Roman], Cardinal Priest in the title of S. Ciriaco e Salvatore in Lauro (1635–1651). Former Nuncio in Switzerland (1628-1630) and Austria (1630-1633). (died 1651)

- Giovanni Battista Pallotta (aged 50) [Caldarola, Diocese of Camerino, Picenum], Cardinal Priest in the title of S. Silvestri in Capite (1631–1652). Nephew of Cardinal Giovanni Evangelista Palotta. Apostolic Collector in Portugal (to 1628) [His instructions: Laemmer, Zur Kirchengeschichte, p. 28 no. IX]. Governor of Rome (1628). Nuncio in Vienna (1628–1630), to deal with the issue of the succession to the Duchy of Mantua and Monferrat [Nuntiaturberichte aus Deutschland 1628-1635, Nuntiatur des Pallotto 1628-1630 (Berlin 1895), xxxvi-cvi]. Legate in Ferrara (1631-1634). (died January 22, 1668)

- Cesare Monti (aged 51) [Milan], Cardinal Priest in the title of S. Maria Transpontina. Archbishop of Milan.(died 1650)

- Francesco Maria Brancaccio (aged 52) [Naples], Cardinal Priest in the title of the Basilica XX Apostolorum (1634–1663). Doctor of Theology (Naples, 1620). Formerly Bishop of Capaccio in the Kingdom of Naples (1627–1635). When a servant of his killed a soldier, he was cited to the court of the Viceroy of Naples, but not wanting to acknowledge civil jurisdiction, he fled to Rome. Despite demands for his readmission to his diocese, the Viceroy refused and demanded his replacement. Instead the Pope made him a cardinal, and in 1638 made him Bishop of Viterbo and Toscanella (1638–1670). His career culminated in his being named Cardinal Bishop of Porto e Santa Rufina (1671–1675) (died 1675)

- Alessandro Bichi (aged 48) [Siena], Cardinal Priest in the titulus of S. Sabina. Bishop of Carpentras. (died 1657). Close advisor of Cardinal Mazarin. Chief French agent inside the Conclave, along with Cardinal Richelieu.

- Ulderico [Rodericus] Carpegna (aged 49), brother of the Conte di Carpegna. Cardinal Priest in the title of S. Anastasia (1634–1659). (died 1679) A friend of the Medici.

- Marco Antonio Franciotti (aged 52), Cardinal Priest in the title of S. Maria de Pace (1639–1666). Bishop of Lucca (1637–1645). (died 1666)

- Stefano Durazzo (aged 50) [Genoa], Cardinal Priest in the title of S. Lorenzo in Panisperna. Archbishop of Genoa (1635–1664), Legate in Ferrara. (died 1667)

- Francesco Macchiavelli (aged 36) [Florence], Cardinal Priest in the title of SS. Giovanni e Paolo (1642–1653). Bishop of Ferrara (1638–1653). (died 1653) A cousin of the Barberini.

- Ascanio Filomarino (aged 61) [Naples, from Chianchisella in the Diocese of Benevento], Cardinal Priest in the title of S. Maria in Ara Coeli (1642–1666). Archbishop of Naples (1641–1666). He started his career as chamberlain to Cardinal Maffeo Barberini, with whom he shared an interest in astrology. (died 1666)

- Marco Antonio Bragadin (aged 53) [Venice], Cardinal Priest in the title of SS. Nereo ed Achilleo (1642–1646). Bishop of Vicenza (1639–1655). (died 1658)

- Pier Donato Cesi (aged 61) [Roman], of the Dukes of Acquasparta. Cardinal Priest in the titulus of S. Marcello (1642–1656). Doctor of law. Protonotary Apostolic by appointment of Paul V. Made a Cleric of the Chamber by Urban VIII, and appointed Prefect of Civitavecchia (1625). Appointed Treasurer in 1634. Legatus a latere in Perugia. Nominated by King Philip IV to be a Canon of the Cathedral of Toledo, with the consent of Urban VIII. (died 1656)

- Girolamo Verospi (aged 45) [Roman], nephew of Cardinal Fabrizio Verospi (1627-1639). Cardinal Priest in the titulus of S. Agnese in Agone (1642–1652). Auditor of the Rota. Bishop of Osimo (1642–1652). (died 1652) A parente of the Barberini.

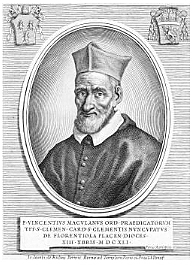

- Vincenzo Maculano, OP (aged 65) [Fiorenzola, Diocese of Piacenza, Duchy of Tuscany], Cardinal Priest in the titulus of S. Clemente (1642–1667). He was the son of a mason. He took the habit at the Convent of the Dominicans at Pavia; his baptismal name had been Gasparo. He was educated at the Dominican Convent in Bologna, and became Inquisitor for Pavia and then for Genoa (November, 1627–December, 1629) [Siri, p. 645; Catalano De magistro sacrii palatii apostolici (Roma 1751) 161]. In 1629 he was named Procurator General of the Dominicans at the Roman Curia, and when the Minister General, Fra Nicolas Rodolphe, set out on his visit to France, he left Maculano in charge as Vicar General [A. Touron, Histoire des hommes illustres de l' Ordre de S. Dominique V (Paris 1749), 296-313; 449-458; at p. 450].

Maculano was named Comissary of the Holy Office by Urban VIII (Barberini) in 1632, a post he held until 1649. In that capacity he presided over the examinations of Galileo in 1633, which were held in Maculano's chambers in the Palace of the Inquisition [Karl von Gebler, Galileo and the Roman Curia (London 1879), 201]; the duties were shared with Fr. Carlo Sinceri, Fiscal Procurator of the Holy Office [Domenico Berti, Il processo originale di Galileo (Roma 1876), p. 82]. Maculano personally delivered the report on the First Examination (April 12, 1633), which he discussed with Pope Urban and some cardinals on April 27 [Gebler, 213 (letter of Maculano to Cardinal Francesco Barberini, April 28, 1633)]. The second examination was on April 30, and the third on May 10—at which Maculano again presided [Berti, 94]. It was also Fra Vincenzo who, on April 30, 1633, on orders of Urban VIII, granted permission to Galileo to reside in the Tuscan Embassy rather than in accommodations of the Inquisition [Berti, 93]. On June 16, Pope Urban met with the cardinals of the Inquisition and demanded that Galileo be interrogated on "intent"—which could involve torture [Berti, 118]. On June 21, Galileo was interrogated on intent by Fr. Maculano [Berti, 119]. On June 22, he appeared before the Cardinal Inquisitors at the Minerva, and was condemned; the Cardinals who were present were:Gasparo Borgia, S.Croce in Gerusalemmethree of the Cardinals, however, did not sign the condemnation: Francesco Barberino, Borgia, and Zacchia. [Gebler, 348-351; Berti, 149; S. Pagano (editor), I documenti del Processo di Galileo Galilei (Vatican 1984)]. On July 2, 1633, it was Fra Vincenzo who personally notified Galileo, in the name of Pope Urban VIII, that he could leave Rome, travel to Siena, and turn himself over to the Archbishop of Siena, to be placed under house arrest [Antonio Favaro, Galileo e l' Inquisizione (Firenze 1907), 103; Gebler, 248].

Fra Felice Centino, O.Min.Conv., S. Anastasia

Guido Bentivoglio, S. Maria del Popolo

Desiderio Scaglio, S. Carlo

Fra Antonio Barberino, O. Min. Cap., S. Onofrio

Laudivio Zacchia, S. Pietro in vincoli

Berlinguero Gessi, S. Agostino

Fabrizio Verospi, S. Lorenzo in Panisperna

Francesco Barberino, S. Lorenzo in Damaso

Marzio Ginetti, S. Maria Nuova

In 1638, Urban sent Maculano to Malta, where he gave demonstration of his scientific skills by designing improvements in several fortresses. He presented his plans to the Grand Master of the Knights of Malta on September 28, 1638 [W. Porter, A History of the Fortress of Malta (Malta 1858), p. 144, 148; the impression is given that he was engaged in surveying, not constructing]. This was, of course, before he was named Maestro dei sacri palazzi and before he became cardinal. He also performed some restoration work on the Castel S. Angelo [medals of Urban VIII, dated 1628, 1631, show the Castel S. Angelo with the inscription INSTRVCTA•MVNITA•PERFECTA: Bonnani, pp. 583-584; Mazio 191; Spink 977, 999; Nibby, Mura di Roma p. 338; Parker, Archaeology of Rome I, p. 150 (the Porta Portuensis is dated 1640)] and the walls of the City [medals dated An. XX (1643), with the inscription ADDITIS•VRBI•PROPVGNACVULIS: Bonnani, p. 585, no. 22; Spink 1064; Nibby, p. 375 (under Innocent X, 1645)]. The date of Maculano's activity in 1643-1644 under Urban VIII can be gathered from records of the Apostolic Camera and from the diary of Giacinto Gigli [C. Quarenghi, Le Mura de Roma (Roma 1880), 179-187]:

A 2 genn. 1643 riscossa per forza da Chierici di Camera. Nel giugno 1644 fu dato ordine e principio a fortificare la città di Roma, con restringere il circuito delle mura et farlo di forma molto minore di quella che è stata fino ad hora; et si cominciò dalla piazza del Testaccio a tagliare giù le Vigne, le Case, le Chiese, tra le quali deve andare a terra quella di S. Prisca et una parte del Giardino de Matthei, et molthe deliziose ville de diversi signori; et perchè la Basilica di S. Gio. Laterano era per restare fuori delle mura, finalmente fu risoluto che da quella parte si mutasse il disegno, quasi per due miglia; sicchè quella Basilica non rimanesse abbandonata in mano di nemici. Era di tutto questo Architettore il Cardinale Vincenzio Maculani di Firenzuola.. John Bargrave, nephew of the Protestant Dean of Canterbury [Pope Alexander VII and the College of Cardinals, 42-44, written in 1662 while Maculano was still alive], has a long anecdote from an Italian manuscript reporting that Maculano was tearing apart aristocratic property, in particular that of the Mattei, in order to build walls—Bargrave places his work during the War of Castro, 1640-1644.

Urban sent Maculano to Malta, where he gave demonstration of his scientific skills by designing improvements in several fortresses. He presented his plans to the Grand Master of the Knights of Malta on September 28, 1638 [W. Porter, A History of the Fortress of Malta (Malta 1858), p. 144, 148; the impression is given that he was engaged in surveying, not constructing]. This was, of course, before he was named Maestro dei sacri palazzi and before he became cardinal. He also performed some restoration work on the Castel S. Angelo [medals of Urban VIII, dated 1628, 1631, show the Castel S. Angelo with the inscription INSTRVCTA•MVNITA•PERFECTA: Bonnani, pp. 583-584; Mazio 191; Spink 977, 999; Nibby, Mura di Roma p. 338; Parker, Archaeology of Rome I, p. 150 (the Porta Portuensis is dated 1640)] and the walls of the City [medals dated An. XX (1643), with the inscription ADDITIS•VRBI•PROPVGNACVULIS: Bonnani, p. 585, no. 22; Spink 1064; Nibby, p. 375 (under Innocent X, 1645)]. The date of Maculano's activity in 1643-1644 under Urban VIII can be gathered from records of the Apostolic Camera and from the diary of Giacinto Gigli [C. Quarenghi, Le Mura de Roma (Roma 1880), 179-187]:

A 2 genn. 1643 riscossa per forza da Chierici di Camera. Nel giugno 1644 fu dato ordine e principio a fortificare la città di Roma, con restringere il circuito delle mura et farlo di forma molto minore di quella che è stata fino ad hora; et si cominciò dalla piazza del Testaccio a tagliare giù le Vigne, le Case, le Chiese, tra le quali deve andare a terra quella di S. Prisca et una parte del Giardino de Matthei, et molthe deliziose ville de diversi signori; et perchè la Basilica di S. Gio. Laterano era per restare fuori delle mura, finalmente fu risoluto che da quella parte si mutasse il disegno, quasi per due miglia; sicchè quella Basilica non rimanesse abbandonata in mano di nemici. Era di tutto questo Architettore il Cardinale Vincenzio Maculani di Firenzuola.. John Bargrave, nephew of the Protestant Dean of Canterbury [Pope Alexander VII and the College of Cardinals, 42-44, written in 1662 while Maculano was still alive], has a long anecdote from an Italian manuscript reporting that Maculano was tearing apart aristocratic property, in particular that of the Mattei, in order to build walls—Bargrave places his work during the War of Castro, 1640-1644.

In 1639, Pope Urban promoted Maculano to the post of Maestro dei sacri palazzi (1639-1641), in sucession to Fr. Nicolas Riccardi (1629-1639) (who had also been involved in the Galileo case, as the person who licensed the printing of the Dialogue). Riccardi's cousin, Catarina Riccardi Niccolini, was wife of the Tuscan Ambassador in Rome, Francesco Niccolini [Catalano, De magistro sacrii palatii apostolici (Roma 1751), 158-163]. The post of Master of the Sacred Palaces invested Maculano with the authority to issue the imprimatur necessary to publish any book in Rome. On December 16, 1641, Maculano was created Cardinal. He was briefly Archbishop of Benevento (1642-1643), consecrated in Rome on January 19, 1642, by Cardinal Antonio Barberini, OFM Cap. [Gauchat, 113, n. 5]. After eighteen months he resigned the See. Bargrave states [p. 43, quoting an Italian manuscript] that he did so in recompense to Msgr. Giovanni Battista Foppa, Orat., a noble of Bergamo [Ughelli-Colet Italia sacra VIII, 173-174: ad eius favorem cedente Cardin. Maculano], to whom he was much beholden when still only a member of the Dominican Order. Cardinal Maculano was considered papabile in the Conclave of 1644, and it is said that a powerful cardinal of one of the Courts gave him the exclusion, on the grounds that he was an enemy of Cardinal Mazarin [Touron, 454]. He advised Pope Innocent X (1644-1655) to send his sister-in-law, Olympia Maidalchini, away from the Papal Court—advice which was ignored, though it may have brought him some respect from the more serious cardinals. It is said that Donna Olimpia returned his negative opinion of her at the next Conclave, that of 1655, and worked to destroy his chances for the Papal Throne. Maculano himself, it is said, supported Cardinal Chigi in that election. A very unfavorable character portrait of him at the time is given by Gregorio Leti in Il Cardinalismo [Parte seconda (1668), pp. 291-292]. Despite Alexander VII's wish that all cardinals of religious orders should wear the same costume as the other cardinals, Maculano clung to the Dominican habit. He died on February 15, 1667, at the age of 88, and was buried at the Dominican church of Santa Sabina on the Aventine [A. Touron, Histoire des hommes illustres de l'Ordre de S. Dominique (Paris 1748), 449-458].

In the Conclave of 1644, the French Cardinals were opposed to Maculano, as was Cardinal Mazarin's brother, Michele Mazzarini, OP, Master of the Sacred Palace. - Francesco Peretti di Montalto (aged 49) [Roman], Cardinal Priest in the titulus of S. Girolamo dei Illyrici (Croati) (1642–1655). (died 1653) Member of the Spanish faction.

- Giovanni Giacomo Panciroli (aged 56) [Romanus], Cardinal Priest without titulus (created July 13, 1643) [titulus of S. Stefano in Monte Celio from November 28, 1644]. Doctor in utroque iure (from the Roman Archiginnasio, at the age of 18). Auditor of Cardinal Pamphili, both in Naples (1621-1625) and in Spain (1626). Honorary Chamberlain of Pope Urban VIII. Referendary and then Auditor of the Tribunals of the Signatures of Justice and Grace (1628-1632). Auditor of the Rota. He was Nuncio in Spain at the time of Pope Urban's death, and only arrived on the evening of the 12th of August [Siri, p. 581; Cardella VII, 21]. In the Conclave he did not support Cardinal Sacchetti, as a parente of the Barberini ought, but instead Cardinal Pamphili. He became Innocent X's Secretary of State (1644-1651). One of his conclavists was Decio Azzolini, a cleric of Fermo.

- Fausto Poli (aged 63) [Spoleto], Cardinal Priest in the titulus of S. Crisogono (1643–1653). Bishop of Orvieto (1644–1653).

- Lelio Falconieri (aged 59) [Florence], Cardinal Priest in the titulus of S. Maria del Popolo (1643–1648).

- Gaspare Mattei (aged 46) [Romanus],Cardinal Priest in the titulus of S. Pancrazio (1643–1648). Vice-Legate in Urbino and Commissary General in the Romagna. Nuncio in Vienna (1639–1643). Protector of Poland. Protector of the Kingdom of Naples. [left the Conclave on September 10: Gauchat, p. 27 n.2]. According to Bargrave's sources [p. 43], the Mattei family were angry at Cardinal Maculano for his high-handed confiscation and ruin of their property in the repair of his walls of the City of Rome.

- Cesare Facchinetti (aged 35) [Bologna], Cardinal Priest in the titulus of SS. Quattuor Coronatorum (1643–1671). Bishop of Senigaglia (1643–1655) and Titular Archbishop of Damietta/Tamiathis (1639–1672). Nephew of Pope Innocent IX. Lieutenant of Antonio Barberini.

- Girolamo Grimaldi (aged 48) [Genoa], Cardinal Priest. He had been in France earlier in the year 1644, and had been present along with Cardinal Mazarin at the consecration of Gondi de Retz as bishop of Corinth on February 16, 1644 [Memoires du Cardinal de Retz, part ii ch. 1 (ed. A. Champollion-Figeac I, p. 98)]. He had been given the red hat in secret consistory on July 13, 1644, by Urban VIII, and had his mouth closed. [given the titulus of S. Eusebio as of October 17, 1644, by Pope Innocent X, who presented him with the Cardinal's ring and opened his mouth]. Having once been a soldier, he started his ecclesiastical career as Cleric of the Apostolic Chamber. Governor of Rome. Nuncio in France (1641–1643). A member of the French faction. In March, 1645, he was eager to offer his services to Mazarin [Lettres du Cardinal Mazarin II, pp. 130-136, no. lvi].

- Carlo Rossetti (aged 30) [Ferrara], bishop of Faenza (1643–1681). Cardinal Priest without titulus [Bullarium Romanum 15, p. 357 col. 1] As Conte Rosetti he was sent to England as agent of Cardinal Barberini (but actually of Urban VIII), where he resided at court for nearly three years. Former titular archbishop of Tarsus (1641-1643). [left the Conclave on August 13, due to illness: Cancellieri, Stagioni, p. 58, from the Diary of Giacinto Gigli] He was opposed to Cardinal Pamphili's candidacy.

- Giambattista Altieri (aged 55) [Romanus], Cardinal Priest in the titulus of S. Maria sopra Minerva (1643–1654). Bishop of Todi (1643-1654). He was the second choice for Pope of the French Court [Siri, pp. 585-586].

- Mario Theodoli (aged 43), brother of the Marchese di Santo Vito. Cardinal Priest in the titulus of S. Bonifacio ed Alessio (1643–1649). Member of the French faction. Both the Cardinal and his brother received French pensions [Chéruel, Histoire de France II, p. 149]. But he voted with the cardinals who were attempting to exclude Sacchetti, for which the French branded him a traitor. He did, however, lead the support for the candidacy of Cardinal Maculano.

- Francesco Angelo Rapaccioli (aged 36) [Romanus], Cardinal Priest in the titulus of S. Maria in Via (1643–1650). Former Regent in the Apostolic Chancery (1634-1635). Cleric of the Apostolic Camera (1636). President of the Apostolic Camera. Treasurer General S.R.E. in the Apostolic Camera. Legate in Viterbo. Abbot Commendatory of S. Anastasio di Carbone. Bishop of Terni (1646-1656). He died on May 15, 1657 [Gauchat, Hierarchia catholica IV, p. 210 n. 6]. Supporter of Antonio Barberini.

- Francesco Adriano Ceva (aged 64), of the Marchesi de Ceva [Mondovi, Piedmont]. He began his career as Secretary to Cardinal Maffeo Barberini when he was Nuncio in France (1604-1607). He was Cardinal Barberini's conclavist in the Conclave of 1623. Canon of the Lateran Basilica (1623). Secretary of Memorials. Maestro di Camera. Nuncio Extraordinary to Louis XIII (1632-1634). Utriusque signaturae Referendarius. Secretarius a secretis of Urban VIII. Cardinal Priest in the titulus of S. Prisca (1643–1655). He died in Rome on October 12, 1655, at the age of 75, and was buried in the Oratory of S. Venanzio in the Lateran Baptistry [V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma VIII, p. 62, no. 164; p. 72, no. 193].

- Angelo Giori (aged 58) [Camerina], Cardinal Priest in the titulus of SS. Quirici et Julitta.

- Juan de Lugo, SJ (aged 60) [Madrid], Cardinal Priest in the titulus of S. Stefano in Monte Celio (May to October, 1644) [titulus of S. Balbina, from October 17, 1644]. Author of a work on the use of the exclusiva in the Conclave of 1644 (1655), in which he states clearly that Cardinal Sacchetti was given the exclusiva by the King of Spain because he was too close to Cardinal Mazarin. [Eggs VI, 386-389; Cardella VII, 47-49]. A loyal parente of the Barberini, and go-between with Cardinal Albornoz.

- Carlo de' Medici (aged 49) [Florence], Uncle of the Grand Duke of Florence, and Uncle of Marie de Medicis, Mother of Louis XIII. Cardinal Deacon of S. Nicola in Carcere (1623–1644). (died 1666). An enemy of the Barberini. Protector of Spain at the Court of Rome.

- Francesco Barberini (aged 46) [Romanus], Cardinal Deacon of S. Lorenzo in Damaso (1632–1644). Archpriest of the Liberian Basilica. Vice-Chancellor S.R.E. (1632–1679). Legate in France and in Spain (1625-1626) [See: Bazzoni]. (died December 10, 1679) Nephew of Urban VIII. Galileo's protector in Rome.

- Marzio Ginetti (aged 58) [Velitrae], Cardinal Deacon of S. Eustachio. Vicar General of Rome (died 1671). Creatura of the Barberini. Sent as Legate a Latere to Vienna (1635) and in Cologne (1636-1640) to attempt to arrange a universal peace, in which he was unsuccessful. Appointed Legate in Ferrara on his way back (1640-1643). Vicar of Rome (1629-1671).

- Antonio Barberini, iuniore (aged 37) [Romanus], brother of Cardinal Francesco Barberini, and nephew of Pope Urban VIII. Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Via Lata. Grand Prior in Rome of the Knights of S. John of Jerusalem (Knights of Malta). In August 1625 he was sent as Legate to France to deal with the dispute over the Valtelline. In March 1629 he was again sent as Legate to all of Italy, in particular to Bologna, Lombardy and Savoy, seeking peace. He was Protector of England and Scotland [Bullarium Romanum 14, no. 361, p. 136 (May 18, 1630)]. Since 1634, co-Protector of France before the Holy See (until Cardinal Maurice of Savoy resigned to marry). Legate in Bologna, Ferrara and Romandiola. Grand Aumonier of France from 1643. S.R.E. Camerlengo He was forced to flee Rome in 1645. He was made Archbishop of Reims in 1657, but Alexander VII refused him the pallium; it was granted by his successor, Clement IX, and Barberini took possession by procurator on October 4, 1667, and personally on December 22; he returned to Italy at the end of 1669. He died near Rome (at Castrum Nemiacum) on August 3, 1671.

- Girolamo Colonna (aged 40) [Romanus]; on the death of his elder brother in 1641 he became 7° Principe e Duca di Paliano, Gran Connestabile del Regno di Napoli, 5° Duca di Tagliacozzo, 3° Duca di Marino, etc. Cardinal Deacon of S. Angelo in Pescheria (from March 14 to December 12, 1644), previously Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Cosmedin (1639–1644), and of S. Agnese in Agone (1628–1639). Archbishop of Bologna (1632–1644). Archpriest of the Lateran Basilica (1628-1666). He died on September 4, 1666. A member of the Spanish party. A supporter of Cardinal Pamphili.

- Giangiacomo Teodoro Trivulzio (aged 47) [Milan], Cardinal Deacon of S. Cesareo (1629–1644). (died 1656)

- Giulio Gabrielli (aged 40) [Roman], Cardinal Deacon of S. Agatha (1642-1655) Bishop of Ascoli Piceno (1642–1668), where he lived. (died 1677)

- Virginio Orsini (aged 29) [Roman], Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Cosmedin (1644–1653). (died 1676)

- Rinaldo d'Este (aged 26) [Modena], Cardinal Deacon without deaconry [Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria Nuova (from November 28, 1644, for a total of two weeks)]. Protector of France before the Roman Curia (died 1672)

- Vincenzo Costaguti (aged 32) [Genoa], Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Porticu (1643–1652).

- Giovanni Stefano Donghi (aged 34) [Genoa], Cardinal Deacon of S. Georgio ad velum aureum (1643–1655).

- Paolo Emilio Rondinini (aged 27) [Roman], Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Aquiro (1643–1655).

- Achille d'Estampes de Valençay, Member of the Order of S. John of Jerusalem (aged 51) [Tours], Cardinal Deacon of S. Adriano (1644–1646). General of the Papal Army (1642-1644).

- Gaspar Borja y Velasco (aged 64), son of the Duke of Gandia. Bishop of Albano (1630–1645) and Archbishop of Seville (1632–1645). He was forced to leave Rome in 1635 for his diocese in Spain due to a Bull issued by Urban VIII on episcopal residence [Bullarium Romanum 15 (Torino 1868), no. DIV, pp. 457-462], specially designed (it seems) to get rid of Borja. His career began as Canon of Toledo, at the nomination of the King of Spain. Spanish Ambassador in Rome (1616-1619 and 1631-1635); Viceroy in Naples 1620; Governor of the Kingdom of Spain (1642-1643). (d. December 28, 1645) (He and his alleged conclavists are not in the Conclavist list) (Cardella 6, 170-172, implies he stayed in Spain by not listing him as attending the Conclave of Innocent X; Gauchat, p. 12 no. 29)

- François de la Rochefoucald (aged 86), Cardinal Priest of S. Callisto (1610–1645). former Bishop of Senlis (1610–1622). (died February 14, 1645) (Gauchat, p. 10 no. 11)

- Baltasar de Moscoso y Sandoval (aged 55), son of Don Lope de Moscoso Ossorio, 6th Conde de Altamira; and Doña Leonor de Sandoval y Roxas (daughter of the 4th Marques de Denia); Cardinal Baltasar's uncle was Cardinal Bernardo de Roxas y Sandoval, Archbishop of Toledo (1599-1618). Bachelor of Canon Law (Salamanca, 1610); Doctor of Canon Law (Siguenza, 1615). Dean of Toledo (1614). He was created cardinal by Pope Paul V in the Consistory of December 2, 1615, at the request of the King of Spain. He was ordained a priest on February 27, 1616, by Francisco Suarez, Bishop of Medauro. Cardinal Priest of S. Croce in Gerusalemme (1630–1665). Bishop of Jaén (1619–1646), consecrated by Fernando de Azebedo, Archbishop of Burgos (1613-1630). (died 1665) [Gauchat, p. 13 no. 36]. John Bargrave, Pope Alexander VII and the College of Cardinals, states (p. 14) that he never came to any conclave. [Fray Antonio de Jesus Maria, O.Carm., D. Baltasar de Moscoso y Sandoval, Presbytero Cardenal (Madrid 1680)]

- Agustin Spinola Basadone (aged 47), titulus of S. Bartolomeo all' Isola (1631–1649). Archbishop of Santiago de Compostela (1630-1645) (died 1649) (Gauchat, p. 15 no. 60)

- Jules Raymond Mazarin (aged 42) [Pescina (Abruzzo), Kingdom of Naples; but his family was registered in the parish of SS. Vincenzo ed Anastasio, in the Rione di Trevi in Rome (A. Rénée, Les nièces de Mazarin, p. 435)], Cardinal Priest without titulus. Started his career in Rome as chamberlain to Constable Filippo Colonna (6th Principe e Duca di Paliano and Grand Constable of the Kingdom of Naples), brother of Cardinal Girolamo Colonna. He studied at the Collegio Romano in Rome, but then accompanied Girolamo Colonna to the University of Alcalà de Henares in Spain as his chamberlain (1621-1623). He returned to Rome and earned a doctorate in utroque iure from the Sapienza in Rome (1628). Former Sommista of Cardinal Barberini, the Vice-Chancellor. He negotiated the treaty of Cherasco in 1631, bringing to an end the war between France and Spain over the succession to the Duchy of Mantua; his abilities brought him to the attention of Cardinal de Richelieu, the French First Minister. He was appointed Vice-Legate in Avignon in 1632-1636. He became a naturalized French citizen in 1636. [Gauchat, p. 25 no. 55]. Made a Cardinal at the request of Louis XIII, with the recommendation of Cardinal Richelieu, in December, 1641. First Minister of Louis XIII, upon the death of Cardinal Richelieu (1642-1643), and of Louis XIV (1643-1661). He was never ordained priest or consecrated bishop. (died March 9, 1661).

Mazarin was at Fontainebleau with the Court when Pamphili was elected. He wrote to the new Pope Innocent X from Paris on October 15, 1544 [Lettres du Cardinal Mazarin, pendant son Ministère II (Paris 1879), pp. 88-90, no. xliii]; he was ill during the month of October, as he states in the letter, and not yet fully recovered: Raccoglio tutte le forze, che mi avanzano da una lunga e pericolosa malatia, della quale non sono ancora affatto libero, per non differire d' avantaggio la mia riverente espressione per l'allegrezza che mi hà recato la nuova dell' assuntione di Vostra Santità al Pontificato.... His letters of 1644 indicate that he was much more occupied with the war in the Netherlands, Catalonia, Lorraine, Bavaria, and Germany [Lettres du Cardinal Mazarin, pendant son Ministère I (Paris 1872), passim; and II (Paris 1879), passim]. In his biographical notes on Mazarin, Salvador Miranda asserts that Mazarin "Arrived too late to the conclave of 1644, which elected Pope Innocent X, to present the French veto against Cardinal Giambattista Pamphilj, who had already been elected pope and taken the name Innocent X." This is false. Mazarin, as his letters indicate, did not go to Rome at all in this year. On November 25, he wrote a blistering letter to his brother, Michele Mazzarini, OP [Lettres du Cardinal Mazarin II, pp. 98-105, no. xlvi], the contents of which require one to think that Mazarin had not been to Rome as of that date—seventeen weeks after the beginning of the Conclave.

Courts and Factions

The French (the Queen Mother, Anne "of Austria"—actually the sister of Philip IV of Spain—taking an active role) were determined that no member of the 'Old College', that is to say the creatures of Paul V, whose policy had been pro-Spanish and anti-French, would be elected to the Papal throne. Their instructions were to be carried out by Cardinal Bichi and Cardinal Richelieu of Lyon, seconded by the French Ambassador in Rome, Melchior Mites de Chevrières, Marquis de Saint-Chamont [Lettres du Cardinal Mazarin I, pp. 552-553, no. cccxcvi; Chéruel, Histoire de France, pp. 142-143; Maurice de Boissieu, Généalogie de la Maison de Saint-Chamond (Saint-Étienne 1888), pp.133-182]. Cardinal Pamphili was to be the recipient of the exclusiva if necessary—though Cardinal Mattei was concerned as to the possible effect upon the Cardinals if the actual veto were to be presented. Cardinal Antonio Barberini's chosen candidate was Cardinal Giulio Cesare Sacchetti, whom the French were prepared to support, as a candidate highly favorable to the French interest. Mazarin, in fact, wrote to the Comte de Saint-Chamont [Lettres du Cardinal Mazarin II, p. 249, n. 2]:

The French (the Queen Mother, Anne "of Austria"—actually the sister of Philip IV of Spain—taking an active role) were determined that no member of the 'Old College', that is to say the creatures of Paul V, whose policy had been pro-Spanish and anti-French, would be elected to the Papal throne. Their instructions were to be carried out by Cardinal Bichi and Cardinal Richelieu of Lyon, seconded by the French Ambassador in Rome, Melchior Mites de Chevrières, Marquis de Saint-Chamont [Lettres du Cardinal Mazarin I, pp. 552-553, no. cccxcvi; Chéruel, Histoire de France, pp. 142-143; Maurice de Boissieu, Généalogie de la Maison de Saint-Chamond (Saint-Étienne 1888), pp.133-182]. Cardinal Pamphili was to be the recipient of the exclusiva if necessary—though Cardinal Mattei was concerned as to the possible effect upon the Cardinals if the actual veto were to be presented. Cardinal Antonio Barberini's chosen candidate was Cardinal Giulio Cesare Sacchetti, whom the French were prepared to support, as a candidate highly favorable to the French interest. Mazarin, in fact, wrote to the Comte de Saint-Chamont [Lettres du Cardinal Mazarin II, p. 249, n. 2]:

Sa Majesté désire que l' on fasse tous les efforts possibles pour faire réussir Sachetti, en qui se rencontrent, avantageusement, toutes les conditions pour un bon pape.

The second choice of the French was Cardinal Altieri. Their biggest concern was Cardinal Bentivoglio, the Bishop of Palestrina. He was one of the 'Old Cardinals' created by Paul V, and therefore thought to be pro-Spanish. He appeared, however, to be friendly to the France where he had been Nuncio from 1616-1621. Since the Spanish appeared to be pressing forward names of Cardinals of considerable seniority, Bentivoglio might well be a viable candidate for the French. His death during the Conclave was a disappointment to the French. After him was to come Cardinal Crescenzio, the 72 year old Bishop of Porto. Next was Cardinal Cennino, who had been ambassador of the Holy See in Spain (1618-1621), and who was currently Suburbicarian Bishop of Sabina.

The Imperial Ambassador to the Conclave was Duke Federico Savelli. Odoardo Farnese, Duke of Parma, sent the Marchese of Soriano, to do whatever he could to ruin the Barberini.

The Conclave

The Novendiales concluded on August 8, 1644, with a funeral oration pronounced by Msgr. Felice Contelori, Prefect of the Vatican Archives [Novaes, Introduzione I, 265]. On the same day, the Ambassador of Spain, the Conde di Sirvella, arrived in Rome.

The Conclave of 1644 began on Tuesday, August 9, though the closing of the doors did not take place until the next day. The oration de eligendo pontifice was pronounced by Jacobo Accarsio, Bishop of Vestana (Vieti) (1642-1644). Fifty-six (or 55) cardinals entered Conclave [Siri, Mercurio, p. 592], among whom a considerable number were considered 'soggetti papabili'. The leading candidate, promoted by Cardinal Antonio Barberini, nephew of the late Pope Urban VIII, was Cardinal Giulio Cesare Sacchetti; both cardinals were adherents of the French party, and they had close to forty votes. Six cardinals did not enter Conclave on the opening day: Rochefoucauld, Sandoval, Spinola, Panziroli, Mazarin and Orsini. Orsini was in Rome, but was ill. In any event, due to the difficulty in securing the Conclave area, there was no scrutiny on the first day. Panziroli arrived from Spain, where he had been Nuncio, on August 13. The King of France, Louis XIV (or rather his managers, Mazarin and Queen Anne, since Louis was a child of six), was not eager to have the Conclave proceed until the French agent, carrying the royal instructions, arrived in Rome [Petruccelli III, 230]. Mazarin's secretary, Alessandro Fabri, was supposed to bring the 'sicuro capitale' and pass it to Cardinal Barberini viva voce, as well as to provide secret official written instructions to the Ambassador, the Marquis de Saint-Chamont, but Fabri fell seriously ill just before his departure from Paris [Lettres du Cardinal Mazarin II, p. 25-27, no. xii (August 11, 1644)]. Fabri, once recovered, did arrive in Rome, toward the end of the Conclave [Siri, 679], and did bring specific orders to Barberini, for the exclusion of Pamphilio (at least according to Siri, the official French historian, writing a decade after the event); these instructions seem to have been a reiteration of earlier ones, not a response to Ambassador Saint-Chamont's express courier bringing a request to withdraw the exclusiva against Cardinal Pamphili. Fabri is also mentioned as being in Rome shortly after the Conclave [Instructions for the Sieur de Grémonville]. The Instructions, which in fact carried the fatal word against Cardinal Pamphili, were issued on September 5 and 6, but they did not reach in Rome until September 19 [Siri, p. 695]. Cardinal Bichi was also sent copies of the Instructions [Siri, p. 708]. By the time the exclusiva againt Pamphili arrived, Innocent X had been Pope for five days.

August 9 brought a moment of high drama. The Spanish Party, led by Conde Sirvela and Cardinal Albornoz, in association with the Imperial Party, led by Duke Paolo Savelli, Cardinal Colonna (the Cardinal Protector) and Cardinal Harrach, presented the formal veto against the candidacy of Cardinal Sacchetti [Siri, Mercurio p. 592; Wahrmund, Ausschliessungs-recht, p. 129; "Beiträge...", pp. 3-5; portrait of Sacchetti at right]. Urban VIII and his family had been so outrageously partial to the French that the Imperialists and the Spanish were determined that no supporter of French interests would sit on the Throne of Peter. In a note, seeking clarification of what had been done and by whom, Cardinal Valenti wrote to Duke Savelli on August 27, 1644, more than two weeks after the event [Wahrmund, Ausschliessungs-recht, p. 133 and 273]:

August 9 brought a moment of high drama. The Spanish Party, led by Conde Sirvela and Cardinal Albornoz, in association with the Imperial Party, led by Duke Paolo Savelli, Cardinal Colonna (the Cardinal Protector) and Cardinal Harrach, presented the formal veto against the candidacy of Cardinal Sacchetti [Siri, Mercurio p. 592; Wahrmund, Ausschliessungs-recht, p. 129; "Beiträge...", pp. 3-5; portrait of Sacchetti at right]. Urban VIII and his family had been so outrageously partial to the French that the Imperialists and the Spanish were determined that no supporter of French interests would sit on the Throne of Peter. In a note, seeking clarification of what had been done and by whom, Cardinal Valenti wrote to Duke Savelli on August 27, 1644, more than two weeks after the event [Wahrmund, Ausschliessungs-recht, p. 133 and 273]:

... Matteo Sacchetti fratello del Cardinale non cessava d'andarsi aiutando coll'Ambasciador di Spagna, che per certo termine di torto gli parlava in modo, che non si poteva determinare, se l'esclusione, che si faceva al Cardinale, era per ordine del Rè, o per risolutione de ministri. Questo non piacendo alla fattione Spagnuola, han voluto, che l'Ambasciator dica apertamente, ch'è per ordine del Rè, com' è effetivamente, e cosi de prencipi proprii aderenti à Spagna i ministri loro, per idsanimar maggiormente gli avversarii, à chi in ciò non resti più speranza di conseguire, che l' esclusione si revochi. Tanto più operava questo, quanto per l'aversione di tutta la casa d' Austria e de gl' altri prencipi à essa congiunti di sangue e d' interessi publicamente dichiarata, Sacchetti non può tuta conscientia esser' eletto, come si prova per una scrittura fatta dal Padre Valentini, confessore del Conclave, che và per manus de Cardinali, che mostra non potersi fare per l' occasione, che si darebbe à tutti questi prencipi di sequestrarsi dal commercio della sede Apostolica in tutte quelle cose, che non aspettano alla fede ò religione. Il Padre è della compagna di Giesù, e tanto più si crede irriuscibile la prattica de Sacchetti, li Barberini però non s'abbandonano...."

The purpose, of course, was to attempt to have the exclusiva revoked. If the exclusiva had come from the Ministers rather than from the King of Spain, then there would have been room to correct the misstep of the underlings. Unfortunately, as Barberini learned later in a conversation with Cardinal Albornoz, when he put the question directly, it was the King himself, in no less than fourteen separate letters, who had issued the exclusiva [Siri, p. 617]. The presumptuous intrusion of Father Valentino into the proceedings may, in fact, have helped to change the course of the Conclave, providing a rationale for what many considered to be an arbitrary exercise of power. Cardinals never liked the exercise of this "privilege", which was enshrined in no Bull or Constitution or even Motu proprio, and which limited their freedom to select a candidate whom they considered appropriate. The exclusiva is attacked in a piece written by Cardinal Francesco Albizzi (1654-1684).

The imposition of the exclusiva also galvanized Cardinal Antonio Barberini, who was the principal promoter of the candidacy of Cardinal Sacchetti, in obedience to the commands of the French King. Barberini immediately conferred with his uncle (who was not a member of his party), and convinced him to speak with the "old cardinals" (those created by Paul V). The argument used was that the Barberini were prepared to stay in conclave until everyone died before they allowed someone who was not a member of their faction to be elected pope, and that their candidate was Sacchetti. The approach produced the opposite effect to what was intended, and impelled the Vecchi to thwart the efforts on behalf of Sacchetti. The only result was dissension among the three Barberini, each of whom was then too involved in his own interest to embrace a common course of action [Siri, 598]. Antonio Barberini, junior, spent a great deal of time trying to convince his brother and the French not to proceed immediately to the open exclusion of Pamphili. Antonio Barberini, in fact, had a high opinion of Pamphili, despite the distaste of the French Court. Pamphili had been negotiating for the marriage of his only nephew, Don Camillo Pamphili, to one of the Barberini women. But Barberino seems to have been unaware of the depths of loathing against him on the part of Cardinal Pamphili. Nonetheless, it was easily discovered that a virtual exclusiva was at work against Pamphili, comprising some 22 votes, most of them from the French faction [Siri, p. 605].

Maculano

For Antonio Barberini, junior, therefore, the pressing need was for a candidate from his faction who had plausibility, but who would not arouse the rest of the members of his faction to desert the faction because they could not, or would not, support the proposed candidate. They chose Cardinal Maculano [Siri, Mercurio p. 607]. Barberini managed to enlist Cardinals Grimaldi, Valanze [Achille d'Estampes de Valençay], and Trivulzio in his efforts. The hopes of Cardinal Vincenzo Maculano, OP, were bolstered by support from the Spanish faction, but they made a number of conditions which did not sit well with many Cardinals. Maculano's votes reached their high point on Friday, August 12, when he received eighteen votes in the morning Scrutiny (seventeen, according to Siri, p. 608). Cardinal Barberini, junior, remarked, in a Memorial on August 19 [Siri, p. 633], that Maculano was being considered because, next to Pamphili, he was the oldest person on their list of soggetti:

For Antonio Barberini, junior, therefore, the pressing need was for a candidate from his faction who had plausibility, but who would not arouse the rest of the members of his faction to desert the faction because they could not, or would not, support the proposed candidate. They chose Cardinal Maculano [Siri, Mercurio p. 607]. Barberini managed to enlist Cardinals Grimaldi, Valanze [Achille d'Estampes de Valençay], and Trivulzio in his efforts. The hopes of Cardinal Vincenzo Maculano, OP, were bolstered by support from the Spanish faction, but they made a number of conditions which did not sit well with many Cardinals. Maculano's votes reached their high point on Friday, August 12, when he received eighteen votes in the morning Scrutiny (seventeen, according to Siri, p. 608). Cardinal Barberini, junior, remarked, in a Memorial on August 19 [Siri, p. 633], that Maculano was being considered because, next to Pamphili, he was the oldest person on their list of soggetti:

ad altri habbiamo messo in campo il Cardinale S. Clemente [Vincenzo Maculani, OP], come il più vecchio dopo Pamphilio suddetto; e forse la pratica di lui sarebbe andata, benche non habbia molto aura, piu innanzi pe'l desiderio, ch' è nell' universale di un Papa vecchio, se io non havessi havuto più à cuore gl' interessi del Signor Cardinale Mazzarini, che le convenienze della fattione Urbana.

In the afternoon, however, Maculano's support had dropped by five. He had his opponents, from both parties, who had been activated: Montalto, Bichi, Richelieu, Theodoli, and Barberini OFM Cap. [Siri, Mercurio, p. 646]. In fact he had an enemy, who was working vigorously against his interests, Msgr. Michele Mazzarini, OP, the Master of the Sacred Palaces—whose ambition had been to be Master General of the Dominicans [Lettres du Cardinal Mazarin Tome I (Paris 1872), pp. 17-22, no. iv; Catalano, De magistro sacri palatii, 151-156]. The Jesuits and their supporters (including Cardinal Lugo) were also opposed to his candidacy, simply (it is said) because of emulation between the two religious orders [Siri, pp. 608, 654]. It was also alleged that Maculano was close to the Duke of Parma, Odoardo Farnese, but it was also pointed out that Farnese was not involved in trying to make a pope. What seemed to be a promising beginning turned out to be a field filled with difficulties. The politicking for him was suspended for the moment [Siri, Mercurio, p. 608].

Cardinal Giovanni Giacomo Panciroli arrived in Rome from his post as Nuncio to Spain on the evening of the 12th of August [Siri, p. 581; Cardella VII, 21]. According to Battista Nani (who was Venetian Ambassador to the French Court from 1644 to 1648), Panciroli carried Instructions from the Spanish Court [Historia de la Republica Veneta, parte seconda, Libro Primo p. 3]:

Il Cardinal Albornoz, che dirigeva il partito Spagnuolo, publicamente al solo Sachetti opponeva, ma sotto mano attraversava d' ogn' altro le prattiche, affine d' eseguire gli ordini, che il Pancirolo ritornato da quella Nunciatura gli haveva portato, di promuovere unicamente Pamfilio, ma per giunger' al segno, bisignova vincer' Antonio, nè ciò si poteva senza ingannar' i Francesi. Pancirolo dunque vi s' impiegò con artificj, e lusinghe, dando speranza di matrimonio di una figliuola del Prefetto in Camillo Pamfilio unico Nipote del Cardinale.

On Thursday, August 18, the Scrutiny was prolonged to a length of five hours, due to a number of errors. Cardinal Crescenzi (because of his age, it is said), in submitting his ballot, forgot to insert the name of the candidate for whom he was voting; he asked the Infirmarii to return his ballot so that he could add the name to it, but they were unwilling to do so without authorization from the Sacred College, where there then ensued a lengthy debate. The Dean was willing to accommodate the sick Cardinal, but Cardinal Antonio Barberini objected, on the grounds that the act had been completed when submitted to the Infirmarii and that it should be counted as "Nemini". A vote was finally taken and 24 cardinals voted to count Crescenzi's ballot as "Nemini", while 28 voted to allow him to make a new ballot—to the great embarassment of the Barberini faction. The Scrutiny was annulled anyway, due to the absence of one ballot, and another Scrutiny was ordered. On August 18, Cardinal Francesco Cennini de' Salamandri (called the Cardinal of S. Marcello) received 21 votes on the Scrutiny (twenty-four after the accessio)—a good sign in the view of Cardinal Barberini [Siri, p. 640; cf. p. 608; Cardella VII, p. 8]. Cennini, however, was a candidate favored by the Spanish, was one of the "Old Cardinals" of Pope Paul V (Borghese), and was not a member of the Barberini faction. His vote count was a sufficient number, though, to guarantee a virtual exclusiva against any other candidate. His candidacy, however, was hampered by his own age; the strain of his candidacy revealed his physical weakness, and he was seen as unfit for the Papal throne. His supporters transferred their votes to Cardinal Sacchetti [Siri, p. 609].

Around this time the French Ambassador, Saint-Chamont, became alarmed by the movement of Spanish Neapolitan troops on the southern border of the Papal States. He feared that this might be an invasion, with the purpose of capturing the College of Cardinals and forcing the election of a pope favorable to the Spanish interest. He therefore rushed to the Conclave and obtained an interview with the Heads of the Orders at the gate of the Conclave. He offered the Cardinals the full support of the French, and informed them that the Marshal de Brézé was at Marseille, with a fleet and troops, prepared to rush to the assistance of the College of Cardinals (He was in fact heading for Catalonia). There were also French troops in Lombardy and Savoy who could be called upon to defend the Papal States if need be. Cardinal Crescentio thanked the King of France cordially for his offer. When the Spanish ambassador heard what had happened, he immediately, the next day, headed for the Conclave and made similar offers in the name of the King of Spain. He too was cordially thanked. Presently, on August 21, Cavaliere Gondi, the representative of the Grand Duke arrived at the entrance to the Conclave, and announced that the Prince of Parma was also ready to intervene to help the Sacred College. Cardinal de' Medici immediately sent the Count of Carpegna to Caprarola, with urgent advice to remove the offending troops from the papal borders. Nothing came of all this posturing, though, at the moment, it must have unnerved the members of the Sacred College. On August 23, Mangelli, the Agent of Parma, appeared, demanding relief from the exactions of the papal government, on the grounds that they were contrary to a treaty signed personally by the Barberini Pope, Urban VIII. Such was neither the time nor the place for such matters. According to canon law, the Cardinals had power to do nothing except elect a pope; they certainly could not revise a treaty, nor order papal officials not to carry out their statutory duties. The matter was turned over to an Advocate of the Sacred College to prepare a reply to the Duke of Parma. But Parma was taking advantage of the moment to embarass Cardinal Antonio Barberini and his anti-Spanish efforts. Finally the Spanish Ambassador reappeared at the gate of the Conclave, to smooth over (ritorcere "twist around") the disagreement with the Sacred College.

Barberini begins to trim

On Wednesday, August 24, Antonio Barberini sent off to the French Ambassador and the Chargé d' Affaires a memorandum, which proposed the candidacy of Cardinal Pamphili, and enumerated the reasons both in favor and against his candidacy. Saint-Chamont replied immediately, on the next day, advising the Cardinal to stick to the royal Instructions [Siri, p. 649]: Questo nuovo corriere mi ha confermata di nuovo l' intera protettione della Francia per la persona e casa di V. Em.; e pero io la supplico di fare ogni sforzo in questa occasione per servire la Maesta loro secondo le sue intentioni. E perche ho ragionato ampiamente di questo negotio col Signor Vincenzo Martinozzi, io mi rimettere a lui. Barberini's thoughts, he said, were contrary to the wishes of the Queen, as expressed both in the original Instructions and in the updated ones: i suoi sensi perche sono interamente contrarij à quelli della Regina, non solo nella prima instruttione, che V. Em. ha letta, mà ancora nella seconda, che hebbi hieri per un corriere straordinario. On Friday, August 26, Barberini sent another long memorandum on the subject of Pamphili, entitled Epilogo delle cose, che occorrono al Signor Cardinale Antonio in proposito dello spaccio pervenientoli il giorno di S. Luigi dal Signor Ambasciadore di Francia, e dal Signor Vincenzo Martinozzi. The Ambassador replied immediately, on the 27th, in very plain and emphatic terms [Siri, pp. 651-652]: Il Signor Martinozzi, e me siamo stati questa mattina trè hore insieme a parlare di Pamphilio, mà dopo haver ben pesato, et esaminato tutte le ragioni, e considerationi che vi si possono apportare; io non trovo di protettione per la vostra casa, solida, che quella del Re: e questa è interamente nelle vostre mani con l' elettione di un Papa tale quale desidera S. M. et vio conformandoni alle sue volontà. (Martinozzi was a close personal friend of Mazarin; his son was married to Mazarin's sister) Barberini went back to the campaign for Sacchetti, but the business of Pamphili was not done.

On Tuesday, August 30, after the customary Mass of the Holy Spirit, yet another Scrutiny began. The first vote read out was for Sacchetti [Histoire des conclaves 2, p. 458]. Antonio Barberini had been working hard for his and the French Court's chosen candidate, and he expected that Sacchetti would receive twelve votes on the Scrutiny, and at the Accessio would obtain twenty-six more, for a total of thirty-eight. This was one more than necessary for a canonical election. Barberini believed he had beaten the Spanish exclusiva. Imagine the depth of his disappointment and mortification when Sacchetti received only five votes on the Scrutiny and an equal number on the Accessio! [Siri, Mercurio, p. 622]. The Barberini faction was beginning to wander.

On Sunday, September 4, the French Ambassador Saint-Chamont wrote to Cardinal Antonio Barberini in the Conclave, advising him that he did not consider it to be Barberini's fault as to what had happened in the campaign for Cardinal Maculani. At the same time he advised him to keep the Conclave going and not to do anything as far as Pamphili was concerned until specific instructions had been received from France. The Ambassador had sent off a fast courier; an answer could be expected in twenty days [Siri, 676]. Barberini, nonetheless, was to use every means to make sure that France had enough votes for Pamphili's exclusion. On the 5th, the Ambassador went so far as to threaten Barberini with disgrace and worse if he did not adhere to the instructions sent from the French Court [Siri, p. 670]:

Mà io non comprendo punto la pretestatione di V. E. nella sua prima lettera; nè la preghiera, ch' ella mi fà nella seconda di scaricarla del peso de gli affari del Re, ch' ella nomina insoportabile; poiche ella sà benè, ch' io son manchevole di potere, e che quando l' havesse, non supro i impiegarlo à ciò, per lo meno che n' essere suo nemico giaruto; non stimando già, che alcuno de' vostri servitori, vi possi duro un simile consiglio; nè che V. E. stessa lo voglia seguire dopo haverlo ben pesato. Onde io non ne scrivero punto in Corte: ma diro bene francamente a V. Em. che l' autorità del Re e ad un punto, che vi sono pochi Principi in Europa per rilevati, che sieno, che non desiderivo d' essere honorati de' suoi comandamenti, et a' quali non sia insopprotabile d' esserne privi. A che io aggiungo, che se l' elettione, che si sara in Conclave non piacera alle Loro Maestà, la Chiesa vi perdera molto e V. Em. e la vostra casa ne ricevera il danno, e gran perdita di riputatione d' havere lasciato correre alla Francia un tale scacco sotto la sua protettione.

This was certainly going too far. Barberini was not the chamberlain of the King of France, to be ordered about like a servant; he was the Chamberlain of the Holy Roman Church and the late Pope's nephew. But the Ambassador added a note of his own to the dispatch of Barberini's memorandum of August 26 to the French Court —unfortunately for his future— endorsing Barberini's observations, and seconding the idea that it was necessary to save the situation, or put the best face on it, by actually promoting the candidacy of Pamphili [Siri, 666].

Barberini complained in return that his efforts were being complicated by Fr. Michele Mazzarino, OP, the Master of the Sacred Palace, and brother of Cardinal Mazarin. Father Mazzarino was conducting his own campaign of exclusion against Cardinal Vincenzo Maculani, OP, the Cardinal of S. Clemente, which was dividing both the French and Barberini's creature. But there seemed to be no way that Cardinal Barberini could satisfy both French demands. He wrote to the Ambassador Saint-Chamont on September 9 [Siri, p. 671]:

Non lasciai ancora di dire in qualche proposito, ch' era molto fallace il giudicio delle cose, che si dava fuori del Conclave perche quivi era sempre convenuto à tutti mutar più, e più volte le determinationi; e che hoggi con la Bolla era certo, che più sarebbe occorso di farlo. Ne sarà nuovo, che io le dicessi, che non mi sarei caricato d' altre esclusioni particolarmente contra le creature per non rendermi affatto esoso alla fattione; oltre ch' è certo, che due esclusioni non possono mantenersi; il che non lascio di notificare à V. E. anche in continentione del zelo immutabile, che hò per la Francia, non mi potendo nè meno dar maggior forza à mantenere due esclusioni, anche il non nascer questa di S. Clemente dal puro riguardo del P. Mazzarini, ma da relationi havutesi in Francia del detto Cardinale, quali saranno certamente procedute da chi gli vuol male, essendo io assai informato de' suoi affari.

The Ambassador replied on the next day that it was true that two exclusiva were difficult to manage—if they were formal and public; but neither Pamphili's nor Maculani's had been publicly announced, and as far as he knew from Barberini himself, there was no intention of making them public and official. In fact, Antonio Barberini had the promise of twenty-five cardinals NOT to vote for Pamphili without his consent [Siri, p. 642]. That was certainly a virtual exclusiva. It was his brother, Francesco Barberini, however, who wanted to make Pamphili's exclusion a public matter, and he was pressing both Antonio and Cardinal Bichi to do so [Siri, 643-644]. Cardinal Rapacciolo, suspecting that Francesco Barberini was up to something, obtained a written promise from Cardinal Bichi not to discuss the subject of Pamphili without the presence of Cardinal Antonio Barberini. Francesco was indeed up to something, the candidacy of Cardinal Pamphili. Antonio's own party was becoming very difficult to control. A month locked up in the Vatican Apostolic Palace in the heat of a Roman summer cannot have helped matters.

Election of Cardinal Pamphili

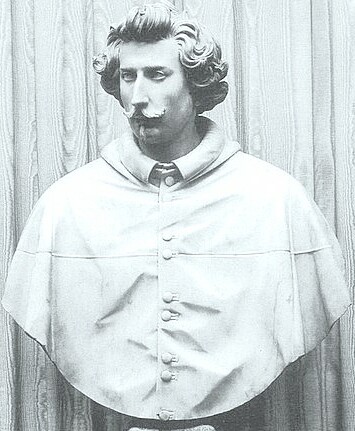

Barberini finally decided to open negotiations with the Spanish. He held a conversation with the Jesuit Cardinal Lugo, and convinced him to speak with Cardinal Albornoz, and present a number of propositions to him. He let it be known that he was not going to exclude Cardinal Pamphili [portrait bust at left], but he did want the Spanish to withdraw the exclusiva against Cardinal Sacchetti. On the Spanish side, the problem was that the only instruction they had received was the exclusion of Sacchetti (or at least that is what Siri believed). Besides that, they had no direction as to what to do next, or whom to offer as an alternative. Albornoz consulted with the Spanish Ambassador (though not with Cardinal de' Medici, the Protector of Spain at the Holy See), who reacted suspiciously, pointing out that the minute the exclusiva was removed, Barberini could ram through the election of Sacchetti. After all, it was a secret vote. Only the election of Pamphili could protect Spain from that threat. Lugo therefore had to report back to Bernini that the exclusiva against Sacchetti could not be lifted, since it was the will of King Philip IV.

Barberini finally decided to open negotiations with the Spanish. He held a conversation with the Jesuit Cardinal Lugo, and convinced him to speak with Cardinal Albornoz, and present a number of propositions to him. He let it be known that he was not going to exclude Cardinal Pamphili [portrait bust at left], but he did want the Spanish to withdraw the exclusiva against Cardinal Sacchetti. On the Spanish side, the problem was that the only instruction they had received was the exclusion of Sacchetti (or at least that is what Siri believed). Besides that, they had no direction as to what to do next, or whom to offer as an alternative. Albornoz consulted with the Spanish Ambassador (though not with Cardinal de' Medici, the Protector of Spain at the Holy See), who reacted suspiciously, pointing out that the minute the exclusiva was removed, Barberini could ram through the election of Sacchetti. After all, it was a secret vote. Only the election of Pamphili could protect Spain from that threat. Lugo therefore had to report back to Bernini that the exclusiva against Sacchetti could not be lifted, since it was the will of King Philip IV.

At the same time, Barberini was attempting to put together a group of his cardinals who would vote for Pamphili. As he wrote to the Ambassador:

si tratta di fare Papa il Signor Cardinale Pamphilio, et à questo io non posso rimediare, e vado considerando, che saria più servitio della Francia l' acconsentirvi, che 'l dissentirvi acciò potiamo havere un Papa amorevole, et obligato; e non haverlo contrario, e disgustato.

A committee was put together to see if they could come together and agree on a candidate; the Spanish appointed Cardinal Capponi and Cardinal Cornaro; Antonio Barberini appointed Cardinal Poli [Siri, p. 676]. Pamphili himself kept remarking that he was not interested in being elected Pope, protective coloration no doubt to deflect the attention of the French cardinals from the prattica of Francesco Barberino on his behalf. He also had to hide his true feelings about Cardinal Antonio from Antonio himself. Antonio Barberini had to use great caution, so as not to provoke Cardinal Bichi to announce an exclusiva against Pamphili on behalf of the French. It is true that the French Court had not authorized a public and official exclusiva, but Bichi could still be frightened into making an announcement anyway in the assurance that he was doing what was right for the French Crown. His agreement not do discuss Pamphili except in the presence of Antonio Barberini had many loopholes in it. Any move by Bichi might destroy the campaign for Pamphili.

On Saturday, September 10, Cardinals Gaspare Mattei [Siri, pp. 654-655] and Giulio Gabrielli left the Conclave, due to illness, though Cardinal Gabrielli returned on the morning of September 15, in time to vote in the last scrutiny. Concerning Cardinal Mattei, one of the avvisi, dated September 17, reported [V. Forcella, Catalogo dei manoscritti relativi alla storia di Roma III (Roma 1881), p. 326, Codex Ottobonianus Latinus no. 3348]:

Il Sig.e Cardinale Mattei continuando à star male nel Conclave con la febre finalmente per conseglio de Medici usci Sabbato matina da quella, et andò à curarsi in Casa sua.

Mattei and Orsini, though they were still outside the Conclave due to illness, were available to be summoned immediately if necessary. In the judgment of Cardinal Albornoz, the leader of the Spanish faction, however, their participation was not necessary. The number of Cardinals present at that time, therefore, was 54 [Siri, p. 685; Gauchat, p. 27 n. 2]. The number needed to elect was 36.

The French Ambassador, Saint-Chaumont, advised Antonio Barberini to give up the effort for Cardinal Maculano. Cardinal Antonio wrote to the Marquis de Saint-Chamont while Maculano's campaign was still going on [Siri, p. 675]:

Hò participato con li Signori Cardinali Lione, e Theodoli il negotio circa il Signor Cardinale Pamphilio, e concorrono con la mia opinione di acconsentire alla sua elettione. Al Signore Cardinale Bichi non ne hò parlato perche lui si mostra troppo appassionato contra il Signor Cardinale Pamphilio.

But when the news got around the Conclave that the French Ambassador had advised his faction to drop Maculano, his campaign collapsed immediately.

On one of these days (Siri does not say which; though he reports it sequentially after the departure of Cardinal Mattei) a Scrutiny was held, in which Cardinal Cennini received 14 votes on the scrutiny and eleven more on the accessio, for a total of twenty-five [Siri, 676]. Cardinal Antonio Barberini was so indignant at the proceedings, so frustrated, so exasperated, that he fell ill, with symptoms of diarrhoea and vomiting, and there was talk of him leaving the Conclave or of his being in danger of death. Two things were crystal clear to him: a pope could not be made without his participation; and the prospects of Sacchetti were no longer viable [Siri, 655]. Also around this time, Mazarin's secretary, Alessandro Fabri, arrived in Rome, bringing a message to Barberini to maintain the exclusiva against Pamphilio, and a letter to all the rulers of Italy not to attempt to harm the Barberini by pressuring the new Pope against his family. It seems clear that the French Court did not yet have the dispatch containing Barberini's memorandum in favor of supporting Pamphili, or Saint-Chaumont's endorsement of it. Their reaction to those materials did not reach Rome until September 19, by which time it was too late to have any effect.

On the morning of Wednesday, September 14, Barberini sent Cardinal Facchinetti to Cardinal Albornoz, to propose a candidate who was acceptable to Spain—Cardinal Pamphilio; and to request the Spanish king to extend his protection to the family of Barberini, against any action the King of France might take against it. Albornoz gave the appropriate positive responses, and promised that he would speak with his faction immediately, indicating that on the next scrutiny the Spanish faction hoped to give him fifteen votes for Pamphilio. Barberini thereupon made his decision to bring about the election. He spoke to his brother, and sent Facchinetti and Rappaciolo to inform the cardinals who were on his list of supporters [Siri, p. 680]. That evening Cardinal Panciroli arranged a meeting between Pamphili and the Barberini brothers; and then they went publicly to call on Cardinal de' Medici in his cell. All then went to Cardinal Albornoz' cell, and from there they went to call on Cardinal Pamphilio and acquaint him with what was about to happen. Meanwhile, the French found out what was going on, and Bichi and Richelieu set out, without success, to stop the rush to Pamphili. Bichi accosted Antonio Barberini in the Sala Regia, and spent two hours, without success, to turn him back to the exclusiva against Pamphili.